Different countries, similar challenges?, Sergiu Gherghina

DIFFERENT COUNTRIES, SIMILAR CHALLENGES?

A Comparative Assessment of Immigrant Political Participation in Western Europe

Sergiu Gherghina

Research Unit “Democratic Innovations”

Institute of Political Science

Goethe University Frankfurt gherghina@soz.uni-frankfurt.de

Paper prepared for presentation at the 3 rd Research Conference

“Immigration, Incorporation, and Democracy”

Vienna, 14-15 November 2013

Abstract:

The existing research on immigrants’ political participation has paid little attention to crossnational comparisons between first-generation immigrants coming from one country. To fill this empirical void, this paper identifies the determinants of Romanian labor migrants’ political participation in France, Germany, Italy, and Spain. It argues and tests the effect of five main determinants related to individual orientations, attitudes, social interaction, and resources. Data comes from a web survey conducted in the summer of 2013. The empirical results show that, with small country-level variations, the political participation is a function of membership in organizations, a longer period of stay in the country of residence, and the size of immigrants’ social network. In addition, education and gender are good explanations for the engagement in politics.

Introduction

There is a general consensus in the literature that political participation is a fundamental component of democracy. It is both a right offered to the people and a practice that enhances the legitimacy and stability of the political system. In this context, over the last decades increased attention has been paid to the political involvement of those individuals who became new members of the polities in which they reside. Accordingly, the political participation of immigrants has been an intriguing topic approached from various angles. So far, previous research focused on the patterns of political participation (Cain et al., 1991;

Jones-Correa, 1998; Hirschman et al., 1999; Bueker, 2005; de Rooij, 2012), its forms (Finifter and Finifter, 1989; Tam Cho, 1999; Garcia-Bedolla, 2000) or determinants (McAllister and

Makkai, 1993; Arvizu and Garcia, 1996; Leal, 2002; Barreto and Munoz, 2003; Gerber et al.,

2011; Ruedin, 2011). So far, most empirical analyses used a single-case study approach, compared immigrant groups within the same country, or investigated the behavior of different immigrant groups across several countries.

However, little attention has been paid, especially in Europe, to the cross-national political participation of first-generation immigrants belonging to the same group (i.e. coming from the same country). This paper fills this empirical void in the literature and compares the political participation of Romanian immigrants in four West European countries (France, Germany, Italy and Spain). The analysis focuses on several types of political participation (i.e. voting, campaign involvement, participation in protests or petition writing) and it is driven by the following question: what are the factors that enhance the immigrants’ political participation? The quest for an answer involves quantitative analysis at individual level. The ordered logistic regression tests for the explanatory power of five main independent variables: time spent in the host country, social network within the group of immigrants, associational behavior, perceived discrimination, and media consumption. The general and country-level models include controls for gender and education. The used dataset is original and consists of 1,358 respondents to a web survey conducted in June-

August 2013.

The focus on labor migrants with major flows around the date of their countries’ accession to the EU (i.e. 2007) is not accidental. So far, most of the literature has focused on the political behavior of immigrants who live for a few decades in the country of residence or who have naturalized. At the same time, some findings reveal that migrants were often

1

oriented towards achieving short-term economic goals and not very interested in political participation. By examining immigrant participation in the initial stages of residence, this paper makes two major scientific contributions: it sheds light on potential factors shaping the initial likelihood of participation and seeks to understand how the incorporation of immigrants into the politics of their country of residence takes place.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. The following section reviews the literature on participation, conceptualizes the types of participation and briefly explains the approach used in this study. The second section discusses the potential determinants for the political participation of ethnic migrants and formulates several testable hypotheses. Next, the research design is presented with an emphasis on data, variable measurement, and methodology. The fourth section includes a detailed discussion of the bivariate and multivariate empirical findings. The conclusions summarize the key results, discuss the implications of this study and elaborate on avenues for further research.

Political participation and its determinants

The extensive attention dedicated to political participation in the literature is proportional to its conceptual complexity. The definitions of political participation have been gradually altered over time as a consequence of richer content and expanded meaning.

Defining and conceptualizing political participation

More than four decades ago Pateman (1970) argued that political participation occupied a minimal role in the theories of democracy. Until then, participation has been equivalent to electoral participation (i.e. voting), thus reflecting the concerns and long efforts for franchise enlargement, and the elitist theories with an emphasis on a limited role for citizens

(Schumpeter, 1942; Sartori, 1962). According to the latter, citizens were expected to support or disagree with elites’ decisions and the only way to do this was through vote. The definition of political participation given by Verba and Nie (1972: 2) reflected this perspective: “Political participation refers to those activities by private citizens that are more or less directly aimed at influencing the selection of governmental personnel and/or the actions they take”. Accordingly, citizens had a voice only when they had to choose between representatives and support their policies. In their attempt to broaden the scope of political participation, Verba et al. (1978: 47) argue that while voting remains the primary way for

2

citizens’ involvement in the political system, participation can also take place in-between elections “when citizens try to influence government decisions in relation to specific problems that concerns them”. Teorell et al. (2007) explain how both these definitions – although enlarging the elitist view of participation through the possibility to influence policies – continue to remain narrow as they refer exclusively to government policies.

This limitation became obvious in light of several empirical developments. An increasing amount of studies have shown that ordinary citizens have used various means to influence more types of political outcomes not only the state policies (Parry et al., 1992;

Browning, 1996; Budge, 1996; Bimber, 1999; Fishkin et al. 2000). Following the diversification of participatory activities, a re-conceptualization of the notion appears necessary. Parry et al. (1992: 16) account for different outcomes and define political participation as ““action by citizens which is aimed at influencing decisions which are, in most cases, ultimately taken by public representatives and officials”. Brady (1999) takes one step further, broadens the spectrum of outcomes, and considers that political participation is “action by ordinary citizens directed toward influencing some political outcomes”. His perspective does no longer confine political participation to particular sets of citizen activities and outcomes. At the same time, participation is not oriented solely towards public officials and their decisions, but takes into account other institutions (e.g. interest groups that may influence policies. In their approach, Teorell et al. (2007: 336) strengthen the idea of any political outcomes, sometimes independent from government personnel or state agents.

This paper subscribes to these comprehensive definitions of political participation; accordingly, it also accounts for extensive types of participations. Verba et al. (1978) identified four general modes of political action: voting, campaign activities, contacting public officials, and cooperative or communal activities (with a focus on the issues in the local community). Teorell et al. (2007) and Dalton (2008: 34) added two new types: protests and other forms of contentious politics, and signing petitions 1 . Wider understandings of modes of participation include the new social movements or political violence (Urwin and

Patterson, 1990; Parry et al. 1992; van Deth, 1997). This broad range of activities has led to a conceptual separation between the conventional and unconventional types of participation

(Peterson, 1990). The conventional category includes the electoral participation and the

1 Dalton also refers to e-petitions since Internet plays an important role in his argument

3

actions associated with it: voting and electoral campaign activities. Unconventional participation refers to the rest of activities connected to contacting officials, protesting, and political violence. In spite of this useful division, earlier studies have shown that the boundaries of the different types are unclear neither from a conceptual (Richardson, 1993) nor from an empirical (Parry et al., 1992) point of view.

In light of such conceptual diversity, this study focuses on six types of political participation: voting (in local, national, and European elections), electoral campaign activities, protest activities, contacting politicians, petition signing, and political discussions 2 .

At the same time, given the above mentioned overlaps, this study does not distinguish between conventional and unconventional forms of participation. It also treats the types as having equal weight and concurrent; thus, it does not follow the hierarchical conceptualization of Milbrath (1965).

3

The focus on individuals

In addition to the dependent variable of this study, it is important to briefly explain the focus on the individual level (i.e. citizens’ motivations, opinions, and resources). The goal of this paper is to understand why immigrants belonging to a particular group (i.e. Romanians in four West European countries) engage in politics. Although carried in a specific setting and context, political participation has been always conceptualized as an individual activity.

Consistent with this approach, the central argument of this paper is built primarily at individual and not at group level. Thus, it seeks to identify drivers for participation within the ethnic group and has no interest in investigating group-based issues such as ethnic claims or policies. Thus, comparisons are made within the group of Romanian immigrants – across several countries – and not with other groups of immigrants or citizens of the host countries.

The key premise of this approach is that individual beliefs, motivations, and resources influence the decision to participate. It builds on idea of political equality in the participation process from an individual perspective (Verba, 2003), leaving aside the inequalities that may emerge from differences between various groups.

2 This paper accounts only for the political discussions in an organized setting. There are good theoretical reasons to leave out the talks with members of the family (for details, see Teorell et al. 2007).

3 Milbrath (1965) sees political participation as cumulative and argues that people get involved first in the top behaviors. According to him, those who participate in the top activities are also likely to perform in those lower in rank.

4

This has been common for several decades in the research on participation. Milbrath and Goel (1977) illustrate that there are several instances in which individual traits are likely to affect behaviors. According to them, individual motivations gain priority when reference groups have conflicting points of view, when social roles are ambiguous and unknown, or when previous experience gets into conflict with current issues. The importance of individual resources and motivations – and the existing link between them – has been emphasized in several other studies (Rosenstone and Hansen, 1993; Verba et al., 1995; Dalton, 2008). To strengthen these findings, a significant body of literature indicates that individual subjective motivations foster political participation even in authoritarian regimes (Schulz and Adams,

1981; Bahry and Silver, 1990; Manion, 1996; Chen, 2000).

Why do immigrants engage in political participation?

Earlier research on political participation at micro level (i.e. individuals) has identified several explanations for why people engage in politics. There are no theoretical reasons to believe that the general mechanisms are not applicable to the specific group of immigrants; the latter get involved in politics just like other citizens of the country of residence and the determinants are likely to be similar. This section provides arguments for the explanatory power of five variables: length of stay, social network, associational behavior, perception of discrimination, and media consumption.

To begin with, social stability or social connectedness in the words of Leighley and

Vedlitz (1999) can act as a catalyst for political participation. Individuals who live for a longer period of time in a community develop stronger social, economic or political interests. In turn, these interests are drivers for political participation. The Romanian labor migrants are the usual suspects to identify the existence of such a relationship. In their case, two additional mechanisms are at work. First, the time spent in the host country helps them to accustom to political systems that allow meaningful participation. All four West European countries provide their citizens with multiple democratic ways of expressing their (political) will. Romanian immigrants may theoretically know that political participation in the host country is possible, but they can become aware of their options for participation only gradually. Second, some of the Romanian migrants had participated in politics in their countries of origin before their departure. A longer period of stay in a new country can

5

determine them to practice their old activities although the environment is different.

Combining these three reasons there are reasons to expect that:

H1: Immigrants with a longer stay in the host country engage more in politics than the rest.

A large body of literature pointed in the direction of social networks as good predictors for political participation. The social connections with people similar to oneself and interactions expose individuals to varied and greater supplies of information. In turn, this information facilitates the understanding of politics and enhances the possibilities to get involved

(Huckfeldt and Sprague, 1995; Huckfeldt, 2001). The core argument is that conversations between network partners facilitate the access of people to political information from the surrounding environment. When this information is of political nature, people are likely to become more active in politics. Within the network, people can gain access to different sets of politically-relevant information compared to that achieved on their own (Huckfeldt, 2001;

Mutz, 2002; McClurg, 2003). Apart from the information nexus, the influence of social networks on political activity is exerted also through mobilization. There are a few instances in which political leaders use social contexts to mobilize mass participation (Rosenstone and

Hansen 1993; Verba et al. 1995).

These mechanisms indicate that broader social networks are conducive to higher levels of political participation. The situation of immigrants matches this general perspective.

In their case, the needs for information about their new social environment (i.e. host country) are quite high. The contact with peer immigrants with similar ethnic background – for the ease of communication – can foster a better understanding of how things work. Since political activities were often part of immigrants’ lives in their home country, the social networks also facilitate access to opportunities for participation during their stay in the host country. Broader social networks mean more experiences and more perspectives.

Consequently, I expect a positive effect of the social network size on political participation.

H2: The immigrants with an extensive social network are likely to participate more than the rest.

6

Somewhat related to the previous logic behind H2, civic engagement has been often considered a valid explanation for political participation (Verba and Nie, 1972; Rosenstone and Hansen, 1993; Verba et al. 1995). There are at least three mechanisms at work: 1) the development of skills necessary for participation; 2) the provision of alternatives for deprived citizens and 3) a reflection of a general activism. First, the membership in organizations (political or non-political) can enhance the political education and develop the communication abilities necessary for the involvement in politics. People can be socialized with the pro-participatory values and to learn specific skills that may lead to further participation (Leighley, 1996; Teorell, 2003). Although the organizations to which citizens belong do not have (many) political activities, the discussions with other members may have a political dimension. At the same time, various organizations encourage their members to get politically involved in one way or another. Classic examples in this respect are the church organizations that advise their members to support the Christian parties or the trade unions that have traditionally stood by the social democratic parties.

Second, Verba et al. (1978) have argued that membership in organizations partly compensates for scarce socio-economic resources. This favors the political participation though the use of organizational resources, thus making it independent from the individual resources. As a result, the membership in voluntary organizations increases the individual level of political participation (Verba and Nie, 1972). Third, following the core argument of

Putnam (1993), citizens who get involved in organizations are likely to be more interested in the societal problems. Consequently, their propensity towards political participation is higher than that of their fellow citizens. In addition to these mechanisms, the membership in organizations can play a relevant role for immigrants with respect to their adaptation and integration in society. The organization can be a socializing arena for interactions with people having similar concerns. It is the place where first contact with the problems in the host societies is established. In this respect, that is the place where the preconditions for political involvement are met. This is particularly the case with civil organizations where other immigrants from the same group can be found. In light of these arguments, I hypothesize that:

H3: The members of voluntary organizations are likely to participate in politics more than the rest.

7

In addition to these factors, the perception of treatment in the host society may affect political engagement. In recent times media reports have often presented instances in which immigrants were mistreated. In particular, the tensed relationships between some

Romanian immigrants and citizens of the host country or state authorities in France, Italy, or

Spain have been extensively covered in the national and international news. Earlier research has indicated that the extent to which people feel welcome in a society can shape their participation. However, the empirical evidence is mixed, revealing two different possibilities.

On the one hand, Schildkraut (2005) finds that perceptions of discrimination against oneself discourage Latino immigrants in the United States to engage in politics; this is particularly the case with those who identify primarily as American. They feel rejected by society and this leads to alienation and lack of involvement. On the other hand, DeSipio (2002) shows how the Latinos who perceive personal discrimination in the United States get engaged more in activities.

While both perspectives are legitimate, there are reasons to believe that DeSipio’s findings may be replicated in the case of Romanian immigrants in Western Europe. When perceiving adversarial attitudes oriented against them, labor migrants are unlikely to exhibit alienation; there are rare examples of migrants who identify with the host country a few years after their arrival. On the contrary, the common response is to fight back. All these persons come from a society in which they have been treated as equal citizens. Once arrived in the current country of residence they expect nothing less; as soon as they perceive discrimination, they may want to mobilize and alter this situation. One of the most convenient ways to do is through political participation that provides direct access to decision-making. Summing up, the perception of discrimination is expected to have a positive effect on political participation:

H4: Immigrants who perceive personal discrimination participate more than the rest.

Some of the previous mechanisms made references to the importance of information for political participation. Information is crucial for participation because it reduces the costs – a key factor in deciding whether to get involved or not. Media is the primary source for information in general and political information in particular. Referring to the latter, the role

8

of media becomes prominent during electoral campaigns when voters need to know about the political programs, ideologies, and issues promoted by various candidates. So far, an extensive body of literature has shown a positive impact of media use on political knowledge

(Drew and Weaver, 1998; Scheufele, 2002; Bimber and Davis, 2003). In turn, knowledge influences involvement: empirical evidence has shown that individuals who closely follow the development of the public affairs are more involved in comparison to the rest of the citizens (McLeod et al. 1999). On the basis of this mechanism, there is no surprise that earlier findings pointed to a strong correlation between political participation and news interest and consumption (Almond and Verba, 1963; Putnam, 2000; Shah et al., 2005). A similar effect of media consumption on participation is expected in the case of Romanian immigrants. In their case, through the supplied information, the media leads to familiarity with a new system. Such a nexus may create the necessary incentives for participation:

H5: Heavy media consumers are likely to participate more than their peers.

Control variables

Previous studies have revealed that the variables associated to the socio-economic status

(SES) are drivers for political participation (Pateman, 1976; Milbrath and Goel, 1977; Dalton,

1988; Conway, 1991; Verba et al., 1993; Mishler and Clarke, 1995; Verba et al. 1995; Nie et al. 1996; Kitschelt and Rehm, 2008). Among these, education has been explicitly emphasized as the most important component of SES (Peterson, 1990; Conway, 1991; Leighley, 1995; Nie et al. 1996). High levels of education foster a better understanding of politics (i.e. higher analytical skills), makes people aware about ways to promote their interests, and stimulate citizens’ interest in politics. Similarly, earlier research has revealed the importance of gender in structuring political participation (Verba, 1978; Jennings 1983; Schlozman et al. 1993;

Verba et al. 1993; Garcia-Bedolla, 2000; Burns et al. 2001; Inglehart and Catterberg, 2002;

Inglehart and Norris, 2003). Consequently, this study controls for levels of education and gender.

4

4 The study has also tested for other SES factors (e.g. occupation, interaction effects between age, education and occupation) and knowledge of the language in the country of residence. They were not reported since they had no strong or significant effect.

9

Research design

Data for hypothesis testing comes from a web survey conducted among the Romanian immigrants between 1 June and 15 August 2013. Romanian immigrants make the subject of this study due to their significant presence in several European countries. The survey focused on the immigrants from the most popular Western destinations: France, Germany,

Italy and Spain. From a methodological perspective the selection of these four countries is adequate for two reasons. First, there is great variation in the respondents’ profile, their distribution being different both across the independent variables of this study and in terms of socio-demographic variables (e.g. age, education, gender, occupation, area of residence and of origin, and experience of migration).

5 Such variation corresponds to the broad brush reports presented in the Romanian media about migrant workers in Western Europe; they often emphasized differences in socio-economic status (e.g. occupation, education). The absence of official statistics regarding the Romanian immigrants abroad does not allow testing the profile of the respondents in the web survey sample against the entire universe.

Second, the selected countries are fairly similar with respect to their political development

(i.e. established democracies) and to the provision of extensive opportunities for popular participation. While earlier studies have shown that the wider environment of national politics can shape political participation (Lijphart, 1999; Teorell et al., 2007), the above mentioned resemblances make a constant out of the national layer and allow the focus on individual traits.

Since the survey addressed both legal and illegal immigrants – with reference both to their residence status and work conditions – there has been no probability representative sampling. The respondents were neither pre-selected nor part of a pool of available individuals. Instead, three channels were used to maximize the number of answers to the questionnaire: 1) messages on facebook groups and discussion forums of Romanians abroad;

2) e-mails sent to representatives of Romanian associations and organizations and 3) e-mails sent to individuals recommended by respondents (i.e. snowball). Consequently, the analyses and findings presented in this paper are limited to the respondents to the web survey.

5 A detailed account of this variation is available in the web survey report (in Romanian) at: http://fspac.ubbcluj.ro/ethnicmobilization/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/Research-report-Romanian-migrantswebsurvey1.pdf, last accessed 2 November 2013.

10

In total, there were 1,358 respondents who started the web survey. Out of these 831

(61%) answered all the questions. Although the survey had no age limit – due to a more general interest in the situation in schools – there were only three respondents under the age of 18. The abandon has been random without any particular question leading to defection. The distribution of complete answers across the four countries was the following

(in brackets is the percentage reported to the number of initial respondents who accessed the survey in that particular country): 303 in France (62%), 206 in Germany (56%), 138 in

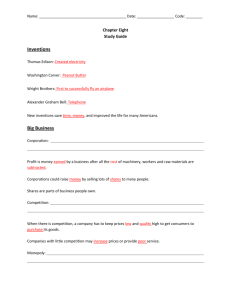

Italy (63%) and 184 in Spain (65%). Figure 1 depicts the evolution of the total number of answers during the data collection period.

Figure 1: The dynamic of web survey responses (June-August 2013)

Out of the total number of collected responses 77% resulted from the ads posted on facebook groups and discussion forums and 23% were generated via the e-mails sent from the web survey platform. The survey turnout has been reported by the server on a weekly basis with data available for every Sunday. The peaks correspond to the period when new emails (in the case o the snowball method) or reminders were sent.

Variable operationalization and methods

The dependent variable is a count measure of political participation with eight components: voted in the national elections in Romania, voted in local elections in (host country), voted in the European elections, took part at a protest or demonstration, contacted or visited a politician, signed a petition (online or on paper) with a political purpose, volunteered in a

11

political campaign, and took part in political discussions in an organized setting. It was operationalized as the answer to the following question: “During your stay in (host country) how often have you…. ?”. The available answers were: “never”, “once”, “several times”,

“often” and “every time I had the opportunity”. The answer provided to each of the political participation items has been coded dichotomously with a value of 0 for the answer “never” and 1 for any other answer (i.e. participation at least once). These were summed to produce a measure running from 0 to 8. The final four categories were then collapsed into a single category to avoid small response category sizes. The final measure of political participation runs from 0 to 4 where 0 indicates participation in none of the specified types, 1 corresponds to one type of participation, 2 to two types, 3 to three types, and 4 to four or more types.

6 The frequency of this variable is presented in Table 1, both pooled and at country level.

Table 1: Frequency of political participation among respondents (%)

Variables

No participation

One type of participation

Two types of participation

Three types of participation

Four or more types of participation

N

General

31

18

15

12

24

855

France

32

20

19

12

17

310

Germany Italy

34 31

22

12

13

19

211

12

14

11

32

144

Spain

25

16

12

13

34

190

There are five explanatory variables of interest. The first, length of residence, is coded on a five-point ordinal scale that reflects the answers to the question “How long have you lived in

(host country)? We are interested in the total period, not only the uninterrupted period of time”. Available answers were: “less than six months”, “between six months and one year”,

“between one and three years”, “between three and six years” and “more than six years”; they were coded ascending. The social network variable is an ordinal variable coded on a sixpoint scale. It is based on the answers to the question “What is the approximate number of

Romanians you know in (host country)?”. Available answers (coded ascending) were:

“none”, “one to 20”, “21 to 50”, “51 to 100”, “101 to 200” and “more than 200”. The membership in organizations is a dummy variable (0 for non-membership) based on the

6 When creating the index I have checked if one type of political participation is more present in the final categories; the result was negative. For example, people who belong to the category "one type of participation” are not predominantly voters.

12

“yes”/”no” answer to the question “Are you a member of an organization of association of

Romanians in (host country)?”.

7

The fourth independent variable, perceived discrimination, is measured as an ordinal index composed of three items of perceived discrimination: in the area of residence, on the street, and at the store. The question “During your stay in (host country) have you felt discriminated?” had the following answer options: “never”, “very little”, “little”, “much” and

“very much”. Each of these answers has been coded on a five-point ordinal scale and the new codes were cumulated to result in an index ranging from perceived discrimination in none of the contexts to very much perceived discrimination in all three situations. Media consumption, the fifth independent variable, is also an index of four items reflecting the frequency of access to newspapers, TV, radio, and Internet in the host country. The available answers were coded on a six-point ordinal scale (and then cumulated) that corresponds to

“never”, “once a month”, “two-three times a month”, “once a week”, “two-three times a week” and daily or almost daily”. With respect to the control variables, gender is a dummy (0

= female) and education is measured on a seven-point ordinal scale from primary school to graduate studies.

The empirical analysis consists of correlations and regressions. The former are meant to identify the bivariate relationships between the explanatory variables and political participation. The ordered logistic regression is used (the dependent variable is a five-point measure, the reference category is no participation) to test the hypotheses detailed in the previous section. The five models – one for the general situation and one for each country – also include the control variables.

Findings

The two-step analysis begins with the bivariate correlations aiming to identify the direction and strength of relationships. The evidence presented in the first sub-section is used as initial indication for the support of hypotheses at general and country-level. The second subsection includes the regression models that reveal the explanatory power of each variable in a multivariate setting.

7 The survey has asked the migrants about the activities of the associations and organizations in which they are members. The vast majority of respondents have joined cultural associations or organizations aiming to provide information for better integration. Only a limited percentage of respondents (between 3% in France and 8% in

Italy) mentioned membership in organizations with political activities and goals.

13

The bivariate analysis

The correlation coefficients presented in Table 2 indicate the existence of empirical support for almost all the hypothesized relationships. Although it does not test for causality, the identification of factors associated with the political participation of Romanian immigrants is relevant as a first impression about the general picture. The table distinguishes between the general situation (i.e. the respondents from all four countries) and country-level associations. At general level, all relations go in the hypothesized direction, but their strength varies considerably. The strongest correlation (higher than 0.3) is between political participation and the belonging to an organization and length of stay. The social network and media consumption correlate positively with participation, but slightly weaker (above 0.2).

Among the control variables education correlates higher than gender with participation indicating that better educated immigrants get involved in more participation activities than the rest (0.21). At the same time, male respondents indicate a higher propensity towards participation when compared to the female immigrants (0.11).

Table 2: Correlations between the explanatory variables and political participations

Between political participation and: General

Length of stay

Social network

Organization membership

Perceived discrimination

Media consumption

Education

Gender

N

0.30***

0.27***

0.34***

0.06*

0.21***

0.21***

0.11***

813

France

0.24***

0.27***

0.29***

0.03

0.18***

0.29***

0.09

293

Germany

0.16**

Notes: The presented coefficients are rank correlations (Spearman).

The reported number of respondents is the lowest among the variables.

***significant at 0.01; **significant at 0.05; *significant at 0.1.

201

Italy Spain

0.40*** 0.28*** 0.12

0.25*** 0.20*** 0.25***

0.30*** 0.35*** 0.41***

0.01 0.09 0.05

0.17** 0.27*** 0.23***

0.23*** 0.23*** 0.28***

-0.04 0.18**

137 182

The weakest correlation is between perceived discrimination and participation: people who perceive personal discrimination do participate more than the others, but they do so at a marginal rate (the coefficient is 0.06). With the exception of perceived discrimination

(significant at the 0.1 level), the other coefficients are statistically significant at the 0.01 level. This measure should not be interpreted in the traditional way of results’ applicability to a broader population. The sample is not probabilistic and thus generalizations do not make much sense. Instead, it is reported to indicate that the association is not accidental.

14

The direction of relationships and support for hypotheses are valid also at country level, but several particular characteristics require further discussion. In France, membership organization and education correlate the highest with political participation, followed by social network, period of residence, and media consumption. Gender is only weakly associated with male respondents being more politically active, whereas the perception of discrimination appears to play no role in participation. Apart from the low values of the coefficients, the latter two correlations are the only ones that lack statistical significance. In

Germany the length of stay, membership in organizations and social network are the highest correlated factors with participation. Similar to the French case, the perception of discrimination appears to make no difference in terms of participation.

In Italy, the membership in organizations, length of stay and media consumption rank as the highest correlated with participation. At the other extreme, perceived discrimination is among the weakest correlated. However, the coefficient is the highest among the investigated countries (0.09). This result is not surprising in light of the tensions emerging over the last years between Italians and Romanians. Following several criminal acts (mostly petty crime, but also some murders) media and state authorities have repeatedly depicted

Romanian immigrants in a negative light. This reality can partially explain the relevance of media consumption – the highest among the scrutinized countries – in shaping Romanians’ political participation. Italy is the only country in which female respondents were more politically active than men; this happened only at a marginal rate (0.04). For the Romanian respondents living in Spain the belonging to a membership and better education are the factors that correlate the highest with participation. Among the hypothesized variables, an extensive social network and daily media consumption also have relatively high coefficients, both statistically significant at the 0.01 level. As a specific feature, gender appears to make the highest difference among the investigated countries with men getting involved more into politics compared to women. The length of stay and perception of discrimination are weakly associated with participation.

Following the bivariate analysis three partial conclusions can be drawn. First, there is empirical support for at least four out of five hypotheses. Despite small variations between countries, the relationships go in the expected direction and many are relatively strong. The perception of discrimination is an exception as it makes a difference only in the Italian case

(and this also drives the result in the general pool). Second, the belonging to an organization

15

and the length of stay are the highest correlated variables with participation at general level and in three out of four countries. Third, among the control variables education appears to be a better explanation for participation; gender is weaker correlated and has contradictory evidence in Italy.

The multivariate analysis

The dependent variable of this study is a five-point measure of political participation.

Consequently, the empirical analysis testing for causality is an ordered logistic regression, the reference category being no political participation. The regression models presented in

Table 3 provide consistent and strong support for the first three hypotheses both at general and country level. For hypothesis 1 the odds-ratios presented on the first column indicate that a high period of stay in the country of residence has a positive effect on political participation. When all the respondents are included in the model the odds of political participation is 1.57 higher given long period of stay compared to a short period. Within the countries the odds have small variations around this value with a minimum of 1.42 in France and a maximum of 2.10 for the Romanian immigrants in Italy. All effects are statistically significant at 0.01 with the exception of Spain (at 0.1).

Hypothesis 2 finds most empirical support in France and the general model where the odds to participate are 1.30, respectively 1.12 higher for the immigrants with an extensive social network compared to those with limited network. In fact, the French case is the driver behind the effect observable at general level. The social network variable has no effect on the political participation of web survey respondents in Germany, Italy and Spain.

This is partly surprising due to the relatively high correlation coefficients presented in Table

2. Consequently, when included in a multivariate model the social network predictor loses its explanatory power.

The third hypothesis finds the strongest empirical support with members in organizations participating in politics considerably more than those who did not join an association or organization. At general level the odds are four times higher (with similar strengths of effect in Germany and France), whereas in Italy and Spain the odds are 6.33 and

6.51. The percentage of people who joined organizations is approximately 20% at the general level, a bit less in France and Germany and close to 30% in Italy and Spain. These differences are not large enough to represent methodological explanations for the different

16

effects. One substantial explanation for the two countries may be that people who join associations or organizations have articulated goals and are more interested in political issues (much more than in France and Germany). Consequently, the difference between members and non-members increases. Although the correlation between membership and social network is not high, the inclusion of the former leads to limited explanatory power for the latter. The regression model ran without membership in organization (not reported) indicates that social network gains explanatory power when the membership variable is not included (an increase to 1.20 in Italy and 1.29, statistically significant at 0.05 in Spain).

Table 3: Ordered Logistic Regression Analysis

Variables General

Length of stay

Social network

1.57***

(0.11)

1.12**

France

1.42***

(0.16)

1.30***

Germany

1.69***

(0.24)

1.02

Italy

2.10**

(0.52)

1.03

Organization membership

Perceived discrimination

Media consumption

Education

(0.06)

4.00***

(0.74)

1.04*

(0.03)

1.06***

(0.02)

1.42***

(0.13)

4.21***

(1.50)

1.03

(0.05)

1.05*

(0.03)

(0.13)

3.96***

(1.74)

0.97

(0.05)

1.04

(0.03)

(0.13)

6.33***

(3.16)

1.05

(0.06)

1.09**

(0.04)

Gender

(0.07)

1.43***

(0.23)

(0.15)

1.51*

(0.36)

(0.17)

1.99**

(0.57)

(0.17)

0.70

(0.27)

Likelihood ratio chi 2

Pseudo R 2

N

255.43

0.11

788

84.97

0.11

285

69.43

0.14

194

45.98

0.13

137

Notes: The presented coefficients are odds ratios with standard errors in brackets.

***significant at 0.01; **significant at 0.05; *significant at 0.1.

Spain

1.47*

(0.33)

1.01

(0.11)

6.51***

(3.05)

1.05

(0.06)

1.11**

(0.05)

1.38**

(0.17)

3.08***

(1.03)

54.05

0.13

172

Hypothesis 4 finds very weak empirical support, being statistically significant only at general level. The difference in participation is only marginal (1.04) but whenever it occurs the immigrants who see themselves as heavily discriminated participate slightly more than the rest. In Germany, the situation is reversed – when differences occur those who feel discriminated against participate less. In light of the bivariate analyses, the lack of effect is not striking. Hypothesis 5 also finds weak support in the hypothesized direction. The results indicate that those who often watch news have 1.04 (Germany) to 1.11 (Spain) higher odds of political participation compared to those who do not stay informed on a regular basis; he statistical significance varies greatly among the countries.

17

Education and gender have strong and statistically significant effect on political participation. The effects are in line with the positive correlations described in the previous section. A highly educated Romanian immigrant has up to 1.56 higher odds (in Germany) to participate compared to less educated immigrants, whereas a men participate more than women (e.g. three times more likely in Italy). Spain is the only country when women are more engaged in politics than men (the odds ratios is 0.70).

The visual presentation of some effects helps illustrating the existing differences.

Figure 2 displays the effects of length of stay on political participation (vertical axis) for each gender. As a result of the strong impact of gender on participation, the intercept is different

(i.e. participation starts at a higher level for men). However, the line with fitted values is steeper for women. This is an indicator of a higher difference in political participation between the immigrants with long and short period of residence compared to men.

Figure 2: The predicted effect of length of stay on participation for separate groups (gender)

Figure 3 plots the effect of education on participation, in line with the SES theories, for the group of members and non-members. The regression models have shown that membership in organizations has the strongest effect among all considered variables and this is also visible in the figure below. Apart from this difference, the effect of education is fairly similar in both categories – members and non-members.

18

Figure 3: The predicted effect of education on participation for separate groups (membership)

Conclusions

This paper aimed to identify the determinants of Romanian labor migrants’ political participation in four West European countries. It has theoretically argued in favor of the effect of five main effects related to individual orientations, attitudes, social interaction, and resources. The empirical results show that, despite small variations, the political participation is a function of fairly similar variables across countries. The membership in organizations, a longer period of stay in the country of residence, and the size of the social network explain best the engagement in politics of Romanian immigrants. To these features we can add education (the higher, the more active) and gender (men participate more than women).

These findings advance the general understanding of political engagement among immigrants. One important observation is that their behavior is driven by similar factors to those revealed in earlier research about non-migrants. The strong ties observed between civic (i.e. membership organization) and political engagement of Romanian immigrants are consistent with a large body of literature that emphasized their congruence at individual level. Similarly, the effect of length of stay in the country of residence is in line with the socialization theories that reveal the involvement that accompanies stability. It is also important to note that, similar to the case of non-migrants (Brady et al. 1995), the SES variables are not the only or strongest explanations for the participatory behavior.

19

Another relevant implication of these findings is that immigrants’ decision to engage in politics is influenced by characteristics acquired on the long-term (i.e. organization membership, social network, media consumption, education) as opposed to short-term issues such as the perception of personal discrimination. This means that political participation plays a complementary role to their efforts to be proactive (membership organization) or better understand what happens in their new societies (e.g. social network, media consumption).

Yet these results have pointed mainly to general patterns and identified several determinants. Further investigation will be needed to shed light on the causal mechanisms, i.e. under what conditions the political participation occurs. The appropriate type of investigations to fulfill this goal is qualitative and presupposes interviews with immigrants.

An alternative route for further research involves the survey of different types of migrants

(from various countries) with respect to their political attitudes and behaviors. Such an approach will allow observing not only the boundaries of participation in a broader context, but also to identify group-specific characteristics.

Acknowledgments:

The research for this paper has been conducted in the framework of the project PN-II-IDPCE-

2011-3-0394, funded by the National Council for Scientific Research in Romania. The author is grateful for constructive comments and useful suggestions on earlier versions of this paper to Andrea Blättler, Sebastian Fietkau, Francis Garon, Sara de Jong, Rahsaan Maxwell, and

Samuel Schmid.

20

List of references:

Almond, Gabriel A. and Sidney Verba (1963) The Civic Culture. Princeton: Princeton

University Press.

Arvizu, John R. and F. Chris Garcia (1996) "Latino Voting Participation: Explaining and

Differentiating Latino Voting Turnout”. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 18(2):

104-128.

Bahry, Donna and Brian D. Silver (1990) "Soviet Citizen Participation on the Eve of

Democratization”. American Political Science Review 48(3): 820-847.

Barreto, Matt A. and Jose A. Munoz (2003) "Reexamining the ’Politics of In-Between’:

Political Participation Among Mexican Immigrants in the United States”. Hispanic

Journal of Behavioral Sciences 25(4): 427-447.

Bimber, Bruce A. (1999) "The Internet and Citizen Communication with Government: Does the Medium Matter?” Political Communication 16(3): 409-428.

Bimber, Bruce A. and Richard Davis (2003) Campaigning online: The Internet in U.S. elections.

New York: Oxford University Press.

Brady, Henry (1999) "Political Participation” in John P. Robinson, Philip R. Shaver, and

Lawrence S. Wrightsman (eds.) Measures of Political Attitudes. San Diego: Academic

Press.

Brady, Henry E., Sidney Verba and Kay Lehman Schlozman (1995) "Beyond SES: A Resource

Model of Political Participation”. American Political Science Review 89(2): 271-294.

Browning, Graeme (1996) Electronic Democracy: Using the Internet to Influence American

Politics. Wilton, CT: Pemberton Press.

Budge, Ian (1996) The New Challenge of Direct Democracy. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bueker, Catherine Simpson (2005) "Political Incorporation Among Immigrants from Ten

Areas of Origin: The Persistence of Source Country Effects”. International Migration

Review 39(1): 103-140.

Burns, Nancy, Kay L. Schlozman, and Sidney Verba (2001) The Private Roots of Public Action:

Gender, Equality, and Political Participation. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Cain, Bruce E., D. Roderick Kiewet and Carole J. Uhlaner (1991) "The Acquisition of

Partisanship by Latinos and Asian Americans”. American Journal of Political Science

35(2): 390-422.

Chen, Jie (2000) "Subjective Motivations for Mass Political Participation in Urban China”.

Social Science Quarterly 81(2): 645-662.

Conway, Margaret M. (1991) Political Participation in the United States. Washington D.C.: CQ

Press.

Dalton, Russell J. (1988) Citizen Politics in Western Democracies. Chatham: Chatham House.

Dalton, Russell J. (2008) Citizen Politics. Public Opinion and Political Parties in Advanced

Industrial Democracies, 5 th edition, Washington D.C.: CQ Press.

De Rooij, Eline A. (2012) "Patterns of Immigrant Political Participation: Explaining Differences in Types of Political Participation between Immigrants and the Majority Population in

Western Europe”. European Sociological Review 28(4): 455-481.

Drew, Dan and David H. Weaver (1998) "Voter learning in the 1996 presidential election: Did the media matter?" Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 75: 292-301

Finifter, Ada W. and Bernard M. Finifter (1989) "Party Identification and Political Adaptation of American Migrants in Australia”. Journal of Politics 51(3): 599-630.

Fishkin, James S., Robert C. Luskin and Roger Jowell (2000) ”Deliberative Polling and Public

Consultation”, Parliamentary Affairs 53(4): 657-666.

21

Garcia-Bedolla, Lisa (2000) ”They and We: Identity, Gender, and Politics among Latino Youth in Los Angeles”. Social Science Quarterly 81(1): 106-121.

Gerber, Alan S., Gregory A. Huber, David Doherty, Conor M. Dowling, Connor Raso, and

Shang E. Ha (2011) “Personality traits and participation in political processes”. Journal

of Politics 73 (3): 692-706.

Hirschman, Charles, Philip Kasinitz and Josh DeWind (eds.) (1999) The Handbook of

International Migration. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Huckfeldt, Robert (2001) "The Social Communication of Political Expertise". American Journal

of Political Science 45 (2): 425-439.

Huckfeldt, Robert and John Sprague (1995) Citizens, Politics, and Social Communication. New

York: Cambridge University Press.

Inglehart, Ronald and Pippa Norris (2003) Gender Equality and Cultural Change around the

World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Inglehart, Ronald and Gabriela Catterberg (2002) "Trends in Political Action: The

Developmental Trend and the Post-Honeymoon Decline”. International Journal of

Comparative Sociology 43(3-5): 300-316.

Jennings, Kent. M. (1983) "Gender Roles and Inequalities in Political Participation: Results from an Eight-Nation Study". Western Political Quarterly 36(3): 364-385.

Jones-Correa, Michael A. (1998) Between Two Nations: The Political Predicament of Latinos

in New York City. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Kitschelt, Herbert and Philipp Rehm (2008) "Political Participation” in Daniele Caramani (ed.)

Comparative Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 445-472.

Leal, David L. (2002) "Political Participation by Latino Non-Citizens in the United States”.

British Journal of Political Science 32(2): 353-370.

Leighley, Jan (1995) “Attitudes, Opportunities and Incentives: A field Essay on Political

Participation”. Political Research Quarterly 48(1): 181-198.

Leighley, Jan (1996) "Group Membership and the Mobilization of Political Participation”.

Journal of Politics 58(2): 447-463.

Leighley, Jan E. and Vedlitz, Arnold (1999) "Race, Ethnicity and Political Participation:

Competing Models and Contrasting Explanations‟. Journal of Politics 61(4): 1092-

1114.

Lijphart, Arend (1999) Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-

Six Countries. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Manion, Melanie (1996) "The Electoral Connection in the Chinese Countryside”. American

Political Science Review 90(4): 736-748.

McAllister, Ian and Toni Makkai (1993) "Institutions, Society or Protest? Explaining Invalid

Votes in Australian Elections". Electoral Studies 12(1): 23-40.

McClurg, Scott D. (2003) "Social Networks and Political Participation: The Role of Social

Interaction in Explaining Political Participation”. Political Research Quarterly 56(4):

449-464.

McLeod, Jack M., Dietram A. Scheufele and Patricia Moy (1999) "Community, communication, and participation: The role of mass media and interpersonal discussion in local political participation". Political Communication 16(3): 315-336.

Milbrath, Lester W. (1965) Political Participation: How and Why Do People Get Involved in

Politics? Chicago: Rand McNally College Publishing Company.

Milbrath, Lester W. and Madan L. Goel (1977) Political Participation: How and Why Do

People Get Involved in Politics? New York: University Press of America.

22

Mishler, William and Harold D. Clarke (1995) "Political Participation in Canada” in Michael S.

Whittington and Glen Williams (eds) Canadian Politics in the 1990s, Toronto: Nelson.

Mutz, Diana C. (2002) "The Consequences of Cross-Cutting Net- works for Political

Participation". American Journal of Political Science 4(4): 838-855.

Nie, Norman H., Jane Junn, and Kenneth Stehlik-Barry (1996) Education and Democratic

Citizenship in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Parry, Geraint, George Moyser and Neil Day (1992) Political Participation and Democracy in

Britain. London: Cambridge University Press.

Pateman, Carole (1970) Participation and Democratic Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Peterson, Steven A. (1990) Political Behaviour: Patterns in Everyday Life. London: Sage.

Putnam, Robert (2000) Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New

York: Simon & Schuster.

Putnam, Robert D. (with Robert Leonardi and Raffaella Y. Nanetti) (1993) Making Democracy

Work. Princeton: Princeton Universitiy Press.

Richardson, J (ed.) (1993) Pressure Groups. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rosenstone, Steven J. and John Mark Hansen (1993) Mobilization, Participation and

Democracy in America. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company.

Ruedin, Didier (2011) "The Role of Social Capital in the Political Participation of Immigrants

Evidence from Agent-Based Modelling", Swiss Forum for MIgration and Population

Studies, Discussion Paper SFM 27.

Scheufele, Dietram A. (2002) "Examining differential gains from mass media and their implications for participatory behavior". Communication Research 29(1): 46-65.

Schildkraut, Deborah J. (2005) "The Rise and Fall of Political Engagement among Latinos: The

Role of Identity and Perceptions of Discrimination”. Political Behavior 27(3): 285-312.

Schlozman, Kay Lehman, Nancy Bums, and Sidney Verba (1993) "Gender and the Pathways to Participation: The Role of Resources” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, Chicago.

Schulz, Donald E. and Jan S. Adams (eds.) (1981) Political Participation in Communist

Systems. Oxford: Pergamonn Press.

Shah, Dhavan V., Jaeho Cho, William P. Eveland Jr. and Nojin Kwak (2005) "Information and expression in a digital age: Modeling Internet effects on civic participation”.

Communication Research 32(5): 531-565.

Tam Cho, Wendy K. (1999) "Naturalization, Socialization, Participation: Immigrants and

(Non-) Voting”. Journal of Politics 61 (4): 1140-1155.

Teorell, Jan (2003) “Linking Social Capital to Political Participation: Voluntary Associations and Network of Recruitment in Sweden“. Scandinavian Political Studies 26(1): 49-66.

Teorell, Jan, Mariano Torcal and Jose Ramon Montero (2007) "Political participation:

Mapping the terrain” in Jan van Deth, Jose Ramon Montero and Anders Westholm

(eds.) Citizenship and Involvement in European Democracies. A Comparative Analysis.

London: Routledge, 334-357.

Urwin, Derek W. and William E. Patterson (eds.) (1990) Politics in Western Europe Today:

Perspectives, Policies and Problems since 1980. London: Longman.

Van Deth, Jan (ed.) (1997) Private Groups and Private Life: Social Participation, Voluntary

Associations and Political Involvement in Representative Democracies. London:

Routledge.

23

Verba, Sidney (1978) Participation and Political Equality: A Seven Nation Comparison.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Verba, Sidney (2003) "Would the Dream of Political Quality Turn to Be a Nightmare?”

Perspectives on Politics 1(4): 663-679.

Verba, Sidney, and Norman H. Nie (1972) Participation in America: Political Democracy and

Social Equality. New York: Harper & Row.

Verba, Sidney, Kay L. Schlozman, and Henry Brady (1995) Voice and Equality: Civic

Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Verba, Sidney, Kay Lehman Schlozman, Henry Brady, and Norman H. Nie (1993) "Who

Participates? What do They Say?". American Political Science Review 87(2): 303-318.

Verba, Sidney, Norman H. Nie, and Jae-On Kim (1978) Participation and Political Equality: A

Seven-Nation Comparison. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Web Survey Report, http://fspac.ubbcluj.ro/ethnicmobilization/wpcontent/uploads/2011/12/Research-report-Romanian-migrants-websurvey1.pdf.

24