3. integrated diabetes care: overview & discussion

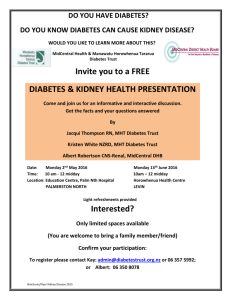

advertisement