What is Eurocentrism

advertisement

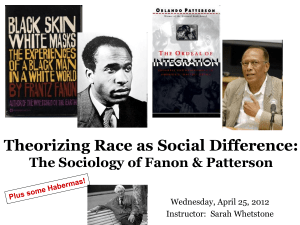

FROM EUROCENTRISM TO HIBRIDITY OR FROM SINGULARITY TO PLURALITY Titus Pop Partium Christian University, Oradea, Romania Introduction Since colonial times Europeans have perceived most of the world as open to conquest, control and domination. The population of the Third World has been perceived as weak or vicious, and as in need of being “civilized”. Whereas in classical European thinking, history and the past are the reference point for epistemology, in modern societies there appeared voices that have proposed a radical rethinking—an appropriation of the European thinking by a different discourse. In my paper I will refer to the thorny road from Eurocentrism to multiculturalism and hybridity. Beginning with a contrastive approach of Frantz Fanon’s and Mahatma Ghandhi’s visions of liberation, I will then point out the relevance of some scholars’ standpoints such as Said, Bhabha, or Bakhtin who have viewed cross-culturality as the possible ending point of an apparent endless human history of conquest and occupations. They recognize that the myth of purity or essence must be challenged and replaced by hybridity which, in turn, replaces a temporal linearity with a spatial plurality. Eurocentrism or Singularity Eurocentrism is the practice, conscious or otherwise, of placing emphasis on European (and, generally, Western) concerns, culture and values at the expense of those of other cultures. Eurocentrism often involved claiming cultures that were not white or European as being such, or denying their existence at all. Here are some examples of Eurocentric views. First of all, the regional names around the world are named in honour of European travelers and are in orientation of a Eurocentric worldview. Middle East describes an area slightly east of Europe. The Orient or Far East is east of Europe, whereas the West is Western Europe and the Americas (although in modern geopolitical parlance the West also includes South Africa, Australia and can include Japan). The effects of Eurocentricism create a self-sustaining belief that Europe and Europeans are central and most important to all meaningful aspects of the world’s social values, and cultural heritage. Secondly, World History taught in European and American schools frequently teaches only the history of Europe and the United States in detail, with only a brief mention of events in Asia, Africa and Latin America. The Americas, Africa and Australasia are usually not mentioned in the timeline until they are colonized by Europeans, with no reference to the pre-conquest culture, civilization or technology. Thirdly, the history of science and technology is often taught as having begun with the Greeks, then moving on with the Romans, then stopping during the Dark Ages, before continuing with the Renaissance and the Industrial Revolution. Less mention is 1 made in European or American schools of the various achievements of Indian, Chinese, Ancient Egyptian, Moorish or other Muslim thinkers. Another example of Eurocentrism are the Western accounts of the history of mathematics which are often considered Eurocentric in that they do not acknowledge major contributions of mathematics from other regions of the world such as Indian mathematics, Chinese mathematics and Islamic mathematics. At the same time, university courses on the history of human thought that cover Aristotle, Kant and Marx but neglect Confucius, Buddha, the Upanishads, for example, might also be regarded as Eurocentric. Distortion of Reality Assumptions of European superiority arose during the period of European imperialism, which started slowly in the 16th century, accelerated in the 17th and 18th centuries and reached its zenith in the 19th century. After discussing some aspects of colonial structural constructs which had painful effects on the colonized peoples as seen by some post-colonial critics, I will touch upon the need of recovery of the colonized peoples. Such aspects of painful experiences are largely treated from different perspectives by a range of intellectuals such as Fanon, Spivak, and Gandhi, to name the most revolutionary ones, and Edward Said, and Bhabha, Rushdie or C. Achebe, who proposed a milder approach. But they all speak about a distortion of reality made by the colonizing culture, a culture that used its military dominance accompanied by cultural knowledge to exert its hegemony over the colonized peoples. Reality has been distorted to the benefit of the colonizing powers ever since imperialism existed. The native has been painted in a negative way by the settlers from the very outset of the colonial process. In The Wretched of the Earth, Franz Fanon quotes Monsieur Meyer, the representative of the French imperial power in Algeria, and describes how the native is gradually portrayed as a kind of quintessence of evil. Not only is he presented as invaluable, but he is seen as the negation of values: he is, let us dare to admit, the enemy of values, and in this sense he is the absolute evil…the corrosive element, destroying all that comes over him: he is the deforming element…the depository of maleficent powers, the unconscious and irretrievable instrument of blind forces. (Fanon, Wretched 40) These words were uttered by the French official in front of the French National Assembly before the start of the Algerian war and what they denote is an undoubtedly superior if not a violent attitude towards the natives. The native has thus been condemned to immobility and to inferiority from the very beginning. The native, or the colonized, is taught to stay in his place and not to go beyond certain limits. Fanon also explains why these confinements to which the native has been subjected turn into violence. This is why the native’s dreams are of action and oppression. What he cannot do during the day he dreams of doing at night. These dreams start then to burst out in various forms. First of all, the native reacts violently against his fellow beings: “The native is an oppressed person whose permanent dream is to become the persecutor. The impulse to take the settler’s place implies a tonicity of muscles the whole time” (52). This muscular tension leads to bloodthirsty explosions of different 2 forms—tribal wars, religious feuds, terrorist attacks and fights between individuals. Fanon continues saying that by this collective self-destruction the native’s muscular tension eases. In my view, Fanon’s theory is applicable to contemporary neocolonialism practiced by the West, namely by the United States. There is nothing less obvious today than what is happening in the occupied Irak where the Shia fights the Sunni, suicide bombs explode killing both occupying force soldiers and fellow citizens or in the West Bank and Gaza Strip where Palestinian grenade-strapped youths blow themselves up in despair or in Groznai where Chechen fighters fight to the last drop of life. According to Fanon, this pattern of conduct is that of a death reflex when confronted with danger, a suicidal behaviour. To the Christian settler, who scorns suicidal acts, this is a proof that the natives are not reasonable human beings But there are other reasons why the colonized peoples moved to violence against the settlers. At first, there are nationalist political parties which during the colonial period hold dissertations on themes like the human rights and self-determination, human dignity and the like. These parties produce elites who give hope, though tacitly, to the wretched. An eloquent example of such a case is Mahatma Gandhi. Gandhi was a milder ideologist than Fanon as far as the native’s fight for freedom is concerned. Still, it is worth discussing the two persons’ views contrastively. Whereas Gandhi has a religio-political discourse, Fanon’s vocabulary resembles Sartre’s existential humanism. If Gandhi talks about a theology of non-violence after his encounter with British imperialism, Fanon’s experience of French colonialism produces a theory calling for collective violence. However, there are many similarities between the two thinkers at least from the position they are speaking; they both study in the colonizing country; they both prepare their anti-colonialist theories in a third country— Gandhi in South Africa and Fanon in Algeria; they both deny the nationalist policy of the elitist parties in their countries and militate for a decentralized polity closer to the needs of the huge uninformed mass of the Indian and Algerian peasantry. In addition to this, Gandhi and Fanon think alike in their proposal of a radical style of complete resistance to the totalising political and cultural offensive of the colonial civilizing mission. They insist on the psychological resistance to colonialism: ’Total liberation is that which concerns all sectors of the personality” (Fanon, Black Skin 250). By previously stating that “the dominant psychological feature of the colonized is to withdraw before any invitation of the conquerors” (250), Fanon’s vision is that the only way of resisting is by refusing the privilege of recognition to the colonial master. In turn, Gandhi laments the Indian desire for the superficiality of modern civilization. Here is what he says: “We brought the English, and we keep them. Why do you forget that our adoption of their civilization makes their presence in India at all possible? Your hatred against them ought to be transferred to their civilization” (Gandhi 66). Another similitude in Fanon and Gandhi is their common vision on national liberation as an imagination pretext for cultural self-determination from Europe and as an attempt to exceed the claims of Western civilization. In his second book, Black Skins, White Masks, Fanon proposes the following: Let us try to create the whole man, whom Europe has been incapable of bringing to triumphant birth’ By this defiant attitude, he calls for alterity or cultural 3 difference. In this book , he invokes both Hegel and Sartre to render the condition of the colonized slave as a symptom of ‘imitativeness. (252) Gandhi has a similar view preferring the English rule without the English: “you want the tiger’s nature but not the tiger” (Gandhi 30). To put it differently, the only progress was to render the English, the ’tiger’, as undesirable. It is with these powerful attempts to demistify the claims of Western civilization that Fanon and Gandhi rewrite the narrative of Western or Eurocentric modernity. Industrialization is seen as the story of economic exploitation, technology is combined with warfare and the history of medicine is related by Fanon to the techniques of torture. While Gandhi’s Hind Swaraj narrates the structural violence of Western modernity, Fanon denounces the European myths of progress and humanism. When discussing civilization, Fanon laments: “When I search for man I see only a succession of negations of man, and an avalanche of murders” (Black Skins 252). Similarly, in an interview given to a British journalist, Gandhi, when asked what he thought about the English civilization, he answered: “I think it would be a good idea” (quoted in Rushdie’s Imaginary Homelands 138). Therefore, we may differentiate two types of colonial dominance—a violent colonialism that dealt effectively with the physical conquest of territories and which took place chronologically; and a more insidious one, a cultural colonialism pioneered by rationalists, modernists and liberals who occupied the minds, selves and cultures of the colonized. Thus, there emerged an elaboration of some strategies of profusion that helped persuade the colonized the idea that imperialism was really a messianic harbinger of civilization to the uncivilized world. On such a matter Edward Said developed a coherent point of view. In his now famous Orientalism and in his later book, Culture and Imperialism, not only does he consider the colonized as being purportedly orientalized, that is, portrayed by the Western scholars in such a way as to acknowledge their inferiority, but he also demonstrates how the others have been in desperate need of being represented. Beginning his book with Disraeli’s words who said in Tancred that “the East is a career” (Said, Orientalism 1), Said details the subtle elaboration of French and British colonial systems to which culture in general and literature in particular contributed to a great extent. He directs attention to the discursive and textual production of colonial meanings and to the creation of a structure of attitude and reference and of a consolidated vision of colonial hegemony. By analyzing a range of colonial texts and other cultural products, Said created the mostly debated aspect of postcolonial theory. What he does is the exploration of the historical imbalanced relationship between the world of Islam, the Middle East and the Orient on the one hand, and that of European and American imperialism on the other. Said postulates a unique understanding of colonialism and imperialism as the cultural attitude which accompanies the habit of ruling distant territories. This vision is reiterated in Culture and Imperialism where he writes: Neither imperialism nor colonialism is a simple act of accummulation and acquisition. Both are supported and perhaps even impelled by impressive ideological formations that include notions that certain territories and people require and beseech domination, as well as forms of domination … the 4 vocabulary of classic nineteenth century imperial culture is plentiful with such words and concepts as ‘inferior’ or ‘subject races’, ‘subordinate peoples’, ‘dependency’, ’expansion’ and ‘authority. (8) Following Mikhail Bakhtin's assertion that hell is the “absolute lack of being heard” (Bakhtin, Discourse 126), it can be argued that non-European and non-white peoples were living in such a kind of hell during most of the period of colonization. The term ‘Orientalism’ itself is seen as a project of teaching, writing about and researching the Orient. Orientalism, as a discipline, has been an essential cognitive inducement to Europe’s imperial adventures in the hypothetical ‘East’. In his vision, Orientalism is nothing but a “Western style for dominating, restructuring and having authority over the Orient” (Orientalism 3). To put it differently, according to this theory, the West elaborated a consolidated discourse by which it managed to produce the Orient politically, ideologically, militarily and imaginatively. Therefore, we know the Orient as it has been presented to us by the Western colonial discourse. Orientalism, which always presented Christendom as superior and as a representation of European domination of the Orient, served to enhance hostility between Islam and Christianity. This Western attitude is related to the spread of Islam over a large part of the Western world at the beginning of the fourteenth century, a threat which represented a lasting trauma to the Europeans and provoked what Samuel Huntington called “a clash of civilizations” between the two unequal halves of the world. The latter’s theory was recently heavily attacked by Said in a lecture he gave at MIT in Boston called “The Myth of the Clash of Civilization” labeling Huntington’s theory as a continuation of the Cold War (Said, “Myth”). Therefore, the Orient is, in Said’s terms, an arbitrary construct of Western culture, invented as a sweepingly wholesale and basically negative, though fascinating, mirror image which serves to cast a positive light on the West or to give the Occident its identity. The West first constructs the East as its cultural Other and then it makes the other conform to the Western image. Every instance of European curiosity about the Other, from Flaubert to Marx, from Austen to Conrad, from Dickens to Verdi, was part of a great project to exploit and remake what westerners saw as a positive rich, but ultimately contemptible ‘Oriental’ sphere. This idea perfectly pervades Disraeli’s words put in the mouth of Lord Macaulay, “the East is a Career,” with which Said starts his discourse. The context of Lord Macaulay’s words is his considering India as both a barbarous source of potential riches and as a huge tract in need of civilization. Said goes on and says that these constructs of debasement and “otherness” that were used until the 19th century, were still in use at the end of the 20th century. Such an attitude results from a character from Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, Saladin Chamcha, who is an immigrant in London and who acknowledges the Western power of representation: “They have the power of description, and we succumb to the pictures they construct” (168). One of the main features of postcolonial literatures is the issue of the colonized people’s recovery of the relationship between self and place. In their study on postcolonial literatures entitled The Empire Writes Back, Ashcroft, Griffith and Tiffin point out the dialectic of place and displacement as being the defining model of postcolonial literatures. The sense of self may have been eroded primarily by the cultural oppression the native personality has undergone. A new generation of educated natives 5 such as Hanif Kureishi, Thimothy Mo, Chinua Achebe, Hgungi wa Thiongo, Arundhati Roy or Salman Rushdie was finally able to use the tools they acquired through their encounter with the West to combat those representations, opening up new galaxies of ideas and creating new literary spheres. In those spheres new ways of reading and writing paved the way for new perspectives, broke ground for new avenues of thought, decoding the deep-seated images of colonial representation and re-coding new images of the self in order to escape the chain that was all too signifying. Thus, from that moment on, there emerged what Chinua Achebe called “the process of ‘re-storying’ peoples who had been knocked silent by the trauma of all kinds of dispossession” (79). At the same time, Said declares his desire to transcend what he calls “a rhetoric of blame” and to adopt “what might be called a comparative literature of imperialism” (Said, Culture and Imperialism 18). Thus, Said’s aim in re-reading those canonical works of empire is far from “condemning or ignoring their participation in what was an unquestioned reality in their society" (xiv). It is rather an attempt to read and understand, even to appreciate, them without being implicated in their ideological messages and hegemonic influences. Consequently, Said aims not simply to prove the falsity of the image of the Oriental in Western discourse, but rather to point out the fact of its being a discourse. This fact, in itself, explains how these reductive images have been transformed, through language, into truths in Nietzsche’s sense of the word. Here Said quotes Nietzsche’s opinion that truths are but “a mobile army of metaphors, metonyms, and anthropomorphisms ... which after long use seem firm, canonical, and obligatory to a people: truths are illusions about which one has forgotten that this is what they are” (Said, Orientalism 203). Hence, the process of unveiling their systematic nature as part of a whole discourse becomes, for Said, the first step in deconstructing them. Hybridity and Plurality Following Said’s enterprise, other writers, such as Homi Bhabha, Salman Rushdie, Wilson Harris or Edward Brothwaite, who proceed from a consideration of the nature of postcolonial societies and the types of hybridization these various cultures have produced, proposed a radical rethinking—an appropriation of the European thinking by a different discourse. Whereas in European thinking, history and the past are the reference point for epistemology, in postcolonial thought space annihilates time. History is rewritten and realigned from the standpoint of the victims of the destructive progress. Hybridity replaces a temporal linearity with a spatial plurality. Salman Rushdie makes this obvious when commenting on the message of his controversial novel, The Satanic Verses, in an essay called “In Good Faith” as follows: The Satanic Verses celebrates hybridity, impurity, intermingling, the transformation that comes of new and unexpected combinations of human beings, cultures, ideas, politics, movies, songs. It rejoices in mongrelization and fears the absolutism of the Pure. Melange, hotchpotch, a bit of this and a bit of that is how newness enters the world. It is the great possibility that mass migration gives the world, and I have tried to embrace it. The Satanic Verses is for change-by-fusion, change-by-conjoining. It is a love-song to our mongrel selves. (394) 6 Even though on the surface postcolonial texts may contain race divisions and cultural differences, they all contain germs of community which, as they grow in the mind of the reader, they detach from the apparently inescapable dialectic of history. Thus, postcolonial literatures have begun to deal with problems of transmuting time into space and of attempting to construct a future. It highlights the acceptance of difference on equal terms. Now both literary critics and historians are recognizing cross-culturality as the possible ending point of an apparent endless human history of conquest and occupations. They recognize that the myth of purity or essence, the Eurocentric viewpoint must be challenged. The recent approaches show that the power of postcolonial theory lies in its comparative methodology and the hybridized and syncretic view of the modern world which it implies. Of the various points in which postcolonial texts intersect, place has a paramount importance. In his dialogism thesis, Mikhail Bakhtin emphasizes a space of enunciation where negotiation of discursive doubleness gives birth to a new speech act: The hybrid is not only double-voiced and double-accented . . . but is also doublelanguaged; for in it there are not only (and not even so much) two individual consciounesses, two voices, two accents, as there are [doublings of] sociolinguistic consciousnesses, two epochs . . . that come together and consciously fight it out on the territory of the utterance. (Dialogic 360) Also, Homi Bhabha talks about a third space of communication, a hybrid space or a new position in which communication is possible. In a recent article Bhabha explains that such negotiation is neither assimilation nor collaboration as it makes possible the emergence of an “interstitial” agency that refuses the binary representation of social antagonism. Hybrid agencies find their voice in a dialectic that does not seek cultural supremacy or sovereignty. They deploy the partial culture from which they emerge to construct visions of community, and versions of historic memory, that give narrative form to the minority positions they occupy: “the outside of the inside; the part in the whole” (“Culture’s”). As an example, Bhabha mentions Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved in which cultural and communal knowledge comes as a kind of self-love that is also the love of the “other”. This knowledge is visible in those intriguing chapters where Sethe, Beloved, and Denver perform a ceremony of claiming and naming through intersecting interstitial subjectivities: “Beloved, she my daughter”; “Beloved is my sister”; “I am beloved and she is mine.” The women speak in tongues, form a fugal space “in-between each other” which is a communal space. They explore an “interpersonal” reality: a social reality that appears within the poetic image as if it were in parenthesis—esthetically distanced, held back, yet historically framed. It is difficult to convey the rhythm and the improvisation of those chapters, but it is impossible not to see in them the healing of history, a community reclaimed in the making of a name (“Culture’s”). This “new position” Bhabha proposes is closely related to the “homeless” existence of post-colonial persons. It certainly cannot be assumed to be an independent third space already there, a “no-man’s-land” between the nations. Instead, a way of cultural syncretization, i.e. a medium of negotiating cultural antagonisms, has to be created. Cultural difference has to be acknowledged: “Culture does imply difference, but the differences now are no longer, if you wish, taxonomical; they are interactive and 7 refractive” (Bhabha quoted in Rutherford 221). This position emphasizes, contrary to the too facile assumption of world literature and world culture as the stages of a multicultural cosmopolitanism already in existence, that the “intellectual trade” takes place mostly on the borders and in the border crossings between cultures where meanings and values are not codified but misunderstood, misrepresented, even falsely adopted (207). Bhabha explains how beyond fixed cultural (ethnic, gender- and class-related) identities, so-called “hybrid” identities are formed by discontinuous translation and negotiation. Thus, former tribal societies translate their traditional “identity”, their own national text, into Western forms of information technology, of consumption, fashion etc. New hybrid identities arise similarly in the course of the political and cultural reorientation of former colonial societies: “hybridity to me is the 'third space' which enables other positions to emerge” (211) Hybridity is the key term that marks a sphere in which the cultural other is confronted within the network of cultures and in which different traditions often clash. In this respect, in conclusion, it is worth mentioning here Jacques Derrida’s view on difference: We all require “culture,” but let us cultivate (colere) a culture of selfdifferentiation, of differing with itself, where “identity” is an effect of difference, rather than cultivating “colonies” (also from colere) of the same in a culture of identity which gathers itself to itself in common defense against the other. (Caputo 115) Works cited Achebe, Chinua. Home and Exile. Oxford: OUP, 2000. Ashcroft, Bill, Gareth Griffiths and Helen Tiffin. The Empire Writes Back. London: Routledge, 2002. Bhabha Homi K. “Culture’s in between.” Artforum International, Vol. 32, September 1993, accessed on Jan 28th 2007 at www.questia.com Bakhtin, Mikhail. Speech Genres and Other Late Essays. Ed. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. Trans. Vern W. McGee. Austin: U of Texas P, 1986. ---. “Discourse in the Novel.” The Dialogic Imagination. Ed. Michael Holquist. Trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist, Austin: U of Texas P, 1981. Caputo, John D. and Jacques Derrida. Deconstruction in a Nutshell: A Conversation with Jacques Derrida. New York:Fordham University Press, 1997. Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White masks. New York: Grove, 1967. ---. The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove, 1961. Gandhi, Mahatma. Hind Swaraj and Home Rule. Naveed House Publishing Accessed on Jan.25th 2007 http://www.mkgandhi.org/swarajya/coverpage.htm Morrison, Toni. Beloved. New York: Plume/NAL, 1987. Rushdie, Salman. The Satanic Verses. London: Vintage, 1989. Rutherford, J. “The Third Space: Interview with Homi Bhabha”. Identity. Community, Culture, Difference. London: Laurence and Wishart, 1990. 220-226. 8 ---. The Midnight’s Children. London: Vintage, 1995. ---. Imaginary Homelands. London: Granta Books, 1991. Said, Edward. Culture and Imperialism. London: Vintage, 1994. ---. Orientalism. London: Penguin, 1978. ---. “The Myth of The Clash of Civilization”. Lecture at MIT, Boston, accessed on January 30th at www.youtube.com 9