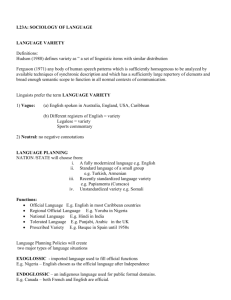

the cultural continuum: a theory of intersystems

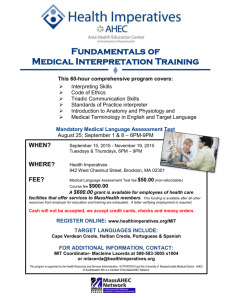

advertisement