Cemetery-Guide-v5-

advertisement

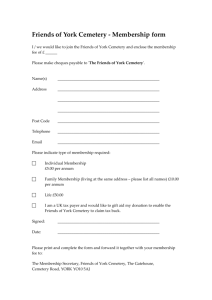

Discover Crowsnest Heritage Crowsnest The railway community that once straddled the provincial border is almost completely gone now. It is rumored that railway workers (1897 - 1898) who succumbed to a cholera outbreak were buried near here, but there is no official record of either a cemetery or a cholera outbreak. The story persists in local folklore, but all efforts to locate the cemetery have failed. If it existed, it may have been located at the north end of Summit Lake, and been obliterated during the construction of Highway 3 or the natural gas pipeline. Pamphlet produced by the Crowsnest Heritage Initiative Heritage Cemetery Guide Crowsnest Pass Doors Open & Heritage Festival Cemeteries of The Pass Within ten years of the arrival of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1898, a dozen coal-mining settlements were underway. Most had their own cemeteries, and some had more than one. With the dangers of mining and its associated hard life, the cemeteries of the Pass began to fill somewhat earlier than you might find in more genteel communities. Some of the cemeteries in this Guide are over a hundred years old, although many of the older burials are no longer marked. Catholics had their own cemeteries, or sections within cemeteries, usually named after the local Catholic church. Non-Catholic cemeteries are often called Union cemeteries. The cemeteries in this guide are ordered by community, approximately east to west. A general location map can be found in the centre of this pamphlet. Please control your pets and use respect when visiting these historic cemeteries. 1. B-15-9,10. Ukrainian immigrants Thomas (1889-1962) and Lena (1898-1981) Gushul professionally photographed scenes of everyday life throughout the Crowsnest Pass for several decades. Their restored Blairmore studio is a community landmark. 2. B-7-18. Andy Good (1873-1916) was a well-known outfitter and outdoorsman who owned the Summit Hotel on the Alberta/BC border between 1900 and 1915. Only the base of his grave marker remains. 3. The oldest graves in this cemetery are located here, in Section D. Many of the markers are now missing. 1. The oldest graves in the Catholic cemetery are near the front (east end), though many of the original wood markers are gone. 2. A-6-2. This ornate, fenced monument is for teenager Tony Nicholas (1910–1929) who died at Lundbreck Falls. Passburg The settlement of Passburg was established next to the Leitch Collieries, and began to fail when that facility shut down in 1915. Although the town is gone, the cemetery is still used. It is located about a kilometre northwest of the Leitch Collieries Historic Site. Drive to the Crowsnest Pass east portal municipal sign on Highway 3, about two kilometres west of Leitch Collieries, then turn north and follow the road back east past the campground for 1.4 kilometres. Hillcrest This is the best-known cemetery in Crowsnest Pass, as it includes the mass grave of the victims of the Hillcrest Mine Disaster of 1914. Within the same cemetery are Catholic and Masonic burial areas. To find the Hillcrest Cemetery, take the Hillcrest west access off Highway 3, cross the bridge, and turn right immediately after the Y in the road. The cemetery entrance is signposted, and is also part of the Crowsnest Pass Heritage Driving Route. 3. A-1-1. Joseph Homenick (1872-1910) and Mike Yagos (1882-1910) were both killed in a Coleman mining accident. 4. B-7-5. An attractive monument to Joseph Kliz (18861918) incorporates glass circles. At the cemetery parking lot one can find the Hillcrest Mine Disaster Millennium Memorial, and within the cemetery is a short interpretive walk. Hillcrest Cemetery is a Provincial Historic Resource. 4. B-16-3. A union activist and member of Blairmore’s ‘communist’ town council in the 1930s, Joe Krkosy (19101944) was denied funeral services by the local Catholic priest and was buried in the Union cemetery. Three thousand people attended his funeral. 5. B-10-31. Annie Dunlop (1865-1945) lost all three sons in World War One; only her husband, who was too old for active service, returned. The Dunlop guns in Frank are named after the family. 6. B-10-24. This row of Chinese markers includes the names of their birth villages, written in sinograph characters. Coleman Both cemeteries in Coleman are adjacent to each other, and are located on the south side of 27th Avenue at about 79th Street. You can access the area by turning north off Highway 3 and following either 86th Street (signposted Highway 40) or 81st Street, and winding your way up to 27th Avenue. 1. Old Masonic section (1914 - 1948) 2. 1910 – 1920 3. Hillcrest Mine Disaster mass graves, 1914 4. 1915 – 1920 5. 1930s 6. 1940s 7. 1930 - 1950 The Union Cemetery is above the Catholic cemetery. The Catholic cemetery was probably established in 1909 and was named after the Holy Ghost Catholic Church (renamed the Holy Spirit Catholic Church). This was the first Catholic church in the Pass (1905) and the building, now a coffee house, is well worth visiting. Bellevue St. Cyril's (sometimes called Our Lady of Lourdes) Catholic Cemetery is located just to the east of the Frank Slide and is visible from Highway 3. Take the Bellevue centre access road north from Highway 3 and turn left at the first opportunity. The cemetery dates to 1929 and was named after St. Cyril's Catholic Church which served Bellevue from 1915, and is now privately owned. The oldest marked grave is dated 1936. 1. B-1a-9 to 13. Reuben Steeves (1860-1908) was a prominent Frank businessman who owned the Imperial Hotel and the brick yard. Steeves drowned under mysterious circumstances while on a duck-hunting trip. To find the picturesque Bellevue Union Cemetery, drive to 215th Street in Bellevue, then drive or walk up 27th Avenue along an unimproved road under power lines for 500 metres. This cemetery was closed in part due to spring flooding. Its oldest marked grave is dated 1918. Frank 2. B-1-26 and 27. Joe Little (1853-1942) was one of Blairmore’s first residents. Reclusive and enigmatic, he had fingers in every pie, and once even owned the land that the Blairmore cemeteries are on. His brother Samuel (1848-1929) was a veteran of the Fenian Raids, an Irish American invasion of eastern Canada in 1866-1867. The cemetery at Frank was covered by the Frank Slide in 1903, only two years after the founding of the town. It was located east of the Frank Slide Interpretive Centre just past their parking lot, and is now underneath the boulders and rubble of the northern edge of the slide. 3. B-7-26,27. After Dr. Malcolmson failed to save his own daughter Beatrice (1902-1903) from diptheria, he had to dig her grave himself because of a miners’ strike. Malcolmson built a hospital in Frank in 1902 which had one 0f Alberta’s first x-ray machines. At least seven persons died in Frank between 1901 and April 1903, but it is not known how many were buried there. It is curious that the citizens of Frank did not start another cemetery after the Slide, despite the town's continued growth. After 1903, Frank’s residents were buried in Blairmore. The Frank Slide itself killed about ninety people, whose bodies were never recovered. In 1922, a minor realignment of the old graveled road through the Slide uncovered unidentifiable human remains, which were reburied at the side of the road. They were possibly the remains of Mrs. Clark and her five children who were asleep in the house closest to this site at the time of the Slide (4:10 am, April 29, 1903). A memorial was placed there on the fiftieth anniversary of the slide, to commemorate the 1922 reburial and all other persons killed in the slide whose bodies were not recovered. Two survivors of the slide, Delbert and Gladys Ennis, also chose to have their ashes scattered at this site. To find this memorial, drive the graveled road that runs through the Slide between the original Frank townsite (now an industrial park) and the Hillcrest west access road; the memorial is at the western edge of the slide. This historic 1906 road is also part of the Crowsnest Pass Heritage Driving Route. Information on the approximately ninety people killed by the slide is available at the Frank Slide Interpretive Centre. Lille The long-abandoned coal town of Lille is accessible by hiking the 6.3km (one way) Lille Heritage Trail. All of the buildings were removed, leaving only a few house imprints and some commercial/industrial foundations. Lille townsite is a Provincial Historic Resource, and no artifacts should be disturbed. 4. B-9-1 and B-11-20. The Drain brothers, Duncan (18671942) and Daniel (1862-1918), gave up railroading to become two of Blairmore’s early businessmen, operating the Blairmore Hotel, a livery stable, and a construction business. Drain Brothers Construction Ltd. is still based in Blairmore but now provides oilfield services. 5. B-16-21. In 1911 Italian immigrant Charles Sartoris (1886–1975) was the stable-boss for the mine in Frank, but soon became a self-made success in lumber, horse livery, automobile sales, construction, ranching and real estate. Blairmore Blairmore’s cemeteries were also used by Frank after 1903 and include many locally-significant graves. All three cemeteries are adjacent to each other, and can clearly be seen above the north side of Highway 3. Access is opposite (north) of the Blairmore centre access road; immediately turn east and follow the road for a few hundred metres to the two oldest cemeteries. St. Anne's Catholic Cemetery is encountered first. Follow the road further east up the hill to the Old Union Cemetery. The New Union Cemetery is also nearby, and was opened in 1975. 1. A-13-5. Henry Gibeau (1865-1951) was the Canadian cousin of Samuel Gebo, the co-founder of the mine and town of Frank. Henry and Samuel’s fathers were brothers, and their mothers were twin sisters. Henry gave up the wholesale liquor business when he became disgusted with the widespread drunkenness in Frank. 2. A-9-28. French-born Jules Charbonnier (1877-1942) came to Blairmore in 1913 as general manager of West Canadian Collieries. He actively supported mine rescue competitions and was a major patron for many Pass sports teams. 3. B-8-39. George Bond (1864-1951) arrived in Frank just one day before the Frank Slide, and was one of its better-known chroniclers. Lille's small overgrown cemetery is located in the woods some 800 metres southeast of the townsite. It is not marked, and cannot be seen from the trail, but the cemetery is occasionally visited so a track may be visible. The Lille Cemetery was probably used for seven or eight burials between 1905 and 1910. Only one grave marker from this period is currently visible, a nice white stone monument to Mrs. Alice Petiot who died in 1907. A metal plaque affixed to a tree commemorates James Vance Patera who died in 1982. Mr. Patera was born in Czechoslovakia in 1903 but grew up on his family's homestead near Lille between 1908 and 1918.