Lesson 3 - Virtual Quarry

advertisement

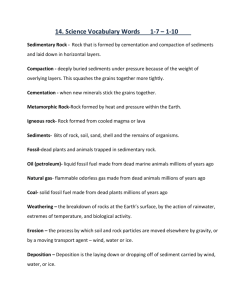

Lesson Three The tasks in Lesson Two can be repeated if necessary before the field trip using a more difficult image for the field sketch and asking questions regarding sorting of grains and cementation of the sedimentary rocks, crystal relationships in the igneous rocks and degrees of alteration in metamorphic rocks if these have been used. Lesson Four Fieldtrip or Visit to Virtual Quarry What information can be collected in the field or from secondary sources? Visit to the quarry Following a clear explanation of the Health and Safety procedures in place at the quarry students are given a brief walking tour of the area picking out examples of features identified and discussed in class. Approaching a rock face in a systematic manner Students will find it much easier to compare data from one site to another if they work in a systematic manner. It will also help to ensure they have actually looked at the rock face and recorded what they saw rather than what they thought should be there. A teacher’s information sheet is provided which could be readily adapted to provide a student worksheet. TEACHERS INFORMATION SHEET QUARRY FIELD TRIP This sheet provides a range of questions that students will have the opportunity to answer on a visit to a quarry. The first stage of the visit should consist of a linking session to the work carried out in class. What does the area look like, are you in a valley or a river basin, on a hill or a flat floodplain? Why was this quarry sited here? Are the geological materials extracted needed for building houses, libraries or courthouses, sandstone for example or Portland Stone? Does the site provide aggregates, for example sands or gravels or crushed rock? Is the material quarried used as decorative facings on prestigious buildings, Shap granite for example or maybe fossil rich limestones? On the initial walk around the site draw the students attention to specific areas of interest particularly relating to the tasks they will complete on the visit. It is important students understand the purpose of their field investigation before they start any task so they can plan their time well to ensure they complete all tasks. The approach taken here for sedimentary rocks is to try and answer the questions: What was the depositional environment? How do we use the quarried materials? Questions about shape and size of grains link to transportation and erosion Questions about sorting link to transportation Variations in the type, shape and size of grains found in adjacent beds lead to questions about changes in climatic conditions, availability of sediments Questions about cement can lead to consideration of varied transport and depositional environments For carbonate rocks investigation of fossil assemblages can lead to a range of questions about food sources, changes in salinity or influxes of clastic material from the land. Students should take a systematic approach to investigating geological outcrops. Information Sheet Information for students and teachers. This information could be produced as a handout omitting the notes for teachers, which are shown in italics, or used as a prompt for teacher led investigations. On approaching the rock face stand a little distance from it and take a good look at the whole face. This is a good point from which to make a sketch. Remember to include a scale and a compass direction and to label prominent features. Ensure students use 3 figures to record their compass reading i.e. 280 degrees or 036 degrees, not East or West Now step up to the face. Remember to wear a hard hat at all times. Do not climb on the face. Geologists like to work in pairs when examining a quarry face so they can discuss what they see, you should do the same! Depending on the size of group and number of helpers you may need to divide your group into fours rather than pairs. It is important that students’ work together, one may be very good at spotting fossils, another at measuring grain sizes. By sharing information as they work all students’ gain something from the experience. Answer the following questions: 1. What is the overall colour of the rock? 2. What is the mineralogy of the rock – can you see quartz or mica, how can you tell if you have quartz or calcite? 3. Is this a sedimentary, metamorphic or an igneous rock? Some students may require help with identifying minerals. Once you have decided which rock type you have you will need to ask different questions of each type of rock. If you have SEDIMENTARY ROCK Is it a clastic sedimentary rock or a carbonate sedimentary rock? Students can test with dilute hydrochloric acid if they are unsure If it is a CLASTIC SEDIMENTARY ROCK 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. What is the grain shape? What is the grain size? How well are the minerals sorted? What is the cement? Can you see bedding? Are any sedimentary structures visible? Each of steps 1 – 6 benefit from a small sketch to support your written answers, remember to include a scale and to say whereabouts in the quarry face the sketch was taken from 8. What can you say about the depositional environment? Grain shape is an important indicator of the degree of transportation the mineral has undergone. As the mineral is eroded so any sharp angular points will be worn away, the grain becomes progressively rounded. This is not the same as becoming a sphere. Sphericity refers to how ball like the grain is, will it roll in the palm of your hand like a marble for example. A long thin grain can still be well rounded even though it is not a sphere. Sorting is another important indicator of transportation. As rock fragments and minerals are transported some, such as feldspar, will react chemically with water and eventually go into solution. Others, such as mica may be trapped in the slow moving waters and silts at the edge of a river. If the sediment being examined is mainly quartz it is said to be very well sorted, a mixture of quartz, mica, feldspar would be classed as poorly sorted and if there were rock fragments amongst that mixture it would be very poorly sorted. If the cement is quartz the rock will be hardwearing, usually light in colour. If the cement is iron the rock will have a reddy brown appearance and may be quite friable. This is an important feature to consider when deciding what will make a good building stone. All sediments are laid down horizontally; the mass of sediment laid down during any one event is described as a bed. Bed thickness cannot tell you anything about the length of time deposition continued for, a thin bed may have taken many thousands of years to be deposited if there was little sediment available whilst a thick bed may have been deposited rapidly if the sediments were being transported from a weathering mountain range. The gaps between the beds are every bit as important as the beds themselves. Can students see ripples on the top of the beds, are there weathered particles from the top of one bed incorporated into the base of the next, has a soil formed at some time on the top of a bed? These clues all tell us that deposition stopped for a time, a soil tells us that the rock was exposed at the surface of the Earth. Sedimentary structures may include graded bedding, a structure showing that heavier particles were deposited first and then progressively lighter particles deposited as velocity dropped. There may be ripples, or evidence of dunes, there may be load casts. Load casts form when new sediment is washed on to existing sediment, which has not yet lithified (become rock). If the new sediment is denser than the pre-existing material it may sink into it in places and students will be able to see the resultant ball like structure which forms. Depositional environments vary from river to estuary to glacial meltwaters. If these sediments were laid down in an estuarine environment there are likely to be more muds than sands, if glacial then a range of sediment sizes from at least cobbles to sands will be evident. If it is a CARBONATE ROCK 1. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Can you see fossils? Are they abundant? Is there a diversity of organisms? Are the shells whole, broken or crushed? What type of organisms can you see? Do you know if the organisms were swimmers, filter feeders or burrowers? What can you say about the depositional environment? Once students have recognised fossils in the rock then they need to gather information that will help them identify the conditions prevailing when the organisms were alive. If fossils are abundant this shows there was a ready food source, it is likely the waters were relatively shallow and warm as this encourages productivity. If there is a wide diversity of organisms this suggests that conditions were stable, few organisms can live in waters with low pH or excessive mineral salts for example. If those conditions prevailed there might be an abundance of one type of organism exploiting the environment but there would not be a range of different organisms. If the shells are whole then burial was rapid following death or indeed the sediments covering the organisms may have been the cause of death. Broken or crushed shells indicate high-energy environments, storms or transport towards a beach where strong currents and tides broke up the shells. Identification sheets can be obtained from the British Geological Survey (www.bgs.org.uk) or may be provided as part of a teachers pack by the education section of a fossil rich quarry. The type of organism found can give clues to the environment, burrowers may be escaping predators but could also be escaping the variable conditions found near to shore. Swimmers may show adaptations to protect them from predation, ornamentation on their shells for example to make them more difficult to grip or the ability to swim rapidly backwards! All of these points should help answer the question regarding depositional environments. If you are in a SAND AND/OR GRAVEL QUARRY Working sand and gravel quarries are usually only open to school parties as part of a guided tour however if requested most quarries will attempt to support some primary exploration in an area they consider safe. The United Kingdom has identified a number of Regionally Important Geological Sites (www.rigs.uk) in disused sand and gravel quarries and there is a variety of literature available which could support a classroom-based investigation. You should take the same systematic approach. On approaching the quarry face stand a little distance from it and take a good look at the whole face. This is a good point from which to make a sketch. Remember to include a scale and a compass direction and to label prominent features. Can you see any large-scale features; is the deposit a dune for example? Students should be able to see the inclined bedding of a large dune; often there are changes in the colour or size of grains, which help to pick out the shape of the dune. Now step up to the face. Remember to wear a hard hat at all times. Do not climb on the face. 1. 2. 3. 4. What shape are the grains? Can you identify any minerals? If there are gravels what shape are they? Are the sands and gravels sorted? Remember sands and gravels are moved by a fluid, usually water, and deposited as the velocity of the fluid drops, heaviest first then progressively lighter material. Use a hand lens and a tape measure to identify the shape and the size of the grains in your area. 5. Draw a sketch to show how shape/size alters as you move from the bottom of the section upwards. 6. Look closely at the grains; can you see clay particles in the sand and gravels? Clay particles often make the sands and gravels look dirty or dusty. 7. What can you say about the depositional environment? Grain shape, size and mineralogy are all important tools for helping to determine if the sediments have been transported by river or melt water. Sorting is also a useful clue to depositional environments. Ask the students to imagine the sediment load of a river and then to imagine that river in flood. What would happen to the sediments? They would be deposited on the floodplain but would not be sorted, there would be a jumble of sizes and shapes dropped as soon as the water’s velocity fell as the river over banked. What other situation could the students suggest where this lack of sorting might be apparent, rock falls, scree slopes for example. Trying to produce a useful sketch of the grain relationships in loose sands and gravels requires a different approach. It is best to draw a measured section, recording changes in grain size and identifying any specific features found i.e. sands with shell fragments. Why would anyone need to know if there were clays in amongst the sands and gravels? Sands and gravels will be used as aggregates by the construction industry, clay will need to be washed away before the aggregate can be used and so the cost of extracting the aggregate is significantly increased if there is a high percentage of clay mineral amongst the grains. It is useful to bring students together at intervals during the quarry face exercise to ensure there are no real problems, to answer general questions, to share any exciting finds, to ask students to share information. Remind students of the reason for being there – to find out about depositional environments and to consider the uses of the material quarried. If you have IGNEOUS ROCK You should take the same systematic approach. On approaching the quarry face stand a little distance from it and take a good look at the whole face. This is a good point from which to make a sketch. Remember to include a scale and a compass direction and to label prominent features. At the rock face ask the following questions: 1. What size are the crystals? 2. What shape are they? 3. Choose a small area (about the size of a 50 pence piece) that gives a good representation of the minerals in the rock and their shape and size relationships and make a sketch of it. Using a handlens will help. Remember to include a scale. 4. Is the rock intrusive or extrusive? 5. Can you say something about the environment it was deposited in e.g. is this a small intrusion of igneous rock which has forced its way into sediments or is the whole quarry comprised of igneous rock? 6. How is the rock weathering? Can you see iron staining, broken fragments at the base of the rock face? Students measure a selection of minerals in order to give a true representation of the rock as a whole. They should recall that crystal size reflects cooling rates and helps determine if the rock is intrusive or extrusive, crystals visible to the naked eye mean the magma cooled in the Earth at a slow rate. The sketch should include each mineral showing the way it fits with neighbouring crystals. If the rock being examined is similar throughout then students need only draw a small section. It is important they do not draw a “currant bun” a circle with 2 or 3 crystals in it, igneous rocks are crystalline, there are no gaps between the crystals! It may be difficult for students to determine how the rock was emplaced; you may need to make reference to the geological map of the area if this is a large intrusion. If the igneous rock has formed as a smaller emplacement, say a sill or dyke, which has forced its way through the country rock then students may be able to see the contact point. If so they may also be able to identify a change in the size of the crystals in the igneous intrusion. Magma next to the country rock will have lost heat more quickly than that in the centre of the intrusion; although the crystals will still be easily identified they will be smaller than those further away from the country rock. If the igneous rock formed as a lava flow then evidence of escaping gas bubbles or difference in crystal size between the top of the flow and the base should provide helpful clues for students. Look for evidence of chemical and physical weathering; think about the climatic conditions in the area. On the highest parts of Dartmoor for example the temperature rarely rises above 6C during the winter months and regularly falls below zero at night. Along the coast of Devon and Cornwall the temperatures may not be so harsh but igneous exposures will be attacked by salt spray. Before leaving the quarry call the students together and discuss their findings, linking to the original question about depositional environments. Then ask them to consider the evidence they have seen of the Rock cycle in action, of weathering processes so they are able to link their work in the quarry to the main task associated with the field trip.