We are often asked about a methodology for resolving dilemmas

advertisement

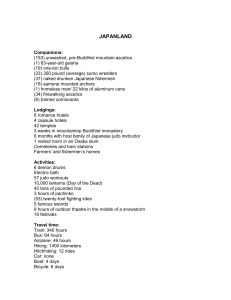

Conflict Resolution Across Cultures Fons Trompenaars and Charles Hampden-Turner Our societies have been characterized by a continuous series of conflicts. Often they have resulted in tremendous human tragedies ranging from intertribal wars in Africa to the Holocaust, Yugoslavia and recently the Iraqi war. Frequently the leaders of those devastating conflicts had only one principle in mind: “You are with us or you are against us”. In sharp contrast we have witnessed that all great things that have happened to humanity, from the invention of the wheel and penicillin to the founding of the United States of America and Internet were also the result of people or ideas in great conflict. However, here the leaders were essentially taking conflicting values as a source of energy from which they integrated conflicting values on a higher level and experienced a ‘whoosh’. Their main principle was rather: “I am against you, because you are my friend (and we have to protect you against wrong doing). If we observe the essence of Western civilization, and its political, educational and business logic in particular, it is too often striving on the logic of mutually exclusive values; you are with us or you are against us, you are centralized or decentralized, the Lexus or the Olive Tree, Individualist or Communitarian, McDonalds or the Jihad. Now, there is nothing against conflicting values of this sort. It is the way we are taught to deal with those tensions of opposing alternatives. They range from ‘it doesn’t matter as long as you make a choice’ to ‘we understand that values conflict, but once we need to work together to find a compromise’. This logic also reveals itself in the type of research we do and the instruments we use to get value differences mapped. Most of our questionnaires are designed to plot people on imaginary lines connecting opposite logics. They either look like Likert scales of strongly agreeing to strongly disagreeing. Or we use the fixed choice questionnaire of A versus B. You have to make a choice, so the values can be plotted on a scale. You are either an ‘individualist’ or a ‘communitarian’ person. A ‘Thinker’ or a ‘Feeler’, ‘global’ or ‘local’. In our consulting practice we have found that there is an alternative to this linear logic and it is called cybernetic logic. This logic stimulates people to think in dilemmas. This paradigm assumes that both conflicting values are worth striving for. Globalization is not worth less or more that Localization. Cutting cost or developing people are both values to strive for but on first glance they oppose each other. Dilemma logic not only assumes that values conflict but that they are reconcilable when synthesized. In this reconciliation process new values are created. This dialectical thinking about conflicting values has a very positive undertone. Any value that integrates its opposite leads to integrity. Or more negatively, any value that is disconnected from its opposite leads to a pathology. Individualism that cuts people from the group leads to egotism and the group that ignores the individual leads to communism. Both don’t work in the long run. The logic of dilemmas. Dilemma reconciliation could easily be described as good judgment, intuition, creative flair, vision and leadership. Yet all these capacities have proved elusive when people try to explain them and they tend to vanish as unexpectedly as they first appeared. A dilemma can be defined as: “two propositions in apparent conflict”. A dilemma describes a situation whereby one has to choose between two good or desirable options, e.g. ‘on the one hand we need flexibility’ whilst ‘on the other hand we also need consistency’. So, a dilemma describes the tension that is created due to conflicting demands. In dealing with such apparently conflicting propositions, you have several options: Ignoring the others. Abandon your standpoint. Compromise. Reconcile. One type of response is to ignore the other orientation. You are sticking to your own standpoint. Your style of decision making is to impose your own way of doing things either because it is your belief that your way of doing things and your values are best, or because you have rejected other ways of thinking or doing things because you have either not recognized them or have no respect for them. Another response is to abandon your orientation and “go native”. Here you adopt a “when in Rome, do as Romans do” approach. Acting or keeping up such pretences won't go unnoticed. Others may mistrust you - and you won't contribute your own strengths. Sometimes do it your way. Sometimes give in to the others. But this is a win-lose solution or even lose-lose solution. Compromise cannot lead to a solution in which both parties are satisfied - some thing has to give. What is needed is an approach where the two opposing views can come to fuse or blend - where the strength of one extreme is extended by considering and accommodating the other. This is reconciliation. At their simplest, values are seen as opposites, and we tend to see only the differences. However, one value cannot exist without the other. Errors need corrections for continuous improvement. Competing proves beneficial only when its results can be cooperatively harvested. Rules need exceptions for ever more enlightened legislation. Local, decentralized activities need to be thought about globally and centrally. We can now break the initial line into two axes and create a value continuum. “Value added” is probably a too narrow term, because only seldom do values add up like children’s wooden bricks placed on top of each other. Values come in all shapes and sizes and must be reconciled or integrated into larger meanings. Bridging these opposites in a creative way could be called an upward spiral. You could also describe it as innovative learning, or creating value. Managers succeed and prosper not by choosing one end over the other, but by reconciling both and achieving one value THROUGH its opposite. Two desirable aims are in creative tension; hence dilemmas must be reconciled into new integrities. How to resolve dilemmas We are often asked about a methodology for resolving dilemmas. It is a good and simple question. We wish that the answer was equally simple and that the results of our instruction equally good but, in truth, the more dilemmas you reconcile the more the process becomes intuitive rather than rational. The logic by which we reconcile becomes inaccessible, even to us. This is a very old problem. Try asking creative people how they create. You will be very disappointed with their answers. They are not being coy. They really do not know and cannot explain how their feats were achieved. The best we can do is to reconstruct the logic by which we approach dilemmas. If you follow the steps we propose, at least the barriers to seeing the solution will be removed one by one. The “steps” are all interconnected and are merely a means to an end. So leap to your conclusion as soon as it occurs to you. The steps are just prompts to help you see. If one step helps you more than others then go with that one. This paper looks in detail at one specific situation. We will deal with a famous international dispute between Australia and Japan. THE AUSTRALIAN–JAPANESE SUGAR NEGOTIATIONS In the late 70s a famous misunderstanding between Australian sugar cane growers and Japanese sugar refiners occurred. It rum-bled on for years. Both parties were indignant and perplexed at the other’s “bad behavior”, as they saw it. The Japanese refiners had signed a ten-year, long-term contract to buy Australian sugar at the then market price, less $5. The Australians would get the security of a ten-year sales agreement. The Japanese would get guaranteed supplies at a competitive price vis-à-vis other refiners. Everyone seemed happy and the deal was signed. Hardly was the ink dry on the paper then the price of sugar on world markets crashed by $10 a ton. The Japanese refiners faced the prospect of paying more for their raw sugar than anyone else, a cost that would fatally impact on the price of refined sugar and every-thing made from it. Up to this point, both cultures probably saw eye-to-eye. It had been a good deal but now circumstances had changed and the Japanese refiners faced genuine difficulties. The cultural split occurred over what to do about this. The Japanese suggested to the Australians that the contract be renegotiated. After all the Australians could not possibly wish their partners to lose money; mutual satisfaction and lasting relationships were surely the ideal. The Australians pointed out that a contract was a contract. The Japanese had given their word. Fluctuations in the world price of sugar were not unusual. All business involved risks. Had the price risen, not fallen, the Australian growers would have been the losers. You cannot go crying to your partner every time markets shift. If we want to reconcile this conflict we first have to examine the value differences at stake. If these are not formulated correctly the conflict cannot be solved and the cultures cannot cooperate. What is dividing these cultures is the following value orientations Contract versus Relationship Letter of the law versus Spirit of the law Rule versus Exception It will help us to see possible solutions if we compare these dilemmas (or bifurcations) to at least four of the seven dimensions, outlined in Riding the Waves of Culture (1997). A theme running through the dispute above is whether a universal rule applies or particular circumstances make the rule of the contract unjust and inappropriate. This was dimension 1, Universalism versus Particularism. A second dimension associated with this conflict is Individualism versus Communitarianism. Is each individual partner responsible for his/her own profitability and fortune or do they share one fate as a community? A third dimension involved in this particular conflict is Specificity versus Diffusion. The letter of the law and the small print in the contract is specific, while the spirit of the law and the goodwill associated with mutual relationships are both diffuse. Finally, there is even a touch of Achieved versus Ascribed status. The Australians say that you “achieve what you bargain for, no more and no less.” The Japanese say that the ascription of being a business partner should override what each achieves from their bargain. It should come as no surprise that Australians are overwhelmingly Universalist, Individualist, Specific, and Achievement oriented, while the Japanese are much more Particularist, Communitarian, Diffuse, and Ascriptive of status. This was a conflict waiting to happen. If there is a universal obligation for individuals to honor the specific letter of the law, then the Australians are right. If there is a particular reason to form a better community and respond to the diffuse spirit of the law, in exceptional circumstances, then the Japanese are right. Mapping Our first step is to map this dilemma. Instead of putting the conflict at opposite ends of a rope, and just pulling back and forth, we can create a dual axis “map”, see Figure 8.1. Three things need to be noted about this map. First, by creating a dual axis, we have made for a “culture space” where various outcomes can be compared. Second, the labels on both axes are “good.” We have expressed what the Australians sincerely believe on the vertical axis and what the Japanese sincerely believe on the horizontal axis. Thirdly, we have shown that each value can be maximized at the other’s expense at 10/1 and 1/10, compromised at 5/5, or synergized at 10/10. Reconciliation involves synergy. Strategy and making epithets Step two is to stretch each principle as far as it will go, noting the good and bad points of doing this. If we take “sanctity of contract” to its logical conclusion, then this has clarity, legal sanction, freedom of contract – but also rigidity, inflexibility, and closure. If we take a “special and exceptional relationship” to its logical conclusion, we get subtlety, flexibility, harmony, but also ambiguity, relativism, and broken promises. 10 10/10 1/10 Culture Space The letter of the Universal law of the contract 5/5 10/1 0 The spirit of the ongoing exceptional relationship Figure 1 Dual axis map 10 It helps to create epithets, or short explicit statement about extreme positions, that might typically used in the rhetorical exchanges between Australians and Japanese when they are arguing. Hence the Australians might call the Japanese “slippery customers” and the Japanese might call the Australians “tablets of stone inscribed.” An epithet can also be used for the middle 5/5 position to remind ourselves that cutting our principles in half is not what we want. Let us call this “half way to meet the bastards.” Our map now looks like Figure 2. 10 10/10 Reconciliation ? 1/10 Tablets of Stone Inscribed The letter of the Universal law of contrast 0 5/5 Half Way to Meet the Bastards 10/1 Slippery customers 10 Figure 2 Dual axis map, step 2 Note that 1/10, 5/5, and 10/1 are on a straight line. We have not yet escaped from our tug of war. However, we have made fun of our own extreme positions and we have admitted to some downsides of taking our values to extremes. If you can laugh together over absurd extremes there is less chance of crying later on. If you can admit that your own position can be satirized, not just that of your opponent, then this is a step forward. Five steps to reconciliation These are as follows: • Processing • Framing and contextualizing • Sequencing • Waving/Cycling • Synergizing Let’s go through these one by one and see if they throw up any ideas about reconciliation. If such ideas occur to you, then forget the remaining steps. As we’ve noted, they are just stepping stones enabling you to cross from one reality to another. Processing One assumption we have continually challenged is that values are things. “The sanctity of contract” conjures up the image of a legal document, which specifies exactly what we must do. The special relationship is another potential idol, inviting worship. Aristotle told us that two opposite things could not occupy the same space and ever since then we have been running away from the specter of contradiction. But if values are processes not things, then we have left the world of solid objects and entered the “frequency realm,” the world of waves, vibrations, frequencies, spectra, and fields. Instead of “rock logic,” we have “water logic,” to use Edward de Bono’s terms. The easiest way to convert values from things to processes is to add “ing” at the end. Hence, not contract but contracting, not law but legislating or drafting, not exceptions but making exceptions, not relationship but relating. Does this make any difference? Yes, quite a lot. Relating and contracting do not sound very polarized at all. Nor do ruling and finding exceptions. If logic is like ripples of water why should not these form elegant and aesthetic patterns? Framing and contextualizing All values and communications are a text within a context or, if you prefer, a picture within a frame. Values remain integral so long as the text is not separated from the context, or the picture from its frame, nor the figure from its ground. The simplest context is two levels of abstraction: To create a contract We are relating So as to clarify our relationship We are contracting The higher level is the context. The concrete process is the text. The utility of a picture and a frame is to show that one value sur-rounds or embraces the other. So as to render the We are making exceptions contract more resilient So that our relationship We are legislating is clear to both partners What the crash in the world price of sugar has done is to tear the text from the context and the picture from the frame. Any reconciliation is going to have to put these together again. Sequencing Dilemmas look worse than they are when they confront us simultaneously in traumatic situations: “To be or not to be, that is the question.” We cannot honor a contract and break a contract at the same time, but we could do both in a sequence. We could honor the existing contract, but negotiate an additional one, compensating the Japanese in some degree for their likely losses on the first contract. We are contracting, before making exceptions, before recontracting. Alternatively, we could take Japanese “exceptionalzing” seriously and redraft the contract to give them a $5 reduction per ton on raw sugar below the existing market price, whatever that price might be. This would bring the volatility of markets into the contract terms. You could specify that a 5 percent reduction or rise in world prices would trigger an automatic renegotiation but that a lesser volatility would not. Indeed, here the crisis looks more and more like an opportunity to improve both contracting and relating – and at the end of this process there will be a much better agreement. Waving/cycling A waveform is, of course, a rolling cycle. It is a short step from creating a sequence to turning this into a learning loop. With rules everyone can live with… In highly exceptional circumstances Will lead to a far superior contracting process The Japanese are right; improving relationships between partners is the name of the game. Between both parties, you can generate more and more value. But the Australians are also right that these relationships, however subtle, need to be codified into legally binding reciprocal obligations. The rule of law is indispensable. What these laws have to do is cover more and more particulars. Exceptions are there to test good laws and who does not want to be in some way exceptional? Good legislation leaves room for this. It puts freedom within the law (as picture and frame). Synergizing Synergy, we may recall, means to “work together”. We must improve our relating so that we can improve our contracting. We must continue finding exceptions so that our later agreements cover more eventualities. We know that synergy is present as we move towards 10/10 on our original map, so that both ‘contract law’ and ‘exceptional relationships’ optimize each other. Now it is not easy to draft a contract that anticipates many contingencies and leaves both parties with discretion to meet unforeseeable problems, but it is possible and laws that enshrine our freedoms are on the statute books. It was Brandeis, the great American jurist, who said that the US Constitution was a charter for learning. On a much more modest scale, that is what a new contract between Australian growers and Japanese refiners has to be. The reconciled dilemma looks like Figure 8.3. Note that our cycle has turned into a helix that winds its way upwards achieving better relations through better contracting and better contracting through better relating. At top left the evolving relationships have been brilliantly codified. If all this sounds grandiose let us consider in detail the reconciliations of the quarrel between Japanese refiners and Australian growers. Among our suggestions would be these: For the Australian growers: Ask that the existing contract be honored and in exchange draft a new contract that secures further business but helps to ameliorate the refiners’ current losses. This contract should offer a $5 concession on the world price of sugar, whether it rises or it falls. For the Japanese refiners: Ask to renegotiate the contract but pledge to honor it without alteration for a specified time period, unless the fluctuating price falls outside a $10 band, in which case negotiating starts again. Make sure the new contract incorporates all aspects of the ongoing relationship that can be codified, while protecting areas of discretion for both parties. Make the new contract a celebration of the rapport, which you have already achieved and the even better mutuality to which you aspire. 10 10/10 Evolving relationships brilliantly codified 1/10 Tablets of Stone Inscribed Legislating contracting ruling 5/5 Half Way to Meet the Bastards 10/1 Slippery customer 0 Relating, particularising and finding exceptions 10 Figure 3. Helical reconciliation Why Dilemmas? From Data to Information, Meaning and Knowledge There are two worlds, each as real as the other. There is the world of facts, of atoms, in which we give statistical expression to hard data. These consist of exclusive categorisiations, either-or, this or that, yielding thousands of annotated objects. Then there is another world, reflective of our languages, a world of information or difference, with no necessary connection to visible objects. These are differences of value, aim, feeling, opinion, perception; a world of contrasts, which are binary. As we increasingly drown in more and more of our own data, we urgently need an alternative logic to generate meaning and knowledge. This kind of information has typically two ends, equally vital to our development and survival. Errors need corrections if continuous improvement is to occur. Results need to be framed by questions if knowledge is to accumulate. Differences need to be integrated. Competing needs to have its results shared cooperatively if learning is to occur. Rules need exceptions forever more enlightened legislation. Local, decentralised activities need to be thought about globally and centrally if strategies are to improve. We improve and prosper not by choosing one end over the other, but reconciling the values at both ends and achieving one value THROUGH its opposite. Two desirable aims are in creative tension, hence "dilemmas", pairs of propositions, must be reconciled. In our dangerous world of polarising differences, wherein hatreds have grown murderous, we must bridge new chasms, if these are not to engulf us. We call these skills of reconciling contrasting values, transcultural competence, although it includes differences not necessarily rooted in the cultures of nation states. Indeed the integration of values into ever-larger systems of satisfaction is a new definition of what it means to create wealth. In our consulting practice we have found that even in cases where reconciliation was not achieved, people came out of the experience with a satisfied feeling. In many cases participants to the reconciliation process refer to the fact that it is so satisfying to have an alibi to discuss the pro’s and con’s of each of the opposite positions without being pushed away. By formalizing the process of dialogue all parties involved get ample opportunity to clarify their position. Even in cases where there is no answer to the essential reconciling question: ”How can value X help you to increase the quality of value Y?”, one is dialoging around the possibility for resolution of the conflict. We have distinguished seven steps that help participants to go from conflict to resolution: 1. Identify the dilemma and its holder 2. Chart the dilemma 3. Stretch the dilemma: - List pro’s & con’s of each proposition 4. Define epithets (= stigmatizing labels) 5. Reconcile the dilemma 6. Identify obstacles 7. Design an action & implementation plan - team and individual action plan - identify the behaviors required to support the planned action With the process of identifying and charting both parties can exaggerate the pro’s and con’s of each position. The epithets give an opportunity to publish stereotypes, but for both parties, inviting them not to go for the pathology of disconnected values that oppose each other or compromise between them. Conclusion Too much of our attention as multi-cultural practitioners and scholars is focused on explaining differences. These differences are consciously or unconsciously plotted on linear scales setting the stage for participants to either take an extreme position or to go for a compromise. Our role should become one of facilitating the process of dialogue within a cybernetic logic, the logic of dilemma recognition, respect and reconciliation.