"Cirtuous Citizenship": Ethnicity and

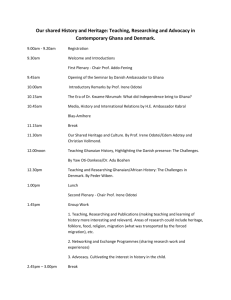

advertisement

“Virtuous Citizenship”: Ethnicity and Encapsulation among AkanSpeaking Ghanaian Methodists in London Mattia Fumanti Paper for the Conference on African Transnational and Return Migration in the Context of North-South Relations, University of Warwick, Coventry, United Kingdom, 29-30 June 2009 1 Abstract: This paper examines the ways first generation Ghanaian Methodists in London construct citizenship in the context of highly encapsulated ethnic fellowships, characterised by the exclusive usage of Akan, Ghanaian styles of worship and an ethos of mutual assistance. Encapsulation seems irreconcilable with an idea of an active citizenship as grounded in participation in the public sphere of the nation. Yet it is within these encapsulated fellowships that first generation Ghanaian Methodists construct citizenship through the making of a diasporic Ghanaian identity grounded in the ideas of hard-work, respect for the rule of law, virtue and morality. Building on Aristotle’s concept of citizenship as an expression of virtue, goodness and the preservation of harmony among citizens and the state, I call Ghanaian Londoners, often ‘virtual’ in the sense of lacking legal residence, ‘virtuous citizenship’. The paper also addresses issues of multiculturalism and tranansnational belonging through an analysis of a current debate within the Methodist polity. Keywords: Citizenship, Ethnicity, Methodism, Ghanaian diaspora, London, Multiculturalism Introduction The literature on the new African Diaspora in Britain and the US has tended to underline loss of status, alienation and invisibility experienced by African migrants. Stoller (2002), for example, citing Ellison’s Invisible man, describes the experience of a Songhay trader in New York as the life of ‘an unseen person... who walked among the shadows’ (2002:6), while Akyempong (2001) and Vasta and Kandilige (2007) argue that Ghanaians conceptualise London as ‘the great leveller’. Arriving from Africa often with high-level professional qualifications and education, Ghanaian migrants end up in menial jobs and experience a loss of status: ‘the elites rubbing shoulders with the illiterates’ (Akyempong 2001: 196). JoAnn McGregor describes the experience of shame associated with de-skilling among Zimbabwean 2 professionals working in care homes for the elderly (McGregor 2007). In this context, nostalgia for home, and the pain of disconnection take centre stage in powerful narratives of displacement (D’Alisera 2004). This is also expressed in novels such as The children of the revolution on Ethiopians in Washington D.C (Mengestu 2007). Such an emphasis on alienation and loss of status, while capturing a deep-seated truth on the reality of racism and daily discrimination encountered by many African migrants, can potentially, overlook the complexity of the new African diaspora experience. Alienation and invisibility may disguise active citizenship within a diaspora community, invisible to outside bodies, although undoubtedly, incoming migrants do find some aspects and values of the society they live in deeply unsettling (Stoller 2002, d’Alisera 2004). Against this alienation and invisibility, social involvement with their communities opens up for migrants other avenues for recognition and distinction. Encapsulation in political, religious and mutual aid associations has long been recognised as an essential aspect of the process of settlement in a new country (Mayer 1971, Whyte 1943, Werbner 1990, 2002)1. As Sam Selvon’s (1956) classic novel, The Lonely Londoners, on post-war migration from the Caribbean reminded us more than fifty years ago, hopes and dreams, places of recognition and visibility, co-exist with alienation and invisibility. This paper aims to build on this dualism in the literature by addressing the way in which Ghanaians in Britain negotiate their sense of belonging and citizenship while remaining double rooted, commited to both Britain and Ghana, and despite being in some cases overstayers who are neither British citizens nor legally resident in Britain. In particular, the paper reflects on the way that membership in the Methodist church in Britain and Ghana mediates for Ghanaian Methodists a sense of citizenship, based on moral and ethical ideas of virtuous performance. 1 For a discussion on the new African diaspora see Grillo and Mazzucato 2008, Krause 2008, Fumanti 2009, Mazzucato 2008, Mohan 2006, McGregor 2008, Page, Mercer and Evans 2009. 3 For first generation Ghanaian Methodist migrants in London the Methodist church becomes a space for the construction of a unique ‘diasporic' citizenship, irrespective of the formalities of passports and voting rights. This is because the church constitutes for migrants a transnational polity, one that is both British and Ghanaian, a naturalised, taken-for-granted continuum arising from the long history of Methodism as a British mission in Ghana (Bartels 1965). For Ghanaians in Britain, whether or not they are officially full British citizens outside the church assumes secondary importance to their sense of entitlement as postcolonial citizens returning to the home country. Critical is their status and role within the church itself. Though in many cases lacking official papers, and frequently suffering discrimination and loss of status at work, with many employed in manual labour despite their educational qualifications, the Methodist church provides the space where Ghanaian migrants can construct their sense of being both ‘British’ and worthy citizens. This stems from migrants’ recognition of the Methodist church as an essentially British institution which recognises their loyalty and allegiance whatever their formal status. By working and achieving recognition within the church, they see themselves as living virtuous and dignified lives in British society more generally. The church is thus a space where their contribution to Britain as good Christians within a Christian nation is morally acknowledged. Ghanaian Methodists construct their subjecthood as virtuous performance. According to this ideal, citizenship, the right to national belonging, is achieved by being law abiding, hard working, and actively involved in Methodist fellowships through acts of caring, charity, nurture, and human fellowship. Nevertheless, the space of the church is also the space in which tensions inherent in the wider concept of citizenship between universalism and particularism are played out. On the one hand, citizenship for Ghanaians is founded on universal Christian values of love and care. They phrase this in terms of the Akan concept of empathy, ɔtema. On the other hand, universal caring remains in tension with particular 4 membership in Ghanaian ‘ethnic’ fellowships. These often exclude Caribbeans and other African groups within and outside the church. Moreover, their highly moralistic ideal of proper conduct promotes a sense of moral superiority in relation to the ‘English’, the host society, and a negative judgement of their perceived immoral and sinful behaviour. Hence, competition and opposition both within and beyond the ethnic group typifies membership in Akan Methodist fellowships. Indeed, my paper discloses, the Akan tendency towards encapsulation and ethnic particularism within the church has come to be regarded as highly problematic by the church hierarchy, and has led to calls for an internal debate and reflection on the role of ethnic minorities within the Methodist polity. This marked tendency towards local and transnational encapsulation among Akan speakers has implications for the wider debate on multiculturalism in Britain. In effect, their ethnically exclusive fellowships lead to the creation of a bi-polar transnational social field within the confined space of a single institution, the Methodist church, which itself is both British and transnational. This feature of the church allows for the simultaneous negotiation of different citizenships. On the one hand, being members of a transnational polity whose roots and centre are in Britain makes Ghanaians in their own eyes naturally British citizens, but it also permits them to create ethnic fellowships which transcend the boundaries of the nation, while at the same time transforming the church into a multicultural polity. For more recent Ghanaian migrant arrivals, living in London without residence visas or work permits, the presence of Ghanaian Methodist fellowships signifies a British recognition of the contribution made by Ghanaians to the UK as British citizens and helps legitimise their presence in Britain in their own eyes since, despite their illegal status, they are citizens within the British Methodist Church. For those who have been settled in the country over a longer period of time and possess all the necessary legal documents, the Ghanaian Methodist fellowships become a space to celebrate diversity, by maintaintaining 5 their unique cultural link with their home country and remaining engaged in the project of Ghanaian nation-building while living in the diaspora (Mercer, Page & Evans 2009). Both these groups come together within the framework of the church. Within multicultural Britain, the church constitutes an ideal space for intercultural dialogue. As a British religious institution with a long history of engagement in social justice and progressive themes, British Methodism has undergone considerable transformation in recent years in order to accommodate a growing number of ethnic fellowships. The ensuing debate created by the efflorescence of such ethnic fellowships mirrors wider debates on citizenship and multiculturalism in Britain. As in Britain as a whole, themes of allegiance to the British Methodist church, of active citizenship, of cohesion and integration, are central to this internal debate in the church, especially as it relates to the more highly encapsulated ethnic fellowships like the Ghanaian ones. Addressing active citizenship in Britain: towards a Feminist and Aristotelian synthesis These new challenges can be met only by government and people working together, met only by an active citizenship, only by involving and engaging the British people and forging a shared British national purpose that can unify us all... Here is the deal for the next decade we must offer: no matter your class, colour or creed, the equal opportunity to use your talents. In return we expect and demand responsibility: an acceptance that there are common standards of citizenship and common rules. And this is the British way: to say to all who live in our country there are common standards and rules to be upheld. (Gordon Brown, Labour Party Conference 2007) Over the last decade Britain has seen the affirmation and consolidation of a more communitarian definition of citizenship. Based largely on the American republican model in its late 20th century version (see for example Etzioni1993, Putnam 2000), the communitarian 6 tradition places great emphasis on active citizenship and, as Gordon Brown underlined in his speech, on shared rights, obligations and common standards for citizens. This is seen largely as opposing an individualist, liberal tradition. It aims to promote the sense of collective duties and social rights over individualism, technical expertise and the alienating tendencies of market capitalism. As T.H. Marshall famously emphasised (1964), individual definitions of citizenship, although potentially emancipating, cannot eradicate class and inequality. Instead, he defined citizenship as ‘a status bestowed on those who are full members of a community’ (1964: 84). Although Marshall’s view was progressive, laying the philosophical foundations for the welfare state, a number of feminist scholars have pointed out that the communitarian stress on belonging and ‘actively joining with others to promote the common good in a community’ (Assiter 1999, 44), is exclusionary in the sense that it tends ‘to homogenise groupings’ and ‘to gloss over class, gender, racial and other power differentials between groupings, in the interest of generating a common identity and a common value system’ (Assiter 1999: 45). Against the homogenising vision of the communitarian tradition and the alienating approach of the liberal tradition, feminist critics have suggested alternative constructions of citizenship. Lister (1997), for example, proposes a feminist synthesis of the liberal and communitarian traditions that would address citizenship’s exclusionary power and the publicprivate dichotomy (see also Prokhovnik 1994). Lister argues that contrary to the stress on universalism, citizenship has long excluded women and other groups, such as ethnic minorities and the disabled, ‘from the theory and practice of citizenship’ (Lister 1997, 38), relegating women to the private sphere. As a corrective to this false universalism, Lister proposes the notion of a ‘differentiated universalism’ - ‘a universalism which stands in creative tension to diversity and difference and which challenges the divisions and exclusionary inequalities which can stem from diversity’ (Lister 1997: 39). Writing about the 7 disability movement, Judith Monks suggests that it advocates an ‘alternative form of citizenship which provides for a flexible kind of participation’ based on intersubjectivity and relationality (Monks 1999: 66). Assiter suggests that citizenship should ‘not take it for granted that individuals are members of nation-states’ (1999: 41), while Stasiulis and Bakan argue that citizenship ‘is negotiated and is therefore unstable, constructed and re-constructed historically across as well as within geo-political borders’ (1994: 119; see also Werbner and Yuval-Davis 1999). These theoretical alternatives to legalistic definitions of citizenship are seminal, allowing for a novel conceptualisation that aims to take into account intersubjective moral relations between citizens. Assiter uses the notion of an epistemic community, drawing on Aristotle, to refer to ’a group of individuals who share certain interests, values and beliefs in common... and who work on the epistemic consequences of those presuppositions’ (Assiter 1999: 47). A key aspect in Aristotle’s theory overlooked by Assiter, however, is his invocation of virtue, ἀρετή, to describe the good citizen, καλὸς κἀγαθόs, as the ideal (Adkins 1963, Newell 1987, Develin 1973). For Aristotle, citizenship is negotiated through the intersubjective communication and pragmatic responsiveness to circumstances (Aristotle 1950, Adkins 1963, Develin 1973). In this latter respect, citizenship is always specific; limited to a particular community and particular historical setting, and the right to be a participatory citizen is dictated by individual status. For Aristotle the virtuous citizen, the ἀγαθός, remains an ideal, achievable only by those able to combine the universal qualities of humanity proper, of the virtuous man, with the particular qualities of being a citizen subject to the law of the πόλις. As he says in the Politics, ’Now in general a citizen is one who both shares in the government and also in turn submits to be governed’ (1950: 92). As Adkins (1963: 35) points out, the good man/citizen, καλὸς κἀγαθόs, relied for his survival and well-being on a clearly defined and demarcated community in which virtue, mutual assistance, cooperation and trust were debated and agreed 8 upon. This was more so for those living in a foreign land (1963: 35). There, survival was often reliant on the patronage of good men within the household or οἶκος. It was in this highly encapsulated space that the individual made sense of his experience and was taken care of, nurtured, protected and recognised. If we extend this notion of οἶκος to the migrant community, we may argue that encapsulation within the church provides the protective environment needed to survive in a foreign land. In Aristotelian terms, a flexible, postcolonial diasporic citizenship is expressed by the notion of virtuous citizenship within the British Methodist church. The church provides a ‘nurturing’ space where Ghanaians organise themselves in encapsulated fellowships, coming together to worship and celebrate their contribution to Britain and Ghana through their efforts in the church. In the process they construct an ideal model of virtuous citizenship, one that encompasses their experience as subjects and citizens in Britain and in Ghana. Within the fellowships differences in immigration status and time are erased. There is space for both newcomers and pioneers, the long-term settlers, to cooperate, engage, and negotiate their presence in Britain. Encapsulation within the fellowship thus allows even newcomers to achieve status, regardless of legal formalities. In the context of the Methodist church these are rendered meaningless, conflated with the ‘British’ qualities of being virtuous, hard-working and law-abiding. Ghanaian Methodists in London thus understand their role as citizens not through their direct active engagement in the national British public sphere, but through their active participation in the Methodist church, its fellowships and associations, the help they extend to their families in Ghana and Ghanaian nation-building. Being virtuous in their conduct towards their fellow Ghanaians in Britain and at home qua subjects-citizens, they also perform a moral role in bringing back the word of God to Britain. They work hard, pay taxes, attend to the need of others, donate generously to the church and for other causes, help 9 organise and attend public events and traditional rites of passage such as weddings, naming ceremonies and funerals, and take part in welfare initiatives within the church and other national and ethnic associations. This ideal of the virtuous postcolonial citizen is informed both by Protestant Christian ethics, in particular the Methodist concept of holiness, the pursuit of individual Christian perfection, and by Ghanaian cultural values, specifically the Akan concept of ɔtema a relational and dialogical concept meaning empathy and compassion, which contains the idea of the pain people feel when pain is inflicted onto others or people are thought to be suffering. To have ɔtema means to possess the emotional and human capacity for sociality, to feel and attend to the need of others. This concept, shared by several ethnic groups in Ghana, defines Akan’s inter-subjectivity. For Akan in London it is cited to explain why Ghanaians are law-abiding and caring, and are apparently not involved in criminal activities. Yet like the Aristotelian and Greek concept of καλὸς κἀγαθόs (Donlan 1973), there are tensions between the universalist Christian message of holiness and the Akan concept of ɔtema on the one hand, and the particularism practised by encapsulated Ghanaian Christian fellowships, on the other. These exclude non-Ghanaians, while also revealing great deal of competition among the different Christian fellowships. Like for the Greek καλὸς κἀγαθόs, the Ghanaian virtuous citizen is pulled between personal interests and civic excellence (Develin 1973:71) To be an ideal citizen is hard, achievable by a few celebrated individuals, but the concept nonetheless help making sense of their lived experience as African migrants in London, living in an often hostile environment, without recognition and distinction in the public sphere. Ghanaians Methodists in London and the Construction of virtuous Citizenship 10 The year 2007 was highly symbolic for Ghana, the fiftieth anniversary of Ghanaian Independence. In London this historical event was marked by a great number of celebrations, culminating in an official state visit of (now former) President John Kuffour. Nicknamed ‘the gentle giant’ for his caring and unassuming attitude despite his considerable height, the President embodied a new era in Ghana’s history, as the country has made great progress under his rule, politically, socially and economically. His visit to London caused great excitements for the UK Ghanaian diaspora, who perceives themselves as having contributed directly to Ghana’s financial growth and rising reputation, and are perceived as having raised the country’s international profile through their law-abiding,qualities, hard work, and Christian moraly .They are the ‘true ambassadors of Ghana’2 -- of the country’s moral, civic and religious values. This discourse is particularly central to the way in which Methodist Ghanaians have come to conceptualise their presence in Britain. Throughout 2007, the Ghanaian Methodist Fellowship in Britain was very active in the organisation of the Independence celebrations, hosting a number of events including two thanksgiving religious services at the Methodist Westminster Central Hall. Westminster Central Hall is a highly significant space for Methodists worldwide. A grandiose and imposing building in the centre of London, opposite Westminster and the House of Commons, it symbolises the desire of Methodism to emerge in the public sphere in Britain as a religious institution directly engaged with the political, moral, and social life of the country (Frost & Jordan 2006: 124). For Ghanaians in London, worshipping at the Westminster Central Hall, and indeed in other churches within London’s Methodist landscape, is a sign of their contribution to Britain and of their recognition as good Christians and good citizens. At the thanksgiving service held for President Kuffour at Westminster Central Hall, a Ghanaian Minister living in Britain led the prayers for the large congregation 2 These words were pronounced by His Excellency Annan Cato the Ghanaian High-Commissioner to Britain on the occasion of the Ghana at 50th dinner dance party held at the Ibis Hotel, London, in March 2007. 11 of Ghanaians, with the following words: “We are here, praying for the greatness of this country, Great Britain. This is a Christian country and the Queen, when she was enthroned, was given a Bible to lead this country. We know that many centuries ago people prayed for this country and they did it so well that the country is where we are now. Also, we praise Britain because it gave us John Wesley... and as he said, Praise the Lord!’” The Minister then opened the singing of a famous Methodist hymn backed by the congregation, singing with great passion, waving handkerchiefs, smiling and dancing. “We are jubilating,” a woman told me. The Minister continued: “Everyone in this country knows that we are hardworking people and law abiding. We have many people of success in the UK, Essien (the famous Chelsea footballer)” -- the congregation laughed -- “doctors, lawyers and policemen, etc. May God bless the work of our hands and our contribution to the United Kingdom! We pray the Lord to give us strength to help the Christian history of this country. We pray for their leadership, but we especially pray for its citizens. We are also part of it. God bless Great Britain!” In the Minister’s words Ghanaians have made a significant contribution to Britain. It is a contribution that symbolically links postcolonial Ghanaians with colonial Britain and Ghana through Christianity. For Ghanaian Methodists it is signalled in the words of the Minister through the figure of John Wesley, founder of Methodism (Halevy 1971). Indeed, John Wesley is appropriated as a Ghanaian; he has become part of the historical consciousness of Ghanaian Methodists, a shared ancestor transforming Ghanaian Methodists into British citizens. More tacitly the Minister’s message reiterates the strong link between state and church for nation-building and for the making of citizenship3. This is part of a public narrative in Ghana that associates the state with the church, and according to which religious institutions like Methodism are seen as the main actors in public political life of the 3 At the inaugural speech of the Annual Conference of the Presbyterian Church of Ghana the Vice-President Alhaji Aliu Mahama “called on the Church to partner the State to overcome challenges such as poverty, malnutrition, the digital attitude and unemployment” (www.ghana.gov.gh 20/08/2007) 12 postcolony4. If British people have prayed successfully for their own country and contributed to its growth, Ghanaians aim to do the same both for Britain and for Ghana. In leaving the building, my companion commented that ‘of course, if you do not have the passport you are not British, but we contribute to this country, as the Minister said, we pay taxes, we work, and especially in the church we do a lot... there you can say we are [citizens]’. John is a first-generation Ghanaian migrant who, like other Ghanaians and Africans in London, has overstayed his working visa. He knows he is not fully a British citizen; he can only consider himself a law-abiding, hard-working subject, but he also wants to share in the minister’s message of Ghanaians’ contribution to the UK. He is ready to recognise his own contribution to Britain by sharing vicariously the achievements of those who have made it -- the lawyers, doctors and policemen, even the footballers. He also shares in the common history binding the two countries via Methodism and their moral role as Christians. It is in the work in the church, John stressed, that Ghanaians in London become active citizens and hence entitled to be regarded as British citizens. By stressing ‘Godfearing’ as a Ghanaian quality he reiterated a widely shared discourse that regards religious belief as the prerequisite for a virtuous life in the community. Citizenship therefore is not bound to formal status, but is linked to agency and participation. Empathy (ɔtema), Christian Ideology and the virtuous citizen Ghanaians fear being tarnished with “shame” (animguase) if the honour of the wider community is compromised by their behaviour. Although they say that they are just in Britain to work and help their families and Ghana with their remittances, they also see themselves as contributing to the economy of Britain. For those who have no legal status and rights and 4 A recent example of the influential role of Christian religious institutions in Ghana is the reinstatement by the Ghanaian government of “compulsory Religious education” in Ghanaian schools after a high-profile public campaign lead by a number of Christian churches that demanded that the government overturn a previous decision. Ghana’s President orders schools to reintroduce religious and moral education, in (www.assistnews.net, 10/04/2008) 13 who cannot vote or participate fully to the public and political life of Britain, being an active citizen is difficult. Yet people are adamant that they contribute to Britain and they see their presence here as a positive presence, especially in moral terms. Kofi, a member of the Ghanain Methodist Fellowship, puts this clearly: Ghanaians migrants, both legal and illegal, are in fact the best people to work with. They are the best citizens but they are not recognised. They are the best citizens because they are not troublesome, they work hard, they are quiet. They wake up, go to work, shop, go home, cook and then go to work again. They mingle with the Ghanaian society and then are also God-fearing. (interview, London, May 2007) Moreover, they are bringing back the word of God to Britain. They are the new Christian missionaries who, like their European counterparts in colonial Africa, are bringing Christian values to the largely immoral British society (Ter Haar 1998, Van Dijk 1997). They are teaching by example the respect for the word of God, for elders, the value of marriage, of family and community. The presence of Ghanaians in many different churches and the growth of Ghanaian Independent churches seem sufficient to prove their moral contribution to the British way of life, despite their relative encapsulation. Their advance within the church structures is proof of their contribution. Ghanaians worship regularly at the Westminster Central Hall, boast the largest congregations in most London Methodist churches, and were the first to be recognised as an ethnic fellowship by the British Methodist Church when it granted them their own chaplaincy. Ghanaians are adamant that they are making way into the ‘heart of Britain’5 through their religious congregations. This sense of moral worth is captured in their hymns, sung in Twi6, part of the Methodist liturgy. The hymns carry religious messages of moral worth inscribed in the singers’ regimented 5 Informal conversation with Ama, London, April 2007 These hymns are the direct translation in Akan of the traditional Methodist hymns. See Hymns and Psalms, Methodist Publishing House. 6 14 postures,7 but Ghanaians are adamant that their contribution goes further, and is contained in their dances and drumming. Their liturgy, in their view, is richer and more colourful than the English version, and it has brought strength to an otherwise ‘boring’ church. This sense of recognition and moral worth is nurtured within the Christian fellowships. The fellowships are seen as the space for care, nurture, and attendance to the need of others. Branches of Ghanaian fellowships at home, they form a single umbrella organization much like their Ghanaian counterparts. For Ghanaians the fellowships acts like the abusua, the matrilineal clans, and like the abusua, the fellowships take care of their members on any occasion, most especially in the course of funerals, ayiyε, which are central to the formation of Akan personhood. As one minister remembered in the course of a sermon: On the Cross Jesus wasn’t thinking about himself but of us. This is what you are expected to do. Think of the other first and then yourself. A lot of people don’t know the meaning of the word fellowship. Fellowship is unity. It is coming together and helping each other. If it doesn’t happen is not a proper fellowship. When you send money back home you do it for the people you love. They are the ones you think of. If something happens we all contribute. We help the person and this means love. The fellowship is like a family. (Reverend A.O, London, January 2007). Like in a family, the fellowships encourage nurturing and helping others in need, both materially and spiritually, and they are the space in which Ghanaians reflect on their condition as migrants. Using the famous story of Jesus returning to Nazareth in Luke’s gospel the Minister brought home this point: It is very interesting when we go for a visit to Ghana, something funny happens. You go home and then everybody wants to see you. Your father and mother take[s] you out to see everybody, the son has come from overseas. They are very happy. They 7 For a comparable analysis see Mbembe 2007 15 want to see you and your parents boast about you.Everyone wants something from you. But people shouldn’t expect that, because true love is beyond materialistic things. (Reverend K.A, London, February 2007) In the course of church meetings members pray for other members, for congregants’ families in Ghana, and for the local church. But they also pray for wider communities. They direct their prayers to the Methodist church, to Britain and to people who are suffering worldwide. These prayers move from the particular concerns of individuals for the well-being and success of immediate relatives, to the universalist values of a Christian in the world ecumene. They often pray for God’s intercession in relation to matters or events that ‘have touched their hearts’. Reflecting on local and world news, they prayed, for example, in the course of my research, for the victims of the Virginia high-tech shootings, for the victims of the earthquake in Pakistan, for Madeline McCann’s safe return and for the release of Korean Christian missionaries in Afghanistan. At times these prayers are encouraged through chain text messages: ‘This is a prayer chain 4 Madeline who was kidnapped on holiday in Portugal, please pray for a quick safe return 2 her parents and fwd this to evry1 on your contact list. Never underestimate the power of prayer. You got to send this on. God Bless.’ Fellowships enable people to nurture universal Christian values of care and compassion alongside the Akan idea of empathy, ɔtema: “You see, we Ghanaians have this thing... it is taught to us since you are a child...and people are reminded of it when they do something wrong... don’t you have any of it?”8 Ɔtema was not prominent in people’s everyday conversations. It was taken for granted that adults possess it, but it emerged clearly as a public discourse at funerals. During bereavement, fellowships show their generosity through generous donations and material and spiritual support. And it is in bereavement that people are able to show ɔtema. One friend told me: ’We organise funerals for our members... 8 Informal conversation Ama, London, October 2007 16 as you know we Ghanaians like funerals... we help them, we support them... so ɔtema is this capacity to feel the pain... to feel the pain that the other person is feeling. Without that you would not be able to help the person... you need to feel it.’9 She stressed her point by clenching her fist and touching her heart. Empathising, feeling the pain that other people feel, are central to the universalist value of humanity. ɔtema empathy, as the basis for humanity, thus overlaps with Christian concepts of compassion, care and love. These are intersubjective notions that help Ghanaian Methodists, and more generally Ghanaians, to elevate their lives in London to a higher moral plane, which encompasses both diaspora Ghanaians and nonGhanaians alike. It is this capacity to empathise, to have ɔtema that potentially makes Ghanaian migrants virtuous citizens in the church and in Britain: ... it is not that Ghanaians do not commit crime and steal in this country... you know some of them they do, of course... but I think that Ghanaians do not really commit crimes because they know their limits... they like making money easily, like everybody, but you have this thing, ɔtema, they are thought about since they are kids... it is the feeling of the pain you cause unto others... so that is why they stop...” (Ekuia, London, November 2008) Nevertheless, the high levels of Ghanaian encapsulation within their fellowships have been criticised as exclusionary by other church members and the church hierarchy, concerned about schismatic tendencies. This is exemplified by the case of a recent Ghanaian migrant overstayer who has emerged as a well known figure in London Methodist Diaspora. His biography illustrates the tension between the concepts of the virtuous active church citizen and subject of multicultural Britain. The virtuous and virtual life of an overstayer 9 Informal conversation, 17 John is a first generation Ghanaian Methodist from the Ashanti region in Ghana. A member of a middle-class family of educationalists and prominent members within the Methodist church in Kumasi, he arrived in London in 2003, leaving behind his wife and children. A certified accountant in Ghana, and formerly the manager of an import-export company in Accra, John works in London as a builder and cleaner on the London Underground. Like many other middle class Africans who arrived in London with qualifications, from a relatively wealthy background, John has experienced a loss of status (McGregor 2007, Akyempong 2001). He doesn’t particularly like his jobs, seeing them as too menial, and feels that his true potential is unrecognised in Britain. However, not having permanent residence leaves him with no alternative. Like many other first generation Ghanaian migrants, his social life in London is highly encapsulated. His network of contacts revolves around his extended family, former school friends and church and associations members. These contacts have helped his settlement in London in one way or another. An uncle wrote the letter inviting him to Britain, and he first arrived with a working visa; another uncle hosted him for six months before he was able to find his own accommodation; a former business associate in Accra helped him find his present jobs; a cousin helped him with the bureaucratic procedures of obtaining a National Insurance Number and GP registration; a friend gave him his first TV and a mobile phone. All these relations have remained part of John’s network of mutual dependence and indebtedness that link him simultaneously to London and Ghana. It is, however, to the Methodist church that he told me he felt the most indebted. The church provided him with the space to acquire the recognition and status he had lost when he came to Britain, and made it possible for him to conceive of his presence in the country as an active and virtuous citizen and a law-abiding subject, despite the lack of formal papers. John called himself a ‘staunch Methodist’ and said he would not want to change his affilitation for anything else. He saw Methodism as a very positive force in his life and in the 18 life of his country, Ghana. Methodism was associated for him with nation building, and especially so in the field of education in which Methodist schools have achieved excellence. As I was told by one church minister: [t]he best schools in Ghana are religious schools and the best among them are the Methodist schools... If you look at the history of Ghana, at independence the cabinet ministers were for the majority graduates of Mfantsipim College. This is a Methodist school and the first secondary school in Ghana. In fact, we can say that Ghana was born in Methodism. (interview, K.A. November 2006). One acquaintance even suggested to me that the Methodist church could act as the government in Ghana ’since the church’s constitution is like the country’s constitution.’ John, alongside other Ghanaian Methodists in London, aimed to extend the positive force Methodism has had on the material growth of Ghana to Britain. He phrased this in moral terms: Ghanaian migrants would bring spiritual growth to the British Methodist church and by extension, to the whole of Britain. He took great pride in what he saw as the consolidation and recognition in Britain achieved by Ghanaians. Commenting on the number of British ministers who have recently travelled to Ghana, he told me: ‘You see, these ministers, they like going to Ghana, they want to see and learn and bring our style of worship here... they know that they can’t do things without us anymore.’ (May 2007). For John the British Methodist church was seen as dependent on Ghanaian church members. This echoed a broader argument on the contribution made by migrants to the British economy. Just as industries such as the service sector, health and caring were dependent on migrant labour, so too churches also needed the presence of migrants for their survival, growth and consolidation. But because Methodism is British, Ghanaian Methodists see their contribution to Britain as more important than that of other churches. John stressed this point: 19 It is like with many things in this country. This is the country of Methodism. They brought Methodism to us in Ghana and now they are forgetting it. We are here to help them rediscover that. It is like we are bringing it back to help here; to help with the spiritual life of the country. John took an active role in the Ghanaian Methodist Christian fellowships. He attended church regularly at a Methodist church in North London where he was a steward, as well as being the financial secretary of the men’s fellowship. He was also the financial secretary of Christ Little Band-UK, one of the Ghanaian Fellowships, and a member of the Ghanaian Methodist Fellowship. Holding office was very important for him. He attained personal recognition and status, alongside the experience of acting as an official and mastering the bureaucratic language of the state. In John’s own words, he felt this enabled him to be an ‘active citizen’. When trying to encourage members to participate in the election for the Executive Committee of Christ Little Band-UK, John appealed to them: ‘You need to cast your vote, don’t be passive citizens, you need to take sides.’ Like in early post-independence Ghana, associations in the UK are often ’schools of citizenship’ (Wallerstein 1964). As such they are important spaces for nation-building. Within the church John has made many new friendships and considerably extended his network. Praised for his caring nature and much loved because of his good humoured disposition, he was able in less than five years to become a respected and popular member of the Ghanaian Methodist community in London. Through his relentless work, spiritual support and attendance at services he carved out for himself an important position denied him in the national public sphere, despite working in menial jobs. Most recently John was nominated a patron of the Susanna Wesley Mission Auxiliary UK branch (SUWMA-UK), arguably the most active Ghanaian Methodist fellowship in Britain. From its beginning in Ghana the fellowship has always been associated with middle-class, successful women and this is also 20 the case in London where the majority of the members are prominent professionals and businesswomen who settled in London over a long period of time, starting in the 1960s (see Fumanti 2010). The position of patron was one that John desired very much. He felt very proud of his achievements when the title was conferred on him in an official ceremony at Westminster Central Hall in the presence of both British and Ghanaian church Ministers. Being associated with the fellowship as their patron was symbolically a great step: he had been bestowed a role of patronage over a group of prominent women who had lived in London for a lengthy period. As patron, John had joined an illustrious roll call of patrons, sharing his title with traditional chiefs (nana), Methodist Ministers, successful and wealthy businessmen and women, doctors, lawyers and professionals. This was certainly testament to John’s effective work in the church but it also pointed to the social and cultural continuity of different waves of Ghanaian migrants over a forty-year period, and their continuous engagement with Ghana and Ghanaian Methodism. John had not been ostracised by the ‘early comers’, but had been incorporated and accepted as a member of Ghanaian Methodism to which even the first settlers in Britain remained connected. The London branches of Ghanaian fellowships mediated their long-term commitment to Ghanaian charitable and development projects initiated by the church. John, therefore, like other Ghanaian Methodists in London, actively pursued the ideal of the virtuous citizen through his involvement in the life of these fellowships, their rituals and congregational meetings. He paid his tithe regularly, and donated generously during service for local and international causes, including development initiatives in Ghana. He also contributed towards funeral expenses and other important rites of passage that sustained the sociality of Ghanaians in London. John went a step further, however, in displaying his care and nurturing side: he carved out for himself the role of mentor and counsellor to many of his fellow church friends. In fact, he stressed that his name meant ‘Good Counsellor’. He told me 21 with great pride how he spent hours on the phone talking to church friends, giving advice and support, praying or simply conversing: ‘Ah, last night when I came back from work I didn’t sleep,’ he would often tell me. ’I was on the phone with Auntie Grace, we chatted until six in the morning, we prayed, we consoled each-other, we chatted, we laughed... ahh it was beautiful.’ Of course, John was not the only African in London who spent many hours on the phone with friends. The long distances of travel to work, the very demanding work hours, and the isolating experience of a city like London, did not leave many opportunities to socialise outside church meetings. In London, the telephone plays a central role in communicating with others (see also Harris 2005). Pursuing the ideal of the virtuous citizen is not easy, and it was fraught for John with contradictions and limits. His generosity was not simply an act of selfless dedication. It enacted the Christian notion of generous giving in a system of obligation and indebtedness stretching between Ghana and London. Paying tithes in the church and donating generously are conceptualised by Ghanaians in instrumental terms as a transaction with God. This is spoken of as the planting of seeds that will eventually yield a great harvest, bringing wealth to the harvester. The idea is intrinsic in Protestant ethics, where wealth is a positive value to be pursued, but is particularly accentuated in present-day Ghanaian Methodist philosophy as a consequence of the growth and influence of the Pentecostal gospel of prosperity in Ghana and Africa more generally (Gifford 2004). The transactional nature of these donations is also culturally consonant with practices of gift exchange among Ghanaians. This is best described by the Twi expression, gye to ho mame. Roughly translated it means ‘keep it for me when I need it’. Gye to ho mame is an expression that accompanies donations in the course of funerals and other important life events. Through this expression the donor establish a link of interdependency with the receiver, creating indebtedness and future expectation of reciprocity. The more one donates the more the return. This is also the logic that infers the 22 contribution for welfare schemes in the Methodist Christian Fellowships. One member put it in these terms: ’A lot of people attend many associations and fellowships because of what they get in case of bereavement, or weddings and such… you know, it is really a lot.’ Discussing the benefit of the proposed ‘Ghanaian Methodist Fellowship welfare fund,’ the chaplain brought this point home very clearly: ‘The fund would be there to help each other in time of need for the members and also others in the church, if you don’t want to pay then it is up to you, but you know NCNC… No Contribution, No Chop… if you don’t pay you don’t benefit.’ Belonging to a Christian fellowship, like any other association, is a way to contribute to the common good in Ghana and the Diaspora, but is also insurance in case of personal need to respond to contingencies and unplanned or sudden events occurring in the family, abusua. Because funerals are central to Ghanaian and Akan sociality, raising funds and donations towards funeral expenses is very important. The contributions help organise funerary rites in which the life of the deceased is celebrated and the needs of the living are strengthened and recognised through care, nurturance and mutual relations. Gye to ho mame, keep it for me when I need it, is then a long term investment, based on mutual trust, establishing mutuality and exchange among donor and recipient. John’s donations, like those of other Ghanaians in the diaspora, included relations stretching between London and Ghana. Among these, kin demands to remit home remained a central concern. For John and other overstayers who were unable to travel to Ghana, the financial demands were particularly compelling and sought after. Encapsulation, Suspicion and Trust John’s virtuous achievement as a citizen was confined within the Ghanaian fellowships. As an overstayer, although he paid taxes he was not a particularly law abiding British subject. He 23 had broken the law by remaining after his visa had expired and had sought ways to gain citizenship illegally through an arranged marriage, even though he was already married. Within their fellowships, he and fellow Ghanaians worshipped exclusively in Twi, and used a liturgy borrowed from Ghana, setting themselves apart from other British Methodists. Although they also worshipped regularly in multicultural congregations, the scope in these for the formation of long-term inter-ethnic relationships was rather limited. Ghanaians tended to dissociate themselves from other ethnic groups, especially other black minorities in the church. They did so to distinguish their achievements in Britain and their moral standings as virtuous citizen in opposition to those who are perceived as bad achievers and unlawful. In particular they distanced themselves from Caribbean and Nigerian, depicting them stereotypically as unruly, unlawful, violent and bad achievers, a threat to Ghanaian values, especially for the younger generation. As one parent told me: ‘Our kids, you know when they hang around, they get really influenced by these other black kids, and they influence them badly, especially the Caribbeans, their kids don’t do well in school.’10 The Ghanaians I met, especially those who came to London as students, stressed the poor levels of education of Caribbeans in particular. This was a common view among Ghanaians, who prided themselves on their level of education. One of my informants, Attah, recalled: To be honest when I arrived I couldn’t understand a word of what they were saying. At first it was fine but then things started to go wrong. I think they saw us as better achievers than them... you know... I think that the problem is one of education... When they arrived they did not have a lot of education. They could not get the job they wanted to do, but only low skilled jobs because at the end of the day that was the only job they could do, bus drivers, cleaners and so on. So they were not very educated and their children as well could not be educated. Also a lot of them [the 10 Mary, London, November 2007 24 children] are from single parents and so it is more difficult, so it is really something that keeps perpetuating [itself]. I don’t blame them but it is what happened I think. I think sometimes they always think society is against them. Sometimes it is but not all the time, it’s not society’s fault11. Even though recent economic migrants from Ghana are employed in menial jobs, they share these same views on education as the pioneer diasporic Ghanaians in London. For Ghanaians in London trust, gyade, is critical to their social relations. Gyade regulates friendships and is particularly important in the diaspora for those without proper documentation. Gyade binds people to another in reciprocal mutuality and it is sanctioned morally through the creation of fictive categories of kinship. Ghanaians use kinship terminology, both in Twi and English, to sanction these relations, such as nua, brother/sister, when belonging to the same age group as ego, uncle/auntie when belonging to an older generation than ego. These are common and endearing terms of respect among individuals belonging to different age groups term. The same concept is also used to establish relations with other ethnic groups. When it comes to issue of trust, or gyade, Nigerians are at the top of the list in terms of unreliability. They share negative stereotypes with Caribbeans, but they are depicted in addition as wealthy, successful, actively involved in public life, loud and exploitative. Their wealth is seen as coming from corrupt deals and financial scams, the famous 419 is often mentioned (Smith 2001). Hence Ghanaians are generally suspicious of Nigerians and try to distance themselves from them. Yet for those Ghanaians who want or need to manipulate the system, Nigerians are also revered as they are seen to know all the legal loopholes that enable the acquisition of whatever documentation is required. Thus lack of trust linked to ethnic stereotyping contributes to Ghanaian encapsulation. At the same time they construct 11 Interview with Attah, London, December 2007 25 Ghanaian identity as virtuous and trustworthy. There are thus clear limits to the reach of humanistic values such as ɔtema empathy, and Christian compassion. Yet setting limits to empathy and compassion is highly problematic for a Christian institution like the Methodist church, which regards ethnic stereotyping and encapsulation as a problem. Hence, paralleling the wider national debate on immigration and multiculturalism in contemporary Britain, a similar debate is currently taking place within the Methodist Church, focused on the increasing number and role of ethnic minorities, especially of Africans within the church, and their possible threat to ‘church cohesion’. Methodism, Multiculturalism and Citizenship The Methodist church, especially in London, has been reflecting on and debating the role of ethnic minorities for a long time, at least since the 1970s. Through the work of a number of progressive ministers working in inner London, the church has recognised and allowed for the growth of ethnic minorities fellowships to cater for the spiritual needs of different congregations (Frost and Jordan 2006). Also, contending with its own past of discrimination12, the Methodist church has been a strong force against racism. In London, the church has provided a space supporting the numerous and growing ethnic minority communities, including the recent recognition of new ‘ethnic’ chaplaincies (Ghanaian, Nigerian, Zimbabwean, Sierra Leonian, Korean and Chinese). Their tendency towards encapsulation has, however, prompted a fresh debate on ‘church cohesion’. The issue emerged publicly in 2007, at a Methodist conference held in Derbyshire. The exclusionary tendencies of their fellowships has also a growing concern for the Ghanaian chaplaincy which at times must struggle to reconcile Ghanaian exclusiveness with a more inclusive loyalty to all members of the British Methodist Church and, more generally, Britain. 12 See in particular. Only One Race- the Human Race: Sybil Phoenix and Racism Awareness, in Frost and Jordan 2006, pp.202-214. 26 Between February the 2nd and the 4th 2007 the World Church Forum (the international office of the Methodist Church) hosted a conference in Derbyshire entitled ‘Ethnicity, Cohesion and the Church’. As one Methodist minister explained to me, this conference came about to address several issues. The first was the increasing use of Methodist church buildings by other Christian denominations. Methodist ministers across the country reflected on the absence of any interaction between Methodist congregations and these non-Methodist Christian communities: ‘We just knew them as our users but we wanted to know more about them as they are using our premises.’13 Letting out premises to other Christian denominations is a common practice in Britain. With the increasing number of socalled Independent churches, there is a need for more religious buildings across the country, and it is common to have two or more denominations holding their services in the same building on any given Sunday. The spatial proximity of other Christian churches, often Black churches, opened up, in the words of this minister, the need to reflect more widely on the increasing role of ethnic minorities within Methodism. It is now well accepted by British churches that without the presence of migrants, Methodism and other Christian denominations in Britain would be moving towards ‘extinction’. With the dwindling numbers of white Methodists, the majority elderly members, this is especially so in large urban areas, while churches have been closing down across the country. The arrival of migrants has changed the tide. But the reflections within the Methodist church are not just practical. They involve a deeper reflection on race, ethnicity and the teachings of Methodism that parallel wider debates on multiculturalism and race within British society. During the course of March 2007 I interviewed a number of different ministers who had taken part in the conference: four from Africa, (from Kenya, Zimbabwe and Ghana) and two white British. They all expressed their 13 Interview with Reverend J, Leicester, March 2007 27 concern over these issues, some more clearly than others. On the one hand, the English ministers expressed a sense of moral debt and guilt for the past attitudes of the Methodist church. One minister pointed out to me that the Methodist church, like other denominations, bore responsibility for the way in which race was handled in Britain. Recalling the rejection of Black Caribbean members in their congregations she said: I think the Methodist church has responsibilities in that. There are countless accounts of how Black members were rejected from the congregation and told to go and attend the church down the road. I think it is time that the Methodist church confronts that past of racial discrimination and recognises the role of all the different migrant groups in the church today. We shouldn’t repeat the mistakes we made in the past. (Interview with Reverend J, Leicester, March 2007)14. The legacy of racial discrimination and the changing attitudes of the church have consequences for the relationship between Caribbean and Africans. Many of the Ministers conceptualised the tense relationship between the two communities as linked to the fact that while Caribbeans had experienced open, prima facie racism and discrimination, African congregations were more easily accepted within the changing multicultural context of contemporary Britain. The Caribbeans had to fend for themselves while for Africans, there was the example in London of two very large established Korean and Chinese fellowships, which meant that they had an “easier” path towards recognition. This created a sense within the Caribbean community of a possible takeover of the church by newly arrived communities, and lack of acknowledgement of their role in the fight for racial equality in Britain. In remembering the inauguration of a Ghanaian fellowship in a Methodist church in WestLondon, Kweku stressed this point: ‘When we formed our fellowship you could just imagine what happened, the Caribbeans started to complain that we were taking over, that we wanted 14 A similar point was also made by another British Minister, J.P., London, February 2007 28 to impose our views.’ When it comes to contending with the church history of racial discrimination and the legacy of the slave trade, Caribbeans regard Ghanaians and other Africans equally responsible. It is a painful history, and more than one minister in London has tried to redress this historical divide by taking Caribbean and Africans members of their congregations on educational trips of Ghana and the Caribbean. One African Minister told me emphatically: There is not a good relationship among them... so I thought that slavery could have been a key issue in rebuilding trust in the congregation. So we decided to go to Ghana, many of the Caribbean members went and it was nice, they met with the relatives of our Ghanaian members there and we all went to the Fort where the slaves came from. It was very moving for us all, we all embraced each other and cried and they could see we were part of a system, we were victims too, so after that the mood in the congregation really improved. (interview, Reverend D. October 2006) The final motive which has moved the Methodist church towards a more open debate is the fear of schismatic tendencies within the church. Methodism was historically a schismatic movement of the Anglican Church15 and for two centuries, from the mid 18th century until the 1930s,16 British Methodism was composed by a series of different denominations more or less linked to Anglicanism.17 At the end of the 1800s, American Methodism departed from British Methodism and only in 1932 were all these groups reunited under the umbrella of one Methodist church (Vickers 2000, Davies & Rupp 1965). Methodism is also notable for the freedom given to its different ministers to pursue their own theological work. Such a freedom runs the risk of encouraging the emergence of charismatic 15 Dreyer (1999) however argues that the genesis of Methodism should be found in the Moravian church. It is scholarly acknowldeged that Methodism was born on 23/07/1740 (Dreyer 1999). This is the date in which John Wesley and a small group of friends assembled in the London suburbs of Moorfields and started the movement. 17 The Final Deed of Union was reached on 20/09/1932 bringing together the Wesleyan Methodist Church, the Primitive Methodist Church, the United Methodist Church to form the denomination formally known in today as the Methodist Church of Great Britain. 16 29 leaders within the church, especially in the context of the African diaspora. The conference and the current debate highlight the concerns within British Methodism regarding possible tendencies towards the formation of independent churches. While recognising the different fellowships, the conference’s concern was how these fellowships should work together for the strength and good of the Methodist Church. The message that emerged was clear: express your differences, the fellowships are spaces for that, but remain committed to British Methodism. Help maintain cohesion in the church while expressing and celebrating your different cultural backgrounds. Ghanaian Methodists in London had had their own schism, following the official appointment of the Ghanaian chaplain. A group portraying itself as founders of the Ghanaian Methodist Fellowship worshipped for a while separately from the rest of the congregation under the leadership of a Ghanaian preacher, not himself a Methodist, who was using the premises of a Methodist church to conduct services. The British Methodist church stepped in through the appointed Ghanaian chaplain and demanded the removal of this self-appointed minister on the ground that he was not appointed by the church. More importantly, he was not a member in any Methodist church either in London or Ghana. Not being a Methodist and belonging to the church polity disqualified him immediately from the role or preacher. Methodism has at its core the idea of being a polity. ’This is the bedrock of Methodism,’ a minister told me.18 The polity is regulated by membership cards, which each member carries. The card functions like an ID or Passport. One Minister explained: ‘The membership card is very important because if you move house and go somewhere in the country or other parts of the world where there are Methodist churches, you would carry your card. We would also write a letter to the local Ministers to introduce you to them [the 18 Interview Reverend J.P., London, February 2007 30 congregation].19’ Methodism as a polity requires forms of identification but also a certain idea of citizenship both within and beyond the wider polity. It is an idea of citizenship that allows for flexible citizenship, (Ong 1998) but as it is confined within the limits of a religious institution. Debating belonging within Methodism is a way of debating one’s role within British society and transnationally, with Ghana. The debate has led Ghanaians to reflect on their role in British society and the legitimate limits of their own encapsulation. A few days after the conference, one minister, who had attended with three other Ghanaian Methodists, reflected on the long term sustainability of the Ghanaian fellowships which are failing to attract the younger generation and newer migrants: There is a risk that we would disappear in a few years’ time. Maybe the language is a problem, to do it in Twi (i.e. to hold the services). You see, there are a lot of new fellowships in the church and they are impressive really. The Zimbabweans are very active, there is soon to be a Nigerian fellowship. But the Chinese and the Koreans, they are really strong. You know how the Chinese call themselves? The BBC… British Born Chinese…we need to show the British Methodists that this fellowship [the Ghanaian] is effective and viable… you know, or there would not be funding for us any longer as a fellowship.20 His comments reflect the view of some Ghanaians Methodists that integration is preferable to absolute encapsulation. The joke on the Chinese BBC is an ironic recognition that encapsulation has its limits. Access to the Methodist church is a sign of recognition and acceptance within British society, so losing that recognition is something diaspora Ghanaians do not want to risk. Exclusion from the church would indicate doubt over their allegiance and loyalty to Britain and ultimately on their right to claim citizenship. Against the suspicion surrounding ethnic fellowships and the fear of takeover one friend told me: 19 20 Interview Reverend A.O, London, November 2006 Interview with K.A., London, March 2007 31 You see, I don’t think that people understand what we wanted. Our idea was to promote a positive image about ourselves, our culture and traditions, the way we work together and how we can contribute to the church and the community we live in. This is our idea of integration. Not separation. They thought we wanted to discriminate and separate ourselves, but we wanted to integrate. (Kweku, interview May 2007). Acquiring recognition through difference, as distinctively Ghanaian Methodists, is central to the process of integration within the Methodist church and Britain at large. This echoes Charles Taylor’s point (1994) in his ‘politics of recognition’ that groups have the right to defend and promote their cultural identities, since it is these which grant them a sense of equal dignity. Their shared organisational links and common heritage as Methodists means that Ghanaians feel simultaneously incorporated both into Ghana and the United Kingdom. This dual heritage defines flexible citizenship within the space of a transnational religious institution. Within it loyalties are secured and so is a sense of belonging. Minister Ogoe stressed these interelationships during the inauguration of the Ghanaian choir in London: Let us remember who we are. You are a choir within the Ghanaian Methodist Fellowship. The Ghanaian Methodist Fellowship is part of the Methodist church. First and foremost our duty is to the British Methodist church as we live in this country and this is our place of spiritual nourishment. But we are also part of the Ghanaian Methodist church as Ghanaians. So whatever you do for the fellowship you do it for the Methodist Church. Let us not forget your service to the Methodist Church as a whole and to this country in particular. (Reverend Ogoe, London, August 2008) The Minister underlines in his speech the limits of legitimate encapsulation and the negotiated construction of virtuous citizenship within the church. The Ghanaian Methodist Fellowship is at present coming to terms with the need to engage with more inclusive 32 practices of active citizenship. They have become conscious of the necessity of counter what appears to be an ethnic takeover, but they are also competing for prominence with other African and Asian fellowships by showing that they are working hard to achieve permanent roots in multicultural Britain, tolerant of diversity. In order to survive, they need to show that they are here to stay. Hic Manebimus Optime, we will settle here as best as we can, the Latins used to say. Conclusion: Virtual Citizens, Virtuous Citizens Akan speaking Methodists in London make sense of their diasporic experience through an idea of citizenship built around the idiom of virtue. Regardless of their legal and formal status, these migrants feel that they are virtuous citizens of Britain, to which they feel they belong as Methodists, workers and law-abiding subjects, while remaining doubly rooted, in Ghana and in Britain. Active membership in the British Methodist church provides the context for the formation of this alternative construction of citizenship. ‘Virtuous citizenship’, I have proposed, is rooted in the Methodist Christian ideology of universal and selfless love and in the Akan concept of empathy, ɔtema. ɔtema empathy for the pain of others, is at the basis of Akan personhood and sociality, expressed through moral and material obligations to humanity at large, and more narrowly to family, abusua, and fellowship members. These fellowships place great emphasis on welfare, mutual assistance, and nurturing. It is in the course of church activities public events,and rituals, most notably funerals and birthdays, that these obligations are performed. Despite their ideal of ‘virtuous citizenship’, however, Ghanaian Methodists live highly encapsulated lives, distancing themselves from other black ethnic minorities. By advancing a synthesis between feminist and Aristotelian conceptualisations of citizenship I have shown, through the case of one migrant overstayer, that ‘virtuous’ and ‘virtual’ 33 citizenships are not irreconcilable in the minds of British Ghanaians but are part of the same alternative construction of citizenship. Virtuous citizenship, even when virtual, is actively sought by Ghanaians Methodists in London as they try to emerge as a distinctive group within the Methodist church and Ghanaian diaspora. By making their way in the Methodist church, Ghanaians feel that they are emerging and contributing to British life even if they do so from their positioning as an ethnically marginal, exclusive and encapsulated community. Encapsulation in ethnically exclusive fellowships remains, I have shown in this paper, a highly problematic concept for the British Methodist Church whose internal debate mirrors wider debates in Britain on multiculturalism and immigrant citizenship. At the same time the church has tried to promote an idea of active and communitarian citizenship among its various migrant ethnic fellowships. Ghanaians themselves are becoming increasingly aware of the critique of encapsulation, but from their point of view ethnic fellowships do not imply exclusion of exclusiveness: they are the loci where people’s agency is experienced, and where people gain recognition, distinction and visibility, often in contrast with their lives outside the church. It is there that they make a valuable contribution to the British Methodist church. The fellowships allow Methodist Ghanaians to remain doubly rooted, in Ghana and Britain, as flexible postcolonial virtuous, if at times virtual, citizens. And it is in addressing the paradoxes of flexible citizenship as it is experienced within the limits of a religious institution that this paper aims to bring a fresh contribution on the themes of multiculturalism, transnationalism and diasporic citizenship. References Akyempong, E. 2000. Africans in the Diaspora: the Diaspora in Africa. African Affairs, Vol. 99, pp. 183-215. Aristotle 1950. The Politics of Aristotle. 3 volumes Oxford: Clarendon Press. 34 Assiter, A. 1999. Citizenship Revisited. In Women, Citizenship and Difference, Werbner P. and Yuval-Davis N. (Eds.), pp. 41-53. London: Zed Books. Adkins, A. W.H. 1963. Friendship and Self-Sufficiency in Homer and Aristotle. The Classical Quarterly, Vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 30-45. Bartels, F.L. 1965. The Roots of Ghana Methodism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. D’Alisera, J. 2004. An Imagined Geography: Sierra Leonean Muslim in America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsilvanya Press. Davies, R. And Gordon, E. (Eds.) 1965. History of the Methodist Church in Great Britain. Peterborough: Epworth Press. Develin, R. 1973. The good man and the good citizen in Aristotle’s “Politics”. Phronesis, Vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 71-79. Dreyer, F. 1999. The genesis of Methodism. Parker, PA: Leigh University Press. Donlan, W. 1973.The origin of kalos kai agathos. The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 94, no. 4, pp.365-374. Etzioni, A. 1993. The Spirit of Community: Rights, Responsibilities and the Communitarian Agenda. New York: Crown Publishers. Frost, B. and Jordan, S. 2006. Pioneers of Social Passion: London’s Cosmopolitan Methodism. Peterborough: Epworth Press. Fumanti, M. 2009. Immigrazione, associazionismo e cittadinanza: il caso di due associazioni Ghanesi a Londra, Afriche e Orienti, Vol. 1, no. 3/4 (in press). Fumanti, M. 2010. Irreverent piety and gendered power in the London Ghanaian diaspora: the case of the Susanna Wesley Methodist fellowship. Africa, forthcoming. Gifford, P. 2004. Ghana’s New Christianity: Pentecostalism in a Globalising African Economy. London: Hurst. 35 Grillo, R. and Mazzucato, V. 2008. Africa < > Europe: a double engagement. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, Vol.34, no. 2, pp. 175-198. Halevy, E. 1971. The Birth of Methodism in England. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Harris, H. 2006. Yoruba in Diaspora: an African Church in London. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Krause, K. 2008. Transnational Therapy Networks among Ghanaians in London. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, Vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 235-251. Lister, R. 1997. Citizenship: towards a feminist synthesis. Feminist Review, Vol.57, pp. 2848. Marshall, T.H. 1964. Class, citizenship and social development. New York: Doubleday. Mayer, P. 1971. Townsmen, or tribesmen: conservatism and the process of urbanization in a South African city. Cape Town and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Mazzucato, V. 2008. The double engagement: transnationalism and integration. Ghanaian migrants’ lives between Ghana and the Netherlands. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, Vol.34, no.2, pp. 199-216. Mengestu, D. 1997. The Children of the revolution. London: Jonathan Cape. McGregor, J. 2007. Joining the BBC (British Bottom Cleaners): Zimbabwean migrants and the UK care industry. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, Vol.33, no. 5, pp.801-824. McGregor, J. 2008. Abject spaces, transnational calculations: Zimbabweans in Britain navigating work, class and the law. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, Vol. 3, no. 4, pp.466-482. Mohan, G. 2006. Embedded cosmopolitanism and the politics of obligation: the Ghanaian diaspora and development. Environment and Planning A., Vol. 38, no.5, pp.867883. 36 Monks, J. 1999. “It works both ways”: belonging and social participation among women with disabilities. In Women, Citizenship and Difference, Werbner P. and Yuval-Davis N. (Eds.), pp. 65-84, London: Zed Books. Newell, W.R. 1987. Superlative virtue: the problem of monarchy in Aristotle politics. The Western Political Quarterly, Vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 159-178. Ong, A. 1999. Flexible Citizenship: The cultural logic of transnationality. London and Durham: Duke University Press. Page, B., Mercer, C. and Evans, M. 2008. Place and the politics of home: development and the African Diaspora. London: Zed Books. Prokhovnik, R. 1998. Public and Private Citizenship: From gender invisibility to feminist inclusiveness. Feminist Review, Vol. 60, no. 1, pp. 84-104. Putnam, R.D. 2000. Bowling Alone: the Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster. Riccio, B. 2008. West-African transnationalisms compared: Ghanaians and Senegalese in Italy. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, Vol. 34, no. 2, pp.217-234. Selvon, S. [1956], 2000. The Lonely Londoners. London: Penguin Books. Smith, A.J 2001. Ritual killing, 419 and fast wealth: inequality and the popular imagination in Southeastern Nigeria. American Ethnologist Vol.28, no. 4, pp. 803-826. Stasilius, D. & Bakan, A.B. 1997. Negotiating Citizenship: the case of foreign domestic workers in Canada. Feminist Review, Vol. 57 (autumn), pp.112-139. Stoller, P. 2002. Money has no Smell: the Africanization of New York City. Chicago: Chicago University Press. Taylor, C. 1994. The politics of Recognition. In Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition, Taylor, C. and Gutmann, A. (Eds.), pp. 25-74, Princeton: Princeton University Press. 37 Ter Haar, G. 1998. Halfway to Paradise: African Christians in Europe. Cardiff: Cardiff Press. Van Djik, R. 1997. From Camp to Encompassment: discourses of transsubjectivity in the Ghanaian Pentecostal Diaspora. Journal of Religion in Africa, Vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 135-159. Vasta, E. & Kandilige, L. 2007. “London the leveller”: Ghanaian work strategies and community solidarity. COMPAS, Oxford working papers WP-07-52. Vickers, J. A. (Ed.) 2000. A dictionary of Methodism in Britain and Ireland. Peterborough: Epworth Press. Wallerstein, I. 1964. The road to Independence: Ghana and the Ivory Coast. The Hague: Mouton. Werbner, P. 1990. The Migration Process: Capital, Gifts and Offerings among British Pakistanis. Oxford: Berg Publishers. Werbner, P. 2002. Imagined Diasporas among Manchester Muslims: The Public Performance of Pakistani Transnational Identity Politics, World Anthropology Series. Oxford: James Currey Publishers and Santa Fe: New School of American Research. Werbner, P. & Yuval-Davis, N. 1999 “Women and the New Discourse of Citizenship”, in Women, Citizenship and Difference, Werbner, P. & Yuval-Davis, N. (Eds.), pp. 138. London: Zed Books. Whyte, W.F. [1943] 1993. Street corner society: the social structrure of an Italian slum. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 38