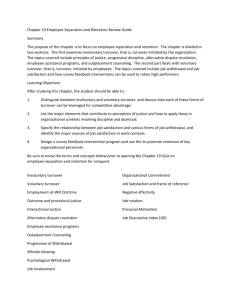

Meier_diversity

advertisement

AUTHOR: Kenneth J. Meier Sharon H. Mastracci Kristin Wilson TITLE: Gender and Emotional Labor in Public Organizations: An Empirical Examination of the Link to Performance SOURCE: Public Administration Review (Washington, D.C.) 66 no6 899-909 N/D 2006 COPYRIGHT: The magazine publisher is the copyright holder of this article and it is reproduced with permission. Further reproduction of this article in violation of the copyright is prohibited. To contact the publisher: http://www.aspanet.org ABSTRACT Scholars of public organizations have begun to emphasize emotional labor in studies of gender in the workplace, finding that the skills women bring to organizations are often overlooked and under compensated even though they play a vital role in the organization. Emotional labor is an individuals effort to present emotions in a way that is desired by the organization. The authors hypothesize that employers with greater emotional labor expectations of their employees will have more effective interactions with clients, better internal relationships, and superior program performance. This article tests the effects of emotional labor in a bureaucratic workforce over time. Multiple regression results show that organizations with more women at the street level have higher overall organizational performance. Additionally, emotional labor contributes to organizational productivity over and above its role in employee turnover and client satisfaction. Essays on Equity, Gender, and Diversity In a 2004 Public Administration Review article, Mary Ellen Guy and Meredith A. Newman introduced the concept of "emotional labor" to public organizations. Emotional labor consists of personal interactions--separate from actual job descriptions-- among employees and between employees and clientele that facilitate the effective and smooth operation of the organization. As Morris and Feldman define it, emotional labor is "the effort, planning, and control needed to express organizationally desired emotion during interpersonal transactions" (1996, 987). Guy and Newman demonstrate that the employees who are most likely to be required to provide emotional labor in an organization are women and that organizations generally undervalue emotional labor, resulting in lower salaries paid to women compared to men. Similarly, Webb (2001) and Bellas (1999) have found that female public servants are expected and required to engage in emotion work to a greater degree than men, and the typical employee responds to occupational expectations in the same manner that she aspires to meet explicit requirements articulated in a job description. Finally, Hochschild (1979) identifies both gender- and class-based associations with on-the-job emotional labor expectations. This paper starts by accepting the idea that women employees are more likely to contribute emotional labor to the organization and asks whether we can empirically demonstrate results that are consistent with this idea. Though such an assumption is not without debate, we discuss theoretical foundations that allow for it, particularly in an undertheorized area of inquiry. This approach is designed to supplement more qualitative approaches to the same question. First, a brief review of the emotional labor literature will provide some theoretical specification of the concept and how it might affect organizational performance. Second, we design an empirical test of this theory using a large sample of school districts to examine measures of client satisfaction, employee satisfaction, and overall organizational performance. Third, we present empirical findings that are consistent with the idea that emotional labor is an important part of organizations and their performance. Finally, we conclude by addressing a set of normative and empirical issues raised by the literature and the results of this paper. Emotional Labor as a Concept Weber's (1946) ideal typical bureaucracy eliminated the personal, informal aspects of the organization to create a rational, impersonal bureaucracy. Scholars have long known that the formal and impersonal side of bureaucracy is supplemented by a human side that encompasses values, norms, mores, and personal attributes (Barnard 1938; Follett 1940; McGregor 1960; Simon 1947). Starting with Hochschild (1979, 1983) a group of scholars distinguished emotional labor from these informal aspects of organization. Emotional labor is the projection of feelings and emotions needed to gain the cooperation of clients or coworkers, the ability to see another's side of the issue and integrate that perspective into what the organization does. Akin to other work-related skills, employee emotions are subject to management in order to realize an employer's objectives. According to Guy and Newman, these are the emotions that are "a mainstay of health and human service professions, public education, paraprofessional jobs, and most support positions such as administrative assistants, receptionists, clerical staff and secretaries" (2004, 289). These processes, with rare exception (Steinberg 1999), are not part of the formal job description, with its focus on measurable skills, achievement levels, or attributes. Therefore, according to Guy and Newman, emotional labor is generally undervalued in organizations, resulting in lower pay for persons in positions that call for emotional labor. Although this can explain an aspect of the gender pay gap, as Guy and Newman point out, it "begs the question: What is it about women's jobs that causes them to pay less?" (2004, 289). Both Fletcher (1999) and Guy and Newman (2004) contend that scientific management and similar approaches squeezed out the consideration of emotional labor because it is difficult to measure and does not fit in with standards of how organizations should operate. Workers in an organization are defined by positions, and the logic of position classification is that two similar positions (or the workers who fill those positions) are equal substitutes for each other. Although Tilly and Tilly (1994) examine skill sets in general, but not emotional labor specifically, differences between women's and men's capacities to engage in emotion work indicate that they may not be ideal substitutes for each other.(FN1) One attempt to reconcile emotional labor with scientific management approaches is Goleman's (1998) concept of "emotional intelligence." Emotion in an organization can clearly have negative as well as positive consequences for the organization (see also Sass 2000; Shuler and Sypher 2000; Wharton 1993). Employees might "go native" and help clients subvert the system, or interpersonal ties might result in cliques rather than informal methods of getting work done. Emotional intelligence, in Goleman's view, is the management of emotional labor so that it benefits the organization. The few studies of emotional labor in the private sector have generally involved qualitative examinations of specific sectors, such as air travel, retail sales, emergency response, or health care delivery. Some case study evidence indicates that emotional labor can affect organizational performance. Pugh (2001), examining the retail banking industry, found that greater emotional labor had a positive impact on customers, resulting in customer loyalty, repeat business, and financial gains for the bank. Sass (2000) and Shuler and Sypher (2000) show positive results for nursing home workers and 911 dispatchers, respectively. Nursing in particular has been the subject of several studies (James 1989; O'Brien 1994; Smith 1998; Steinberg 1999; Steinberg and Figart 1999). Sometimes the targets of emotional labor are not clients but other members of the organization. Pierce (1999) shows how paralegals were able to support and maintain the emotional stability of the lawyers for whom they worked through deferential treatment and caretaking. Emotional labor can also be part of an organization's values and norms. Sutton's (1991) study of bill-collection agencies argues that managers who understand emotional labor can provide a better work environment for employees. In part, this work environment might be more congenial because workers can express their emotions, thus allowing for greater commitment to the organization and its objectives. Although emotional labor is not necessarily gender specific (Goleman 1998), the overwhelming majority of studies show that women both provide more emotional labor and are subject to expectations that they will do so (Bellas 1999; Hochschild 1979, 1983; James 1989; Martin 1999; Pierce 1999; Webb 2001). This is akin to gendered differences in family care responsibilities: Although no physiological justification exists for one sex or the other to assume such duties, particularly elder care, women provide and are expected to provide the bulk of family care. Hochschild has revealed and articulated the gendered dimensions of both emotional labor (1979, 1983) and family care (1997), finding that women not only provide the bulk of both but also are expected to do so. To proceed with analyses of family care responsibilities or emotional labor provision as if such highly institutionalized behaviors and expectations did not exist is not useful, in our view. Thus, Martin's (1999) study of police officers is especially relevant because women police officers were expected to provide emotional labor within the organization through "informal interaction with other officers," in contrast to interactions with citizens, where both male and female officers were expected to provide emotional labor. Much of the gender segregation by occupation has links to emotional labor because many femaledominated occupations are expected to employ emotional skills to bring about organizational ends, whereas male-dominated occupations are not. Much of the gender segregation by occupation has links to emotional labor because many femaledominated occupation are expected to employ emotional skills to bring about organizational ends, whereas male-dominated occupations are not. The gendered nature of emotional labor is perhaps best revealed by feminist theories of bureaucracy. In the work of Ferguson (1984), Stivers (1995, 2002), and others, the traits associated with emotional labor--capacity for employing emotions as a skill to achieve organizational mission, willingness to listen, ability to see other sides of an issue, a concern with personal relationships, the nurturing others--are the traits bureaucracies seek to eliminate, reduce, or at least undervalue. Stivers, in particular, seeks an explicit recognition of these feminine roles and a restructuring of bureaucracy to accommodate them.(FN2) From a somewhat different perspective, one can seek elements of emotional labor or the importance of emotional labor in some management theories. The stress on informal aspects of organizations in the human relations approach is fairly self-evident (Argyris 1964; McGregor 1960). Less self-evident but equally supportive is the emphasis on values as central to organizations and building loyalty within the organization (Barnard 1938; Simon 1947). More recently, even the New Public Management, an approach that ostensibly takes efficiency as its preeminent value, has a "citizens as customers" orientation (Dilulio, Garvey, and Kettl 1993; Osborne and Gaebler 1992). If agencies see themselves as providing services to customers, then emotional labor becomes an integral part of the process of gaining consumer support and loyalty. The literature on emotional labor provides a challenging set of ideas concerning organizations and research on organizations. This study seeks to add a new dimension to studies of emotional labor. We ask the question, if emotional labor exists and if it is primarily associated with women employees, how do organizations differ? How would this generate evidence of better relationships with clients or better relationships among employees? How might either of these differences be tied to what organizations can accomplish? The Empirical Study Virtually all studies of emotional labor are either theoretical or qualitative case studies (an exception is Guy and Newman, who use the concept as a basis for explaining gender differences in salaries; see also Mastracci, Newman, and Guy 2004). One of the reasons for this methodological choice is that emotional labor can be documented only by observing interactions between one person and another (either another employee or an organization's client). Documenting emotional labor in large-scale studies, as a result, is difficult, if not impossible. This study takes a different approach: It assumes that women are the preponderant suppliers of emotional labor and then looks at whether the other implications of emotional labor appear in organizations that employ a larger proportion of women. Again, one might charge that the assumption that emotional labor is gauged by the proportion of women in an organization is essentialist. However, this initial attempt to estimate emotional labor and to link it to organizational performance not only calls attention to the importance of emotional labor as a factor in performance but also the need for better measures. Although it is an imperfect and perhaps unfair proxy for emotional labor, our operating assumption is supported by the literature. Guy and Newman list several examples of "the conflation of gender and emotional labor" (2004, 293-94), and Glomb, Kammeyer-Mueller, and Rotundo (2002) have found a statistically significant link between emotional labor demands in an occupation and lower wages. Notably, low-wage occupations are consistently female dominated (Mastracci 2003). In short, if the assumption that women supply most of the emotional labor to an organization is true, how else might these organizations be different in predictable ways? Theoretical Hypothesis 1: Organizations with more emotional labor will have more positive interactions with clients (Guy and Newman 2004, 295). This hypothesis is the central theoretical argument concerning emotional labor. As employees bring more emotional labor to their interactions with clients, clients will be more satisfied with these interactions and engage in behavior that facilitates organizational performance. This behavior might be as simple as showing up at the organization for treatment, or it might consist of relatively elaborate behaviors, such as those called for in the coproduction of mental health or education services. Theoretical Hypothesis 2: In organizations with more emotional labor, relationships within the organization should be better. Emotional labor provides the glue that holds organizations together. Theoretically, it makes the organization a more pleasant place to work; it might even provide significant job satisfaction to individuals who provide that labor. One implication of this greater satisfaction, then, is that these organizations will experience fewer personnel problems (Guy and Newman 2004, 292). We are not assuming, however, that only one type of emotion--niceness, politeness, or caring-necessarily brings about positive organizational outcomes. Assertiveness and the creation of an environment in which individuals feel free to state their needs plainly and confront even sensitive issues openly can also bring about positive organizational outcomes. We hypothesize that a greater proportion of women--who have been found not only to provide emotional labor but also are expected to do so (Bellas 1999; Guy and Newman 2004; Hochschild 1983)--will engender such an environment and will enable the capacity for emotional work necessary to bring that about. All else being equal (labor pool characteristics, agency missions, etc.), such organizations might have lower turnover rates than similar organizations. Testing this hypothesis and others requires a set of organizations that perform the same function. Theoretical Hypothesis 3: Organizations with more emotional labor will be more effective than other organizations, all else being equal The bottom-line argument for emotional labor is that it improves organizational performance. One argument flows directly from hypotheses 1 and 2. High levels of organizational turnover require organizations to invest more funds in the recruitment and training of workers. New workers face a learning curve whereby they get better at their jobs as they become more familiar with organizational expectations. Lower turnover, therefore, should lead to more organizational effectiveness. Similarly, more cooperative clients who are willing to assist rather than resist the organization should make the attainment of organizational goals easier. Whether these are the only two ways that emotional labor facilitates organizational effectiveness is open to question, however, simply because emotional labor might also influence other organizational processes (e.g., team building, more open accountability processes). Any empirical test should determine whether emotional labor has an impact on performance over and above its impact on turnover and client behavior. The Empirical Setting: School Districts Schools are ideal settings in which to examine the influence of emotional labor. Several scholars specifically mention teaching as a job that has an emotional labor component (Bellas 1999; Guy and Newman 2004; Hargreaves 1995; James 1989; Nias 1996). Education requires teachers to interact on several levels with students in order to motivate them to learn. The educational literature is in unanimous agreement that although classroom instruction is important, what students do at home is also critical. Education, in short, is a classic coproduced good that requires the cooperation of the student and the student's family. The study of schools as organizations is facilitated by the existence of large data sets documenting everything from student performance down to the minute details of educational finance. These extensive databases mean that studies of schools or school districts as organizations do not have to start from square one but have both a good database and an extensive literature that suggests how processes work. This study examines the universe of Texas school districts during three academic years (2000-02). In addition to having an excellent database that has been used to study other important questions about public organizations (Bohte 2001; Smith and GranbergRademacker 2003; Smith and Larimer 2004; Weiher 2000), Texas has the advantage of being home to more than 1,000 of the 14,000 school districts in the United States. These districts range from rural to urban, rich to poor, small to large, and homogeneous to heterogeneous. In short, as educational organizations go, they are highly diverse. The findings from this study, therefore, can likely be generalized to other public school systems. Whether they can be generalized to other public organizations is an open question. Although public schools are the most common public organizations in the United States and employ far more public servants than any other type of governmental organization, schools are highly professionalized organizations that vest a great deal of discretion at the street level (i.e., the classroom). The findings here most likely apply to similar types of organizations, but only additional empirical studies can verify that contention. Key Variables and Research Hypotheses The four key theoretical variables in this study are emotional labor, client satisfaction, employee satisfaction, and organizational performance. As noted previously, we assume that emotional labor can be measured by the percentage of female employees and that organizations with more female employees will generate more emotional labor, all else being equal. In this study, we use the percentage of teachers who are female. Education is a policy area that is characterized by glass ceilings: Although teachers are overwhelming female, as one moves up the hierarchy, only 8 percent of superintendents are women (Meier and Wilkins 2002). The average district in this study had 75.4 percent female teachers, but the range is substantial, from 38.9 percent to 100 percent. Though client satisfaction might be measured in a variety of ways (and we could debate whether schoolchildren, their parents, or others in the community are the clients), this study uses student attendance. We assume that emotional labor makes the educational experience more pleasant for students. Although much of absenteeism is unavoidable because of illness or other factors, a portion of it is linked to student motivation. Particularly among older students, positive experiences in school are associated with higher attendance (Phillips 1997). The measure is the average daily attendance percentage, which ranges from 91.4 percent to 99.2 percent. H[sub1]: The percentage of female teachers will be positively associated with average daily attendance. As noted earlier, employee satisfaction will be measured by employee turnover--in this case, teacher turnover. Compared to most other public employees, teacher turnover is high. The average district had 16.9 percent of its teachers leave in a year; again, the range is substantial, from 0 percent to 100 percent (in the latter case, a school district with three teachers had all leave in the same year). H[sub2]: School districts with higher percentages of female teachers will have lower teacher turnover rates. Four measures of organizational outcomes are used to assess the effectiveness of these school districts. Clearly, the most salient outcome measure for Texas schools is their overall pass rate on the state standardized test (known during 2000-02 as the Texas Assessment of Academic Skills, or TAAS). The TAAS is a high-stakes test that students must pass in order to graduate from high school; schools and school districts are evaluated based on the TAAS, and those evaluations are front-page news when released. The mean pass rate for the TAAS was 84.5 percent, with a range of 32 percent to 100 percent. The TAAS is a mid-level achievement indicator, picking up basic skills. A full assessment of performance would also look at indicators that are more sensitive to at-risk students and those that reflect the performance of the district's best students. For at-risk students, we will use the dropout rate, measured as the total percentage of students who drop out of school in grades 9-12 (mean = 5.2 percent, range = 0 percent to 37.5 percent). Although they are widely criticized as underestimating the true dropout rate, the official figures provide a rough gauge of performance failure for at-risk students. For collegebound students, we use the average ACT score (Texas institutions of higher education require the ACT; mean= 19.9, range = 12.2 to 26.7) and the percentage of students who scored above 1110 on the SAT or its ACT equivalent (a state-defined measure of college readiness; mean = 20.9 percent, range = 0 percent to 75 percent). H[sub3]: The percentage of female teachers will be positively associated with TAAS scores, ACT scores, and the percentage of students scoring above 1110 on the SAT and negatively associated with dropouts. Control Variables A variety of other factors affect attendance, turnover, and organizational performance, so a series of control variables must be included in each regression. Because class attendance can be considered similar to an organizational performance indicator (although it is an output rather than an outcome), it can be estimated with the same set of controls as the other outcome measures. In the field of education, a well-developed set of educational production functions exist that specify the types of variables that should be used as controls (Hanushek 1996; Hedges and Greenwald 1996). Essentially, these control variables can be grouped into two sets: resources and constraints. As indicators of resources, we include per-student spending on instruction, average teacher salary, class size, average years of teacher experience, and the percentage of noncertified teachers. As constraints on performance, we include the percentages of black, Latino, and poor students, the latter being defined as students who are eligible for free or reduced-price school lunches. Teacher turnover is a different phenomenon from organizational performance, and therefore, it is likely affected by different factors. We generally expect that incentives, the difficulty of the job, and organizational support factors play a role in personnel turnover (Griffeth, Hom, and Gaertner 2000). To tap incentives, we include both the average teacher salary and the median income of all persons living in the school district (in combination, these contrast non-teaching opportunities with teaching remuneration). Task difficulty is measured in the same way as constraints in the production function--the percentages of black, Latino, and poor students. Organizational support factors include class size, the ratio of teacher aides to students, and the number of administrative staff per 100 students. Because new teachers are more likely to leave the profession, the percentage of teachers with five or fewer years of experience is included. Finally, because student performance might make the job more attractive to teachers, we include the TAAS pass rate from the previous year in the equation. In both cases, the objective is not to provide a complete explanation of the dependent variables--that is a question of concern for education policy, not public administration. Rather, the objective is to include sufficient controls so that we can be confident the results are not spurious. Because we have several indicators of a given concept, such as resources, the equations are characterized by a fair amount of collinearity in these variables. As a result, the individual resource coefficients sometimes become negative in the presence of controls for other resources. Finally, each of the equations includes dummy variables for the years 2001 and 2002 to control for any serial correlation in the data. Findings If our theoretical assumption is correct and emotional labor is provided primarily by female employees, we should see a positive correlation between female teachers and student attendance. Although many attendance patterns are not systematic, simply because illnesses cannot be predicted in advance (see table 1), the regression results show a positive relationship between the percentage of female teachers and student attendance. A 1 percentage point increase in female teachers is associated with a 0.0102 percentage point increase in class attendance, all else being equal. The relationship is not large, but over the full range of the data, female teachers make a 0.63 percentage point difference-about 8.1 percent of the current range-- in attendance. Relatively small differences such as this, when spread out over the 4.2 million students in Texas, could have a substantial impact.(FN3) Our first hypothesis is supported by the data. The remaining significant relationships in the table are consistent with our expectations: Lower attendance is associated with black students, poor students, larger classes, and uncertified teachers. Table 1 Emotional Labor and Client Satisfaction: The Relationship between Female Employment and Attendance Dependent Variable = Daily Class Attendance (Percent) Independent Variable Slope T-score Female teachers (percent) .0102 5.24 Teachers salaries (thousands) -.0046 0.56 Instructional funding (thousands) -.0186 0.93 Black students (percent) -.0065 4.71 Latino students (percent) .0009 1.02 Low-income students (percent) -.0103 8.34 Class size -.1275 12.28 Teacher experience .0087 1.17 Noncertified teachers -.0131 4.83 R[sup2] .20 Standard error .74 F 70.63 N 3,118 Note: Coefficients for individual years are not reported. Do the positive benefits of emotional labor also accrue to employees of the organization? We hypothesized that because greater emotional labor would generate more satisfaction with the job, it would reduce turnover. Because turnover varies a great deal by type of organization and by profession, having a large number of organizations that perform the same function-- education--is useful. Table 2 shows that a 1 percentage point increase in female teachers is associated with a 0.12 percentage point decline in teacher turnover, all else being equal. Over the full range of the data, this translates into a maximum reduction in teacher turnover of about 7.5 percentage points, almost a full standard deviation in turnover rates (or approximately 21,000 teachers per year). With a few exceptions, turnover is negatively related to low-income students and positively associated with more teacher aides; the remaining relationships in table 2 are consistent with the expectations in the literature. Increased student attendance and lower teacher turnover are intermediate processes in the education system. What is more important is the knowledge learned by the student. Do greater attendance and lower teacher turnover translate into higher achievement levels? Table 3 presents three different views of the relationship of emotional labor to student performance on the TAAS. The first column uses the percentage of female teachers as the sole indicator of emotional labor. A 1 percentage point increase in female teachers is associated with a 0.0746 percentage point increase in the number of students passing the TAAS, all else being equal. Over the full range of the data, this translates to a maximum impact of about 4.5 points on the TAAS, a little over one-half of a standard deviation in test results. All other relationships in the first column are consistent with the findings in the literature, except for instructional funding. Instructional funding is fairly collinear with the other variables in the model, sharing 70 percent of its variance with other independent variables, notably, teacher salaries and class size (which, in combination, make up most of instructional funding). The high level of collinearity changes this sign from positive to negative. Table 2 Emotional Labor and Employee Satisfaction: The Relationship between Female Employment and Turnover Dependent Variable = Teacher Turnover (Percent) Independent Variable Slope T-score Female teachers (percent) -.1214 6.39 Teachers salaries (thousands) -.5007 6.27 Median income (thousands) .0374 2.03 Black students (percent) .0458 3.32 Latino students (percent) .0050 0.56 Low-income students (percent) -.0285 2.06 Class size .0166 0.22 Less than five years experience .2076 14.20 Teachers aides .0718 2.49 Total bureaucracy 1.8591 6.69 TAAS pass rate (t-1) -.1332 7.03 R[sup2] .23 Standard error 7.24 F 72.83 N 3,111 Note: Coefficients for individual years are not reported. The second column of table 3 adds student attendance and teacher turnover directly into the model. The estimation is designed to tell us whether the full impact of female teachers (the surrogate variable for emotional labor) operates through improved student attendance and lower teacher turnover or whether female teachers have an impact over and above the influence of these two processes. The second column shows that student attendance and teacher turnover have strong relationships in the predicted direction with student performance. Although the impact of female teachers is reduced by about onehalf, it remains a strong positive influence on student performance. In short, if we are correct in our assumption about emotional labor, it influences student performance both directly and indirectly by improving student attendance and by lowering teacher turnover. The final column of table 3 specifies a stringent test of our emotional labor hypothesis by including a lagged dependent variable. Such a specification requires our independent variables to influence student performance over and above any influence the variables might have had in past years. This specification does reduce the direct impact of female teachers to zero, but the influence of both attendance and teacher turnover remain significant in the predicted direction. Even with the stringent autoregressive estimation in the last column, our third empirical hypothesis is supported. Table 3 Emotional Labor and Organizational Performance: Female Employment and Student Test Scores Dependent Variable = Percent Passing the TAAS Independent Variable Slope Slope Slope Female teachers (percent) .0746 (4.54) .0362(2.31) .0088 (0.79) Attendance rate --2.4390(16.97) .5216 (4.86) Teacher turnover rate ---.1146(7.71) -.0442 (4.17) Lagged TASS pass rate ----.6619 (55.63) Teachers salaries (thousands) .7438(10.64) .6877(10.27) .2307 (4.80) Instructional funding (thousands) -1.1022(5.43) -1.0387(5.40) -.2481 (1.80) Black students (percent) -.1894(16.19) -.1624(14.51) -.0458 (5.60) Latino students (percent) -.0666(8.63) -.0657(8.98) -.0186 (3.55) Low-income students (percent) -.1193(11.43) -.0977(9.76) -.0296 (4.12) Class size -.6641(6.99) -.3681(4.03) -.1544 (2.38) Teacher experience .1673(2.65) .0466(0.76) -.0243 (0.56) Noncertified teachers -.0940(4.10) -.0382(1.74) -.0083 (0.53) R[sup2] .41 .47 .73 Standard error 6.45 6.10 4.31 F 192.24 210.36 611.26 N 3,117 3,117 3,116 Note: Coefficients for individual years are not reported. Table 4 extends the analysis to three other educational outcomes--dropouts, ACT scores, and high scores on the college boards. In all three cases, the percentage of female teachers is associated with more positive outcomes for students (dropouts are a negative factor, so the relationship should be negative). The direct impacts of female teachers are supplemented by indirect impacts through improved student attendance in all three cases. The teacher turnover rate, however, has no influence at all on any of these three student outcome measures. Conclusion This article has investigated the concept of emotional labor in educational organizations. Our strategy was to assume that emotional labor existed and that women would be more likely than men to provide it. Based on that assumption, three empirical hypotheses were tested using Texas educational data. We found that organizations with more women at the street level--in the classroom--were also characterized by higher student attendance, lower teacher turnover, and higher overall organizational performance. The performance equations suggest that emotional labor contributes to organizational productivity over and above its contribution to employee turnover and client satisfaction. Although we did not measure emotional labor directly (in fact, it is unclear how one might do so in a large-scale study), the concept of emotional labor provided a plausible causal theory as to why the relationships we found were likely (Lynn, Heinrich, and Hill 2001). By facilitating cordial relationships among teachers and by enticing students to enjoy the education process, emotional labor should reduce turnover and improve client relationships. As befitting the first study of its type, the analysis raises more questions than it answers. Some of these questions are empirical, others are normative. Table 4 Emotional Labor and Organizational Performance: Female Employment and Other Performance Indicators Dependent Variables Independent Variable Dropouts College percent Female teachers (percent) -.0256 (1.82) (8.36) .2938 (8.35) Attendance rate -1.5974 (14.86) (3.92) 1.0716 (3.93) Teacher turnover rate -.0144 (1.18) (0.39) .0135 (0.17) Teachers salaries (thousands) -.0807 (1.60) (5.06) .7746 (6.30) Instructional funding (thousands) .0005 (0.00) (1.95) -.6891 (1.71) Black students (percent) .0375 (4.62) (7.13) .0245 (123) Latino students (percent) .0179 (3.27) (4.91) .0279 (2.06) Low-income students (percent) .0409 (5.31) (13.70) -.2889 (15.02) Class size .2141 (3.00) (1.20) -.1147 (0.64) ACT .0398 .1405 .0016 .0818 -.1054 -.0189 -.0088 -.0349 -.0282 Teacher experience .0606 (1.32) (1.20) .0916 (0.81) Noncertified teachers .0148 (0.91) (2.24) -.1364 (3.36) R[sup2] .23 .31 Standard error 4.19 9.97 F 66.37 94.77 N 2,897 2,785 Note: Coefficients for individual years are not reported. .0179 -.0175 .41 1.26 141.25 2,610 Guy and Newman (2004, 296) conclude their essay with the statement, "Making emotional labor visible is the first step; making it compensable is the next." Although this study did not address how emotional labor might be compensated, by linking emotional labor to organizational outcomes, it implies one way that organizations could monetarize the contribution of emotional labor. The link to performance provides an objective way of placing an organizational price on emotional labor: by directly linking pay to performance. At the same time, such a strategy is unlikely in these organizations, for several reasons. First, though linking pay to performance has generated some controversy in many organizations, it is particularly controversial in education, with strong opposition from teachers' unions. Pay-for-performance proposals in education are viewed by many as an effort to reduce all of education to a narrow set of economic values (Smith 2003). Second, pay structures in U.S. education are set up in a gender-neutral process by which every teacher with the same education and years of experience is paid the same salary (with a few modest exceptions for scarce specializations, such as math or bilingual education). Under this system, it is simply not possible to pay a woman less for filling the same role as a man.(FN4) Given that all personnel systems with discretion appear to create gender inequities, restoring discretion to the educational personnel process through a pay-for-performance system may not be an advantage for women. Third, moving to monetarize emotional labor by linking pay to performance might create incentives for behaviors that then undercut the benefits of emotional labor. Incentive systems are known to create self-interested behavior that maximizes one's own income at the expense of others (Blau 1956). Such actions might dissuade employees from providing emotional labor to their colleagues. Second, are there aspects of emotional labor that are their own reward? All incentive systems distinguish between monetary incentives and normative incentives, such as the value of work, the benefits of associating with colleagues, and similar nonutilitarian rewards (Etzioni 1964; Wilson 1989). Any set of conversations with individuals in the helping professions (teaching, nursing, social work) will reveal that self-selection biases operate. Individuals choose such professions precisely because they provide an opportunity for normative rewards, one of which might be the use of emotional labor. If emotional labor is self-fulfilling, are their risks inherent in trying to monetarize it? Webb observed increased dissension and resistance within one state-level government office when attempts were made to elevate emotion work to a skill in job descriptions and performance evaluations: "change is resisted because the employers' aim is to consolidate the bonus element into normal pay, which would result, at least in the short term, in lower pay for many men" (2001, 831). Webb reveals one risk of monetarizing emotion work, but further research could find others. Third, the impact of emotional labor on organizational performance immediately raises the question of how one manages emotional labor. As Morris and Feldman (1996) note, organizational sanction affects how easy it is to incorporate emotional labor into one's work. Just as organization leaders define a set of values for an organization (Barnard 1938), they also need to define a set of emotions that are appropriate (or inappropriate) for the organization and the conditions under which given emotions are appropriate. Fourth, does emotional labor by public servants who deal directly with the public-street-level personnel-- interact at all with the gender composition of management? Pierce's (1997) paralegal example suggests that emotional labor might increase in organizations with male managers because street-level personnel need to adjust for the behavior of upper-level management. At the same time, one might make the opposite arguments about the link between gender and emotional labor, suggesting that female managers would be more encouraging of emotional labor. Fifth, how do the uses of emotional labor inside and outside the organization affect each other? Are they complementary? Or is there a limited supply of emotional labor that an organization can produce, so that whatever is expended inside detracts from what is available to client interactions? Sixth, does emotional labor have other impacts on the organization and its processes? This study only examined two--client participation and employee turnover. The willingness to work additional hours (perhaps uncompensated), a reduction in sick leave taken, a decline in the number of employee grievances, and a drop in adverse personnel actions are four possibilities. The form of the impacts is also worthy of study. Rafaeli and Sutton (1987) postulate that emotional labor can have short-term, long-term, and contagion effects. Contagion effects are especially interesting because they imply that the benefits to the organization will increase in a nonlinear manner as more members of the organization contribute emotional labor. In terms of short- and long-term influences, emotional labor might be similar to human capital, whereby in the short term, investments in human capital decrease production (employees are engaging in emotional labor rather than actual production), but these investments provide a stock of capital that will generate long-term increases in performance. Again, this initial attempt to estimate emotional labor and to link it to organizational performance calls attention to both the importance of emotional labor as a factor in performance and the need for further research. Quite clearly, many questions about emotional labor and its role in public organizations remain to be answered, especially when one considers the range of hypotheses linked to pay equity that Guy and Newman propose. Many of these questions are connected to the issue of measurement. This study has shown one way that emotional labor can be examined using existing data sets, but multiple-methods research involving primary data sources may prove to be the best approach to examining such a complex and nuanced workplace phenomenon. Although the approach used in this study cannot tap the interpersonal nuances of emotional labor and its many facets, it does place the concept in a multiorganizational context and tie it into an extensive literature on organizational performance. Understanding how public organizations operate and how they incorporate values has a long and honorable intellectual tradition. Emotion is a seriously understudied value that offers great promise within that tradition. Only a wide range of methods and approaches, including in-depth interviews, focus groups, participant observation and large-scale quantitative studies, can provide a full understanding of the role of emotion in organizations. References Argyris, Chris. 1964. Integrating the Individual and the Organization. New York: Wiley. Barnard, Chester I. 1938. Functions of the Executive. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. Bellas, Marcia L 1999. Emotional Labor in Academia: The Case of Professors. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 561:96-110. Blau, Peter M. 1956. Bureaucracy in Modern Society. New York: Random House. Bohte, John. 2001. School Bureaucracy and Student Performance at the Local Level. Public Administration Review 61(1): 92-99. Dilulio, John J., Jr., Gerald Garvey, and Donald F Kertl. 1993. Improving Government Performance: An Owner's Manual. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. Etzioni, Amitai. 1964. Modern Organizations. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Ferguson, Kathy E. 1984. The Feminist Case against Bureaucracy. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Fletcher, Joyce 1999. Disappearing Acts: Gender, Power, and Relational Practice at Work. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Follett, Mary Parker. 1940. Dynamic Administration. New York: Harper & Row. Glomb, Theresa M., John D. Kammeyer-Mueller, and Maria Rotundo. 2002. Emotional Labor Demands and Compensating Wage Differentials. Working Paper 08-02, University of Minnesota Industrial Relations Center. Goleman, Daniel. 1998. Working with Emotional Intelligence. New York: Bantam. Griffeth, Rodger W., Peter Horn, and Stefan Gaertner. 2000. A Meta-Analysis of Antecedents and Correlates of Employee Turnover: Update, Moderator Tests, and Research Implications for the Next Millennium. Journal of Management 26(3): 463-88. Guy, Mary Ellen, and Meredith A. Newman. 2004. Women's and Men's Jobs: Sex Segregation and Emotional Labor. Public Administration Review 64(3): 289-98. Hamermesh, Daniel S. 1993. Labor Demand. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Hanushek, Erik 1996. School Resources and Student Performance. In Does Money Matter? The Effect of School Resources on Student Achievement and Adult Success, edited by Gary Burtless. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. Hargreaves, A. 1995. Development and Desire: A Postmodern Perspective. In Professional Development in Education: New Paradigms and Practices, edited by Thomas R. Guskey and Michael Huberman. New York: Teachers College Press. Hedges, Larry V., and Rob Greenwald 1996. Have Times Changed? The Relation between School Resources and Student Performance. In Does Money Matter? The Effect of School Resources on Student Achievement and Adult Success, edited by Gary Burtless. Washington, DC: Brookings Press. Hochschild, Arlie R. 1979. Emotion Work, Feeling Rules, and Social Structure. American Journal of Sociology 85(3): 551-75. Hochschild, Arlie R. 1983. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press. Hochschild, Arlie R. 1997. The Time Bind. When Work Becomes Home and Home Becomes Work. New York: Metropolitan Books. James, Nicky. 1989. Emotional Labour: Skill and Work in the Social Regulation of Feelings. Sociological Review? 37(1): 15-42. Lynn, Laurence E., Jr., Carolyn J. Heinrich, and Carolyn J. Hill. 2001. Improving Governance: A New Logic for Empirical Research. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. Martin, Susan Ehrlich. 1999. Police Force or Police Service? Gender and Emotional Labor. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences 561: 111-26. Mastracci, Sharon H. 2003. Employment and Training Alternatives for Non-College Women: Do Redistributive Policies Really Redistribute? Policy Studies Journal 31(4): 585-601. Mastracci, Sharon H, Meredith Newman, and Mary E. Guy. 2004. Appraising Emotion Work: Determining Whether Emotional Labor Is Acknowledged in Public Service. Paper presented at the National Conference of the Midwest Political Science Association, April 15-18 Chicago, IL. McGregor, Douglas. 1960. The Human Side of Enterprise. New York: McGraw-Hill. Meier, Kenneth J., and Vicky M. Wilkins. 2002. Gender Differences in Agency Head Salaries: The Case of Public Education. Public Administration Review 62(4): 397-403. Morris, J. Andrew, and Daniel C. Feldman. 1996. The Dimensions, Antecedents, and Consequences of Emotional Labor. Academy of Management Review 21(4): 986-1010. Nias, Jennifer. 1996. Thinking about Feeling: The Emotions in Teaching. Cambridge Journal of Education 26(3): 293-306. O'Brien, Martin. 1994. The Managed Heart Revisited: Health and Social Control. Sociological Review 42(3): 393-413. Osborne, David, and Ted Gaebler. 1992. Reinventing Government: How the Entrepreneurial Spirit Is Transforming the Public Sector. Reading, PA: Addison-Wesley. Phillips, Meredith. 1997. What Makes Schools Effective? American Educational Research Journal 34(4): 633-62. Pierce, Jennifer L. 1999. Emotional Labor among Paralegals. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences 561: 127-42. Pugh, S. Douglas. 2001. Service with a Smile: Emotional Contagion in the Service Encounter. Academy of Management Journal 44(5): 1018-27. Rafaeli, Anat, and Robert I. Sutton. 1987. Expression of Emotions as Part of the Work Role. Academy of Management Review 12(1): 23-37. Sass, James S. 2000. Emotional Labor as Cultural Performance: The Communication of Caregiving in a Nonprofit Nursing Home. Western Journal of Communication 64(3): 330-59. Shuler, Sherianne, and Beverly Davenport Sypher. 2000. Seeing Emotional Labor: When Managing the Heart Enhances the Work Experience. Management Communication Quarterly 14(1): 50-89. Simon, Herbert A. 1947. Administrative Behavior. New York: Free Press. Smith, Kevin B 2003. The Ideology of Education: The Commonwealth, the Market, and Americas Schools. Albany: State University of New York Press. Smith, Kevin B., and Scott Granberg-Rademacker. 2003. Money Only Matters If You Want It To? Exposing the Normative Implications of Empirical Research. Political Research Quarterly 56: 223-32. Smith, Kevin B., and Christopher Larimer. 2004. A Mixed Relationship: Bureaucracy and School Performance. Public Administration Review 64(6): 728-36. Smith, Pam. 1988. The Emotional Labor of Nursing. Nursing Times 84: 50-51. Steinberg, Ronnie J. 1999. Emotional Labor in Job Evaluation: Redesigning Compensation Practices. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 561:143-57. Steinberg, Ronnie J., and Deborah M. Figart. 1999. Emotional Demands at Work: A Job Content Analysis. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 561: 177-91. Stivers, Camilla. 1995. Settlement Women and Bureau Men: Constructing a Usable Past for Public Administration. Public Administration Review 55(6): 522-29. Stivers, Camilla. 2002. Gender Images in Public Administration: Legitimacy and the Administrative State. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Sutton, Robert I. 1991. Maintaining Norms about Expressed Emotions: The Case of Bill Collectors. Administrative Science Quarterly 36(2): 245-68. Tilly, Chris, and Charles Tilly. 1994. Capitalist Work and Labor Markets. In The Handbook of Economic Sociology, edited by Neil J. Smelser and Richard Swedberg, 283-311. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Webb, Janette 2001. Gender, Work, and Transitions in the Local State. Work, Employment, and Society 15: 825-44. Weber, Max. 1946. From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology. Translated and edited by H. H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills. New York: Oxford University Press. Weiher, Gregory 2000. Minority Student Achievements: Passive Representation and Social Context in Schools. Journal of Politics 62(8): 886-95. Wharton, Amy S. 1993. The Affective Consequences of Service Work: Managing Emotions on the Job. Work and Occupations 20(2): 205-32. Wilson, James Q. 1989. Bureaucracy. New York: Basic Books. ADDED MATERIAL Kenneth J. Meier is the Charles H. Gregory Chair in Liberal Arts and Distinguished Professor of Political Science at Texas A & M University and a professor of public management at Cardiff University, Wales. He received the 2006 John Gaus Award for exemplary scholarship in the joint tradition of political science and public administration. His current research projects focus on building a quantitative theory of public management and the role of race, ethnicity, and gender in public policy. E-mail: kmeier@polisci.tamu.edu. Sharon Mastracci is an assistant professor in the graduate program in public administration at the University of Illinois at Chicago. She studies public personnel policies, the changing labor force, and occupational segregation by gender--the different ways that men and women find jobs, the different expectations of women and men at work, and how workplace phenomena affect women and men differently. She is the author of Breaking Out of the Pink Collar Ghetto: Policy Solutions for Non-College Women (M.E. Sharpe, 2004). E-mail: mastracc@uic.edu. Kristin Wilson is a former graduate student at Texas A & M University. She is currently pursuing a career in secondary education. Notes 1. This is also implied by economic theory along two dimensions--wages and skills--with varying implications. With respect to skills, qualitatively different skill sets would make women and men poor substitutes if the skills provided by one group tend not to be found in the other. If equipment and machinery can replace technical skills but not emotional skills, for example, then firms' investments in capital reduce the relative value of technical skills, which may jeopardize men's employment. Offshoring and outsourcing might have similar impacts. Hamermesh (1993) describes how policies that increase one group's labor cost relative to another's lower the demand for the costlier group. However, with respect to wages, because emotion work is undervalued, women may be substitutes for men in firms that are interested in lowering their wage bill for jobs that involve such skills. This could have the effect of jeopardizing men's employment in certain jobs, but it also may exacerbate occupational segregation by gender, hindering women's access to high-paying, higher-skilled jobs. 2. The argument is far more complex than is noted here. It is tied to philosophical distinctions between the public and private spheres and the assignment of traits and values to each of these spheres. The beneficial impact of emotional labor, in this context, shows the illogic of organization theories that seek to explain organizational behavior without taking concepts such as emotional labor into consideration. 3. An increase of 0.63 percent in student attendance means that approximately 26,000 more students are attending class each day of the year. 4. As an illustration, the correlation between the percentage of female teachers and average teacher salary in this data set is -.025, a figure that is not statistically significant even with more than 3,000 cases.