UNIT OF STUDY 1

advertisement

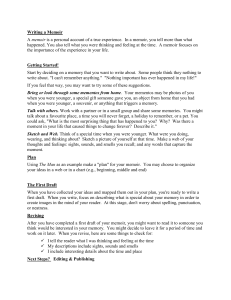

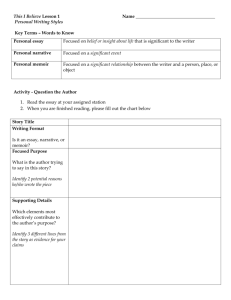

UNIT OF STUDY 1: Raising the Level of Narrative Writing Grade 7: Memoir The focus of this unit of study is the memoir. Through study of the memoir, students will revisit the classroom routines and rituals for a writing workshop. They will add to their writer’s notebooks in order to build an arsenal of ideas for this unit of study as well as upcoming units. In the first week, students will mine their lives for ideas by using a variety of strategies to generate ideas for their memoir. They will select one idea and in one classroom setting produce a full draft. For the next few weeks, they will write a second and perhaps a third draft, moving through the revision and editing process while studying mentor text. The mentor text will teach them how to tell stories rather than summarize, focus their stories on one important event in their lives, and reflect on the significance of those events. Eventually, they will publish their memoir. ENDURING UNDERSTANDING(S) – What big ideas do students need to know well? What big ideas are transferable to other situations? Through writing we can better understand the significance our lives. Everyone has a powerful, interesting, unique story to tell. Mentor texts help us craft our stories in a way that others will care. The writing process can lead to surprises and discoveries. ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS: How am I special? What’s unique about me? How’s my story unique? What can I learn and others learn from my story? How do I get others to care about my story? How can we make this best possible year for us as writers? How can we support each other as writers? Focus of unit of study: What will students inquire about (e.g., a genre, the writerly life, an author)? Memoir and supporting each other as writers What standards/benchmarks will your unit address? (Power standards -- bold) Writing strand: 1.1 (topic, purpose, audience) Media literacy: 3.2 1.2 (generating ideas) Oral communications: 1.2 (active listening strategies) (interactive strategies) 1.4 (classifying ideas) | UNIT OF STUDY 1: Raising the Level of Narrative Writing: Grade 7 Based on Teachers College Reading and Writing, Middle School Writing Calendar, 2008-9 2.2 1 1.5 (organizing ideas) 2.2 (voice) 2.5 (point of view) 2.7 (revision) 3.4 (punctuation) 3.6 (proofreading) 3.8 (producing finished works) 4.1 (metacognition) At the end of the unit of study, students will KNOW…. Memoir is recounting a story about one’s life and answering the question “So what?” The difference between memoir and personal narrative Various ways to organize memoir, including chronological order, flashbacks, use of text features (e.g., white space to separate parts of the story, italics to tell a story from a time period different than the rest of the story) The importance of audience The difference between storytelling and summarizing At the end of the unit, students will be able to… Increase the volume of their writing Use strategies for generating ideas Focus their writing: writing about small moments and writing snapshots (Barry Lane) Generate and apply the features of a memoir (i.e., 1st person, reflection, snapshot, based on truth, focus on the author’s experience more than the event itself) Select a significant event in their life for their memoir Use a strategy, such as a timeline or storyboard, to plan a memoir Write from 1st person point of view Know how to use the truth to tell a good story Write in an authentic and sincere voice that engages the reader Use details so that the reader can make movies in his mind Actively listen to peers and provide meaningful response to the writing of others Punctuate and indent dialogue Use verb tense in a logical manner | UNIT OF STUDY 1: Raising the Level of Narrative Writing: Grade 7 Based on Teachers College Reading and Writing, Middle School Writing Calendar, 2008-9 2 Describe the performance task: What will student write? What will they write? Select one significant event in your life and write a memoir that your peers will read. Attach to your published memoir a writer’s memo that tells your story about how you wrote the memoir and your reflection on the quality of your writing. How will you provide feedback? Monitor student performance? Let students know how well they’re doing? Collect formative assessment? (Assessment for learning) Conferring, peer response, respond to drafts, tuning protocol, check list – generated by class Publication: Where might students publish their writing? Options: copies available for class to read; published book for classroom library; wiki; Glogster; online journals, such as Teen Ink Preparation for the unit of study: 1. Gather memoirs, to include complete texts and excerpts. 2. Select one as your classroom mentor text. 3. Make baskets of memoirs for close study (one basket per class table.) 4. Option: select a memoir as your class read aloud. 5. Continue to expect students to write a full page each night in their writer’s notebooks. Resources: For teachers: Teachers College Reading and Writing Middle School Units Bomer, Katherine. Writing a Life Calkins, Lucy. The Art of Teaching Writing, chapter 24. Fletcher, Ralph. Boy Writers, Craft Lessons, What a Writer Needs Kirby, Dan and Kirby, Dawn Latta. New Directions in Teaching Memoir Lane, Barry. Reviser’s Toolbox Lattimer, Heather. Thinking Through Genre, chapter 3 Ray, Katie Wood. Study Driven The Milestones Project: Celebrating Childhood Around the World | UNIT OF STUDY 1: Raising the Level of Narrative Writing: Grade 7 Based on Teachers College Reading and Writing, Middle School Writing Calendar, 2008-9 3 The Milestones Project website: http://milestonesproject.com/index.php/milestuff A series of articles about the genre of memoir and tips for writing and teaching the memoir: http://www.thewritingsite.org/articles/vol4num2.asp For classroom use as mentor text: Abeel, Samantha. My 13th Winter Barron, TA. Where is Grandpa? Blume, Judy. The Pain and the Great One Bunting. Eve. Fly Away Home, Smoky Nights, The Memory String Chall, Marsha. Up North at the Cabin Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street Crutcher, Chris. King of the Mild Frontier Dahl, Roald. Boy: Tales of Childhood; Going Solo Ehrlich, Amy, ed. When I Was Your Age Fletcher, Ralph. Grandpa Never Lies; Marshfield Dreams Fox, Mem. Wilfred Gordon McDonald Partridge, “Motherhood” Hillen, Ernest. The Way of a Boy Lowry, Lois. Looking Back: A Book of Memories McLachlan, Patricia. All the Places to Love; Through Grandpa’s Eyes Myers, Walter Dean. Bad Boy Paulsen, Gary. Dogteam; Guts; Harris and Me; My Life in Dog Years; Woodsong Rau, Santa Rama. “By Any Other Name” Soto, Gary. A Summer Life Spinelli, Jerry. Knots in My Yo-yo String Other lists of memoirs in New Directions in Teaching Memoir, Kirby and Kirby and page 193-4 Study Driven | UNIT OF STUDY 1: Raising the Level of Narrative Writing: Grade 7 Based on Teachers College Reading and Writing, Middle School Writing Calendar, 2008-9 4 Topic/Concept Teaching Points The predictable structure of a workshop grows writers and thinkers. Through close study of mentor text, writers learn about genre and craft. Students understand the routines and rituals of a writing workshop: o A mini-lesson o Uninterrupted time to write o A time to debrief o The importance of conferences o The role of the writer’s notebook o The expectation that writing will be brought to publication o The use of mentor text The importance of a community of writers 1 JIS Standards and Benchmarks Assessment Strategies and Tools 1, 2, 3, 4 Through close study of memoirs, writers 2.2 Establish a distinctive voice in their writing appropriate to the subject and audience. generate and apply the features of a st 4.2 Describe how their skills in listening, memoir (i.e., 1 person, reflection, speaking, reading, viewing, and representing snapshot, based on truth, focus on the help in their development as writers. author’s experience more than the event itself) Reflection is what distinguishes memoir from personal narrative. Memoirists write small in order to convey meaning and to help readers make movies in their minds. Writers focus their writing by using snapshots interspersed with thought shots1. Memoirists know how to use the truth to tell a good story. Memoirists use story elements to tell their See Barry Lane, Reviser’s Toolbox | UNIT OF STUDY 1: Raising the Level of Narrative Writing: Grade 7 Based on Teachers College Reading and Writing, Middle School Writing Calendar, 2008-9 5 Memoirists mine their lives for story ideas and find significance in their lives. Writers use various strategies throughout the writing process to plan, organize, revise and edit. story rather than summarize. Writers study other writers to discover and experiment with writing craft. Each event in the memoir needs to lead the reader to understand the writer’s reflection on the significance of the events. Dialogue is powerful for the reader: keeps the reader interested, helps the reader make movies in his mind. Often we have to make up the dialogue but we need to be sure that it reflects the truth. 1.2 Generate ideas about more challenging Writers use their writers’ notebooks to topics and identify those most appropriate for generate ideas (e.g., neighborhood map, their purposes. writing territories, quick writes, double timeline). Writers review their writer’s notebooks to find a significant story and to identify themes that they can explore in drafts. Memoir includes a story of the past and answers the question “so what?” Why was this event significant? Writers rehearse ideas through a variety of 1.4 Sort and classify ideas and information for their writing in a variety of ways that allow strategies (e.g., talking, rewriting from a them to manipulate information and see different perspective, quick writes). different combinations and relationships in Writers plan their memoirs (e.g., time their data. lines, storyboards, outlines). 1.5 Identify and order main ideas and supporting Writers experiment with leads and ends details and group them into units that could often using mentor text as models. be used to develop a multi-paragraph piece Writers organize their writing in a variety of of writing, using a variety of strategies. ways, including chronological order, 2.5 Identify their point of view and other possible through flashback, and by shifting verb points of view, evaluate other points of view, tenses intentionally. | UNIT OF STUDY 1: Raising the Level of Narrative Writing: Grade 7 Based on Teachers College Reading and Writing, Middle School Writing Calendar, 2008-9 6 Writers reflect on their writing process and their drafts to determine if they meet their purpose and are appropriate for the audience. Writers edit for meaning and conventions. Writers deepen our understanding by discussing our writing with peers. Some writers use text features, such as space and italics, to convey a shift in time. The writer experiments with telling the same story to different audiences and for different purposes. The writer understands the important of audience. A writer identifies his audience and his purpose (e.g., to entertain, to explain an insight, to be a role model). A writer’s memo conveys the writer’s story of how a piece came to be and identifies writer’s intentions and assessment of whether the writing met the writer’s intentions. and find ways to acknowledge other points of view, if appropriate. 2.7 Make revisions to improve the content, clarity, and interest of their written work, using a variety of strategies. 4.1 Identify a variety of strategies they used before, during and after writing, explain which ones where most helpful, and suggest future steps they can take to improve as writers 3.4 Use punctuation appropriately to communicate their intended meaning in more complex forms 3.6 Proofread and correct their writing using guidelines developed with peers and the teacher The conventions of writing dialogue help the reader make sense of the memoir. A well-edited story ensures that the reader’s attention is on the story itself and not distracted by errors. A well-edited memoir shows respect for the reader. Partners develop skills in active listening, including turn taking, posing questions, and making suggestions in a tactful manner. 1.2 identify a variety of listening comprehension strategies and use them appropriately before, during, and after listening in order to understand and clarify the meaning of increasingly complex or challenging oral texts | UNIT OF STUDY 1: Raising the Level of Narrative Writing: Grade 7 Based on Teachers College Reading and Writing, Middle School Writing Calendar, 2008-9 7 Additional support A FRAMEWORK FOR MINI LESSONS2 Or How to Use Assessment to Inform Instruction Connect – Explain to students how your lesson connects to their work and/or reflects an assessment. Teach – Teach the concept, skill, strategy, or technique. Have A Go – Encourage students to try out the concept, skill, strategy, or technique. Link – Connect the mini-lesson to upcoming work. SAMPLE MINI LESSON: Using a Mentor Text Note: the two following lessons will be your longest mini-lessons in this unit. Connect – We’re read lots of memoirs plus you’ve been writing your memories in your writer’s notebooks every day. Today we’re going to study one of our mentor texts, Up North at the Cabin by Marsha Chall, and look closely at her writing. We learn how to become better writers by studying good writing. Teach – This part of writing a memoir is called a close study. We’re going to read like a writer and then try to write like this writer. I’ve put each page on a power point slide so we can closely study and notice Marsha Chall’s writing. What does she do as a writer to bring her memory to life? How does she draw the reader in her memory of this special place and time? How does she show us that she lived richly up north at the cabin? As we read the pages, we’ll notice what she does as a writer and make an anchor chart so you can refer to it when you are writing drafts of your memoir. You can try to use her craft in your writing. [Read and discuss each page. Chart student noticings.] Have A Go – Let’s chose one page and think how you could make it your own. Think of one of your memories and envision how you might make it yours. Talk to your writing partner about what you might do. [Give them a short amount of time to talk.] When you return to your desk to write, try it out and see if you like it. Link – We have about 20 minutes to write and then we’ll gather to share our changes. I look forward to our debrief! 2 Thanks to Colorado Writing Project and Carl Anderson for this framework and for the sample mini lessons. | UNIT OF STUDY 1: Raising the Level of Narrati Based on Teachers College Reading and Writing, Middle School Wri A FRAMEWORK FOR MINI LESSONS3 Or How to Use Assessment to Inform Instruction Connect – Explain to students how your lesson connects to their work and/or reflects an assessment. Teach – Teach the concept, skill, strategy, or technique. Have A Go – Encourage students to try out the concept, skill, strategy, or technique. Link – Connect the mini-lesson to upcoming work. SAMPLE MINI-LESSON: FINDING A THEME, THE “SO WHAT?” Connect: You’ve been making lists, writing short entries, and collecting memories in your writer’s notebook. Writing memoir is so important because we learn about ourselves and the relationships we have with other people and places. When we reread our memories we find patterns or threads of meaning in our writing. I notice in my writer’s notebook that I write a lot about camping with my family when I was little. Those camping trips brought my mom, dad, brother and me together in a very special way, and I have tons of funny stories about those times. Teach: Today we’re going to read like a writer. First we’re going to read memoirs from three writers. I want you to listen and notice why each is important to the writer. At the end of our reading we’ll ask ‘so what?’ Why was this memory important to the writer? Sometimes the writer will tell us in her own words; other times you’ll have to infer why it was important. Next we’re going to look at all three and determine if there is a theme or thread that is common in the writing. [Give them the following from The Milestones Project (CA: Tricycle Press, 2004): The Playhouse (the playhouse and the nail are important symbols); the piece by Oscar Misle (the horse taught him about life, imagination, and happiness with simple things); and Punky Bear by Stephen Pankhurst (the bear is an important part of who the author is.) Discuss the common theme/thread. Point out that the writing is in present tense. Have-a-go: At the beginning of this lesson I mentioned my father’s influence on me. What I’m going to do is to write about one of our camping trips and show how we all worked together as a team when we pitched camp and went on our hikes. I want to show how important that working and playing together was for all of us. Now it’s your turn. Sit next to your writing partner and quietly reread your own writings. Read each entry thinking about what about that time was important to you Ask yourself ‘so what?’ Jot down on a post it what the writing tells about you. When you’re finished, reread your post-its, looking for a common theme or thread in your writing. Link: When you and your memoir partner are finished, quietly discuss and share what you learned about your writing. We’ll have about 20 minutes for this and then come back to debrief. Be ready to share at least one thread you found in your writing. 3 Thanks to Colorado Writing Project and Carl Anderson for this framework and for the sample mini lessons. | UNIT OF STUDY 1: Raising the Level of Narrati Based on Teachers College Reading and Writing, Middle School Wri A FRAMEWORK FOR MINI LESSONS4 Or How to Use Assessment to Inform Instruction Connect – Explain to students how your lesson connects to their work and/or reflects an assessment. Teach – Teach the concept, skill, strategy, or technique. Have A Go – Encourage students to try out the concept, skill, strategy, or technique. Link – Connect the mini-lesson to upcoming work. SAMPLE MINI-LESSON: WRITING DIALOGUE WITH PUNCTUATION Connect: You all are deep into writing your memoir. One thing I’ve noticed as I’ve been conferring with you is that many of you are using what we talked about in our power of dialogue mini-lesson a few days ago; however, you’re not using the punctuation that clues the reader in so sometimes the reader gets lost. I’d like for us to spend a little bit of time today revisiting how writers use punctuation in dialogue to make their writing more powerful. Teach: Remember when we studied the excerpt from Samantha Abeel’s My 13th Winter? Let’s look again at how she helped her reader understand when someone as speaking. Read this over to yourselves for a moment and see what you notice about how she helps the reader. [Give students time to read the excerpt.] What did you notice? [Chart their responses and guide them to notice indentation, punctuation, and speaker tags. If students need more than a reminder, you might highlight each speaker in a different color and then circle the punctuation. Continue reminding students how the conventions of indenting and punctuating dialogue help the reader make sense of the text.] Have a Go: You’ve all brought your drafts with you. Let’s take the next couple of minutes to go back to your dialogue scenes and check that those punctuation marks and commas are there. Be sure to check with your writing partner if you’re not sure. Link: When I come around to confer with you today, you can be sure I’ll be checking to see how effectively you are using punctuation in dialogue. Are you ready to get started? Okay, let’s go then. 4 Thanks to Colorado Writing Project and Carl Anderson for this framework and for the sample mini lessons. | UNIT OF STUDY 1: Raising the Level of Narrati Based on Teachers College Reading and Writing, Middle School Wri