Autonomy in Moral and Political Philosophy

advertisement

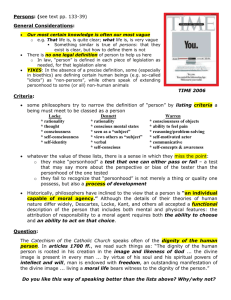

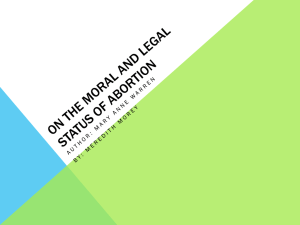

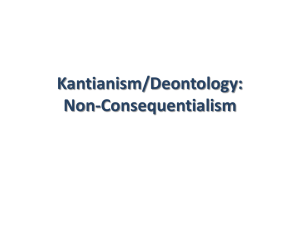

Autonomy in Moral and Political Philosophy 4th Year Jurisprudence O Sheils Individual autonomy is an idea that is generally understood to refer to the capacity to be one's own person, to live one's life according to reasons and motives that are taken as one's own and not the product of manipulative or distorting external forces. It is a central value in the Kantian tradition of moral philosophy but it is also given fundamental status in John Stuart Mill's version of utilitarian liberalism (Kant 1785/1983, Mill 1859/1975, ch. III). Examination of the concept of autonomy also figures centrally in debates over education policy, biomedical ethics, various legal freedoms and rights (such as freedom of speech and the right to privacy), as well as moral and political theory more broadly. In the realm of moral theory, seeing autonomy as a central value can be contrasted with alternative frameworks such an ethic of care, utilitarianism of some kinds, and an ethic of virtue. The Concept of Autonomy In the western tradition, the view that individual autonomy is a basic moral and political value is very much a modern development. Putting moral weight on an individual's ability to govern herself, independent of her place in a metaphysical order or her role in social structures and political institutions is very much the product of the Enlightenment humanism of which contemporary liberal political philosophy is an offshoot. Put most simply, to be autonomous is to be one's own person, to be directed by considerations, desires, conditions, and characteristics that are not simply imposed externally upon one, but are part of what can somehow be considered one's authentic self. Autonomy in this sense seems an irrefutable value, especially since its opposite — being guided by forces external to the self and which one cannot authentically embrace — seems to mark the height of oppression. But specifying more precisely the conditions of autonomy inevitably sparks controversy and invites skepticism about the claim that autonomy is an unqualified value for all individuals. Autonomy plays various roles in theoretical accounts of persons, conceptions of moral obligation and responsibility, the justification of social policies and in numerous aspects of political theory. Rights 4th Year Jurisprudence O Sheils A right is the power or privilege to which one is justly entitled or a thing to which one has a just claim. Many different types of rights have been described. Many of these terms describe overlapping concepts, and are often used interchangeably. Human rights refers to the concept of human beings as having universal rights, or status, regardless of legal jurisdiction, and likewise other localizing factors, such as ethnicity and nationality. Inalienable rights (or unalienable rights) refers to a set of absolute rights that are endowed by God, not awarded by any human power and not capable of being repudiated or transfered to another power. The phrase is most famously used in the United States Declaration of Independence, where "unalienable rights" are said to include "Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness." Civil rights are the protections and privileges of personal liberty given to all citizens by law. Contractual rights are those based on laws agreed upon between persons for whom those laws are valid. The concept of a right is extremely complex, given the wide variety of contexts in which the term 'right' may be properly used. The distinction of most philosophical and ethical interest is that between legal and moral rights. It is customary to differentiate these by distinguishing between, on the one hand, rights as acknowledged and accorded, and therefore protected by law and, on the other, rights as morally to be accorded, whether or not they are in fact acknowledged. It is not necessarily the case that legal recognition is always a desirable form of the acknowledgement of a right - we do not really want all of our rights to be legally sanctioned e.g. the mutual rights of spouses to be told the truth about each others' feelings. However, those rights which are properly to be enshrined in law are among the most important and it is they that have historically attracted most attention. Hence the distinction may be narrowed to one between rights as legally accorded and rights as properly to be legally accorded. There is an important distinction to be made between positive rights, which oblige others in some way, and negative rights, which free oneself from obligation or coercion. In most views of law, it is not generally considered necessary that a right should be understood by a holder of that right, thus rights may be agreed on behalf of another, such as children's rights or the rights of people declared mentally incompetent to understand their rights. However, rights must be understood by somebody in order to have legal existence, so the understanding of rights is a social prerequisite for the existence of rights. Therefore, educational opportunities within society have a close bearing upon the people's ability to erect adequate rights structures. Legal rights In modern English and European systems of jurisprudence and law, a right is the legal or moral entitlement to do or refrain from doing something or to obtain or refrain from obtaining an action, thing or recognition in civil society. Compare with duty, referring to behaviour that is expected or required of the citizen, and with privilege, referring to something that can be conferred and revoked. The specific enumeration of rights accorded to citizens has historically differed greatly from one century to the next, and from one regime to the next, but nowadays is normally addressed by the constitutions of the respective nations. Generally speaking (within the English and European systems) a right corresponds with a complementary obligation that others have on the same object or realm; for instance if someone has a right on a thing, simultaneously another party or parties have an obligation to do something (or to abstain from doing something) in order to respect that right or to give concrete execution to that right. The right can therefore be a faculty of doing something, of omitting or refusing to do something or of claiming something. Other interpretations consider the right as a sort of freedom of something or as the object of justice. In passing, we should also note that a rights campaign is usually as concerned to have certain legally accorded rights removed from the statute books as to have presently non-accorded rights recognised. Indeed these are often two sides of the same coin. Thus a campaign to get the law to accord freedom to slaves is also a campaign to get it to cease according some men the right to own others; a campaign to accord certain legal rights to workers is by the same token one to restrict the legal rights of employers. The point here is that, as well as the possibility that there are moral rights that should be legally recognised, but are not, it is also possible that one's legal rights include some one should not have. It is not, perhaps, always appreciated by rights campaigners that the opposition they arouse derives part of its strength from opponents' sense that their own rights are being threatened by the campaign. What, then, is distinctive about rights? 1. Rights entail duties. The concept of a right involves the correlativity of rights and duties, i.e. whenever someone has a right to something, someone else has the corresponding duty. For example, if I have a right to life then you (and everyone else) have the duty not to take my life; if I have a property right in my house, you (and everyone else) have the duty not to occupy or use my house without my permission. 2. A right-holder has control over the incidence of the duty. HLA Hart argues (in 'Are there any natural rights?') that a person who has a right is in a position either to demand that the corresponding duty be performed or to waive that duty viz. he has control over the incidence of the duty. However, Hart admits this account may not do for all cases – perhaps especially in regard to rights like the right to life where it has at least been traditional to claim that this right is not waivable. 3. Rights protect freedom. Hart asserts that there is a special connection between rights and the protection of freedom. He claims, for instance, that X has a right to what Y promised him if and only if Y has voluntarily promised to do so. Three things seem to follow from Hart's view: a) there is a general duty not to interfere with others' freedom. (This follows from the assumption that only something very formal like a promise will license a restriction on individual freedom) b) corresponding to this general duty of non-interference there is a right (which is waivable) not to have our freedom interfered with. c) an individual must waive this right if any interference with his/her freedom is to be justifiable. Positive and Negative Rights Is the notion of a right adequately fleshed out by the idea of non-interference? Some philosophers (e.g. HLA Hart) suggest that rights are fundamentally negative, i.e. they are about being allowed to do things and not prevented from acting in certain ways. Others, like Rawls and Dworkin, argue that social justice demands that some rights at least must be conceived positively, i.e. as rights to others' help and co-operation. The problem here is that if some rights impose positive duties of help, that will inevitably infringe on the individual's personal freedom to act as he/she wants (e.g. by controlling his/her own income and expenditure). It is sometimes argued, therefore, that positive rights amount to a violation of negative rights. Personhood 4th Year Jurisprudence O Sheils Are all persons human? Firstly, there is the simple view that the common usage is the correct one: that person does indeed mean human. However, this runs into the problem that the term person has a somewhat loaded meaning - we commonly believe that all and only persons have certain rights, for example, the right to life. Some would go so far as to say that all and only persons are sacred. However, we can imagine the hypothetical alien from another planet, who, despite not being human, nevertheless has every trait that we see as being essential for this protected status that elevates it above mere objects. Thus, many claim that the simple view implies a sort of arrogant speciesism (e.g. Peter Singer). There are also religious views that attribute personhood to supernatural beings (such as gods, angels, demons, elves, etc.) In fact, the present sense of the word person has developed in large part through reflection on the Trinitarian doctrine that God is one substance and three persons. Are all humans persons? Another problem with the simple view is that there are disputes over whether certain humans are persons. For example, in the abortion controversy, although the foetus is clearly of the human species, it is a matter of debate whether it is a person. Or in the case of a victim of severe brain damage who has no mental activity, some may claim that he or she is no longer a person, or that the person has ceased to exist, leaving only an "empty shell." A person, by some accounts, is one who, through his or her choices and decisions, has built a personal identity, which is active in further choices. A fetus has not yet had that opportunity (although the same could be said about a newborn child), and a severely brain-damaged person may no longer have the ability to act through further choices. Criteria for personhood The above points seem to indicate that there may be persons that are not human, and there may be humans that are not persons. For these reasons, many philosophers have tried to give a more precise definition, focusing on some trait or traits that all persons, real and hypothetical, must possess. The most obvious such trait that persons typically possess is a conscious mind, typically (but not necessarily) with plans, goals, desires, hopes, fears, and so on. Yet the claim that such a mind is necessary for personhood is also problematic, as most would consider human babies as persons, yet their minds do not seem sufficiently advanced to satisfy this condition. A few philosophers have simply accepted that babies are not persons. However, most have not. Instead, some have suggested that the potential for such a mind is the correct trait. Yet another view is that personhood is not all-or-nothing: there can be degrees of personhood, based on how close to a fully working mind the object in question has. Thus, a typical adult is entirely a person, while a human permanently in a coma is not a person at all. This view also seems to have some unpleasant consequences, for example, that a young child or someone with a moderate mental handicap might be, say, only half a person (and perhaps therefore have only half the rights, or be regarded as half as important). Jean Vanier, who has spent most of his life working and living with people with learning disabilities, has suggested that the capacity to be loved is what makes a true person. It is probably true to say that other views also exist, and that the debate is not close to being resolved. Moral rights and responsibility Closely related to the debate on the definition of personhood is the relationship between persons, moral rights, and moral responsibility. Many philosophers would agree that all and only persons are expected to be morally responsible, and that persons deserve maximal moral rights. There is less consensus on whether only persons deserve moral rights and whether persons deserve greater moral rights than non-persons. The rights of non-person animals is an example of contention on this issue (see animal rights).