Gender Differences in Religious Practice and

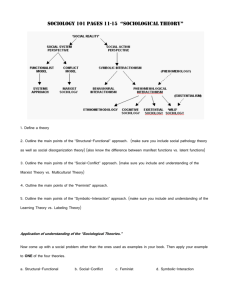

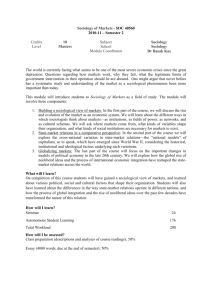

advertisement