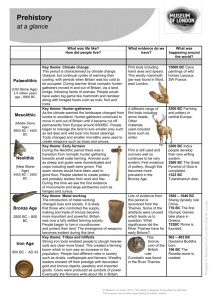

An Investigation of prehistoric settlement patterns

advertisement