Child Social Emotional Development

advertisement

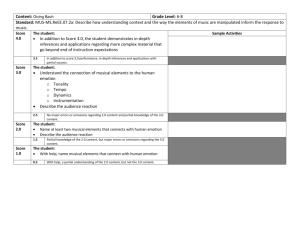

The effect of musical activities on children’s social emotional development (SED) Teena Sim, Univeriti Putra Malaysia INTRODUCTION Story About a Shy Boy; One little shy boy came into my music class 2 years ago, avoided eye contact when I greeted him and his mother, stayed close to his mother and refused to participate in most of the activities throughout the class even though his eyes glowed with enthusiasm when the instruments were given out. This was not the first time that I had shy child like him before, and knowing that he needed more time to adapt to the environment before he could join any of the activities, I kept myself a few steps away from him when conducting the class. At the end of the class, all the other children’s singing and dancing moved him; he joined in the circle although without holding others’ hands. This scenario continued for a couple of months with him getting a little closer to me each time. He started to give me a hug after class on the third month that showed his comfort and security in the class. I was very excited about his building confidence but the mother looked very worried and insisted he had learnt nothing if he was not participating. On the sixth month, I finally decided to invite him to come in the class without his mother as all the other children were in the class without adult company. I was extremely happy when he joined in the group and danced cheerfully and played his favorite instrument alone while I sang. The above mentioned scenario lead to one question that reflecting the need of initiating this research was: what does musical activities bring to a child’s social emotional development? Author met children from different backgrounds and with distinct characters that were referred as different temperaments in this study and witness the effect of musical activities on each individual. Children of different temperaments respond to musical activities in a varied way and receive different level of impact on social emotional development. For example, a positive and easy child greets friends with smiles and participates in most activities enthusiastically and progresses smoothly towards expected goals whereas a negative, moody and difficult child will either totally withdraw themselves in the beginning or behave aggressively and show his /her progress in an uncertain manner. It might take different quantity of duration for the child learning to adjust their emotional state through musical activities participation. However participating in musical activities seems able to facilitate a child to a comfortable level of intensity in order to be productively engaged in their surroundings. Musical activities therefore predicted as an effective tool to enhance children social emotional development in this study. Research Hypothesis Author presents a concept of the relationships among musical activities, temperament and social emotional development. It is proposed that a consistent, well planned musical activities may bring a positive effect on children’s social emotional development regardless of their unique temperament. To examine the relationships between the variables, the following null hypotheses were formed: Ho 1 There is no significant difference between the pre and post score of social emotional development (SED). Ho 2 There is no significant difference between the improvement levels in social emotional development by temperament. Framework Social emotional development is like any other perspective of development. Like cognitive or physical development, it is a learning path; it is the way a child learns how to interpret his/her surroundings and learn how to develop his/her abilities of emotional expression, understanding and regulation. With his/her distinctive nature (Temperament), his/her distinctive way of interactive exploring, and equal weight of the environmental role (through well plan musical activities), he/her then become a distinctive adult; prosaically or antisocially (Figure 1.1). Independent Intervention Dependent Variable Musical Social Emotional Activities Development Variable Temperament Figure 1.1 Framework of the study In this study, musical activities in a group is assumed to be an effective media for helping children to increase their ability in understanding, regulation and expressing their social emotion even it might have a different degree of effect on children with different temperament. LITERATURE REVIEW Humans are a very social & expressive species. Social emotions play a critical part in our daily life, they even override our most basic needs; fear can forestall our appetite, anxiety can lead to a student’s poor performance in an examination, anger can cause a person to hurt others, and joy can cause one to be more generous (Berk, 2005). During the early childhood, social emotional development sets the stage for exploration and later readiness to learn and indeed, is the foundation for all development (Jerald, Cohen & Stark, 2000, Bagdi 2005). Researches support that music is a wonderful art form that encompasses all areas of child development, namely emotional, intellectual, physical, moral, and aesthetics in a delightful and enjoyable way. In a study of the extra musical effects of music lessons on preschoolers, Devries (2004) concluded that six themes addressed the extra musical effect of music lessons: 1) involvement in music activities allowed children to release energy; 2) engagement in music-movement activities developed motor skills in children; 3) a variety of music activities promoted opportunities for student socialization; 4) music activities provided opportunities for children to express themselves; 5) music contributed to sociodramatic play; and 6) music listening activities focused children's listening skills. Music provides an opportunity for children to participate on a social level through group activities. This helped the development of prosocial skills and improves self-esteem (Doise, Mugny, & Perret-Clermont, 1975; Johnson & Johnson, 1989; Light & Glachan, 1985; Roazzi & Bryant, 1998, Davidson, 2003). Involving in musical activities will increase children’s social emotional sensitivity (Weinberger, 2001). However children are born with each unique behavior style. Beginning in 1956, Thomas and Chess collected enormous amounts of data on childrearing practices and behaviors among 138 middle-class white children and 95 lower-socioeconomic-class Puerto Rican children, from infancy to 7 or 8 years of age. Analysis yielded nine categories of "behavioral style": (1) general activity level, (2) regularity and predictability of basic functions, like hunger, sleep, and elimination, (3) initial reaction to unfamiliarity, especially approach and withdrawal, (4) ease of adaptation to new situations (obviously correlated with the third category), (5) responsiveness to subtle stimulus events, (6) amount of energy associated with activity, (7) dominant mood, primary whether happy or irritably, (8) distractibility, and (9) attention span and persistence. Several studies have shown that individual differences in temperament qualities, such as activity level or approach/withdrawal, may be related to children's social functioning and adjustment within the peer group, the responses they make to their peers and the quality of their relationships with other children (Farver & Branstetter, 1994; Keogh & Burstein, 1988; Mobley & Pullis, 1991; Stocker & Dunn, 1990). In general, children with easy temperaments, defined as approachful, adaptive and positive in mood (Thomas & Chess, 1977) have been found to respond prosocially to peer distress (Farver & Branstetter, 1994), and are rated as behaviorally adjusted to the preschool environment in terms of cooperation and persistence (Mobley & Pullis, 1991). In contrast, children with difficult temperaments appear to have relationships that are more problematic with their peers and are more likely to exhibit socialization and behavioral problems (Kym Irving, 2001). Musical activities are of the utmost importance when present as a mediator, catalyst, moderator, and enhancer in a child’s development holistically. However, there is no research on how musical activities affect children’s social emotional development of different types of temperaments. This might be because musical activities were used by psychologist for behavior disorder or special children in a therapeutic effect or by early childhood music educators in upgrading children’s musicality or lastly might be missed by author’s searching. METHOLOGY Study Design This research was a naturalistic observational study conducted (1) in the homes by the parents to assess the child’s temperament and (2) in the music classroom by the researcher to assess the child’s social emotional development. Subjects were recruited through convenience sampling where all the children who attended the on going music class (from 5 months to 40 months of participation history) weekly in two music centers (Kajang and Sunway) conducted by the researcher. Location of study The research was carried out in Bandar Sunway, and Kajang that comprises of huge housing estates which is multiracial and predominantly occupied by middle-income family. Sampling A sample size of 42 preschool children that represented a cohort of preschool children from the age of 5-6 years old (14 boys, 28 girls; 22 five years, 20 six years old as illustrated in Table 1) participated for the study. 74% were Chinese, 19% were Indian, and 7% were Malay. Most children have siblings: 45% has two, 33% has three, 10% has four and 10% was a single child and 2 % from a big family of seven, most children i.e. 64% were first child, and second child occupied 26%. All the children had at least two months old of musical activities exposure before the observation started. Table 1: Composition of the subjects and background information (n=42) Gender Boy Girl N 14 28 % 33.3% 66.7% Age 5 6 22 20 52.4% 47.6% Race Chinese Others 30 11 73.8% 26.2% No of siblings 1 2 3 4 7 4 19 13 4 1 9.5% 45.2% 33.3% 9.5% 2.5% Birth of order 1 26 64.3% Stay with Grandparents 2 Others 11 4 26.2% 9.5% Yes No 18 24 42.9% 57.1% As all subjects are recruited through convenient sample, therefore the number of each temperament type was uneven as depicted in Figure 1. 10 Temperament Difficult Slow To Warm Up 6 9 4 5 2 3 1 1 Age Group 0 Easy 6 Years Old Count 8 1 10 5 Years Old Count 8 6 4 2 4 3 4 5 4 2 0 boy girl Child's Gender Figure 1 Distribution of subjects by age, gender and temperament Procedure A briefing on the purpose and the details of the study was given to the parents. At the end of the briefing, the Carey Temperament Scale was distributed to the parents. The Carey Temperament Scale was in three languages (English, Chinese and Bahasa Malaysia). Parents were given a choice of selecting the version they were most competent in. Once the Carey Temperament was distributed to the parents, a one-month’s observation of the children’s behavior during the one-hour weekly music class (as described in intervention program, ) i.e. a total of 4 to 5 hours observation of the child’s behavior when participating in the musical activities was conducted before the researcher filled in the first Social Emotional Developmental Checklist (pre-test). The second Social Emotional Developmental Checklist was filled six months later after another month of observation on children’s behavior in participating the musical activities. Instruments Two forms of instruments used in this study, consisted of questionnaires (set A and B) and intervention programs (type I and II). SET A: Child Social Emotional Development This measure comprised of 60 items, which incorporated children’s emotional regulation and maturity, social skills and awareness as well as their prosocial versus aggressive tendencies. The internal reliability for social emotional development was 0.929 (pre) and 0.893 (post) for Petaling Jaya and Kajang (West Malaysia) and 0.83 for Sarawak, East Malaysia (Abdullah & Teena, 2005). The items in the checklist were rated 0 to 2, where 0 was never, 1 was sometimes and 2 was almost always. The Range of possible score was ranging from 0 to 120. There are 31 items accounted for positive social emotional development (known as PSED) that were subdivided into 3 categories as emotional positivity, emotional understanding and interpersonal relationship. Another 29 items accounted for negative social emotional development known as NSED) which were subdivided into 2 categories as external emotional problem and internal emotional problem. The cutoff score of PSED is 24 or greater to take as an indication for social emotional maturation at age 5 and 6 and a total score of 23 or greater for NSED is taken as an indication of risk in psychosocial impairment. However, the scores of NSED were recoded into positive value for overall impression on children’s social emotional development (known as SED) where the cutoff score is 48 or greater to show an indication of the achievement in social emotional developmental milestone for children of age 5 to 6. SET B: The Carey Temperament Scale The Carey Temperament Scales was used to gauge parents’ perception of their children’s behavioral style by using a 6 points Likert scale from 1 was almost never, 2 was rarely, 3 was variable, usually does not, 4 was variable usually does, 5 was frequently and 6 was almost always. The Carey Scales comprised one hundred questions on each child’s activity level, rhythmicity, approachability, adaptability, intensity in a response, mood, persistence, distractibility, threshold and ten question of general impression of child’s temperament from the parents. This questionnaire attached a cover page to obtain a clearer picture on each child’s family background and minimum growing environment. The internal reliability for appraisal of parents’ perception of child’s behavioral style was 0.864 for Petaling Jaya and Kajang (West Malaysia) and 0.909 for Sarawak, East Malaysia (Abdullah & Teena, 2005). For study purposes, the children’s temperament was assigned to three constellations; (1) difficult, (2) slow-to-warm-up (recognized as STWU), and (3) easy (Sean, 2002). Intervention Programs The music class was conducted in a group of five to ten children. There are six groups (four from Type I and two from Type II) with a mixture of children in age four to five, five to six, and six to seven at two different musical programs, which were: Type I (Music & Movement with Percussion Instrument), and Type II (Children Musician Course with Keyboard) The contents of the musical activities in Type I and II program were in six subjects that combined listening, singing, moving, instruments playing, dancing and reading in a delightful musical way. Classroom environment and material in both musical programs were child-centered and the teacher was well equipped with understanding of Early Childhood Development and Temperament. The 2 musical programs were different in approach; Type I, was focusing on all aspects of a child development, such as helping children develop body control (physical), encouraging play, imagination and creativity, encouraging language (cognitive) and communication which laid a foundation for positive self-esteem, disciplining to encourage emotion regulation, morality, and a sense of conscience (social emotion) through musical activities. Type II, on the other hand, concentrated mostly in children’s musical ability development. Analysis and Discussion Improvement of subjects’ social emotional development Paired Samples t-test reveals that there was a significant difference of percentage in improvement of Social emotional development between pre and posttest (t=-13.81, p < .05). Table 2 showed that the pretest of subjects’ SED (n=80.82,) improved significantly (posttest: n=102.31,) after 6 months of musical activities’ participation. It also showed a closer gap of the score from pretest (SD=15.03) to posttest (SD=9.67) which persisted that subjects of wider range of SED level improved in varied pace and reached a closer SED level. The result seems to support findings of research by which showed that active music making brought about better-adjusted social behaviors (Boswell, 1985 and Stanley, 1996) and encouraged positive social emotional development (Forrai, 1997, Berman, 2003). Table 2: Paired Samples Statistic of pre and post SED (n=39) Pair 1 Pre Social Emotional Development Post Social Emotional Development Mean Std. Deviation t –score Sig. (2tailed) 80.82 15.026- -13.814 .000 102.31 9.669 Improvement level of subjects’ social emotional development by different temperament All subjects from either temperament constellations showed significant improvement in SED after six months of musical activities’ participation as in Figure 2 and Table 3. Difficult 105.00 Slow-To-Warm-Up Easy 100.00 Mean 95.00 90.00 85.00 80.00 75.00 Pre score of SED Post score of SED Pre and post test of SED Figure 2: The pre and post score of SED by temperament Table 3 Mean of Pre and Post SED by three temperaments N Temperament Difficult Mean Std Deviation Min ~Max 12 Pre 76.7 Post 101.8 Pre 17.8 Post 9.7 Pre 48~108 Post 85~118 STWU 11 83 100 12.2 11.4 40~102 78~115 Easy 19 101.8 103.9 12.23 8.9 62~110 82~116 Figure 3a showed that difficult category improved the most at 21%, followed by easy category improved 17% and STWU improved 16%. Mean Percentage in Improvement of SED 25.00 20.00 15.00 10.00 21 16 17 5.00 0.00 Difficult Slow To Warm Up Easy Temperament Figure 3a: The mean percentage in improvement of SED by Temperament In Figure 3b, it showed that through musical activities in group, all subjects with three temperament constellations improved the most in intrapersonal relationship. Percentage in Improvement of Emotional Positivity 25.00 Percentage in Improvement of Emotional Understanding Percentage in Improvement of Intrapersonal Relationship Percentage in Improvement of External Emotional Problem 20.00 Percentage in Improvement of internal Emotional Problem Mean 15.00 24 23 22 22 20 10.00 19 19 17 16 16 16 14 12 12 12 5.00 0.00 Difficult Slow To Warm Up Easy Temperament Figure 3b: The mean percentage in improvement of SED (5 components) by Temperament According to Figure 4, among 3 temperamental types, difficult type had generally improved more in both age and gender difference, nevertheless, 5 years old boys of slowto-warm-up improved the most at 24% followed by both 5 and 6 years old boys of difficult category at 23%. Both 5 and 6 years old girls of slow-to-warm-up had the least improvement at 11%. For comparison purposes, the groups’ improvements were ranked as in Table 4. Mean Percentage i... 17 0.00 25.00 20.00 15.00 23 18 5.00 17 Age Group 10.00 5 Years Old 11 5.00 6 Years Old 22 Child's Gender 10.00 Child's Gender Mean Percentage i... 15.00 boy 0.00 25.00 20.00 15.00 10.00 5.00 girl Mean Percentage i... 20.00 girl 17 11 16 0.00 25.00 20.00 15.00 10.00 23 24 Difficult Slow To Warm Up 20 boy Mean Percentage i... 25.00 5.00 0.00 Easy Temperament Figure 4. The comparisons of SED improvement in the percentages by Age, Gender and temperament The reasons why difficult temperament, 5 years old girls and boys improved more than the other was assumed that musical activities worked well to improve their SED since they have more rooms to be improved. To summarize the above result, this study asserted that with musical activities’ participation, all categories of children gained the benefits of improvement in their social emotional development especially the 5 years old boys of STWU temperament who had shown the most significant improvement. Based on the temperamental categorizing of Carey Temperament Scales, the definition of STWU in this study is children who are inactive, withdrawing, non-adaptable, with mild intensity, and negative mood. By using musical activities as a medium, the joyous, conducive atmosphere and appealing “leadership” of the easy children and an understanding teacher, the group may simply attract those inactive and withdrawing children to participate. Some withdrawing children may not join in the first few classes, but with consistent exposure and witnessing the scene of other children enjoying the activities, the withdrawing children will eventually join in the group and open themselves to the others, though different case might take different period of time to initiate the first move. This is true especially when it come to the different gender where boys will be attracted more easily to participate than the girls that explained the above result. Due to the temperamental characteristic, this group of subjects somehow shows a general small degree of improvement after 6 months of musical activities’ participation. Table 4 Ranking of the improvement in SED Improvement Age No Gender Temperament 24% 5 3 Boys STWU 23% 5&6 4 Boys Difficult 22% 6 3 Girls Difficult 20% 5 4 Boys Easy 18% 6 1 Boys STWU 17% 5 4 Girls Difficult 6 10 Boys & Girls Easy 16% 5 5 Girls Easy 11% 5&6 7 Girls STWU Children in difficult temperament in this study were categorized as children with arrhythmic, withdrawing, non-adaptable, negative mood but respond with intensive emotion. They could not express themselves well and understand others precisely, could be violent to the others, behaved uncooperative and moody. Musical activities helped these children to out pour their expression through movement and instrument playing and sooth them through singing or holding hands with others in circle games. According to the result, no extreme difference was shown between the improvement of boys and girls as basically they are both active so it is easier to invite them to the participation, but most significant improvement was found among these groups of subjects. Children in easy temperament are rhythmic, approaching, adaptable, mild intensity and positive mood that always been responding positively. There is no significant difference among the easy temperament of different age and gender was shown in the result implied the fact that easy temperament children participated and enjoy group activities easily and improved almost in the same rate. However, Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance revealed that there was no significant difference in the improvement of SED between the three constellations of temperament (Table 5). This finding does not support results of previous studies that indicated that there were differences in the social emotional responses of children of different temperament. This study assumed that other factor like the type of music program, duration of musical activities’ participation might account for bringing the subjects grow to the similar social emotional level. Table 5 Repeated Measures ANOVA between the differences of pre and post score of subjects’ SED by temperament (n=39) Type III Sum of Source Mean Squares Df Square F Sig. Within-Subjects Contrasts factor1 factor1 * Temperament Error(factor1) 8460.748 1 8460.748 181.676 .000 116.328 2 58.164 1.249 .299 1676.543 36 46.571 Between-Subjects Contrasts Intercept 606634.26 5 Temperament Error 1 606634.265 257.727 2 128.863 10081.453 36 280.040 2166.23 9 .460 .000 .635 CONCLUSION The present observation examined how much consistent weekly musical activities can improve the social emotional development of 5 and 6 years old young children with different temperament. Two hypotheses were formed to examine the different levels of improvement in subjects’ social emotional development by temperament. The conclusions were drawn as follow; Ho 1 There is no significant difference between the pre and post score of children’s social emotional development. Reject the null hypothesis. There was a significant difference between pre and post score of children’s social emotional development (t =-13.8, p < 0.05). The result seems to support findings of research by which showed that active music making brought about better-adjusted social behaviors (Boswell, 1985 and Stanley, 1996) and encouraged positive social emotional development (Forrai, 1997, Berman, 2003). Ho 2 There is no significant difference between the improvement levels of social emotional development by temperament. Failed to reject the null hypothesis. There was no significant relationship between child’s temperaments with social emotional development. With an appropriate approach and intervention; such as Scaffolding, as well as Goodness of fit seemed to play a major role in improving subject’s social emotional development. The findings to data provide solid support for the claim that participating in consistent weekly musical activities improves 5 and 6 years old young children’s social emotional development regardless of their temperament constellation. The improvement varied from 3.3% to 36.7% (mean=17.9, Std. Deviation=8.1) and none of the tested components (emotional understanding—18.9%, emotional positivity—16.1%, interpersonal relationship—22.2%, external emotional problem—14.5% and internal emotional problem—15.8%) had shown no improvement after at least six months of musical activities’ participation. In short, well planned musical activities with focusing on children’s all facets of development is effective when used as a medium to help improve the subjects’ learning in musicality and as well as the social emotional development. IMPLICATION This study showed subjects learn to understand emotion, learn to respond positively and mostly, learn to cooperate with less aggressive and withdrawal behaviors during participating the musical activities. Music is a medium; teacher sang in a happy tone, subjects cheered, teacher sang sorrowfully, subjects frowned. During the musical activities, subjects cultivated habit of treating peers and instruments in respect, learnt to know how to achieve full enjoyment only by working cooperatively with peers, learnt to manage feeling like anger or fear, learnt to resolve conflicts when fighting for the same instrument, handling stress by music movement, learnt when and how to lead and follow, learnt to differentiate good and bad behavior. Moreover subjects with aggressive tendency learnt to interact with peers in an acceptable way and subjects who were withdrawal nurtured to accept new friends. The emotional foundation at this stage is the readiness for subjects to challenge an even bigger circle—school. In reviewing the beliefs of this study, children’s social emotional development is assumed to be the most important facet; with a healthy social emotional development, children are motivated to explore and ready to learn. On the other hand, music is assumed to be the most appropriate medium in all children activities; it catches children’s attention easily, it pacifies children effectively, it enhances children’s learning joyfully. Therefore well-planned musical activities equipped with teachers in positive attitude and warm personality should be implied to all preschools and daycares so that it benefits all Malaysia children. References Berk L.E. (2005) Child development, seventh edition. Massachusetts: Allyn and Bacon. Boyd J., Barnett W. S., Bodrova E., Leong D. J, and Gomby D. (March 2005). Creative Movement: Delighting in the Child's World. NIEER Policy Report Boyd K, Chalk M, & Law J. (2006) Promoting Children's Social and Emotional Development Through Preschool. Preschool Policy Brief. www.nieer.org Carey W.B. (1997). Understand your child’s temperament. New York: Macmillan Inc. Campell D. (2000). Does music really affect the development of children? WebMD Live Event Transcript, 09/11/2000.www.medicinenet.com Chamberlin J.(2003). Are there hidden benefits to music lessons? 34(9), October 2003 of APA online.http://www.apa.org/monitor/oct03/lessons.html Chess S. and Thomas A. (1996). Temperament theory and practice. New York: Brunner/Mazel Inc. Ciares J. and Borgese P. (2002), The benefits of music on child development. http://www.paulborgese.com Devries P. (2004). The Extramusical Effects of Music Lessons on Preschoolers. Australian Journal of Early Childhood. 29(2), 6+. Field A. (2003). Discovering statistics using SPSS for Windows. SAGE publications. London. Granholm J.M.,Olszewski J.(2003 December ) Social-Emotional Development in Young Children. Michigan Department of Community Health. www.michigan.gov/mdch Kim, Cw (2004 August 1). Nurturing students through group lessons. American Music Teacher. Mary Stouffer (1994) Emotional Growth Through Musical Play. Canadian Child Care Federation. Pageais M (1997). The power of music in communication and development of the child. 22nd International Montessori Congress Suthers L. (2005). Music Experiences for Toddlers in Day Care Centers. Australian Journal of Early Childhood. 29(4). Truglio, R. T. (2001 January 1) Developing minds with music and art. Playthings Vasta R., Miller S.A., Ellis S. (2004). Child psychology. 334-368. John Wiley and son Inc, Hoboken NJ, Weinberger N. M. (1995) The nonmusical outcomes of music education. MuSICA Research Notes. II (2), Fall. Weinberger N. M. (1998) Understanding Music's Emotional Power. MuSICA Research Notes. V (2), Spring. Weinberger N. M. (2001) Feel the Music!! MuSICA Research Notes VIII (1), Winter. Weinberger N.M. (1998). Creating Creativity With Music. MuSICA Research Notes V (12) Spring 1998. Website Music and Emotion: A selected bibliography. http://www.music-cog.ohio-state.edu Nebraska Early Childhood Mental Health Work Group (2001).Understand Young Children’s Mental Health: A Framework for assessment and support of SocialEmotional-Behavior Health. Observing Emotional Development, http://www.newchildcare.co.uk Ways music can benefit the development of children; what had been said and who said it. http://www.msu.edu/~hobartta/development.htm