EUGENICS AND DYING RACE THEORY: THE COLONIAL

advertisement

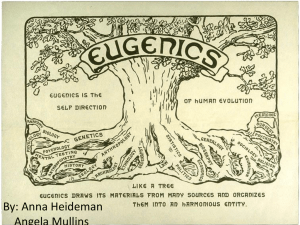

EUGENICS AND DYING RACE THEORY: THE COLONIAL PERSPECTIVE Philippa Levine, Department of History, LAS A: Area/Importance of Research I am beginning new research for a study of eugenics and dying race theory, with particular but not exclusive reference to the British Empire, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Eugenics (or the science of heritability, as it was often known in the early twentieth century) has a notorious history related not merely to the Nazi period in Germany, but to social policy in many western nations, including both the US and Canada. Curiously, there is almost nothing written about eugenics and imperialism despite its ascendancy at a time when the major European nations all boasted substantial colonial possessions. The archival record (with which I am familiar, having spent a decade studying imperial medical and policy records for a recently published book, Prostitution Race and Politics: Policing Venereal Disease in the British Empire [Routledge: New York, 2003]) suggests that colonists throughout the British Empire were deeply and often urgently interested in this topic, however. There was constant fear of racial dilution and of miscegenation, and a powerful belief that more ‘primitive’ races would die out under the conditions of modern life. There was, moreover, a considerable literature generated by scientists on the wisdom of using white labor in tropical conditions. These fears often took markedly different forms in various sectors of the empire; in Australia, the policy of ‘biological absorptionism’ attempted to breed ‘blackness’ out of the Aboriginal population, while in Fiji, the belief amongst planters that the indigenous population was doomed to extinction made the importation of allegedly sturdier indentured laborers from elsewhere (mostly South Asia) a particularly urgent priority. And while there is a considerable national literature on Australian eugenics, there is little else about the empire. Furthermore, that Australian body of work seldom yokes empire and eugenics in a way I see as critical to understanding these policies. Beliefs in genetic heritability and in racial typing were not merely popular prejudices, but were sustained by both contemporary scientific and anthropological knowledge. One of my main interests in using the highly racialized site of the British Empire as the canvas to study this issue to facilitate answers to the critical question of how and why ‘race’ moved from being considered a biological entity to being regarded as merely cultural, What were the changes in both the scientific community and in cultural practice that catalyzed such a broad change? It would be an ahistorical simplification to suggest that it was exposure to the war crimes committed in Germany in the 1940s that precipitated such a change. By the late 1930s many in the scientific and anthropological communities had already begun to repudiate both eugenics and dying race theory. I want to explore what motivated these significant shifts in scientific thinking, but also to connect backwards through dying race theory to trace the early history of eugenics. The most typical explanation of the origin of eugenics (beyond the coining of the term by Francis Galton in the 1880s) is via a Mendelian world view; I am keen to investigate what I believe to be the close and as yet largely unexplored connection of eugenics to an older but tenacious belief in dying races, observable in colonial North America, in Australia and New Zealand, in Fiji and elsewhere in the British Empire. B: Impact Philippa Levine 2 While this is a historically-oriented project, looking at eugenics and dying race theory c. 1850-1930, the key questions asked should have resonance for practitioners in a number of fields. They are, moreover, questions which I would contend cannot be satisfactorily tackled other than through interdisciplinary conversations and explorations. In particular, this project will make concrete connections between genetics and biology and my own discipline of history, Eugenics, although now largely abandoned by scientists and medical researchers, is nonetheless an important forerunner of contemporary genetics. Exploring the shifts in emphasis as well as changing scientific practices that have taken genetics in significantly new directions will allow scientists to appreciate the opportunities and ramifications of their studies in a broader context. For the historian locating these practices scientifically marks something of a departure from a more usual emphasis on culture and social structure, and will ensure a better level of understanding between the two disciplines. Since both the earlier practice of eugenics and today’s human genetics projects are widely recognized as having substantial social and bioethical consequences, a study sited at the intersection of science and social policy, as this is, will learn from and I hope speak also to ethicists, law/policy makers, and medical anthropologists. C: Outline of Work Plan My plan for the year would be twofold: to immerse myself in the literature of eugenics, and to become familiar with the scientific issues that connect eugenics and contemporary genetics so that I might better understand the practice of science. My earlier work in medical history has given me a fair grounding in the philosophy and history of science (Lakatos, Feyerabend, Latour, et al): my intent here is to take Philippa Levine 3 advantage of USC’s particular and impressive expertise in the field of genetics and to learn ‘in the field’ and from the practitioners. Eugenics spawned a huge and multinational written record, mostly in the form of learned journals devoted to the field. I have some but insufficient knowledge of this literature and would plan to spend a good deal of time working through the primary printer materials which are readily available. The interest of former USC President Von Kleinsmidt in eugenics also makes USC a good environment in which to begin this project. I would also plan to travel out of Los Angeles on occasion (and out of term time) to check on archival leads as I encountered them; I am confident that the New York and Philadelphia libraries of medicine may yield some otherwise unobtainable materials alongside the London archives. D: Expected Product My intent would be to have a sufficient grasp of the material and the topic at year’s end to seek major funding (probably from NSF or NIH, from whom I have received funding in the past) for completion of the project. I would also envisage having an article or two ready to submit to journals. The ultimate aim of the project is a booklength monograph, but this is still some way off. E: Key Faculty Ronald Garet Law School Ethics Brian Henderson Keck School of Medicine Genetics Cheryl Mattingly Anthropology/Occupational Health Anthropology David Sloane SPPD Policy/Planning Michael Waterman Computational Biology Molecular/Comp. Biology Philippa Levine 4