THE AUSTRALIAN PLANT PEST DATABASE

advertisement

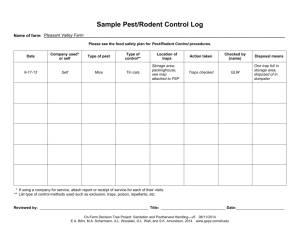

THE AUSTRALIAN PLANT PEST DATABASE Dr Ian Naumann SPSCBP Program Director Office of the Chief Plant Protection Officer Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry INTRODUCTION In addition to looking after the collection and providing taxonomic support to quarantine services and agricultural industries, taxonomists increasingly need to be proficient in the use of electronic databases to manage disease records and other data held in the collection. Many curators regard access to computer indexing or databasing systems as a priority. Specialised information technology systems are available which facilitate the convenient and rapid location of specimens and disease records held in collections. The software needed for this task is relatively inexpensive, however there needs to be an ongoing commitment from the relevant institutions to allocate resources for data entry. Another major consideration in the development of any database is the quality and quantity of the underlying information. In many institutions, a significant amount of work is required in the taxonomic area, both in validating existing records and clearing a backlog of unidentified specimens. It is also important that countries establish minimum data standards for their pest records to ensure that they can meet the international standard set out under ISPM No. 8. The following Section provides an example of one approach for managing disease records. It describes the Australian Plant Pest Database (APPD), which utilises distributed database technology to link diverse, geographically isolated databases so that all of the available data can be accessed from a single point. In a sense, the technology creates a single, virtual national (or regional) database that can be maintained and regularly updated at the local level. Located on the Internet, the APPD provides a gateway to information existing in many different Australian databases. PLANT HEALTH AND DISTRIBUTED DATABASES The APPD provides the plant health scientist with convenient and quick access to information by drawing on pest records residing in over 20 geographically isolated collection databases (Figure 1). The records hold information on: current scientific and common name, taxonomy, collection locality (including geo-coding), collection date, collector name, collection accession number and host plant. The database can be queried dynamically, by using more than one field, for example, by host plant and geographic locality. The distributed database is also able to consolidate pest record information across agencies, allowing a national perspective on the status of a particular pest, and record verification. The APPD is a plant health tool, which can be used for agricultural trade, emergency exotic and endemic pest management. Similar distributed database systems have been developed elsewhere using different technology, according to user needs and data structure. It is anticipated that many of these biologically based distributed databases will eventually reside within the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) infrastructure. Figure 1: How the APPD works ESSENTIAL ELEMENTS FOR SUCCESS OF THE APPD Solutions to the following challenges have been critical to the implementation and value of the Australian Plant Pest Database. 1. Funding Following from the 1995 Nairn review of quarantine, and recommendation of the development of a national pest and disease system, Commonwealth Budget Initiative funding was provided for the development of the APPD. The funding was facilitated through Plant Health Australia (PHA), with a small proportion overall for the design of the distributed database software (see 2. Heterogenous systems), and the majority as seed money to initiate databasing activities within pest collections. Substantial in-kind contributions were provided to the APPD network by agencies who were custodians of the collections, in the form of taxonomic expertise, staff and equipment. 2. Heterogenous systems Australian plant pest collections are heterogenous in the way information is stored within local databases (e.g. locality data may occupy a single, or several fields), and the means by which the information is stored (different database packages, such as Microsoft Access, BioLink or Texpress). “Wrapping” software designed by CSIRO Mathematics and Information Sciences (CMIS), overcame these local differences, allowing the central “broker” software (Figure 1) to recognise the differently formatted information, and then to translate it into a homogenous, consolidated report for the user. 3. Management A Steering Committee was formed to oversee the development, population and implementation of the APPD. This included the guidelines for all APPD stakeholders in the APPD Rules of Operation. The Rules of Operation addresses data sharing, security, record standards, data reliability, agency commitment and access issues. Membership of the Steering Committee consists of curators, collection and plant health agency representatives, with the OCPPO as secretariat. 4. Priorities A streamlined approach towards datacapture was established, so that the benefits of the APPD would prevail in the immediate future. Select pest groups were chosen based on their significance as plant pests and well-defined pest taxonomy. Priority taxa included taxa from fungal, arthropod and nematode groups. Some additional (non-priority) taxa were permitted for datacapture, on a case-by-case basis. Support was given to Australian Biological Resources Study (ABRS, Environment Australia) towards the development name lists of mutual interest. This assisted the dissemination of important pest taxonomy data that may be less accessible through written publications. APPD OUTPUTS Easy access to important plant pest records held in around 20 Australian collections; 1,000,000 plant pathogen, arthropod and nematode records by mid 2004; A unique, cross institutional partnership of taxonomic specialists, collection curators, plant health scientists, industry, State and Commonwealth government scientists and policy makers; A model to other countries and regions aiming to establish similar virtual collections. EXAMPLES OF APPD BENEFITS Case study 1: Support of trade decisions AFFA makes extensive use of the APPD to underpin its negotiations with other countries when Australian industries are seeking access to new markets. Guignardia citricarpa, is a debilitating bacterial disease of citrus also cosmetically damaging to fruit. Its status is considered quarantinable. By mapping locality data of the disease against commercial citrus areas of Australia (Figure 2), it is revealed that the disease has not been recorded in citrus exporting areas of Australia, and thus supports Australia’s overseas market access bid based on area freedom. Figure 2: Guignardia citricarpa area of freedom in Australia Case study 2: Pest biology By amalgamating information from various collections, the APPD can provide useful information for endemic pest incursion management. The APPD can provide a national picture of pest biology for a given species, and this information can then be used to predict future, local scale incursions and potential host plants or alternate hosts (“refugia”) that may assist in distributing a local scale incursion. Pest record data also provides a primary information source to specialists, contributing to existing pest knowledge from available literature. The APPD facilitates information exchange as scientists can identify previously unknown information by remotely accessing individual collections and using different parameters to search multiple records. For example, Helicoverpa armigera and the related H. punctigera are responsible for $A200 million in annual damage in control costs in cotton alone. A search of the APPD reveals, for example: Whether regional differences in seasonality or host preference exist; and Which alternate host plants might serve as “refugia” in managing resistance to transgenic cotton. Case study 3: Emergency response The APPD may also be used to develop responses to suspected invasions of exotic pests. For example, in 2002, a new record of an apple disease Alternaria mali was notified to the OCPPO. New taxonomic information had indicated that the disease may have been recorded as A. alternata and Alternaria sp. The Office of the Chief Plant Protection Officer searched the APPD fungal and host records, analysed symptom information and was able to determine that A. mali was already established in Australia. The Plant Health Committee then agreed not to proceed with further emergency response.