The value relevance of foreign currency translation adjustments in

advertisement

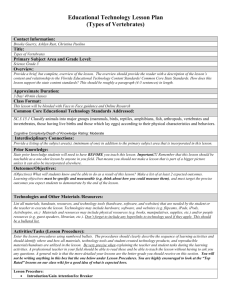

The value relevance of foreign currency translation adjustments in the Italian Stock Exchange 1. Introduction In September 2007, the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) issued Statement of International Accounting Standard No. 1 (IAS 1), ‘‘Presentation of Financial Statement’’. This standard, effective for fiscal years beginning after December 31 2008, requires that comprehensive income (CI) and its components, net income (NI) and other comprehensive income (OCI) be reported in the financial statements in the period in which they are recognized, consistently with what is already forseen in the U.S. context (Bragg, 1997; Carlson et al., 1999; Fitzsimmons and Thomson, 1996; Luecke and Meeting, 1998; Stevens, 1997). Al listed firms are required to clearly disclose, in an ad hoc document, unrealized gains and losses on revaluation of property, plant, and equipment, actuarial gains and losses on defined benefit post-employment plans, foreign exchange differences on monetary items and on net investments in foreign entities, revaluation of intangible assets, gains and losses on available for sale financial instruments, effective portion of gains and losses on derivatives used as hedging instruments in a cash flow hedge. Of OCI, foreign currency translation adjustments (FCTA) are the largest element for most firms (Dee, 1999) and on this element our research will focus. The main research question in this study is whether reported FCTA are considered to be value relevant by investors. An accounting value is value relevant if it is considered in the investor’s business valuation process, therefore the main aim of the paper is to investigate whether the reported FCTA numbers provide investors with an incremental value in terms of information content with respect to NI. Previous empirical studies in other countries document mixed evidence on the usefulness to investors of OCI information, and the majority of the published archival research (Cheng et al.1993; Dhaliwal et al.1999; Dehning and Ratliff, 2004) has not found consistent support for the value relevance of OCI. It is important to point out that the majority of these studies use data from the period before implementation of CI reporting according to accounting standards, and this could have led to significant measurement errors and to a lack of information transparency. Differently from previous prevailing research, we examine the value relevance of FCTA items using actual as reported OCI numbers. As regards the specific literature review on FCTA value relevance, empirical evidence presented in both the finance and accounting literatures has documented either a weak or nonexistent link between foreign exchange rate movements and firm valuation (Pinto, 2005) probably due to a misspecification of econometric model used. On the one hand our study contributes to the ongoing debate on OCI value relevance, in detail FCTA value relevance, and on the other it is, to the best of our knowledge, the first empirical research to investigate the value relevance of FCTA in the Italian context using as reported OCI numbers, panel techniques and allowing FCTA to vary conditional to the amount of assets. The analysis has been carried out for the two-year period 2008-2009 for all listed companies on the Italian Stock Exchange, excluding companies belonging to the financial sector. This sample of firms, therefore, provides a unique setting in which to inform Italian policy makers of the value relevance of the additional information included in the new accounting standards. We find that the as reported FCTA numbers are positively priced in the post-IAS 1 revised 2007 period. These results also have implications for the current accounting practice of FCTA. The main issue is that the results of this study contradict the notion that foreign currency translation adjustments are mere ‘‘bookkeeping’’ entries and thus do not affect valuation. Our contribution to the literature is twofold. First, the choice of using the two year period 20082009 allowed us to employ in the analysis post-IAS 1 revised 2007 data, more appropriate for assessing whether investors better understand the value implications of components of other comprehensive income. Second, the findings of this study support the approach adopted by standard setters to introduce fair value changes in the statement of other comprehensive income, since the improved transparency of the information on OCI turned the negative findings of the OCI value relevance into a positive and significant incremental value relevance of OCI information. This paper is structured as follows. In section two, the main accounting novelties as regards CI disclosure according to the IAS 1 revised 2007 are illustrated. Section three then develops a review of the literature on the main previous studies on FCTA value relevance. The fourth section illustrates the research hypotheses, together with the methodology used. Section 5 describes the sample selection process, while section 6 reports the main results of the OCI incremental value relevance regressions. The paper concludes with discussion of the main results and perspectives for future research. 2. The mandatory disclosure of other comprensive components by IAS 1 2007 revised The main objective of the IAS 1 revised 2007 “Presentation of Financial Statements” is to align European normative accounting standards to the principles of US SFAS 130. The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) issued Statement of Financial Accounting Standards no. 130 “Reporting Comprehensive Income”, in June 1997, mandatory for fiscal years beginning after 15 December 1997. This standard intervened to settle the long-standing debate in the accounting profession between the ‘all-inclusive’ (or ‘comprehensive income’) and ‘current operating performance’ concepts by embracing the comprehensive income approach (Dhaliwal et al., 1999; Biddle and Choi, 2006; Chambers et al., 2007). This approach became more and more relevant due to the increased use of fair value in accounting standards, which generated, among other things, changes in the valuation of items comprehended in the CI aggregate (Whittington, 2005). Under the all-inclusive concept, unlike the current operating approach, income includes all revenues, expenses, gains, and losses, whether extraordinary or otherwise. The idea behind this is that income on a comprehensive basis is a better measure of firm performance than other narrower summary income measures because it includes all changes in the net assets of a firm during a period coming from non-owner sources. As regards the disclosure rules, SFAS 130 mandates companies to report CI and its component adjustments, collectively referred to as OCI, in firms’ financial statements. In Europe prior to 2007, there were no accounting standards that regulated the disclosure of CI and its components. In issuing IAS1 revised 2007, IASB adopted the CI approach, with the aim of improving the usefulness of corporate performance information for investors and the transparency of financial statements. As a result, listed Italian companies have been obliged, for the fiscal years beginning after 31 December 2008, to disclose the CI in an ad hoc statement, that reports the NI figure, the OCI items and the CI figure. Conceptually, the disclosure of an income measure beyond the NI figure allows, on the one hand, for measurement of the firm’s future performance because it also takes into consideration the unrealized earnings, susceptible to the production of cash flow in the future, and on the other hand it uses a fair value evaluation rather than the historical cost evaluation. IAS 1 revised 2007 defines the OCI components. OCI consists of revenues, expenses, gains and losses that are excluded from net income and are consistent with one of five classifications: (1) changes in revaluation surplus (IAS 16 and IAS 38); (2) actuarial gains and losses on defined benefit plans (IAS 19); (3) gains and losses arising from translating the financial statements of a foreign operation (IAS 21); (4) gains and losses on available-for-sale financial assets (hereafter IAS 39a); (5) the effective portion of gains and losses on hedging instruments in a cash flow hedge (hereafter IAS 39b). In particular our study focuses on the exchange rate changes, as measured by FCTA. Gains or losses resulting from the process of expressing amounts denominated or measured in one currency in terms of another currency by use of the exchange rate between the two currencies. This process is generally required to consolidate the financial statements of foreign affiliates into the total company financial statements and to recognize the conversion of foreign currency or the settlement of a receivable or payable denominated in foreign currency at a rate different from that at which the item is recorded. Translation adjustments are not included in determining net income, but are disclosed as separate components of OCI. From an accounting point of view, is IAS 21 that deal with issues such as which exchange rate(s) to use and how to report the effects of changes in exchange rates in the financial statements. The objective of IAS 21 is to prescribe how to include foreign currency transactions and foreign operations in the financial statements of an entity and how to translate financial statements into a presentation currency. 3. Literature review on the value relevance of the foreign currency translation adjustment The issue of exchange rate exposure has been examined by accounting researchers for more than a quarter century (Aliber and Stickney, 1975; Aggarwal, 1978; Beaver and Wolfson, 1982; Houston, 1989; Boatler, 1992; Callaghan and Bazaz, 1992; Bartov, 1997; Louis, 2003). The extant empirical evidence (Callaghan and Bazaz, 1992; Soo and Soo, 1994; Pourciau and Chaefer, 1995; Bartov, 1997) provided mixed results. Paradoxically, empirical evidence presented in both the finance and accounting literatures has documented either a weak or nonexistent link between foreign exchange rate movements and firm valuation. Jorion (1990) investigating US multinationals firms, finds a low rate of stock price reaction to currency movements. Soo and Soo (1994) report earnings response coefficients of FCTA significantly smaller relative to those estimated on net income. As regards the researches on FCTA as an item of OCI, empirical results presented in both Dee (1999) and Dhaliwal et al. (1999) suggest that FCTA are not value relevant. Chambers et al. (2007) investigated OCI value relevance by using as-if OCI for the pre SFAS 130 years and as-reported OCI for the post SFAS 130 years. The results show that as if OCI numbers are never value relevant (both in the pre- or in the post- SFAS period), but that the as reported OCI numbers are value relevant in the post SFAS period. They also document that two components of OCI, foreign currency translation adjustment and unrealized gains/losses on available-for-sale securities are priced by investors. ‘O Hanlon and Pope (1999), in spite of their extension of the temporal interval investigated, failed to prove, for UK firms, that OCI items are value-relevant. Cahan et al. (2000) succeeded in proving the value relevance of CI for New Zealand companies, due to changes in currency translation reserve, but failed to prove that OCI components have incremental value relevance above their aggregate sum. Brimble and Hodgson (2004) failed to find evidence of the value relevance of OCI items in Australia, similarly to Wang et al. in The Netherlands (2006). Kubota et al. (2007) failed to prove that CI possesses superior information content with respect to NI for Japanese firms, but succeeded in proving that the OCI items they chose, “changes in cumulative foreign currency translation adjustments” and “changes in the balance of unrealized gains and losses on securities available-for-sale” possess significant incremental information content. Also Goncharov and Hodgson (2008), using a massive dataset for 16 European countries, found that OCI provides incremental information to investors, due to unrealized available-for-sale security components. Lin (2006), for UK firms, succeeded in proving that OCI items disclosed as required by FSR3 (change in foreign currency translation gains and losses, change in assets revaluation and changes in other recognised gains and losses) are value relevant beyond NI, as are movements in shareholders’ funds, disclosed as well in compliance to UK accounting standard (FRS3). Kanagaretnam et al. (2009) found that CI is more value relevant than NI for Canadian firms, showing also that available-for-sale (SEC) and cash flow hedge (HEDGE) components are significantly associated with price and market returns. Several could be the probable reasons associated to the mixed evidence of the empirical literature on FCTA value relevance. Among these, we can cite that previous studies do not employ panel data techniques, they do not employ as-reported numbers and they, with the exception of Pinto (2005), do not use an interacted model to allow the FCTA to vary conditioned on firm’s assets. Pinto (2005), employing an equity valuation model allowing for the value relevance of FCTA to vary conditioned on location of foreign direct investment, capital intensity and exchange rate shocks, provide evidence that FCTA are significantly incrementally value relevant when their parameter estimates are allowed to vary cross-sectionally according to such relevant factors. For all these treason, we decided to test the FCTA value relevance by employing an Ohlson-like valuation method, trying to establish a correlation between accounting variables and equity prices using panel techniques, which allow to take into consideration individual heterogeneity. Moreover, we decided to use as reported FCTA numbers and to include in the valuation equation an interaction term to allow the FCTA to vary conditioned on firm’s assets. 4. Research Hypotheses and methodology The main objective of this study is to investigate whether the as reported FCTA is incrementally value relevant for Italian investors. Formally, we express the following research hypothesis: H1: the as reported FCTA provide additional information for investors. In investigating the value relevance of FCTA numbers, we used a panel estimates method, in order to control for unobserved heterogeneity of companies. Previous research based on panel models and addressing the market impact of accounting information is scarce, especially on European markets (Naceur and Goaied, 2004). Panel models, by combining at the same time cross-section and time series approaches, allow for the consideration of the dynamic aspect of a relationship, since companies are monitored within time, to control for time-invariant individual heterogeneity, thus reducing the omitted variable bias problems and improving the efficiency of the estimates, by extending the number of observations (Baltagi, 1995; Arellano, 2003). Karathanasis and Spilioti (2005), in testing the Ohlson model using a combination of time-series and cross-section data, proved that only panel methods are able to overcome statistical problems such as auto-correlation, collinearity among independent variables and heterogeneous dispersion. For all these reasons we have decided to employ panel models to investigate the value relevance of FCTA numbers. We use an incremental comparison test instead of a relative value relevance test. The incremental test has to be applied when a measure is viewed as given and an assessment is desired regarding the incremental contribution of another measure (van Cauwenberge and de Beelde 2010). We think that assessing the value relevance of FTCA as component of OCI numbers fits with this definition, since we are interested in investigating whether the supplemental disclosure of FCTA has a relevant information content for investors beyond NI. In the paper, we adopt the measurement perspective, unlike the majority of studies included in the CI literature, mainly because it is grounded on a rigorous valuation model, validated by academic literature. Kothari and Zimmermann (1995), comparing price and return models, recognized that earnings coefficients are less biased in the price models than in return models, only suggesting to researchers using price models to exercise more care in drawing statistical inferences, by using standard errors estimates robust to heteroscedasticity problems. Unlike the majority of literature ob FCTA value relevance, therefore, we use a price model. Our choice is justified by the circumstance that simple return-earning models, used under the informational approach, do not explicitly incorporate book value of equity as an explicative variable, and are thus not well specified (Collins et al., 1999). Following them, as we did. Within the measurement comprehensive income value relevance literature we refer to the Ohlson model –OM (1995), by applying a Ohlson (1995) like model. The OM (1995) is considered the main reference point in market based accounting research (Lo and Lys, 2000; Giner and Iniguez, 2006) and its success amongst accounting scholars is due to its development of a rigorous but simple theory for firm evaluation in terms of accounting values1. Starting from the OM (1995) valuation equation, the model estimated in the research is the following: Pi ,t 6 0 1 BVPS i ,t 2 EPSi ,t 3 D1 4 D1* EPSi ,t 5 FCTAi ,t 6 APSH 7 FCTA * APSH 8 Dyear i ,t (1) Due to recognition in the literature (“The Ohlson (1995) and Feltham and Ohlson (1995) studies stand among the most important developments in capital markets research in recent years. The studies provide a foundation for redefining the appropriate objective of [valuation] research.” Bernard (1995, 733); “The Ohlson (1995) and Feltham and Ohlson (1995) papers are landmark works in financial accounting.” (Lundholm, 1995, 749)) and to the impact of the model on contemporary accounting literature (Dechow et al., 1999), the Ohlson model (1995) is not just influential, but is becoming a “classic” (Lo and Lys, 2000). Several subsequent versions of the model have been issued, but in this paper we use the original version of the Ohlson model (1995), since a recent empirical study (Giñer and Iníguez, 2006) has shown that models based on the original version are able to explain share prices with greater accuracy and fewer distortions of the real data than more complex models, such as, for example, that of Feltham-Ohlson (1995). 1 Following Ohlson’s suggestions (Ohlson, 2000), all data are reported on a per-share basis, dividing the total values for the number of shares outstanding at the company's year-end or directly using the per-share values for data downloaded by the database Datastream. This is a technique, known as scaling, that allows reduction of measurement error and/or omitted variable bias, assuming that the number of shares is related to them (Barth and Clinch, 2005; Courteau, 2008). Pit+6 is the stock price 6 months after the end of the fiscal year. Consistently with other studies (Agostino et al., 2010), we chose to take the price into the model six months after, since annual accounts are not publicly available for investors at the end of the year; the investors have to wait for the approval (due, according to first call, for the end of April), and then for the publication of the annual accounts (one month later). All other variables are taken at the end of the year. BVPSit is book value per-share cum dividends, EPSit is earnings per share, D1 is a dummy coded 1 when EPS is negative and 0 otherwise. D1*EPS is the interaction term. In this way, we controlled for the well known differential valuation of negative earnings (Hayn, 1995; Sin and Watts, 2000; Giñer and Iníguez, 2006; Kodadadi and Reza Emami, 2010). In fact, the use of the dummy variable and the multiplicative interaction term (Braumoeller, 2004) controls for the timelier recognition of losses in comparison to gains which is often referred to as conditional conservatism (Basu, 1997). We also include as control variable the size of the companies, measured through the assets per share (APSH). Controlling for company size has the aim of avoiding that results be primarily driven by larger firms, biased by scale differences. Moreover, in the model we take into consideration that assets controlled by the firm may provide a shield against exchange rate risk (Collins and Salatka, 1993), by introducing, consistently with Pinto (2005), an interaction term (APSH*FCTA). This parameter is expected to have a negative coefficient. Finally, temporal dummies (Dyear) are included in order to take into consideration unexpected shocks in the economy. The error (εit =vi+uit) is a composite error, where the individual effect (vi) summarizes unobserved company characteristics that are time-invariant, while the second term (uit) captures idiosyncratic shocks to the dependent variable. The appeal of such an error term decomposition derives from the opportunity it offers to control properly for unobserved individual company heterogeneity, by factoring out a different fixed effect for each one. OLS regressions on pooled data, by contrast, would estimate a single intercept for all the companies, thus omitting all those characteristics that are peculiar to each company and tend not to vary in a relatively short period of time. The omission of unobservable, yet relevant factors, would make the model misspecified from an econometric point of view, and would produce OLS biased (or inconsistent) estimates. Panel models can be applied hypothesizing individual effects which are fixed (FE) or random (RE)2. The fixed effects estimator is the natural candidate for application to our sample, since the companies belonging to it are specific (in the sense that their identification is relevant) and cannot be considered a random selection from a wider population. 5. Data and sample Our sample includes all listed firms on the Italian Stock Exchange, excluding the financial sector, in the period 2008-2009. The Italian market has been chosen because, due to the recent introduction of the IAS 1 2007 revised, comprehensive income value relevance literature lacks studies based on this market. To the best of our knowledge, there are few studies that examine CI value relevance (Bertoni et al., 2005, Azzali et al., 2010, Mechelli, 2011), but no study focused on the FCTA value relevance. Moreover, the selection of the Italian market allows us to test a value 2 The FE approach is conditional to the vi values and therefore it is appropriate when individuals in the sample are “particular” and cannot be considered as random extractions from a population. This happens, for example, when I indicates states or regions (as often occurs in macro economic panels), large businesses (eg. multinationals) industrial sectors. In all such cases, the inferences that we can make are necessarily conditional (and relative) to the individuals included in the sample. The case is different when the individuals in the sample can be considered as random extractions from a population: here, the individual characteristics become a component of the variability of the population and the inferences of an RE approach are therefore relative to the population itself. In short, one first reason for which an FE estimator can be preferred over the RE resides in the interest towards the vi. This takes place typically (and has sense) if the individuals in the sample are relatively reduced in number and have a specific nature, so that their identification is important. Notwithstanding this, there are situations in which the FE approach is preferable even if the number of individuals in the sample is relatively high and we are concerned with inferences regarding the population. This occurs when the individual effects and the explicative variables are correlated. relevance model on a financial market not yet fully investigated under this profile and which has features which are different in real terms if compared with the benchmark U.S stock exchange market, such as the small number of listed firms and the lower financial maturity of investors (Brealey et al., 2007). In accordance with previous studies, we excluded banks, insurance companies and other financial firms from our industry sample because disclosure requirement accounting rules reflect on the annual account content and would not allow for comparison of companies (Devalle, 2010). Since implementation of IAS 1 2007 revised began in 2009, and due to the consideration that our objective is to test the value relevance of as reported FCTA numbers, we consider only the two year period 2008-2009, the only period for which the as reported FCTA information is available. Information on share prices, book value and earnings are drawn from the Datastream database. Given that during our investigation we found that Datastream does not propose OCI related items, data related to the as reported FCTA has been “hand collected” from the financial statements of listed groups. After excluding financial firms, the following criteria have been adopted for the selection of the final sample: Sample firms should have enough data to compute required variables The book value of shareholder equity should be positive The firm’s fiscal year should end in December. This selection procedure yields 108 Italian firms. The panel is balanced and spans the years 2008– 2009. Table 1 shows the distribution of observations by industry, in line with the classification adopted by the Italian Stock Exchange. Table 1 - Sample distribution by industry sector Sectors No. % FTSE Italia All-Share Oil and Gas 1 1% FTSE Italia All-Share Basic Materials 1 1% FTSE Italia All-Share Industrials 36 33% FTSE Italia All-Share Consumer Goods 35 32% FTSE Italia All-Share Health Care 5 5% FTSE Italia All-Share Consumer Services 9 8% FTSE Italia All-Share Telecommunications 4 4% FTSE Italia All-Share Utilities 9 8% FTSE Italia All-Share Technology 8 7% 108 100% Total Table 2 reports the summary statistics of the variables that are employed in the estimations Variables June closing price Book value per share (BVPS) Earnings per share (EPS) Foreign Currency Translation Adjustment (FCTA) Dummy for negative EPS Assets per share (APSH) Mean 5.457 4.301 .375 -0.071 .327 4.188 SD 7.961 5.056 3.400 1.153 0.470 4.861 Min 0.051 2.771 -20.69 -16.310 0 .02 Max 61.45 39.12 30.32 3.284 1 38.09 6. Main results This section examines the incremental value relevance of as reported FCTA numbers and the incremental value relevance of the single components of as reported OCI numbers. Table 3 reports the results of the fixed effects panel model. All estimates are calculated with standard errors robust to heteroscedasticity. Table 3 – Fixed effects panel estimates Book value per share (BVPS) Earnings per share (EPS) Dummy for negative earnings Interaction_EPS Foreign Currency Translation Adjustment (FCTA) Assets per share (APSH) Interaction_FCTA Dummy_year Cons Number of observations R2(overall) F test F test (Eps and its interaction) F test (FCTA and its interaction) Equation (1) Coeff t-test 2.52** 2.95 3.24*** 0.77 0.31 0.13 -1.06 -3.61*** 3.19*** 4.71 -1.86* -1.98 -0.47 -3.26*** 1.78* 0.39 0.23 0.15 216 0.98 47.51*** -0.29 -3.4*** 4.2 3.18*** (*), (**), (***) denote statistical significance at the 10, 5 and 1% level, respectively As we can see in table 3, the two basic accounting variables in the Ohlson model, BVPS and EPS, are significant and vary in the predicted direction. In detail, we also verified the different valuation of negative earnings, tested through an F test for the joint significance of the two coefficients. The same procedure has been carried out for the FCTA interacted term, and both the FCTA term and its interaction term are significant. Its negative sign, consistent with Pinto (2005) and Louis (2003), means that assets may be thought as an hedge against exchange rate depreciations. Our research hypothesis regarding the incremental value relevance of FCTA is proved by the significance of the FCTA coefficient and by the significance of the F test, a statistical diagnostic which assesses the conjoint significance of the regression model’s coefficients. 7. Discussions This study has examined whether disclosure of FCTA numbers as required by IAS1 revised 2007 provided price-relevant information for investors’ decision making. Previous literature on FCTA value relevance provided mixed evidence, but previous studies must be interpreted with caution because of they do not employ panel data techniques, they do employ as-if numbers and they, with the exception of Pinto (2005), do not use an interacted model to allow the FCTA to vary conditioned on firm’s assets. In this paper, we have examined data for companies listed on the Italian Stock Exchange in periods immediately after the adoption of IAS 1 revised 2007. The idea is that there are statistically significant differences for investors when information is clearly disclosed. Recent archival research on the value relevance of OCI numbers has provided mixed evidence of the value relevancy of OCI numbers. According to Chambers et al. (2007) one of the potential reason for this is that these studies used mainly as if measures of OCI and its components in their tests of value relevance rather than as reported numbers from financial statements. Use of this data could have introduced a measurement error that could have affected inferences. Consistently with them, we use as reported FCTA numbers for Italian listed firms on the Milan Stock Exchange (excluding the financial sector) to avoid measurement error and provide evidence of its incremental value relevance. We provided evidence that the as reported FCTA is incrementally value relevant for Italian investors. These results also have implications for the current accounting practice of FCTA. The main issue is that the results of this study contradict the notion that foreign currency translation adjustments are mere ‘‘bookkeeping’’ entries and thus do not affect valuation. Therefore, ‘‘other items of comprehensive’’ income, of which foreign currency translation adjustments are the largest element for most firms (Dee, 1999), are a significant source of incremental value-relevant information for investors. As regards the two basic Ohlson variables, the BVPS is more value relevant with respect to earnings variables. A possible reason for the relative lesser relevance of the earning variable could be explained by the existence of the negative earnings for some companies in the sample. The study by Collins et al. (1999) suggests that, in the presence of loss firms, the role of BVPS as a proxy for expected future normal earnings is heightened because earnings are not useful in forecasting future earnings. The main limitations of the study lie in the small size of the sample and the narrowness of the period investigated, which should induce caution in interpreting the results, since our findings could be sensitive to the volatility of FCTA, as it is a component of OCI, to which several authors ascribe a lesser persistence with regards to the core earnings (Ohlson, 1999). Therefore, it is, at the best of our knowledge, the first study on the Italian stock exchange investigating the incremental value relevance of FCTA using the panel estimates method. One possible reason for the higher value relevance of FCTA in the Italian contest could be founded on the functioning of the markets. In fact, the main features of the Anglo-Saxon accounting system are principles-based and equity capital market-oriented. Managerial discretion over accounting recognition and disclosure has played an important role in this accounting system and it is likely that it could have had an impact on the recognition of CI and its components and therefore a significantly reverse effect on their potential link with firm value. In contrast, continental European countries such as Italy have adopted a more rules-based and credit capital market- and tax-oriented accounting system, where managerial discretion has played a less important role in deciding comprehensive income and its components. On the basis of this, consistently also with the literature that has found that the impact of adoption of the IAS/IFRS is greater in civil code than in common law countries (Morais and Curto, 2007; Agostino et al., 2010), we found confirmation for our idea that Italian investors could be able to understand and correctly use the information in a more efficient and effective way, compared to Anglo-Saxon investors. In the future, we need to verify the robustness of our findings, by enlarging the sample to other countries whose markets have features similar to those of the Italian market, by extending the range of years investigated, when data becomes available, also considering that the new IAS 1 revised 2010 will heighten the transparency of the disclosed information on CI, by comparing the as reported results with as-if results, to include in the valuation model the other OCI components. References Aggarwal, R. (1978), ‘‘FASB No. 8 and Reported Results of Multinational Operations: Hazard for Managers and Investors’’, Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, Vol. 1, No. 3, pp. 197–216. Agostino M., Drago D., Silipo D.B (2010). The value relevance of IFRS in the European banking industry. Review of quantitative finance accounting, published on line: DOI 10.1007/s11156-010-0184-1. Aliber R.Z. and Stickney C.P. (1975), ‘‘Accounting Measures of Foreign Exchange Exposure: The Long and Short of It’’, The Accounting Review, Vol. 50, No. 1, pp. 44–57. Arellano, M. (2003) Panel data econometrics, Oxford University Press, Oxford. Azzali S., Fornaciari L., Pesci C. (2010), “The value relevance of the performance of listed Italian companies following the introduction of the IAS/IFRS”, paper presented at the 4th edition of the Annual International Conference Globalization and Higher Education in Economics and Business Administration (GEBA), Alexandru Ioan Cuza University, Iasi, Romania, 21-23 October. Baltagi, B. (2005), Econometric analysis of panel data, third edition, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester. Barth M.E. and Clinch G. (2005), “Scale effects in capital markets-based accounting research”, working paper, Stansford University. Bartov E. (1997), ‘‘Foreign Currency Exposure of Multinational Firms: Accounting Measures and Market Valuation’’, Contemporary Accounting Research, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 623–652. Bartov, E., ‘‘Foreign Currency Exposure of Multinational Firms: Accounting Measures and Market Valuation,’’ Contemporary Accounting Research 14(4) (Winter 1997), pp. 623–652. Basu, S. (1997), The Conservatism Principle and the Asymmetric Timeliness of Earnings, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 24, Issue 1, 1997, pp. 3-37. Beaver W.H. and Wolfson M.A. (1982), ‘‘Foreign Currency Translation and Changing Prices in Perfect and Complete Markets’’, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 20, pp. 528–550. Bernard, V.L. (1995) “The Feltham-Ohlson Framework: Implications for Empiricists”, Contemporary Accounting Research, Vol. 11, pp. 733-747. Bertoni M., De Rosa B., Maffei M. (2007), “Comprehensive income under IFRS: evidence from a crosssectional analysis”, 3rd Annual Workshop, European Financial Reporting Research Group - Accounting in Europe, ESSEC Business School, Paris, France, 12-13 September. Biddle, G. and J.H. Choi (2006), “Is Comprehensive Income Useful?”, Journal of Contemporary Accounting and Economics, 2(1), June, pp. 1-32. Boatler R.W. (1992), ‘‘When Inflation is Not High Enough: Disappearance of Real Assets Under FAS 52’’, International Journal of Accounting, Vol. 27, pp. 262–266. Bragg V.E. (1997). Reporting Compehensive Income Florida CPA, September, 5-7. Braumoeller, B.F., Hypothesis, “Testing and Multiplicative Interaction Terms”, International Organization, Vol. 58, Issue 4, 2004, pp. 807-820. Brealey et al. Brealey R. A., Myers S. C., Allen F., Sandri S. (2007), Principi di Finanza Aziendale, Quinta Edizione, Milano, McGraw-Hill. Brimble, M. and A. Hodgson (2004), “‘The Value Relevance of Comprehensive Income and Components for Industrial Firms”, Working Paper, Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia. Cahan, S.F., S.M. Courtenay, P.L. Gronewoller and D.R. Upton (2000), “‘Value Relevance of Mandated Comprehensive Income Disclosure”, Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 27 (9) & (10), November-December, pp.1273-1301. Callaghan J.H. and Bazaz M.S. (1992), ‘‘Comprehensive Measures of Foreign Income: The Case of SFAS No. 52’’, The International Journal of Accounting, Vol. 27, pp. 80–87. Callaghan J.H. and Bazaz M.S. (1992), ‘‘Comprehensive Measures of Foreign Income: The Case of SFAS No. 52’’, The International Journal of Accounting, Vol. 27, pp. 80–87. Carlson R., Mooney K., Schwieger B. (1999). More Information On The Income Statement? National Public Accountant, 44, 1: 50-53. Chambers, D., T.J. Linsmeier, C. Shakespeare and T. Sougiannis (2007), “An Evaluation of SFAS n°130 Comprehensive Income Disclosures”, Working Paper, University of Kentucky, Lexington. Cheng, A., J. Cheung and V. Gopalakrishnan (1993), “On the Usefulness of Operating Income, Net Income and Comprehensive Income in Explaining Security Returns”, Accounting and Business Research, 23, n°91, pp.195-203. Collins D.W, Pincus M. and Xie H. (1999), “Equity valuation and negative earnings: the role of book value of equity”, The Accounting Review, Vol. 74, No. 1, pp. 29-61. Courteau, L. (2008), Valori di impresa e valori di bilancio (Firm’s values and accounting values), Milano, FrancoAngeli. Dechow, P.M., Hutton, A.P, and R.G. Sloan (1999), “An Empirical Assessment of the Residual Income Valuation Model”, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 26, pp. 1-34. Dehning B., Ratliff P.A. (2004). Comprehensive income: evidence on the effectiveness of FAS 130, The Journal of American Academy of Business, Cambridge, March: 228-232. Devalle A. (2010). Misurazione delle performance nel bilancio IFRS. Comprehensive income. dibattito internazionale e value relevance, Pearson Editore, Torino. Dhaliwal, D., Subramanyan, K. R. and Trezevant, R. (1999), “Is comprehensive income superior to net income as a measure of firm performance?”, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 26, no. 26, pp. 43-67. Feltham G.A., Ohlson J.A. (1995). Valuation and Clean Surplus Accounting for operating and financial activities. Contemporary Accounting Research, Vol. 11, pp. 689-731. Fitzsimmons A.P., Thomson J.W. (1996). Reporting Comprehensive Income Commercial Lending Review, 11, 4: 97-103. Giñer B., Iníguez R. (2006). An empirical assessment of the Feltham-Ohlson models considering the sign of abnormal earnings Accounting and Business Research, 36, 3: 169-190. Goncharov, I. and Hodgson, A. C. (2008), Comprehensive income in Europe: Valuation, prediction and conservatism issues, Annales Universitatis Apulensis Series Oeconomica, Faculty of Sciences, "1 Decembrie 1918" University, Alba Iulia, Vol. 1, Issue 10. Hayn C. (1995). The information content of losses Journal of Accounting and Economics, 20 (2): 125-153. Houston C.O. (1989), ‘‘Foreign Currency Translation Research: Review and Synthesis’’, Journal of Accounting Literature, Vol. 8, pp. 25–48. Jorion P. (1990), ‘‘The Exchange Rate Exposure of U.S. Multinationals’’, Journal of Business, pp. 331–345. Kanagaretnam, K., R. Mathieu and M. Shehata (2009). ‘Usefulness of Comprehensive Income Reporting in Canada’, J. Account. Public Policy, No. 28, pp. 349-365. Karathanasis G.A. and Spilioti S.N. (2005), “An empirical application of the clean surplus valuation models: the case of Athens stock exchange”, Applied Financial Economics, Vol. 15, pp. 1031-1036. Khodadadi, V. and Reza Emami, M. (2010), “Comparative assessment of Feltham-Ohlson sign-oriented & traditional models, International Research Journal of finance and economics”, Vol. 36, pp. 59-74 Kubota, K., Kazuyuki, S., and H. Takehara (2006). ‘Reporting of the Current Earnings plus Other Comprehensive Income: Information Content Test of Japanese Firms’, paper presented at the AAA 2006 Annual Meeting. Lin, S. (2006). ‘Testing the Information Set Perspective of UK Financial Reporting Standard N°3: Reporting Financial Performance’, Journal of Business, Finance and Auditing. Lin, S., Ramond, O. J., Casta J. (2007), Value Relevance of Comprehensive Income and Its Components: Evidence from Major European Capital Markets. American Accounting Association (AAA), International Accounting Section (IAS) Mid-Year Conference, 2-3 February 2007. Lo, K. and Lys, T. (2000), “The Ohlson Model: Contribution to Valuation Theory, Limitations and Empirical Applications”, Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance, Vol. 15, N0. 3, pp. 337-367. Louis H. (2003), ‘‘The Value Relevance of the Foreign Translation Adjustment’’, The Accounting Review, Vol. 78, No. 4, pp. 1027–1047. Luecke R.W., Meeting D.T. (1998). How Companies Report Income Journal of Accountancy, 185, 5: 45-52. Lundholm, R.J. (1995), “A Tutorial on the Ohlson and Feltham/Ohlson Models: Answers to some Frequently Asked Questions”, Contemporary Accounting Research, Vol. 11, pp. 749-761. Mechelli A. (2011). La value relevance del comprehensive income e dei suoi componenti: un’indagine sperimentale Rivista Italiana di Ragioneria e di Economia Aziendale, 3/4: 128-142. Naceur, S.B. and Goaied, M. (2004), “The value relevance of accounting and financial information: panel data evidence”, Applied Financial Economics, Vol. 14, No. 17, pp. 1219–1224. O’Hanlon, J. and P. Pope (1999). ‘The Value Relevance of U.K. Dirty Surplus Accounting Flows’, British Accounting Review, 31, 459-482. Ohlson, J. (1995), “Earnings, books value, and dividends in equity valuation”, Contemporary Accounting research, Vol. 11, pp. 661-687. Ohlson, J. (2000), Residual income valuation: the problems, Working Paper, New York University. Ohlson, J. A. and. Skroff, P.K. (1992), “Changes versus Levels in Earnings as Explanatory Variables for Returns: Some Theoretical Considerations”, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 30, No.2, pp. 210-226. Pinto J.A. (2005), “How Comprehensive is Comprehensive Income? The Value Relevance of Foreign Currency Translation Adjustments”, Journal of International Financial Management and Accounting, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 97-122. Pourciau S. and Schaefer T.F. (1995), ‘‘The Nature of the Market’s Response to the Earnings Effects of Voluntary Changes in accounting For Foreign Operations’’, Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 51–70. Schwarz, G., (1978), Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann. Stat. 6: 461–464 Sin S. and Watts E. (2000), “The information content of losses: shareholder liquidation option and earnings reversals”, AustrialianJjournal of management, Vol. 25, pp. 327-338. Soo B.S. and Soo L.G. (1994), ‘‘Accounting for the Multinational Firm: Is the Translation Process Valued by the Stock Market?’’, The Accounting Review, Vol. 69, No. 4, pp. 617–637. Stevens M.G. (1997). The new prominence of comprehensive income Practical Accountant, 30, 9: 59-62. van Cauwenberge P. and de Beelde I. (2010), A critical note on empirical comprehensive income research, Betriebswirftschaftliche Forschung und Praxis, 62, pp 82-101. Wang Y., Buijink W., Eken R. (2006). The value relevance of dirty surplus accounting flows in The Netherlands. The International Journal of Accounting, Vol. 41, No. 387-405. Whittington G. (2005), “The adoption of international accounting standards in the European Union”, European Accounting Review, 14, 1: 127-153.