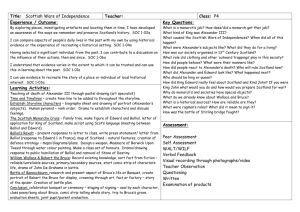

2006 Source Questions - Deans Community High School

advertisement

2006 Source Questions 1. Source A was written by historian and ‘Comyn’ specialist Alan Young. Young is likely to give a detailed, unbiased and therefore useful account of Balliol’s reign. Source A opens with Young discussing Balliol’s “inexperience and naivety”. Indeed this is completely justified. Here is a man who was destined for a career in the church and would have undoubtedly spoken with a strong English accent, thrust into a position of supreme power. Despite this, much of what we think of Balliol has been influenced by Bruce propaganda. After all, Bruce attempted to write Balliol out of history in the Declaration of Arbroath. The aspects of ‘naivety’ and ‘inexperience’ applied to Balliol stem from his dynamic relationship with Edward I. King John was coroneted at Scone on 30th November 1292; however, prior to this, he had already recognised Edward I as ‘overlord’ during the Great Cause. Interestingly, Robert Bruce; ‘the competitor’ had been one of the first to acknowledge Edward I as ‘overlord’. Certainly, power hungry Edward I would prove to be the source of many of Balliol’s problems. Young even states in the source that Balliol was: “no match for Edward I’s forcefulness”. Another reason Balliol could be accused of being naïve was in his releasing of Edward I from the promises he had made in the treaty of Birgham and during the Great Cause. All this evidence supports Ranald Nicholson’s comment regarding Balliol’s position – “Edward regarded him [Balliol] as a subject”. Ever since Balliol performed homage to Edward I in Newcastle on the 26th December 1292, he placed himself in an uncompromising and untenable position. Young goes on to mention that the Bruce faction would also become a persistent problem for Balliol throughout his three and half years on the throne. Robert Bruce, (grandson), for example refused to attend Balliol’s first parliament and avoided swearing homage to Balliol in August of 1293. Source B, on the other hand, is an extract from ‘The Later Middle Ages’ by Ranald Nicholson, another renowned academic historian. Source B begins by mentioning the role the Comyns played in John Balliol’s reign. The view that Balliol was a puppet of Edward I is misleading. Much more accurate is the view held by Michael Penman, that if Balliol was a ‘puppet’ at all, he was a puppet of the Comyns who propelled him into power. The Comyns embodied much of the patriotic spirit as Nicholson also points out. Source B also mentions that: “between 1293 and 1294 at least four parliaments were held”. This alludes to the fact that Balliol’s reign was marked with some semblance of success. It is true that annual parliaments were held under King John, which shows that despite Edward I’s best efforts, Balliol was able to keep some control over his kingdom. Despite Young’s and Nicholson’s accounts of Balliol’s reign, both miss out some of the finer details in regard to Balliol’s success. Reliable source evidence confirms that Balliol dealt with a backlog of legal cases whilst in power and made an effort to continue to work of Alexander II and III by creating sheriffdoms in the west-coast, shires of Kintyre, Argyll and Skye. Balliol’s various French connections also helped bring trade and prosperity to Scotland. Fiona Watson also suggests that Balliol must have been involved the ‘Auld Allaince’ due to these French relations. Clearly Balliol did not just blindly submit to Edward I. Overall, both sources provide key insights to the reign of John Balliol, and despite missing out some of the finer details, both represent helpful sources of information. 2. Source C is an extract from ‘The Brus’ by John Barbour, famous Scottish patriot and archdeacon of Aberdeen. Barbour, writing fifty years after the events he describes, relies a lot on myths and stories to form the basis of ‘The Brus. As such, questions over the reliability of the source emerge. Despite the obvious bias, ‘The Brus’ does give a great insight into Robert I’s military strategy and tactics. The focus of Source C is very much Robert Bruce’s policy towards castles and Scottish tactics when it came to re-capturing castles occupied by English garrisons. The source describes how Bruce destroyed castles to avoid them falling back into the hands of the English. The fact remains that Bruce did not have the manpower or resources to garrison captured castles. Geoffrey Barrow has highlighted the unusual nature of these tactics. Bruce had to rely on guerrilla tactics and surprise skirmishes when it came to facing the English, certainly in the early part of his reign. Bannockburn was the exception to the rule. It can also be suggested that the success of the guerrilla tactics was born out of a necessity. This underlying weakness does not subtract from the obvious success that Bruce enjoyed. With the exception of Bannockburn, Bruce looked to avoid ‘pitched battles’ at all costs. Even on his deathbed, Bruce is alleged to have reminded his son David II, never to fight a ‘pitched battle’ against the English. Despite Source C’s emphasis on castles, there are many other factors concerning Bruce’s military strategy and tactics that it fails to mention. Bruce employed a ‘scorched earth’ policy when Edward came north in 1310 with great success. By depriving the English force of the means to continue, they were consequently forced to retreat. Another key tactic, which deserves mention, was Bruce’s raids into northern England. These became especially numerous, after Bannockburn, when Bruce had achieved a level of internal control and looked to maintain his advantage over Edward II. While the motive for these raids was primarily economic, Colm McNamee is one of many historians to state their effectiveness. Bruce ensured that his raids into northern England coincided with internal problems in England. As part of the raids, Bruce would force the people of northern England to enter into truces, thus generating wealth for Scotland. One final point, Barbour forgets to comment on is that part of Bruce’s strategy and tactics came in the form of internal changes also. This is illustrated at the Scone parliament in 1318 where, it was decided that every man with goods that equated to the value of one cow should be armed with a weapon of some description. Alas, a farmer could no longer be expected to be tied to the soil all his life. Source C concentrates too much on one specific aspect of Bruce’s strategy and forgets to even touch on the various other and equally important factors, thereby rendering it only useful to a certain extent as evidence of Bruce’s strategy and tactics. 3. Source D is an extract from a ‘Summons’ to the Parliament of 1328. This primary source in itself echoes the important role that parliament had to play in the governing of Scotland under Robert I. The parliament of 1328 was held to finalise the peace settlement with Isabella and Mortimer who had recently usurped the English throne and were in no position to withstand more Bruce raids. Source D speaks of the various household offices that Bruce restored within parliament. Let us first examine the role of parliament under Robert I. Parliament was responsible for passing laws, ratifying treaties and supervising government finance. As well as this, parliament delved into matters relating to defence, justice and the overseeing of petitions presented to king and council. Robert Bruce instigated a policy of less royal control over local government. This built upon the de-centralised structure Scotland was beginning to take from 1298-1306. In March 1309 a parliament was held at St Andrews. This was at a time when the clergy was still refusing to acknowledge Robert Bruce as king. From a Bruce perspective, parliament was seen as a collective move against English interference. The organisation that holding parliament offered would be invaluable in governing Scotland effectively. In many respects, Source D is a symbol of the culmination of success that parliament had throughout Bruce’s reign. Consequently in 1310, parliament declared Robert Bruce as lawful king of Scotland. For Bruce, parliament was an instrumental tool for keeping order that could be used to maintain pressure on Edward II. Source D also mentions God, but fails to mention the definite place the Church had within parliament and in partnership with Bruce. This harks back to the ‘secret bond’ between Bruce and Bishop Lamberton in 1304. During 1306-1328 the Church was deeply worried about potential English interference in Scottish ecclesiastical affairs. One final point deserves a mention. In 1326, parliament offered a convenient place for Bruce to express his plea for taxation. Large grants to his trusted inner circle, (the two most prominent being Thomas Randolph and Sir James Douglas), had left Bruce in financial disarray. Overall, Source D gives a great first hand account of the role of parliament in 1328. However the source focuses solely on the situation in 1328 and does not reveal any information about previous parliaments and how they helped in the governing of Scotland.