Higher - Researching Physics - Planning an

advertisement

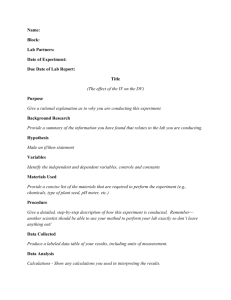

NATIONAL QUALIFICATIONS CURRICULUM SUPPORT Physics Researching Physics: Planning an Investigation Teacher’s Notes [HIGHER] The Scottish Qualifications Authority regularly reviews the arrangements for National Qualifications. Users of all NQ support materials, whether published by Learning and Teaching Scotland or others, are reminded that it is their responsibility to check that the support materials correspond to the requirements of the current arrangements. Acknowledgement Learning and Teaching Scotland gratefully acknowledges this contribution to the National Qualifications support programme for Physics. © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 This resource may be reproduced in whole or in part for educational purposes by educational establishments in Scotland provided that no profit accrues at any stage. 2 PLANNING AN INVESTIGATION (H, PHYSICS) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 Contents Introduction Variables Hypotheses 4 6 Lesson ideas: Variables Introduction: What is meant by variables? Suggested activity: Identifying variables (short introduction) Suggested activity: Indentifying different types of variables in an investigation Alternative suggestion: Inclusion of the above in other practical work 10 Lesson ideas: Hypotheses Suggested activity: Developing a hypothesis 11 PLANNING AN INVESTIGATION (H, PHYSICS) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 8 8 9 3 TEACHER’S NOTES Introduction Variables Whatever the constraints on teaching time, it is important that some lessons give students a degree of autonomy in practical investigations and allow them sufficient time to try different approaches. As well as motivating learning, open-ended practical investigations help them to appreciate the nature of scientific enquiry. Practical investigations can be a stimulating and interesting part of students’ science education and while it is beneficial i f they enjoy what they are doing it is more important that they learn through their experiences. Experimental work should never make students feel as if they are just carrying out a detailed set of instructions to find out something that they already know. The management of open-ended practical investigations can present challenges for the teacher. Students may have had different experiences of carrying out investigations, having come to Higher Physics by a variety of different routes. Different students in the same class may be carrying out different activities, perhaps as pairs or in small groups, and be at different stages within their investigations. A clear framework is needed to ensure that all students continue to work successfully and at a good pa ce throughout the allocated time. That is why it is essential that investigations are well planned, and that students have sufficient background knowledge and are fully aware of what is expected of them as well as knowing what they should have achieved by the end of the investigation. Having undertaken some web-based research, students need to revise or perhaps learn some of the vocabulary and concepts that they should have at their fingertips when planning an investigation by developing and testing a hypothesis. The first part of the work will concentrate on making sure that the students have a clear understanding of variables and the types of variable which feature in their investigation – the independent variable, the dependent variable and one or more controlled variables. At Higher it is useful that 4 PLANNING AN INVESTIGATION (H, PHYSICS) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 TEACHER’S NOTES students understand not only the concept of these variables, but also the vocabulary. In the design of experiments, an independent variable’s values are controlled or selected by the experimenter to determine its relationship to an observed phenomenon, which is the dependent variable. In such a n experiment, an attempt is made to find evidence that the values of the independent variable determine the values of the dependent variable. The independent variable can be changed as required, and it is not necessary to explain these changes, they are simply made by the investigator. The dependent variable, on the other hand, usually cannot be directly controlled and occurs as a direct consequence of varying the independent variable. One of the biggest challenges many people have to deal with when looking at an independent variable is the fact that all variables depend on something. While that may be true, there is an easy way to determine what this variable is. Simply ask the question: What do I need to change in order to influence, or try to influence, the other thing? The thing that needs changed is the independent variable. Controlled variables are also important to identify in investigations. They are the variables that are kept constant to prevent their influence on the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. Every experiment has a controlled variable, and it is necessary to not change it, or the results of the experiment won’t be valid. In summary Independent variables answer the question ‘What do I change?’ Dependent variables answer the question ‘What do I observe?’ Controlled variables answer the question ‘What do I keep the same?’ In addition to this it is useful to do some graph work to show which axis should be use for which variable. SQA marking stipulate s this. PLANNING AN INVESTIGATION (H, PHYSICS) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 5 TEACHER’S NOTES Hypotheses At this stage it is often useful to bring in the concept of the hypothesis. Often the introduction of the hypothesis will clarify the labels on the different types of variables when a student is having conceptual difficulties with the terms used. So why is a hypothesis needed? A good hypothesis will help the student to focus the investigation. It will keep them from ‘getting too involved in details’. As they progress through the investigation they might notice that more and more information comes out. The hypothesis will ensure that the investigation stays on course. A hypothesis is a tentative statement that proposes a possible explanation of what is happening in the investigation. A useful hypothesis is a testable statement, which usually includes a prediction. The student then goes on to test the prediction by altering one variable in a controlled manner and observing how it affects one other variable , with all the rest of the variables being kept constant. Sometimes a hypothesis is described a s an ‘if...then...statement’ but that is not really enough. In scientific research it is important that the hypothesis is reasonably formal such that a condition is described and then a conclusion is postulated, eg ‘If skin cancer is related to ultraviolet light, then people with a high exposure to ultraviolet light will have a higher incidence of skin cancer’ could be classed as a good hypothesis. A common problem is that students write a simple statement that is a cause and effect relationship that makes a prediction, eg ‘If I eat chocolate, then I will get pimples.’ They have to be reminded that what makes a hypothetical statement is the idea that two things might be, but not necessarily are, related. In other words the fail to state a proposed relationship before making the prediction. Literally speaking, cause and effect statements are often based on unstated assumptions. In models for scientific research, minimising assumptions first and then stating your hypothesis is how variables are controlled. A lo t of difficulties in writing hypotheses can be traced back to the simple lack of writing skill but students need to learn how to write in all subjects. Hypothesis writing is just one more contribution to overall literacy across the curriculum. It is unlikely that all students will reach this high level of success, so it will be necessary to make some judgements while assessing the work to decide whether or not a student has undertaken this aspect of the work to a reasonable standard, while ensuring that t he more able students have a good grasp of what would be ideal. Students need to be reminded frequently that a hypothesis is still valid even when results are the opposite of what is predicted because it will still shed light on the true nature of the relationship being tested. This lowers the risks of being wrong. For example, ‘If the period of a pendulum is related to its 6 PLANNING AN INVESTIGATION (H, PHYSICS) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 TEACHER’S NOTES length, then the longer the pendulum the shorter the period.’ Actually the results show just the opposite is true. Hypotheses that predict unrelated variables are also useful. For example, ‘If the period of a pendulum is related to its mass, then increasing the mass will increase the period. ’As it turns out, the mass has no effect at all, as the student will discover while testing this hypothesis. This is particularly important as students often make the assumption that since they are testing or investigating this, there must be a relationship and so massage the results accordingly. While it is important that this aspect of the cour se be looked at seriously, it is also important that there is not too much time spent here. It could be useful, but not necessary, if examples based on the investigations that the teacher is expecting the student to undertake were incorporated into these i ntroductory lessons. By the end of these lessons it would also be useful if the students have identified the dependent and independent variables that will feature in their own investigation as well as how the independent variable will be altered, how measurements will be taken and how the controlled variables will be kept constant. When the students fully understand what they are investigating and how they are doing this a hypothesis can be made before the practical work is undertaken. Finally These strategies could help to make open-ended investigations successful: Make clear at the start the minimum data set or equivalent required for all groups (eg ‘Three variables need to be investigated, with at least five sets of repeated results for each one’). Al so, make clear what written work needs to be produced. At the outset of a practical session, get each student (or student group) to agree a target with the teacher (eg ‘In this lesson we will collect at least 10 sets of results for mass against accelerat ion’). This could be done in advance of the session. Organise lessons so that there are allocated times for planning, practical work and writing up. Ideally, there should be at least one practical session after an initial writing-up session, so that students have an opportunity to repeat and check results, or to refine their method. This will help to encourage students to improve their results. PLANNING AN INVESTIGATION (H, PHYSICS) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 7 TEACHER’S NOTES Lesson ideas: Variables Introduction: What is meant by variables? The purpose of the introduction is to ensure that the students have a clear idea of what is meant by variables and are able to differentiate variables from non-variables. This may necessitate some adaptation of their previous assumptions and some maturity of thought. It is particularly important that students are aware that some variables, which have perhaps been referred to as being constant, are actually variables, which have a constant value within the boundaries of how the students have used them. Examples of this could be room temperature or g – the acceleration due to gravity. The second important issue is that students are able to decide which variables are relevant in any investigation that they are undertaking and which variables, although present, do not affect the investigation in any w ay; so are not relevant. An example of this is measuring speeds of an object travelling horizontally, which is not affected by the value of g. Suggested activity: Identifying variables (short introduction) Resources Sets of laminated cards with either a variable or a constant on each. Learning intention Students will understand what is meant by a variable and be able to differentiate it from a constant. The teacher can revise the idea of variables. Students should arrange these into two groups. This could be done individually, in twos or in groups, perhaps students working alone then sharing their findings with one another or in a group would work well but would need more resources. Ultimately, consensus should be reached on all the cards. Students will not have met many constants yet but should have met enough to make this a valid exercise and perhaps it might lead to further discussion. This activity can also be done using the interactive white board if there is one available. Students may be aware of the following constants: speed of light in a vacuum electronic charge mass of an alpha particle 8 PLANNING AN INVESTIGATION (H, PHYSICS) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 TEACHER’S NOTES mass of a proton mass of neutron Planck’s constant Avogadro’s number. Note: A much-simplified version of this lesson would be to identify variables , but care needs to be taken that students are aware that not everything that has a value is a variable. Physical constants can be found at: http://physics.nist.gov/cuu/Constants/index.html Suggested activity: Identifying different types of variables in an investigation Resources Set of laminated cards with a variable on each – optional. Set of laminated cards with investigation suggestions. These investigations will not be carried out. (An interactive white board is a possible option .) Learning intentions Students will be able to identify all the variables that have relevance in any investigation. Students will understand the terms independent variable, dependent variable and controlled variable, and will be able to identify each of these in any investigation. By careful questioning, the teacher will ascertain that the students understand the terms independent variable and dependent variable, and that there are always a few other variables in an investigation, which need to be kept constant. The teacher will also ascertain that the students can suggest ways of controlling those variables, which need to be controlled. If the teacher feels that it is required, students can work in pairs or in groups to discuss or clarify these ideas. If students are struggling with these concepts teachers may choose to work through one investigation idea with the students. Students are given investigation cards (or the information will be put on the whiteboard). These can be standard investigations from any level or previous course work, eg how does the speed of a trolley at the bottom of a slope depend on the angle of the slope? Students could work singly, in pairs or in groups to find all the variables involved in the investigation, using the laminated cards with the variables or simply writing them down in their PLANNING AN INVESTIGATION (H, PHYSICS) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 9 TEACHER’S NOTES lab book, and identify each different type of variable. It is useful for students to be given the opportunity to collaborate in some way to reinfo rce their learning. Several investigations could be analysed but it is more important to spend a bit more time analysing one or two investigations thoroughly than to skim over the surface of many investigations. Additional work could be undertaken at thi s stage to plan how these variables could be measured and how the controlled variables could be kept constant, which controlled variables are not easily controlled and what should be done in that case. As a final part of this work, the teacher may choose to introduce an actual investigation that the students will undertake, although this may be left until all the preparatory work is done. Alternative suggestion: Inclusion of the above in other practical work Suggested activity: Identifying different types of variables in an investigation Resources Any investigation or piece of practical work being undertaken by the student. Learning intention: Students will be able to identify all the variables that have relevance in any practical work they undertake. Students will understand the terms independent variable, dependent variable and controlled variable , and will be able to identify each of these in all their practical tasks. Instead of producing materials to concentrate solely on identifying variables, this can be done as an ongoing part of all the practical work that the students undertake. However, time should be set aside to ensure that the students have a full and clear understanding, and an ability to use all of the terms mentioned above. 10 PLANNING AN INVESTIGATION (H, PHYSICS) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 TEACHER’S NOTES Lesson ideas: Hypotheses Suggested activity: Developing a hypothesis Resources Set of laminated cards with investigation suggestions. These investigations will not usually be carried out. (An interactive white board is a possible option .) Learning intentions Students will be able to plan an investigation, identifying the independent and dependent variable, and suggest a possible relationship between them using an if...then...statement. Perhaps starting with a very simple, whole -class activity, eg the pendulum, a list of variables is identified. This could be done in many ways, eg think, pair, share. Think, pair, share Part 1 Each student identifies as many variables as possible and then shares their idea with a partner. After this a definitive is arrived at by any suitable method. From that decisions are made on which variables could be varied practically in the laboratory with the available equipment. The next step is to create the ‘if’ statement . For this example a statement would be ‘If the period of the pendulum depends on...’: the mass of the bob the length of the string the angle at which the swing starts. The ‘then’ statement follows: ‘As the mass increases, then the period will increase.’ At this point it is important that the full statement is sta ted. That the hypothesis is incorrect is not at all important. Part 2 Students could then do another one or more of these experiments in groups or later in pairs or individually, finally ending with their own investigation. PLANNING AN INVESTIGATION (H, PHYSICS) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 11