British geopolitical game during WWI and the controversy over the

advertisement

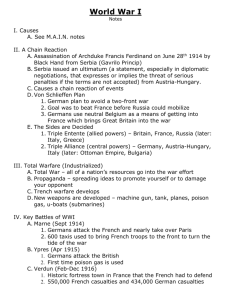

Defence & Security Series Author: John Karkazis Issue D2, April 2004 THE BRITISH GEO-POLITICAL GAME DURING WWI AND THE CONTROVERSY OVER THE BATTLE OF SOMME (extracts) ……….. CONTENTS THE WAR IN 1914 THE WAR IN 1915 THE WAR IN 1916 THE WAR IN 1917 THE WAR IN 1914 The Germans were well-prepared for a two-front war, against France and Russia. Their highly efficient rail network offered them the option of a rapid transfer of troops from one front to the other. With the start of war Germans made two grave mistakes. The first mistake, to attack France via Belgium, was a strategic one and provoked the immediate British reaction. The violation of Belgium’s integrity was a foolish decision on the part of Wilhelm II who gambled against the possibility of British decisiveness to defend their vital interests in the Belgian barrier. This foolish decision was compatible with the lack of diplomatic instinct and the adventurous personality of the German Emperor who looked down on the lessons taught by Bismarck’s diplomatic history. The second mistake was a tactical one. In the most critical moment of the German offensive in France (three weeks after the start of the war) Germany withdrew considerable forces from the western front and transferred them to the eastern front to fight against two Russian armies which were advancing into East Prussia. This resulted in the loss of momentum in the German offensive. The French exploited this favorable situation and with the support of a small British force attacked Germans and won, in September, the critical Battle of Marne forcing them to retreat. From thereon the war in the western front was reduced to a war of trenches and positions. A similar mistake was made a quarter of a century later by Hitler who decided, in the most critical moment of the Battle of Britain, to withdraw considerable air forces from the primal target of the German offensive against Britain’s key air force installations, and to divert them to attacks against London which had no strategic impact beyond the satisfaction of the lower instincts of the German public. In the eastern front the German armies under general Lundendorff were victorious: they won the battles of Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes and captured more than 200.000 Russians (see appendix 5). THE WAR IN 1915 During the second year of the war the German and the Austro-Hungarian armies pushed forward with the offensive against Russia, capturing large territories of Russia and inflicting enormous casualties on the Russian army which amounted to 2 millions of soldiers killed, wounded or captured. During this year the Allied powers opened a new war front in the Balkans by dispatching to the Dardanelles huge land and naval forces with the land ones amounting to almost half a million soldiers mainly of colonial origin. The most obvious aim of this offensive was to capture Constantinople and the straits and open up communications with Russia at a moment it was facing enormous pressures. Another, heretic, explanation of this offensive was to capture and safeguard Constantinople before the Russian whose army was victoriously advancing in the Caucausus region. The Dardanelles offensive turned into a disastrous fiasco during which 150.000 allied troops were lost. In the western front the situation was settled down to a devastating (for France and Germany) stalemate. During this year the British imposed a naval blockade of Central Powers territories abolishing the existing international agreements which distinguished contraband against non-contraband trade. The Germans counter-reacted by imposing their own blockade of British Isles which proved to be ineffective. During 1915 a series of secret treaties were signed by the Allied powers. These treaties regarded colonial issues and the division of the Ottoman Empire into zones of influence according to the Chinese paradigm of late 19th century. To openly deal with these issues was a very dangerous matter especially in view of the American sensitivities on these issues which, in 1918, with Wilson’s 14 points Doctrine, were upgraded to almost a ‘red line’, imposing a strategic threat on Britain’s colonial system and policies. As a consequence, the British and French were forced to impose the secret character of these treaties. With the first secret treaty (Treaty of London in 1915) the Allied powers succeeded in drawing Italy to their side by offering it colonial territories in Africa of secondary strategic importance. By a second treaty in 1915, the Allied powers agreed (or promised) to offer Tsar Constantinople and the Dardanelles. Since this issue was of paramount importance for them, the British worked on a treaty too intricate and obscure to be implemented at the end in favor of Russia. On the other hand the British were expecting that, in a prolonged war, the tsarist regime will collapse and with it the validity of such an agreement. Furthermore, there exist certain facts, related to the slipping of the German warships Goeben and Breaslau into the safety of Dardanelles, after having crossed the Mediterranean Sea west to east undetected (?) by the British naval forces, which facts support the argument (with almost evidential reasoning) that the British exploited this issue in order to achieve the following: (a) either weaken Russia’s naval forces in the Black Sea (actually these warships were employed by the Germans under Turkish flag against the tsarist fleet there) or (b) force Turkey into the arms of Germany giving thus Britain the opportunity to treat Ottomans as an enemy of the Allied powers and consequently offer the British the opportunity to implement easier the division of the Ottoman Empire, or (c) both the above options THE WAR IN 1916 Since early 1916 Germany and its allies had started to feel the effects of the British naval blockade. Britain repeated with success the paradigm of economic war of early 19th century, that time against Napoleonic France this time against Central Powers. The British blockade was imposed on its enemies despite the pressures from US which insisted that its “freedom of the seas” dogma should be respected. This situation created serious frictions between US and Britain that were added to the discomfort felt by the Americans and especially by their President as a result of Britain’s imperialistic policies and secret treaties. At the beginning of 1916 the general trend of events was favorable for the British except for two issues that will be analyzed later: its new and old enemies and adversaries in Europe were destroying each other with great zeal, the colonial system of Germany was ready to collapse and the Ottoman Empire was at the final stage of its disintegration with nobody else being able to fill the vacuum except the British. All were going well for Britain except for two issues: the first, and most crucial one, was the anti-colonial and “open-sea” policies of President Wilson (the greatest ever threat against British Empire) and the second was the anxiously expected showing of the full strength of Germany’s naval power in the Atlantic Ocean, since in the battle of Helgoland, on the part of Germany, only coastal warships took place (and they were easily defeated by the British). The great opportunity for the Emperor Wilhelm II, to prove that his country’s tremendous efforts to built the highly expensive High Seas Fleet had satisfied the ‘value-for-money’ principle and also to show to his people that Germany could retain some (minor) hopes to win the war, came in May 1916. During this month the great and most decisive battle of World War I, the naval battle of Jutland, took place between the British Grand Fleet the German High Seas Fleet. After an almost indecisive outcome (big losses were suffered by both sides) the Germans withdrew their naval forces behind their minefields protective barrier, proving how well they knew to built and operate warships but at the same time how much unable they were to translate into geo-strategic power the power of their fleet. At the end of May 1916 the strategic phase of the war was over for the British. From thereon they possessed enough naval power and time but above all enough confidence to face the main strategic threat imposed by President Wilson. On the other hand, if US would have the opportunity to join the war in Europe then their demanding President would be offered the opportunity to impose more effectively his anticolonial dogma on the European colonial powers. The events following the decisive battle of Jutland exposed with enough clarity British plans. First of all, the summer of 1916 marked the beginning of one of the most crucial (both for American and British interests) presidential election campaigns in the American history, a campaign of the highest importance for the American public which was still against the involvement of US in the war in Europe despite the ‘Lusitania Incident’ (the sinking, in 1915, of a British liner with military cargo onboard by a German submarine during which 118 Americans were lost). The Americans did not want to suffer sacrifices by participating in a horrific war thousands of miles away and in support of powers which were heavily criticized by their President for their imperialistic policies. It was a period during which the lights of publicity had been heavily thrown upon the European theaters of war. In view of the above attitudes of the American public, it was more than obvious that the projection of the horrific trench warfare realities of the western front to the American public will make it to think twice before empowering the government to send the American youth to the European slaughterhouse. On the other hand, the prevailing perception was that the British were working hard to draw US into the war. In the middle of this crucial, for Britain’s vital interests, presidential elections campaign, in July 1916, the British decided to be engaged in an all out offensive against the Germans, the famous Battle of Somme, in the first day of which the British generals sent to death 60.000 soldiers employing highly controversial and heavily criticized battle tactics. At a first glance, one may assume that the particularly cautious and studious British diplomacy and its equally cautious and not at all light-headed military apparatus had made their first strategic mistake in the war with the unfortunate handling of this battle, an assumption not at all compatible with British historical evidence and consequently extremely surprising. The assumption of a British strategic mistake suffers an almost lethal strike by the following totally amazing events that took place shortly after the controversial battle. At the end of September 1916, during the most critical moments of the campaign the British dispatched Charles Urban, the official photographer of the British government, to US to arrange for a private exhibition of a motion picture of the Battle of Somme. As the New York Times reported on this film in September 30, 1916 (see appendix 1) “…every detail of the forward movement…from artillery preparation to the bringing back of wounded and prisoners … is recorded in these films…the pictures of the returning wounded and the winrows of dead are for the strong only”. The above events speak of themselves. The privacy of the exhibition was most probably arranged as a cover up of the real intentions of the British since nobody could rely on the self-censorship of the audience of these films (probably including among them journalists and other influential personalities) on such an issue and at such a moment. Conclusively, there exists plenty of evidence to support the addition of a new hypothesis in the efforts to explain the highly controversial events of that period, the hypothesis of staging or exploiting the horrific events of the battle of Somme in order to create a repulsive mood in the American public just before the Autumn 1916 presidential elections (the theory of provocation of American isolationism). THE WAR IN 1917 In early 1917 the effects of British naval blockade on Central Powers and especially on Germany were intensified. Lundendorff, to alleviate the effects of British economic war on Germany, decided to gamble with the American participation in the war and ordered the German submarines (known as U-boats) to start massive and indiscriminate attacks on convoys transporting supplies from US to Britain. The effectiveness of German submarine warfare soon started to decrease as a result of tactical and technological advancements in the anti-submarine operations of the British and the Americans. On the other hand this decision of Lundendorff forced the Americans (or offered them the final excuse) to join the war in Europe. If Lundendorff had other (hidden) aims in mind besides the obvious ones, that proved to be catastrophic for his country, is an interesting issue but extremely difficult to explore. To a desperate attempt to prevent Americans from joining the war the German Emperor, following the adventurous steps of Napoleon III, tried to form an alliance with Mexico and Japan (against US) which would enable Mexico, in due time, to reclaim lost territories to US (New Mexico, Texas and Arizona). As it was expected, this foolish plan failed but at the same time pushed further the Americans towards their decision to join the war. In the eastern front Russia was in an advanced state of disarray. The Germans channeled more fuel to the internal fire in Russia by allowing Lenin to slip through German territories into Russia and take the leadership of the Bolshevicks revolution in October 1917. At the end of the year the Germans forced Bolshevicks to sign a humiliating peace treaty by which they were annexing huge territories from Russia. At the same time, the British defeated the Ottomans in the Near East imposing their rule on Palestine and destroyed the colonial system of Germans in Africa. ……………… Appendix 1 THE BATTLE OF SOMME IN FILM Published: September 30, 1916 Copyright © The New York Times (see next page)