ACCURACY AND CORRECTING MISTAKES

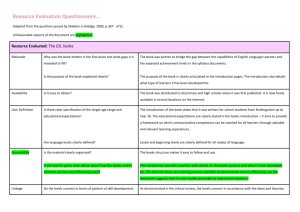

advertisement

ACCURACY AND CORRECTING MISTAKES A. How important is it to be accurate? What do you think? Would you agree or disagree with the following statements? 1. It’s not important for students to spell English words correctly, as long as their meaning is clear. 2. It’s not important for students to pronounce like a native speaker, as long as they are easily comprehensible. 3. It’s not important for students to use correct grammar, as long as they are getting their message across. If you answered ‘disagree’ to any of the above – can you say why? B. Achieving accuracy (Prevention is better than cure) Research indicates that to achieve accuracy, learners need... communicative language use + some explicit rule-learning + practice There are various theories about how accuracy is achieved: Rule-based practice (traditional, e.g. Murphy, 1985) The Input Hypothesis (Krashen, 1982) ‘Consciousness raising’ (Ellis, 2001) Task-based learning (Skehan, 1996) Probably the optimal answer is a combination of these models: Communicative tasks, with ‘time out’ for focus on form, including practice exercises Rule explanation, leading into both ‘mechanical’ and communicative practice But also time for: Communication on its own Focus on form on its own Language play (songs, chants, rhymes…) C. Correction (When prevention hasn’t worked) 1. Does it help? Truscott (1999, 1996) claims that correction in both oral and written work does not work: teachers correct inconsistently, sometimes wrongly; students are sometimes hurt by being corrected; students may not take corrections seriously; correction may interfere with fluency; learners do not learn from the correction. But these are inconsistent with… teacher intuitions; claims by learners themselves that correction helps (Harmer, 2005); empirical evidence that learners do learn from being corrected (Doughty and Varela, 1998). 2. What different kinds of correction are there? And which is the most effective? Which type of correction, on the whole, is better? (Lyster and Ranta, 1997; Lyster, 1998) Simple ‘recast’ is most often used, but leads to least ‘uptake’; Recasts may not be perceived as correction at all; The best results are gained from corrective feedback + some negotiation. Within communicative interaction, we try to make our corrections unobtrusive – so we use quick recasts, and don’t demand self-correction. But many of these may not be perceived as corrections, or even noticed! , so may be a waste of time! If we correct, we need to make sure ‘uptake’ has occurred, even if this slows things down a bit. 3. What are learners’ preferences? Learners want to be corrected. Learners feel corrective feedback is valuable (Harmer, 2005). Learners prefer explicit correction (but maybe not adults and more advanced learners, Harmer, 2005). Learners understand the value of repeating / rewriting the correct form. Learners do not, on the whole, like to be corrected by peers. Penny Ur 2006 2 4. When should we NOT correct? Perhaps we should not correct when a learner is focusing on communicating? Because it is: non-communicative, inauthentic; not appropriate to the aims of the task; distracting, disturbing. there is some evidence that learners want to be corrected at the moment they make the mistake (Harmer, 2005). But… We need to balance the benefit against the damage: which is more important: preserving the fluent process and communicative nature of the interaction? Or providing corrective feedback where it is needed to help learners improve their accuracy? There is no easy answer to this one! But it is clear that there is no absolute ‘rule’ about when not to correct, and that our decision will involve a lot of different considerations specific to the learner: the importance of encouraging fluency, the importance of encouraging accuracy, the confidence and self-image of the learner, the sheer number of mistakes D. Summary and conclusions Accuracy-oriented as well as communicative teaching of language We need to do all we can to make sure that as students are learning new language they learn it correctly; so we should provide opportunities for students to: learn rules: talk about the language (language awareness), including contrast with L1, and practise accurate production as well as: lots of communicative work: exposure to (correct) spoken and written language, communicative speaking and writing tasks Effective corrective feedback If after all this learners are still making mistakes, corrective feedback can help improve accuracy. Corrective feedback may be provided during communicative tasks. But recasts on their own are probably ineffective. The most effective corrective feedback occurs when learners actively participate in negotiation of the correction, to make sure that there is uptake. Penny Ur 2006 3 References and further reading Dekeyser, R. M. (1998). Beyond focus on form: Cognitive perspectives on learning and practising second language grammar. In Doughty, C., & Williams, J. (Eds.), Focus on Form in Classroom Second Language Acquisition (pp.42-63). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Doughty, C., & Varela, E. (1998). Communicative focus on form. In Doughty, C., & Williams, J. (Eds.), Focus on Form in Classroom Second Language Acquisition (pp.114138). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Ellis, R. (2001). Grammar teaching - Practice or consciousness-raising? In Richards, J. C., & Renandya, W. A. (Eds.), Methodology in Language Teaching. (pp.167-174). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Harmer, P. (2005). How and when should teachers correct? Research News: The Newsletter of t he IATEFL REsearch SIG, 15, 38-39. Krashen S. (1982). Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition. Oxford: Pergamon. Lyster, R. (1998). Recasts, repetition and ambiguity in L2 language discourse. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 20(1), 51-81. Lyster, R., Lightbown, P. M., & Spada, N. A. (1999). Response To Truscott’s ‘What's wrong with oral grammar correction?’. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 55(4), 457-67. Murphy, R. (1985). English Grammar in Use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Norris, J. M., & Ortega, L. (2001). Does type of instruction make a difference? Substantive findings from a meta-analytic review. Language Learning, 51, Supplement 1, 157-213. Skehan, P. (1996). A framework for the implementation of task-based instruction. Applied Linguistics, 11, 38-62. Spada, N. (1997). Form-focussed instruction and second language acquisition: A review of classroom and laboratory research. Language Teaching 30(75): 73-85. Truscott, J. (1996). The case against grammar correction in L2 writing classes. Language Learning, 46, 327-369. Truscott, J. (1999). What's wrong with oral grammar correction? The Canadian Modern Language Review, 55(4), 437-56. Ur, P. (1988). Grammar Practice Activities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Willis, J. (1996). A flexible framework for task-based learning. In Willis, D., & Willis, J. (Eds.), Challenge and Change in Language Teaching (pp.52-62). Oxford: Heinemann. Penny Ur 2006 4