Introduction - University of Manitoba

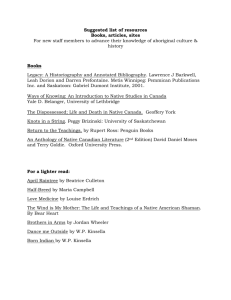

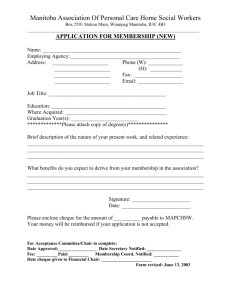

advertisement