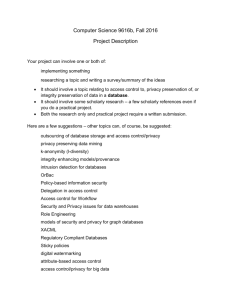

Privacy Tool Kit - American Library Association

advertisement