A Biographical Portrait Of Private Sector Professional Managerial

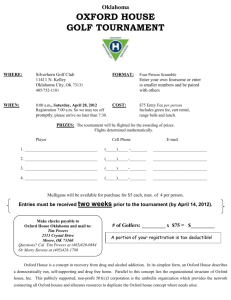

advertisement