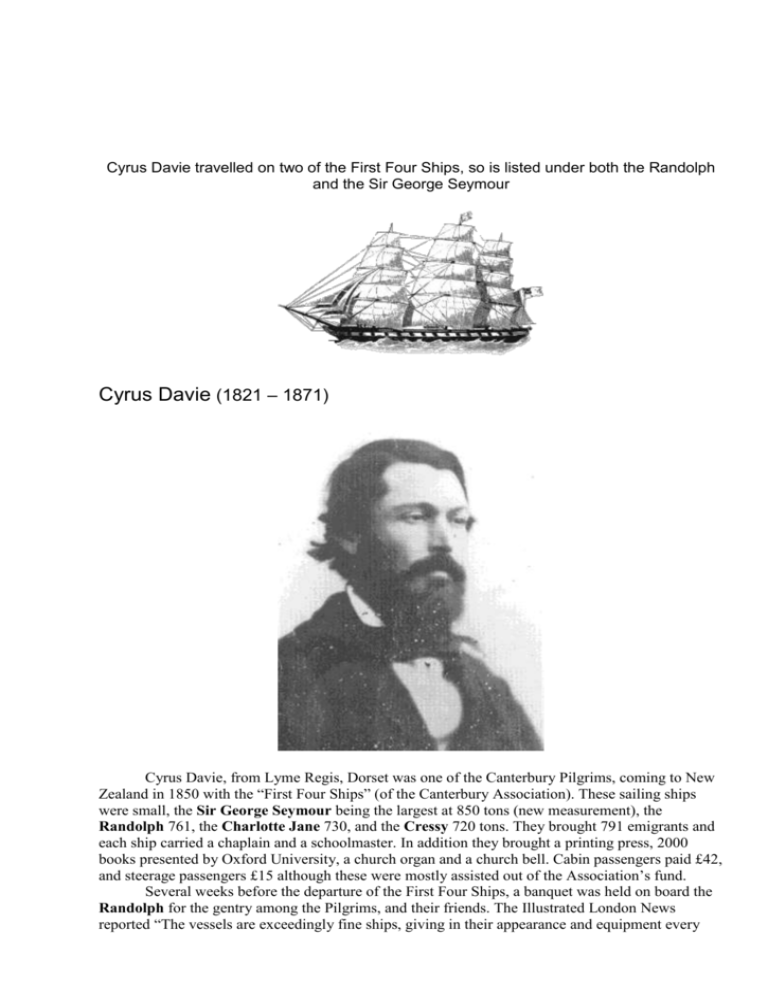

Cyrus Davie (1821 – 1871)

advertisement

Cyrus Davie travelled on two of the First Four Ships, so is listed under both the Randolph and the Sir George Seymour Cyrus Davie (1821 – 1871) Cyrus Davie, from Lyme Regis, Dorset was one of the Canterbury Pilgrims, coming to New Zealand in 1850 with the “First Four Ships” (of the Canterbury Association). These sailing ships were small, the Sir George Seymour being the largest at 850 tons (new measurement), the Randolph 761, the Charlotte Jane 730, and the Cressy 720 tons. They brought 791 emigrants and each ship carried a chaplain and a schoolmaster. In addition they brought a printing press, 2000 books presented by Oxford University, a church organ and a church bell. Cabin passengers paid £42, and steerage passengers £15 although these were mostly assisted out of the Association’s fund. Several weeks before the departure of the First Four Ships, a banquet was held on board the Randolph for the gentry among the Pilgrims, and their friends. The Illustrated London News reported “The vessels are exceedingly fine ships, giving in their appearance and equipment every reason to anticipate a safe and prosperous passage; the day appointed for sailing being the 29th August… On the lower deck of the Randolph four tables were laid, occupying the whole length of the ship, and covered with an elegant dejeuner a la fourchette for 340 persons. Of the company which assembled, about 160 consisted of actual colonists and their families, whose passages are taken in the ships… A large proportion of these colonists belong to the gentry class at home; and inquiry has satisfied us that they are distinguished from the mass of emigrating colonists no less by high personal character, than by their social position at home; that they are not driven from the mother-country by the pressure of adverse circumstances, but are attracted to the colony by the prospects which its singular organization holds out.” A month later a dinner was held for the rest of the emigrants. Cyrus Davie’s claim to fame was that he actually travelled on two of the ships. He was booked as a paying passenger on the Randolph, on which his luggage was loaded but for some reason he missed the sailing. One might speculate why; that he had been given the incorrect time of departure; that the ship sailed early because of favourable tide or weather conditions or the family story that he was saying a fond farewell to his fiancée, Emma Mortimer. Colin Amodeo (The Summer Ships) believes that the captains may have had wagers on which ship would make the fastest passage. About 7 days before the colonists left England, they attended a service at St Paul’s Cathedral. We don’t know whether Cyrus went to London for this, but he is recorded as embarking at London as did most of the passengers; the ships sailed from Gravesend (on the lower River Thames) and were stopping at Plymouth only briefly to pick up a few people and some extra supplies. In the list of the passengers of the First Four Ships published by ‘The Press’, only two families (of 7 and 9 people) and three other adults embarked on the Randolph at Plymouth. It seems that Cyrus went to London intending to go on board there, loaded his luggage and then suddenly decided to travel overland and join the Randolph at Plymouth (visiting Emma on the way?) As the last link of the railway to Plymouth was completed in 1848, he could have travelled by train. In 1851 Emma Mortimer was working as a governess at Seaton, which is a couple of miles from Colyton, the home of her sister, Mrs Elizabeth Snook. At times she lived with an uncle on Plymouth Hoe and could well have been in Plymouth when the ships called there in September 1850. Before the ships sailed, a list of purchasers of land in the Canterbury Settlement was published (the Canterbury Papers, No 8). This list contains about 140 names and as Cyrus Davie’s name is not included, it could be that he only decided to come to New Zealand at a very late stage, and may have had last minute business to which he had to attend before leaving England. Richard JP Fleming, a passenger on the Randolph, describes in his diary of his trip to New Zealand, first the voyage from London to Plymouth, passing the Sir George Seymour in the English Channel on the forenoon of Sep 6th. At Plymouth, on 7th Sep; “Several passengers joined the ship….All passengers joined the ship excepting Mr Davie, Chief Cabin passenger. 8pm, weighed anchor and made sail”. Another passenger, Joseph L Parsons says in his diary; “Sep 7; We were rowed in a small boat to the ship Randolph somewhere about 4pm…leaving about 9pm under a light breeze”. Charles J Bridge “Left the English shores in the boat for the ship Randolph at half past three. The Charlotte Jane set sale (sic) about eight o’clock and we followed her example about nine o’clock.” The Randolph’s Captain obviously didn’t want the Charlotte Jane to get too far ahead. Dr A.C.Barker, surgeon on the Charlotte Jane writes “All day and the day before we were followed down the Channel by one of our ships, the Randolph, which at last passed us and reached Plymouth a quarter of a mile in front of us. We were all much struck by the beauty of Plymouth Sound. During the night, the child of one of the emigrants died, and the first thing in the morning I put off to the land to make arrangements about its burial. However I had speedily to return as it was quite uncertain when the ship was to sail. The great doubtfulness of the ship’s stay prevented my wife’s going on shore and I did not venture after the morning.” His wife writes “The utter confusion of sailing as well as arriving at Plymouth is indescribable.” Local historian Frances Ryman believes that William Guise Brittan, who was chairman of the settlers committee, helped persuade the captain of the Sir George Seymour (which sailed from Plymouth the next morning, Sunday Sep 8th 1850) to allow Cyrus to embark on his ship. In his journal of the voyage, Cyrus makes no mention of why he missed his ship. “Sunday 8th September. Embarked from the Barbican, Plymouth, and arrived on board about 7am. Weighed anchor at 10am. We lost sight of Old England with the closing day”.* It would seem that the ships left the shores of England (Plymouth Sound) as soon after midnight as possible as this gave them more hours in the first day of sailing in the informal competition to make the fastest voyage. Accounts by passengers appeared in the Lyttelton Times on January 11th 1851; The Charlotte Jane left Plymouth Sound at midnight on Saturday 7th September… and cast anchor off Port Lyttelton on 16th December, thus making her passage in 99 days from port to port…. The Randolph left Plymouth on the night of Saturday, 7th September, a few hours after the Charlotte Jane… she entered Port Victoria on the 16th December, having accomplished the passage in 99 days…. The Sir George Seymour weighed anchor at Plymouth about eleven am on Sunday September 8th. She was the last, by several hours, to leave the shores of Old England. She came to anchor on 17th December, being 100 days from the time she left Plymouth. The Cressy left Plymouth at midnight on September 7th, and at last anchored in Port Victoria on the 27th December, being 110 days. The Captain deserves our thanks for consulting the health and comfort of his passengers in not running further to the southward, when a shorter passage might have been made in colder latitudes. *In 2003 I visited the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington and looked at a copy of Cyrus Davie’s journal of his voyage to New Zealand. I expected it to be just another copy of the original journal, which is held in the Canterbury Museum, but I found that it is a different (sanitised) version, written by Cyrus after he had arrived in New Zealand, presumably to send back home to the family in England (Emma Mortimer, his fiancée; and his mother and siblings). Immediately, with his first words, Cyrus partly answers the question as to why he missed his boat “Arrived at Plymouth at half past 6 am having missed the Train the previous evening”. We still don’t know why he missed the train, but that explains why he missed the boat. Cyrus labels this ‘copy 1’, and although mostly copied from his original journal, it is written in a more chatty style – as though he is talking to someone and not just making notes. He changes some words (jetty to pier), and makes very positive comments on the voyage (not to discourage Emma from making the voyage?) He has change the facts in one case – when he visited the Deans’ farm, their party met some natives, on the way to the Deans’ farm in the first version, and on the way back to Lyttelton in this second version. Exerpts from this copy, which is written very neatly in Cyrus’s small, but very legible handwriting. Copy 1 Journal of a Voyage from Plymouth to Port Victoria or Cooper, or Lyttelton, Canterbury, New Zealand in the “Sir George Seymour” of London – Captain Goodson. 1850 Sunday Arrived at Plymouth at half past 6 am having missed the Train the previous Sep 8 Evening and on going out to the Sound found that the Randolph, the Ship in which I had taken my passage, had sailed in the middle of the night – a letter written to me by the Shipping Agent Mr Bowler, had I suppose miscarried, at all events I never received it or I should have been earlier – The Cressy and Charlotte Jane had also sailed at the same time only the Sir George Seymour which with the Blue Peter flying at the main was waiting for the latest dispatches from London. [The Blue Peter is the signal for sailing – recalling everyone to their ship]. I went on board and found that the Captain would not assist or receive me as the ship was already overfull of passengers. The surgeon-superintendent advised me to go to Mr Bowler, who with Wilcox, the other agent, was then at the office, and offered to supply me with a hammock etc from the Hospital if I could get their order from the Captain to receive me. I again went on shore and after some parley, went back with them to the ship. We immediately weighed anchor at 10am and passed close to the Albion, 90-gun ship and rounded the western end of the breakwater at 1. The visitors then left, after giving us three cheers which were as heartily returned. We then stood and with all sail set having a fine breeze from the east, a cloudless sky, and all nature --? At sunset we were well off the Lizard, course SW we lost sight of Old England with the closing day. Sep 9 A very small party at dinner today and still fewer at tea. I never felt better or more hungry (just as I was between Nieuport and Lym) and can walk the deck pretty well… Several cabins flooded from the Scuttles [hatch-way covering] not being properly secured. Transfer Mid-Ocean When the Randolph was sighted about a month out from England, Cyrus was transferred by boat in mid-ocean. Naturally this caused quite a commotion and gave the passengers something to talk about for days. Friday 4th Oct. “At day-break this morning the four ships of yesterday astern on the port side; over the port bow another ship steering as ourselves. This last ship tacked and stood towards us on a parallel course, we east, she west. Bets were offered at 16 to 1 on her appearing through a squall that she was the Randolph.” It was, and so the Sir George Seymour immediately signaled that one of their passengers was on board. “She sent a whale boat with a party who boarded us. I went with them on board the Randolph, and thus quarter of our voyage being over gained my ship in the midst of the ocean – an occurrence which I suppose never before occurred with a passenger; leaving many friends [one of these friends was R. J. S. Harman] in the Sir George Seymour with whom I hope to spend many pleasant days in our adopted country, and carrying many, many introductions to my fellow-passengers. I found myself a Lion at dinner.” Edward Ward, who sailed in the Charlotte Jane, says in his journal of 3rd Oct “About four p.m. sighted a large ship on the opposite tack…she did not come near enough to signalize, but went unknown on her way. We, as usual, pronounced her to be, first the Randolph, next the Sir George Seymour, as if those were the only two ships on the sea just now”. Charles Joseph Bridge also kept a journal of his voyage on the Randolph and in his account of the 4th Oct writes; “Saw a ship in the distance which the captain thought looked like the Sir George Seymour. Upon signaling her we ascertained that it was her. She told us that they had one of our passengers on board whom we had left behind at Plymouth. When we came near her we lowered a boat and went on board her, we found all well and after staying about half an hour we bade them goodbye and taking our stray passenger with us we regained our ship after a hard pull.” (this stray passenger being Cyrus Davie, who shared Mr Bridge’s cabin, and the friendship then began has continued in the succeeding generations.) Richard Fleming writes; “Oct 4; Saw a ship in the distance which proved to be the Sir George Seymour, signaled her and found they had a passenger on board who had missed our vessel when we left Plymouth. We bore down to her, then lowered the boat and fetched him out on board our vessel”. And Joseph Parson’s comment for that day “Telegraphed Sir George Seymour and lowered a boat to fetch Mr Davy – who was left behind by us at Plymouth owing to his not showing”. From the account of the voyage of the Sir George Seymour in the Canterbury Papers (18501852); “An incident occurred which we must not pass over. A sail came into sight, which proved to be the Randolph. Nothing could have happened more fortunately, since it gave an opportunity to our friend Mr Davie to pass the rest of his time in his own ship. He had narrowly missed his passage altogether, having arrived at Plymouth too late to embark on board the Randolph, and was with difficulty permitted to take his passage with us. An opportunity was now afforded, most unexpectedly, of putting him in possession of his own cabin, in his own ship. There was not one, it may safely be said, who was not sorry to lose him from amongst us: still, we could not but congratulate him on the now probable recovery of his cabin and his outfit. The expectation was realized; a boat was lowered from the Randolph, and the chief officer and some other passengers came on board to visit us, and after a short stay, returned in company with our friend, who has thus succeeded in accomplishing a feat, more often talked of than performed – namely, that of sailing in two ships, an honour supposed to be reserved only for the most distinguished personages.” The story is told 50 years later in “Canterbury Old and New 1850-1900, A souvenir”. SC Farr writes – “A strange coincidence occurred in connection with the Randolph and Sir George Seymour, the only two of the four ships that sighted each other on the voyage out. Mr Cyrus Davy, who was booked as a passenger by the Randolph, and had all his luggage on board that vessel, missed his passage, and embarked in the Sir George Seymour, which sailed the following day. To find his own ship in mid-ocean, and finish his voyage in her, was probably the last thing he expected – yet such was his experience. The Sir George Seymour signalled to the Randolph to send a boat for the passenger, which was done, several gentlemen on board taking this rarest of opportunities to pay a visit to their fellow voyagers in the sister ship.” And in 1916 Henry Wigram writes in his “Story of Christchurch, NZ”; ‘During the long voyage only two of the four vessels had spoken each other, the Randolph and the Sir George Seymour, and their meeting in mid-ocean was marked by a curious incident. One of the Randolph’s passengers, Mr. Cyrus Davy, who had missed his passage and had been taken on by the Sir George Seymour was transferred to the former ship and enabled to rejoin his luggage.’ In 2002, Jennifer Queree writes in “Set Sail for Canterbury”; ‘The only known journal of a passenger on the Sir George Seymour is that of Cyrus Davie, who had the distinction of missing his designated ship, the Randolph, at Plymouth, joining instead the Sir George Seymour and being reunited with the Randolph on 4 October after a chance meeting on the high seas off the coast of Africa almost a month later. Davie was of a reserved nature and, compared to many diarists of the period, was unusually discrete in his references to his fellow passengers. He mentioned by name only “Mr Jacobs” (a clergyman and later Dean of Christchurch), and “Mr [Joseph] Dicken”, with whom Davie struck up a friendship. Some of the entries in his journal reveal the initial experiences of the newly-launched colonists’. Queree uses some of these in the book. During the voyage Keen interest was shown in the progress of the ships; the passengers were always looking out for the other ships and hoping that they were making better progress. It does seem that the ships were unofficially racing each other. Edward Ward’s Journal: Oct 5th “ The Captain very savage at the foul wind which is carrying us so far to the East….. On deck in the course of a lecture from the Captain, heard that very heavy bets have been laid about the respective rates of sailing of our four ships – that Randolph is the favourite and we are next. Oct 15th: Fine fresh-blowing breeze, a clear run of 200 miles. This is considered a most extra ordinary run for a merchant vessel, the Captain is accordingly in high spirits. Nov 1st: Captain took Fitzgerald’s two to one in bottles of champagne that we would not cast anchor in Lyttelton harbour within 98 days from Plymouth. Wortley bet me that we would not be there in 95. Nov 25th: Captain’s average per day to bring us in in 98 days reduced to 151 miles. Nov 29th: Took ten to one from the Captain that we would not be in in 95 days after all. Dec 2nd: Took 3 to 1 from Wortley that we should not be in in 100 days. Dec 15th: “At dinner we had the champagne which I and the Captain lost to Wortley and FitzGerald – the 98 days, in favour of which we bet, having expired today at noon. Dr A.C.Barker writes “For the first day or two the Randolph kept in sight of us, but gradually dropped astern and now has not been seen for more than a week. October 10th; the wind has been very contrary, obliging us to tack, to the great mortification of the Captain, who seems afraid the other ships have taken a course outside the Canaries and have got more favourable winds. October 19th. We overtook a ship sailing in our direction and spoke to her, finding she was the Grassmere from Liverpool bound for Calcutta, and that she had been out 60 days, a matter of no small congratulation among ourselves as we had been out only 45 from London. She also informed us that she had not met either of our rivals, the Sir George Seymour or the Randolph, so we hope that we are still ahead of them.” Cyrus writes on the day after he changed ships “The Sir George Seymour on our starboard beam distant 7 miles. A fine breeze and each ship doing her best… At night we have gained on her and can see the emigrants on the forecastle placed there to keep her in better trim.” The next day “The wind could not be worse. We go 160 miles to make 30.” Chief Cabin On the passenger lists for the First Four Ships both Cyrus Davie and C.J. Bridge are listed as single men, occupation is given as gentleman, fare as paid, type as colonist (not emigrants who had assisted passage) and the accommodation was chief cabin. The colonists as distinct from the emigrants were men of status, education and capacity for leadership who came from the English middle and upper classes. Many shared the Association’s vision of planting a reinvigorated church in a new land. Chief Cabin passengers provided their own furniture, bedding and whatever else they wanted within their cabins. The ship provided plates, cutlery and the food, which was cooked and served. “The Captain presides at his own Table; the passengers are considered his guests; and in deportment and dress they are expected to govern themselves accordingly.” - Memorandum for Passengers. Although definitely feeling themselves superior to the emigrants, both men showed some compassion towards them. Cyrus; “ One gentleman, likely to be a great friend of mine has given up his cabin to the wife of his servant who is in a very reduced state from constant sickness”. On the Randolph, the steerage passengers had a dance on deck with the black cook as the fiddler, and there were strict regulations with regard to cleanliness in the steerage. “ All the men were obliged to be on deck by a quarter before six to wash and the women by a quarter before eight.” On the Sir George Seymour in the tropics “ the emigrants dance in the moonlight every night till half past nine, when they retire and the lights are put out.” Fire was the greatest of all dangers to wooden ships. Two boys, brought up for trial before the Captain and the surgeon for lighting a pipe in the stern of the long boat amongst the hay, were found guilty, but let off on promising to behave better in future. Cyrus’s account of a fire in the after hold; “ The mate gave his orders in the coolest but most distinct manner, and immediately went below. We having so good an example, got the fire and all other buckets in the ship, and formed a double line of the emigrants, and were able to keep up a continuous supply of water to the seamen who alone were allowed to go below. The smoke by this time was pouring up the main hatchway pretty thickly, and the women and children came pouring up from their quarters – most of them in a terrible state. Some gentlemen prevailed on them to go below, and went also to prevent their reappearance. After some half hour of such feelings as no one can imagine who has not stood as we did, over a fire in the close proximity of several barrels of oil spirits and gun-powder, it was declared extinguished.” Both men find the sea and sunsets very beautiful “it altogether the most wonderful appearance I ever saw.” “The beauty of the ocean cannot be described or imagined. Water of the most beautiful blue, broken by crested waves of snowy whiteness. I never could have thought the mere atmospheric enjoyment could have been of so intense a kind; it is a wonderfully dreamy sort of existence.” Dr A.C. Barker “A few nights ago while off Gulf Guinea, the phosphorescence of the sea increased to such a degree that the vessel seemed to plough its way through molten silver; while we were admiring the beauty of the spectacle, we saw it as it were fiery serpents running from under the vessel from all directions and tumbling over each other. They proved to be a herd of dolphins which, disturbing the phosphorescent animalcules as they rushed through them, left long lines of light on their track, while their own bodies were illuminated in the most beautiful manner.” Entertainment A play was performed on board; Cyrus writes “ A theatrical Party is formed today; Captain Dale, Mr Williams and myself were chosen as a Committee of Enquiry and Management – decided to have ‘The Rivals’ by Sheridan; having unfortunately dropped overboard the only copy of Shakespeare we can at present come at. The faces of the party as the book went down were rich in the extreme – particularly the unfortunate wretch who dropped it…. I have a small part – Faulkland.” On the 25th Nov; “The Rivals was acted this evening with great eclat, about 50 people being employed the greater part of the day in making preparations.” C.J.Bridge was prompter and stage manager. He writes; “We were all very busy all day in preparing a theatre for the performance. It was erected between decks and formed a very pretty theatre, and the performance went off very well. After it was all over the stage was cleared away and supper laid out, which was done full justice to. A very convivial evening.” On Nov 7th, the sailors showed signs of mutinous conduct. One was put in irons for refusing to do an extra watch after using abusive language to the chief officer. Then the rest of his watch refused to work unless he was released, and attacked the black cook who was disliked by the sailors. Cyrus writes; “The Captain intervened and was struck; the man who did so being placed also in irons. At 6, when their watch turned out, the man whose turn it was to take the wheel refused to do so. I now went below and got my pistol. Cutlasses and muskets were handed on the poop.” Preparations were made for flogging the man when he fortunately consented to return to his duties, and the rest followed his example. “We are still prepared to go to all lengths to preserve authority on the ship.” Becalmed The wind was necessary for movement, calms leaving sailing ships motionless – and bringing them together. Socialising between vessels becalmed in the doldrums was not infrequent. Boatloads of ladies and gentlemen of the Randolph exchanged visits and dinner with passengers of the French ship Active in September 1850. The French captain at first did not wish to dine aboard the Randolph but in the end yielded to the solicitations of the ladies, who were very anxious to stay. The Lyttelton Times of 11 January 1851, gives an account of the voyages of the First Four Ships, ‘The Randolph becalmed two days in company with a French barque, having on board an operatic company proceeding to the Mauritius. Some of the Randolph’s passengers pulled to the French vessel, and invited a large party to dine with them, and the next day they dined on board the Frenchman. A great deal of Italian music was sung in really first rate style.’ C.J. Bridge writes -A complete calm. A French bark also becalmed about 2 miles off. The Captain gave us permission to have one of the boats out… We went on board where we were received with the greatest politeness. We had rather a difficulty in making ourselves understood as none of us could speak much French, but altogether we managed very well. We persuaded some of the passengers to return with us…we pressed them to dine with us and we had a very good dinner, after which we had some singing. The next day, still no wind. The boat was lowered and off we went to the French ship with a large party including two ladies. We were invited to dine with them and about 4 o’clock we sat down to a very good dinner, served up quite in the French style. We had six courses, soup, preserved meats, preserved woodcocks, asparagus and their wines claret, champagne and Madeira were excellent. Cyrus, who was still on the Sir George Seymour, writes - In the morning a calm. The heat intense, and much languor consequently prevails. Six vessels accompany us at noon. At evening 16 ships all becalmed, in sight from the main top. The next day, there was still a great many ships in sight and immense numbers of porpoises. Charlotte Godley, wife of John Robert Godley, the chief agent for the Canterbury Association writes of her voyage in the Lady Nugent; February, 1850; Becalmed for some time on each side of the line (the equator), and a great deal of society. Twenty-six ships all in sight together from the mast one morning. We spoke to a good many, had two visits ourselves, and one afternoon, some of the young gentlemen went off in a boat, and drank tea in one ship and called on another, and got back soon after dark. Mrs Barker writes “ We are greatly teased with cockroaches as long as your finger but our cats keep ours off.” After their kitten was lost overboard, they had to “lock up poor puss who bears her wretched fate very well considering.” Later “Poor old puss survives in her cage looking hopefully at us when we notice her.” In Christchurch some months later Dr Barker writes “I have been obliged to get a horse and 2 cows. These, together with my terrier and poor old puss, who keeps purring around me and reminding me of old times, form all my live stock excepting my hens, three only having survived the voyage.” As the ships came to the Southern Latitudes, the weather became very cold. Cyrus writes “Captain Dale is of the opinion that we were near some large body of ice” and the seas became mountainous “ A heavy sea which is now thought nothing of, although I believe it would have frightened half of us out of our wits had it occurred the week we left Plymouth.” Arrival in New Zealand As the ship sailed up the East Coast of the South Island (Middle Island then), both men were impressed “ it altogether presented the grandest piece of scenery I ever saw. The air came soft and warm off the land bringing with it a most delightful perfume of the herbage…. The gently swelling hills near the coast are covered with timber and over these, but at great distance, we could catch glimpses of the New Zealand Alps, covered with snow. Their outline seen amidst the clouds was very abrupt and bold. I have never seen before any such mountains… We saw no sign of human habitation. The general appearance of the country is rich and beautifully diversified with hills and dales. When so near shore the warm air came over us and we fancied was full of perfume of shrubs and flowers.” Off Otago they could see smoke from the clearings. Finally at 4pm on the 16th Dec, they saw the heads of Victoria Harbour. “We saw three ships at anchor. At first we thought we were the last ship, but presently made out the blue ensign which told us one was a man-of-war. On we sailed down the noble harbour and as we passed close to the ship, the jolly tars burst out with three right good English cheers. Every soul of us was on deck and were not slow in repeating it and as our anchor went down the other ship whose decks were also crowded paid us the same compliment. God save the Queen was then sung by us in chorus…This ship turned out to be the Charlotte Jane – the mysterious ship which had so many times been seen within the last few days and which had cast anchor that morning at 10.” The other ship was the Fly, with the Governor, Sir George and Lady Grey on board. Edward Ward’s journal: Dec 16th: “I got up early and went on deck to find that we were standing direct for Port Cooper…through high brown hills with not a speck of life upon them to be seen. Till at last we saw a line of road, sloping upwards across one of the hills, and soon specks of labourers could be seen working at this road” (John Macfarlane, grandfather of Hugh, worked on the Sumner road and saw the ships come in to Lyttelton. The Canterbury Association’s lack of funds prevented the completion of this road, the only way over the hills being the Bridle Path, a rough and steep track. John Macfarlane was a pre-Adamite ie a settler who was in Canterbury before the arrival of the ‘Pilgrims’ who were the Canterbury Association settlers). “All our eyes strained to see if any ships were lying there – we at last saw two, and dire was the consternation, for we imagined we must be the third – beaten by two. But one was a ship-of-war and the other too small to be one of ours”. Ward went ashore and “after a toilsome walk looked down upon the plains, and the sea on the other side. “It was magnificent – a vast level, described as rich and fertile land, stretched away to a ridge of grassy hills at the foot of the Snowy Mountains”. He admired a patch of New Zealand bush on the way back down to Lyttelton and returned to the Charlotte Jane. “After dinner a ship was discovered coming in, and lo! It was the Randolph. We gave and received three cheers as she came up alongside…The news from her was that there had been disagreeables on board of all kinds. A mutiny among the sailors – the Captain having had to warn the cuddy passengers. There was also a rumour of pistols among the cabin passengers”. Dec 17th: The Sir George Seymour came in and anchored abreast of us. She had sailed on Sunday the 8th, so that we only beat her in point of time by two hours”. Another Pre-Adamite, William Pratt gives his account of the arrival of the First Four Ships in his book ‘Colonial Experiences’. December 16th, 1850, a glorious New Zealand summer morning…About 10am a large ship, the Charlotte Jane suddenly appeared rounding Officer’s Point. She had not been observed coming up the harbour, and was brought to anchor opposite the town…The Randolph arrived at her anchorage at 3pm the same day, and the Sir George Seymour at 10am on the 17th, the Cressy not putting in an appearance until the 27th. On the 17th I was on board the Randolph when the Sir George Seymour sailed majestically up the harbour and dropped her anchor a short distance from the Randolph. I inquired the special cause of the vociferous cheering on board both vessels, and was told the Randolph folks were welcoming the arrival of a passenger they had lost in mid-ocean, a Mr Davey, who had had the unique experience of coming out in two ships, starting from Plymouth in one and landing at his destination in another without having been shipwrecked. It appeared that on arriving at Plymouth to join his ship he found she had sailed; and as the Sir George Seymour was on the point of starting also for Lyttelton, he jumped on board the latter ship, and during the voyage they sighted the Randolph and it being calm and there being a smooth sea the vessels were enabled to approach near enough together to permit of his being transferred to his own ship. Naturally there was great excitement and commotion in our small township from such an influx of strangers. (Mr Pratt added this last paragraph to his story for the book ‘Canterbury Old and New 18501900, which was published 50 years later for the 50th anniversary of Canterbury. He inadvertently confused the names of the ships. Cyrus left England on the Sir George Seymour and arrived on the Randolph.) Cyrus writes on the 17th; “The Sir George Seymour anchored at 12 and Captain Dale took me with him in his gig (rowing boat) to pay our respects to the Captain and passengers. Our meeting was a very pleasant one and numerous were the congratulations on either side.” Charlotte Godley writes; “ON MONDAY THE 16TH DECEMBER (I don’t know how to write large enough letters for the event), in the morning a ship was announced early, in sight, and then at anchor. But there is a point of rock which hides them from our view. Then my husband encountered Mr Fitzgerald, who was the first to step ashore, in the road down to the jetty. ‘It never rains but it pours’ is a very old saying, and in the evening of the same day the Randolph anchored by the side of the Charlotte Jane, just as many hours after her, as she had left Plymouth. We were full of wonder, and already thought it a remarkable coincidence, when next morning in came the Sir George Seymour, making the third ship that had performed the voyage in such an unusually short time, for she had started twelve hours after the Randolph; was it not most curious? One passenger, too, who had taken his place by the Randolph, was a little late at Plymouth, and had to follow in the Sir George; the ships spoke during the calms at the line, and the Randolph passenger was transferred to his own ship, and still they all got here in the order in which they started.” Sir Henry Brett writes in 1928 “ Although they were by no means superstitious the Canterbury pioneers were very much impressed by the fact that three of the First Four Ships arrived in Lyttelton within a few hours of each other, and the fourth arrived only ten days later. With the exception of a meeting between the Randolph and the Sir George Seymour none of the ships had seen one another from the day they left Plymouth Sound, and yet they converged on their appointed haven with almost the unanimity of birds coming home at night. There were very few people who did not take this unusual happening as a good omen.” The Randolph beat the Sir George Seymour into Lyttelton by nearly a day, arriving on Monday 16th December; she was the second of the four ships to arrive –the Charlotte Jane having arrived earlier the same day. Of those four historic ships, the Charlotte Jane left Plymouth on the evening of September 7th 1850 (thus not clearing Plymouth Sound until after midnight which counted as starting on September 8th), the other three on September 8th 1850. The Charlotte Jane and the Randolph arrived on December 16th, The Sir George Seymour on December 17th, and the Cressy on December 27th, their almost simultaneous appearance in New Zealand waters proving a record for Canterbury. The Charlotte Jane and the Randolph took 99 days, and the Sir George Seymour just on 100 days from port to port. Cyrus’s 98-day passage was said to be a record for several years. When the First Four Ships arrived, something like 1,000 “pre-Adamite’ migrants had already come to Canterbury. In the first nine months of organized settlement the Canterbury Association dispatched sixteen ships carrying 2,500 people. John Robert Godley, known as the ‘Founder of Canterbury’ was the leader of the new colony and arrived in Lyttelton 6 months before the First Four Ships (although on this visit he only stayed for 24 hours before leaving for Wellington where he felt he was in a better position to “acquire general information”). He writes “Halfway up the harbour we passed a whale-boat, which informed us that we might go up and anchor opposite ‘the town’. At that time we had seen no sign of civilization, except the line of a road in process of formation over the top of the hill on the northern shore, and no human habitation, except some Maori huts close to the beach; but we held on. On rounding the bluff … I was perfectly astounded with what I saw. One might have supposed that the country had been colonized for years, so settled and busy was the look of its port. There is a jetty; from thence a wide road leads up the hill, and turns off to the east. On each side of the road there are houses scattered to the number of about 25, including two hotels and a custom-house. A stately edifice was introduced in due form to us as ‘our house’. It is weather-boarded, has six very goodsized rooms and a veranda.” Port Cooper was the name given to Lyttelton Harbour about 1828 by Captain William Wiseman, a flax trader from Sydney, while Port Victoria was the name chosen by the Canterbury Association; the Pilgrims, however found it easier to refer to the township Lyttelton on the shores of Lyttelton Harbour. The day after arriving Cyrus writes; “I then went on shore and looked over the site of the town which is limited in extent and fit only for the Port. There is however an excellent jetty and road partly finished for about 4 miles over the hills to the town of Sumner. There are 30 to 40 houses at the Port of all styles of architecture from the mud hut to the wooden house. A bridle road is also being carried over the hills to the Dean’s Farm at Riccarton. I went up this road and took my first view of the plains stretching away as far as the eye can reach to Double Corner and the Snowy Mountains.” A fellow colonist sounds more enthusiastic. Five weeks after arriving he writes in a letter about going ashore with a friend and Crib (his dog?) “No one was wilder with joy at touching land again than Crib; he raced about us as if he had been mad. We were in such a state of excitement that we could observe very little. We were put ashore at the steps of a handsome jetty of wood… We made for the top of the hill which separates the town from the plain. We went up the steep path mad with excitement, hurrahing at every new flower, plant or insect which we saw. Crib had his share of this fun, for he kept perpetually chasing the little lizards which crawl in numbers over the ground. At the top of the hills we had our first view of our magnificent plains – the beautiful little bay of Lyttelton on one side, and the grand plain, with forty miles of surfy beach on the other. Two or three ranges of mountains, and the whole backed by the high, majestic range of the Southern Alps were the extent of this view. The air here is so transparent, that distances cannot be guessed by an eye accustomed to English scenery. “After taking a rest from the boiling heat, we descended by another path through the wood which backs the town. The growth of underwood is the great feature. The space between the trees is crowded with the most beautiful of the rhododendron appearance – I mean in leaf alone, for none were then in flower…These were matted together with clematis, which grows to an immense height with a whole umbrella-crown of sweet blossoms. Added to these sights and smells were the sounds of singing-birds, new, fresh and sweet – especially the tui. Nothing, not even the nightingale, can approach the sweetness of this tui when he sings his own song… We are all as happy and comfortable as we could ever have expected to be. Speaking for myself, I never pine at all for home, seldom, indeed, thinking of it except on Sundays.” Two days after arriving Cyrus called on Captain Thomas and presented his letters of introduction. “I then started for the Dean’s Farm across the plains, with a party. It is about 10 miles. There is a sort of a footpath, which may easily be followed. On our way we recognized many English wild flowers and great quantities of the Sow Thistle. The towai towai grass and flax plants were in many places over our heads. On our way we encountered a party of the natives from the interior coming in to see the Governor. They were many of them arrayed in the red blanket and carrying their spears and axes, and some much tattooed. They appeared to be pleased to see us and opened a parley, produced tobacco and were soon best of friends. We were most hospitably received by the Messrs. Deans as some of the party had letters of introduction to them. We had for dinner a fine saddle of mutton, beautiful bread, cheese and butter. In the garden we saw peach trees covered with fruit, plums and cherries, beautiful apples, currants and gooseberries. They gave a very favourable account of the climate which, from all I have seen, is certainly very fine; and say they would not return to England on any consideration [Scotland was the Deans’ homeland]. On our return three of our party were laid up, and encamped on the plain, covering themselves with fern, being too much tired to proceed any further. I am pleased with what I have seen.” For the first few days, Cyrus stayed on board the Randolph. th 19 December; “In the evening went on shore again and walked up the new road.” 20th Dec; “Copying map of New Zealand for Mr Scott; could not walk, having rubbed my heel. Our seamen have all struck, and three of them are in confinement. Sent home letters via Wellington.” 21st Dec; “Went to Mr Godley’s office, and was engaged by Captain Thomas to make tracings for the lithographer, of part of Canterbury plains.” Sunday 22nd; “Attended divine service at the store. In the afternoon went to Quail Island. We only saw two quails.” 23rd Dec; “Went on shore early, breakfasted with Capt. Thomas and then to the office. Drawing map of Lyttelton for Mr Brittan. People very busy in all directions putting up various kinds of houses.” Cyrus’s journal of the voyage “gives the impression of a man susceptible to the beauties of nature, friendly and good natured; the journal contains not a word critical of anyone on board.” When Emma Mortimer came out in the Ashmore in 1854, she was escorted by the newly-married C. J. Bridges. Mary Anne Davie, Cyrus’s sister accompanied her. The Ashmore was bound for Nelson; there was a mutiny and she was delayed there. Cyrus makes no mention of Emma in his journal until the last line “Friday 14th Feb. Fourth letter to Emma, by Gale.” Henry Sewell writes in late 1854 “No ships, no letters – and we are lying in a state of miserable stagnation until the steamer (from Wellington) arrives. The Ashmore ought to be here but the last that was heard of her was that she had lost all hands at Nelson.” Like many rumours, this one was as untrue as it was gloomy. Four days later the Ashmore sailed into Lyttelton Harbour and Sewell wrote of his joy at receiving mail from home. It is not recorded what Cyrus thought either before or after the Ashmore arrived carrying Emma whom he had not seen for more than four years. The Deans brothers of Riccarton, William and John were the first Europeans to settle on the Canterbury plains, arriving here in 1843. They named the river Avon after a stream near their home in Scotland. John Deans writes to his father in February 1851 of the Canterbury ships “ the arrival of these ships all full of passengers has caused a great stir here, and we can no longer complain of the want of neighbours. There are more ships on their way out, on their arrival we will number more than 2,000 souls. The settlers are generally very well pleased with their new home, and I think are as good a collection as came to any of the other settlements; there are a few of higher standing than any who had previously immigrated to New Zealand. We of course have had a great many visitors, as almost everyone comes to see our crops and garden.” From a tract published by the Society of Canterbury Colonists in 1850; “Brief Information about the Canterbury Colonists” The founders of the colony are the Canterbury Association. Their object is ‘founding the settlement of Canterbury in New Zealand.’ The site is a territory on the east coast of the Middle Island, consisting of grassy plains, intersected by several rivers, running to the sea from an Alpine chain of snow-capped mountains. Near the middle of the coast line, Banks Peninsula contains two lake-like harbours. The temperature corresponds with that of the most pleasant spots in the south of France. The climate is remarkable for warmth without sultriness, freshness without cold, and a clear brightness without aridity. The scenery is very beautiful and in some places magnificent. The fertility of the soil has been abundantly proved by the experience of successful squatters. Drought is unknown. As respects flowers, kitchen vegetables and all the English fruits, the gardens of the French settlers at Akaroa, and of the squatters on Sumner plain [the Deans] are described as teeming with produce of the finest quality. Sea fish is abundant and of excellent quality. The only wild quadruped is swine: they are numerous, are very good to eat, and afford plenty of hard sport. There are no snakes, wild dogs, or other indigenous vermin. A practical aim of the Founders has been to make their settlement differ from others, in being, more fully than in any previous case, an extension of England with regard to the more refined attributes of civilization. When there is an emigration of the higher and richer classes to any colony, there is sure to be one of the labouring classes because the latter know that those who have been favoured at home as respects property, education and social position, will not emigrate at all unless they are attracted to the colony by a reasonable certainty of doing well there… C.E.Carrington writes in ‘John Robert Godley of Canterbury’, 1950; Sir Cracroft Wilson, an Indian civilian who visited Canterbury in 1854, and made up his mind to settle there, described the Pilgrims as ‘poor, proud, pious and without servants’. By 1858 there was no doubt that Canterbury settlement was flourishing. There was no previous example in the history of the British Empire of an agricultural colony that was selfsupporting in its third year, free of debt in its sixth year, and which enjoyed a favourable balance of trade in its eighth year. Life in Canterbury Four days after arriving, Cyrus, who was educated and trained in England as a surveyor and engineer, was signed up by Captain Thomas to work on maps for £300 a year; he took possession of a loft over Godley’s office. Cyrus’s brother, William, who came to New Zealand from America in 1864, was also a surveyor. This occupation has continued down the family through Frank, his son Lewis to his son Michael and sons-in-law, and cousin Dick Brittan. (Davie, Lovell-Smith is a wellknown Christchurch surveying firm). Cyrus gained a reputation as a tireless walker. On Xmas Day he writes, “All the Randolph passengers without any exception returned on board the Randolph and had dinner in old English style. After dinner a handsome testimonial was handed to the Captain, signed by all. This is our last night on the ship or at all events the last time we can all expect to meet again. I leave the gallant Randolph with more reluctance than ever I quitted any house on shore. We have been fortunate indeed both in our captain and voyage.” 28th Dec; “In evening went to Captain Thomases who is burnt out of his home and now living at the store in a room about 20 by 12 with a fireplace and chimney in the centre. I found there Mr Wakefield and Gardiner, and spent a very pleasant evening. We had a little fire which is always pleasant here of an evening in a single boarded house through which the wind whistles. The different kinds of temporary houses here are very amusing but in this fine climate a gipsy life is very amusing”. The settlers had yet to experience their first southerly. At first Cyrus worked on maps of the Mandeville and Christchurch districts, and on plans of Christchurch and Lyttelton lots. On the 2nd January he walked with Mr Godley to view the boundary of town land for college. 3rd January; “In the evening walking down to the quay, observed the ensigns being run up on all the ships and heard tremendous cheering on board. In a few minutes a schooner yacht the Undine, with the Episcopal flag of New Zealand, rounded the Point and dropped the anchor. I formed one of the amateur crew of gentlemen who rowed out Mr Young the Clergyman, to pay his respects to the Bishop. We all had the honour of being introduced to his Lordship who heard at Wellington of my adventure in the two ships. We all joined in the evening prayers in the little cabin, and then took our leave much pleased with our reception.” The next day “Dr Selwyn has been on shore all day, sometimes standing in a group of natives who would keep him by the hour. In the evening he visited our tents, and talked with us for some time. He is most anxious that we should not separate too widely. I have joined a party of three. We have a servant of one of the party to cook for us, which is sometimes performed by suspending the boiler from a triangle of three sticks over a hole in the ground – sometimes at the cooking house in the Barracks. We find this method of living very pleasant and inexpensive. I still retain my loft to sleep in.” On the 8th he went to live with Bridge and Lee in a tent. 20th January; “Received letter from Mr Godley of Capt. Thomas’ retirement and of Mr Cass’ appointment to be Chief Surveyor. Mr Cass came to me and informed me that they had determined my salary at £20 per month.” 24th January; “Sent second letter to John by Cressy.” (brother John Eveleigh Davie?) 7 Feb; “The Castle Eden arrived – had letters.”