roberta challenges her staff[1]

advertisement

![roberta challenges her staff[1]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007538369_2-997e43842721977303cfe6733b330368-768x994.png)

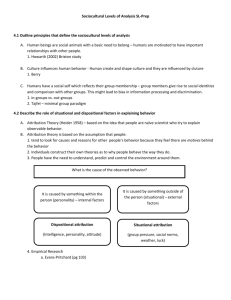

CHAPTER 7 SOCIAL PERCEPTION AND ATTRIBUTIONS CHAPTER SUMMARY Perception is a cognitive process that allows us to interpret and understand our surroundings. Social cognition is the study of how people perceive one another. The four-stage sequence presented in Figure 7-1 presents a basic social information processing model. The four stages include: selective attention/comprehension, encoding and simplification, storage and retention, and retrieval and response. Since we do not have the mental capacity to fully comprehend all of the stimuli within the environment, we selectively perceive portions of environmental stimuli. Attention is the process of becoming consciously aware of something or someone. We tend to pay attention to salient stimuli. Encoding and simplification involves interpreting or translating raw information into mental representations. These mental representations are then assigned to cognitive categories. Categories are defined as a group of objects that are considered equivalent. As part of the categorization process, people, events and objects are compared with schemata. A schema represents a person’s mental picture or summary of a particular event or type of stimulus. The third phase involves storage of information in long-term memory. Longterm memory consists of separate but connected categories. The final stage requires drawing on, interpreting, and integrating categorical information to form judgments and decisions. This social information process has profound managerial implications. Person perception is susceptible to several errors including halo, leniency, central tendency, recency effects, and contract effects (see Table 7-2). Person perception also is prone to the formation of stereotypes. A stereotype is an individual’s set of beliefs about the characteristics or attributes of a group. Stereotypes may or may not be accurate and are not always negative. Different kinds of stereotypes include sex-role, age, race, and disability stereotypes. People’s expectations or beliefs determine their behavior and performance through the self-fulfilling prophecy, and thus serve to make their expectations come true. Figure 7-2 presents a model of the selffulfilling prophecy showing how supervisory expectations affect subordinate performance. First, high supervisory expectancy produces better leadership, leading employees to develop higher selfexpectations. Higher expectations motivate employees to exert greater effort, ultimately increasing performance and supervisory expectancies. Finally, successful performance also improves an employee’s self-expectancy for achievement. Managers must harness the potential of the self-fulfilling prophecy by building a hierarchical framework that reinforces positive performance expectations. Attribution theory holds that people attempt to infer causes for both our own and others’ observed behavior. Kelley’s model of attribution is based on the premise that behavior can be attributed to either internal factors within a person (e.g., ability) or to external factors within the environment (e.g., task difficulty). To make attributions, we gather information along three behavioral dimensions: consensus, distinctiveness, and consistency. Consensus involves a comparison of an individual’s behavior with that of his or her peers. Distinctiveness is determined by comparing a person’s behavior on one task with his or her behavior on other tasks. Consistency is decided by judging if the individual’s performance on a given task is consistent over time. According to Kelley, people attribute behavior to external causes when they perceive high consensus, high distinctiveness, and low consistency. Internal attributions are made when the observed behavior has low consensus, low distinctiveness, and high consistency. The fundamental attribution bias reflects one’s tendency to attribute another person’s behavior to his or her personal characteristics rather than to situational factors. The self-serving bias represents one’s tendency to take greater personal responsibility for success than for failure. Social Perceptions and Attributions These findings have important implications for managers. Managers tend to disproportionately attribute behavior to internal causes, which may result in inaccurate performance evaluations, and thus reduce employee motivation. Also, since managers’ responses to employee performance vary according to their attributions, attributional biases may lead to inappropriate managerial actions. Finally, an employee’s attributions for his or her own performance have dramatic effects on subsequent motivation, performance, and personal attitudes such as self-esteem. 75 Chapter 7 LECTURE OUTLINE I. An Information Processing Model of Perception (PPT Slides: 4-5, Self-Exercise: Does a Schema Improve the Comprehension of Written Material?, and Group Exercise: Win, Lose or Schema apply here) A. Four-Stage Sequence and a Working Example 1. The fours stages of social information processing are: selective attention/comprehension, encoding and simplification, storage and retention, and retrieval and response. . B. Stage 1: Selective Attention/Comprehension (Ethical Dilemma: Should Brain Scans be Used to Craft Advertising applies here). II. 1. People are continuously bombarded by physical and social stimuli in the environment. Since they are unable to fully comprehend all this information, they selectively attend to subsets of environmental stimuli that include salient or important information. C. Stage 2: Encoding and Simplification 1. Before information is stored, it must be interpreted or translated into mental representations. Perceivers assign pieces of information to cognitive categories. People, events, and objects are interpreted and categorized by comparing their characteristics with schemata. D. Stage 3: Storage and Retention 1. Long-term memory consists of separate but connected categories containing different types of information. Information also passes among the categories. E. Stage 4: Retrieval and Response 1. Ultimately, judgments and decisions are the product of drawing on, interpreting, and integrating categorical information stored in long-term memory. F. Managerial implications 1. Inaccurate impressions regarding the fit between the applicant and the job requirements lead to poor hiring decisions, inaccurate performance appraisals, distorted evaluations of leaders, distorted communication, aggressive and antisocial behavior, and negatively affects employee well-being. Stereotypes: Perceptions about Groups of People (PPT Slides: 7-12, Supplemental PPT Slides: 31, 3340, Self-Exercise: How Do Diversity Assumptions Influence Team Member Interactions?, and Group Exercise: Do Stereotypes Unconsciously Influence the Perception Process? apply here) Table 7-2 describes five common perceptual errors including halo, leniency, central tendency, recency effects, and contrast effects. A. Stereotype Formation and Maintenance 1. Stereotypes can lead to poor decisions, create barriers for women, older individuals, people of color, and those with disabilities, and can undermine job satisfaction. 2. Stereotyping is a four-step process. First, people are categorized into groups according to various criteria, such as gender, age, race, and occupation. Next, we infer that all people within a particular category possess the same traits or characteristics and then we form expectations of others and interpret their behavior according to our stereotypes. Finally, we maintain our stereotypes. B. Sex-Role Stereotypes 1. Research indicates than men and women do not systematically differ in the manner suggested by traditional stereotypes, yet the stereotypes persist. C. Age Stereotypes 76 Social Perceptions and Attributions III. 1. Age stereotypes depict older employees as less satisfied, involved, and motivated. Research suggests that these stereotypes are not accurate. D. Racial and Ethnic Stereotypes 1. One study found that black and white managers did not differentially evaluate their employees based on race, but research also suggests a same-race bias for Hispanics and blacks in the interview process. E. Disability Stereotypes 1. 62% of the disabled are unemployed and make less money than those without disabilities. F. Managerial Challenges and Recommendations 1. Organizations need to educate themselves about the problem of stereotyping. 2. Organizations must reduce stereotypes throughout the organization. This can be done by increasing the amount of quality contact among members of different groups. 3. Managers should identify valid individual differences that differentiate between successful and unsuccessful performers and use these criteria. 4. Managers should remove promotional barriers for men and women, for people of color, and those with disabilities. Self-Fulfilling Prophecy: The Pygmalion Effect (PPT Slides: 13-15 and Supplemental PPT Slides: 28-29 apply here) IV. A. Research and an Explanatory Model 1. Raising instructors' and managers' expectations for individuals can produce higher levels of achievement and productivity. 2. The self-fulfilling prophecy works in both positive and negative directions. B. Putting the Self-Fulfilling Prophecy to Work 1. Managers need to harness the Pygmalion effect by building a hierarchical framework that reinforces positive performance expectations throughout the organization. 2. Managers can create positive performance expectations when they recognize the potential to increase performance, instill confidence, set high performance goals, positively reinforce employees, provide constructive feedback, help employees advance through the organization, introduce new employees as if they have outstanding potential, become aware of personal prejudices, encourage employees to visualize successful task completion, and help subordinates master key skills and tasks. Causal Attributions (PPT Slides: 16-25 and Group Exercise: Using Attribution Theory to Resolve Performance Problems apply here) A. Kelley's Model of Attribution 1. Behavior can be attributed either to internal factors within a person (e.g., ability) or to external factors within the environment (e.g., task difficulty). 2. People make causal attributions after gathering information on three dimensions of behavior: consensus, distinctiveness, and consistency. a. Consensus involves a comparison on an individual's behavior with that of peers. b. Distinctiveness is determined by comparing a person's behavior on one task with his or her behavior on other tasks. c. Consistency is determined by judging if the individual's performance on a given task is reliable over time. 77 Chapter 7 B. Attributional Tendencies 1. The fundamental attribution bias causes perceivers to ignore relevant environmental forces which may significantly influence behavior. 2. The self-serving bias makes it difficult to accurately assess personal responsibility for mistakes. C. Managerial Application and Implications 1. Managers tend to disproportionately attribute behavior to internal causes, leading to inaccurate performance evaluations and reduced employee motivation. 2. Managers' attributional biases may lead to inappropriate managerial actions, including promotions, transfers, or layoffs. 3. An employee's attributions for his or her own performance have important effects on subsequent motivation, performance, and personal attitudes. 78 Social Perceptions and Attributions OPENING CASE SOLUTION 1. Why do people from China and the United States have different perceptions of the same events? Explain. Different perspectives between two such different cultures can stem from a variety of sources including education, history, and language. Complicating matters are the sometimes distorted perspectives that each culture may have of the other. OB IN ACTION CASE SOLUTION 1. Would you go under the knife to enhance your career opportunities? Why or why not? This is a personal opinion question. 2. What negative stereotypes are fueling the use of cosmetic surgery to change one’s appearance? Age stereotypes begin by categorizing an individual into a group based on his or her age. Next, the stereotype holder infers that all people within that age group possess the same traits or characteristics. Based on these beliefs, the stereotype holder forms expectations about the stereotyped group and interprets the behavior of all group members according to stereotypic beliefs. Finally, the holder perpetuates his or her stereotype by overestimating the frequency of stereotypic behaviors exhibited by group members, incorrectly explaining observed behaviors, and mentally differentiating those forty-something and over from himself or herself. Age stereotypes typically portray older workers as less satisfied, not as involved with their work, less motivation, not as committed, less productive, more apt to be absent from work, and more accident prone. Executives are certainly aware of these stereotypes. “They believe that looking older in business now means looking vulnerable, not wise and experienced.” The vast majority survey respondents, mostly in their 40s and 50s, “thought age had cost them a shot at a particular job.” According to Rick Miners, “ageism is unfortunate but it exists, and if you aren’t looking good, you aren’t a player.” 3. To what extent does the Pygmalion effect, Galatea effect, and Golem effect play a role in this case? Explain. According to the self-fulfilling prophecy, or Pygmalion effect, people's high expectations or beliefs determine their behavior and performance, thus serving to make their expectations come true. The Golem effect is a loss in performance resulting from low leader expectations. We strive to validate our perceptions of reality, no matter how accurate or inaccurate those perceptions may be. Figure 7-2 presents a model of the self-fulfilling prophecy. It’s important to remember that the self-fulfilling prophecy works in both positive (Pygmalion) and negative (Golem) directions. The Galetea effect occurs when an individual’s high self-expectations for himself or herself lead to high performance. The anonymous 56-year-old public-relations manager who had his lower eyelids done feels that “his new look has given him more confidence at work, prompting him to volunteer for new projects.” This man’s experiences demonstrate the Galetea effect. When being 40 or 50 “means looking vulnerable,” it’s quite likely that other’s lower expectations also lead to the Golem effect. 4. Based on this case and what you learned in this chapter, do the skills that come with age and experience count for less than appearance in today’s organization? Discuss your rationale. This is a personal opinion question, but the executives mentioned in the case certainly feel that the skills that come with age and experience count for less than appearance in today’s workforce. In one survey, 82% rated age bias a serious problem. Additionally, 94% of respondents (mostly in their 40s & 50s) said they thought age had cost them a shot at a particular job. 79 Chapter 7 INSTRUCTIONAL RESOURCES 1. 2. 3. 4. See “Do Stereotypes Unconsciously Influence the Perception Process?” and “Win, Lose or Schema” by A. Johnson & A. Kinicki in An Instructor’s Guide to an Active Classroom, 2006, McGraw-Hill/Irwin. Age stereotypes are discussed in The Aging Work Force, (Washington D.C.: American Association of Retired Persons Work Force Programs Department). See “Gender, Age, and the MBA: An Analysis of Extrinsic and Intrinsic Career Benefits” by R. Simpson, J. Sturges, A. Woods, & Y. Altman in Journal of Management Education, 2005, 29(2), pp. 218-247. All sides of the Pygmalion effect are covered in W. Rowe and J. O’Brien, “The Role of Golem, Pygmalion, and Galatea Effects on Opportunistic Behavior in the Classroom” Journal of Management Education, December 2002, Vol. 26 No. 6, pp. 612-628. TOPICAL RESOURCES 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. A great chat on perceptual biases can be found in “The Actor-Observer Asymmetry in Attribution: A (Surprising) Meta-Analysis” by: B. Malle in Psychological Bulletin, 2006, 132, pp 895-919. See “Penalties for Success: Reactions to Women Who Succeed at Male Gender-Typed Tasks” in Journal of Applied Psychology, 2004, 89(3), pp. 416-427. See “Using SAT – Grade and Ability – Job Performance Relationships to Test Predictions Derived From Stereotype Threat Theory” by M. Cullen, C. Hardison, & P. Sackett in Journal of Applied Psychology, 2004, 89(2), pp. 220-230. See “The Effect of Physical Height on Workplace Success and Income: Preliminary Test of A Theoretical Model” by T. Judge & D. Cable in Journal of Applied Psychology, 2004, 89(3), pp. 428-441. An interesting discussion of attribution and bias in a very modern work context can be found in “Misattribution in Virtual Groups: The Effects of Member Distribution on Self-Serving Bias and Partner Blame” by: J. Walther and N. Bazarova in Human Communication Research, 2007, 33, pp. 1-26. VIDEO RESOURCES McGraw-Hill Supplements: 1. The Organizational Behavior Video DVD, Volume One contains the following videos that correspond with this chapter content: Gender Pay Gap and Wal-Mart Faces Discrimination Lawsuit. Suggested teaching notes and discussion questions are located in the Video Cases and in a separate PowerPoint file containing all Videos on the book’s website at www.mhhe.com/kreitner. Additional Video Resources: 1. The damaging influence of negative expectations is explored in the film "Case of the Missing Person" (CRM Films). 80 Social Perceptions and Attributions 2. 3. 4. The managerial implications of attributional tendencies are clarified in the film, "Managing Motivation," (Salenger Educational Media). The impact of the perceptual process is the subject of the film, "Perception," (McGraw-Hill Films). The power of the self-fulfilling prophecy is examined in the film "Productivity and the SelfFulfilling Prophecy: The Pygmalion Effect" and its sequel "The Galatea Effect: Managing the Power of Expectations," (CRM Films). DISCUSSION QUESTIONS 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Describe your schema of a typical college professor. Apply the four-stage social information processing model to the purchase of a new car. Describe a situation in which you were guilty of making a fundamental attribution bias or selfserving bias. Apply attribution bias and self-serving bias to an important situation in your life. How might your instructor utilize the self-fulfilling prophecy to increase student test scores? 81 Chapter 7 SUPPLEMENTAL EXERCISE 1: PAUL’S NEW JOB APPLICATION The mini-case presented below may be used to illustrate concepts of Kelley’s model of attribution. It describes a situation in which a new hire, Paul, exhibits behavior which demonstrates low consensus (he doesn’t act sociable and friendly as others do), low distinctiveness (he behaves the same way in a variety of situations), and high consistency (he behaved in this manner over a three month period). There is also evidence of a self-fulfilling prophecy. Paul’s coworkers now believe he is unfriendly, and thus behave in unfriendly ways toward him. He then withdraws even more, confirming their original impression. Discussion questions follow the mini-case. *** Paul Johnson just returned from his probationary performance review, which is given 90 days after initial employment. While he got generally favorable marks from his boss, Sam, he was disappointed to be marked low in “teamwork and working with others.” Sam told him he seemed aloof. His coworkers complained that he was unfriendly and not a “team player.” When Paul first came to work at the company, he was overwhelmed by how much there was to learn. He thought the best way to go about learning it all was to work hard and stay focused. He went straight to his work station every day without stopping for coffee and chit-chat with his coworkers, even though he was invited more than once. He brought his lunch from home so he could keep learning about his new job over the lunch hour. He was pleasantly surprised at how social everyone was at lunch time, but he thought it was more important to learn rapidly and work hard in order to make a good impression. He also tried hard to learn the names of all the people he worked with, but ended up knowing only a few after three months time. To disguise the fact that he didn’t know people’s names, he would look down when he passed someone in the hall. His feelings of being “out of the loop” were especially pronounced during staff meetings when everyone else was full of ideas, comments, and humorous remarks. It was hard for Paul to understand everything people were talking about because he just didn’t have the background that others did. He remained quiet during staff meetings so that he wouldn’t say anything foolish that might draw attention to himself. After about two months on the job, he realized that his attention to his work was paying off and that he had learned most of what he needed in order to perform well. He started stopping by in the lounge in the mornings for coffee and asked some of his coworkers to go to lunch with him. He was disappointed at the negative responses he received. People tended to ignore him in the mornings and not accept his lunch invitations. When he made a comment at the next staff meeting, a coworker said “Well, what do you know, it speaks.” Everyone laughed at the joke and ignored his contribution. At this point, Paul is honestly confused about what has gone wrong and how he ended up with low marks for teamwork. He is beginning to wonder if he has a future at this company. 1. Using Kelley’s model of attribution, explain how Paul ended up with a low rating for “teamwork and working with others.” 2. Is there a self-fulfilling prophesy at work here? Explain. 3. What can or should Paul do now if he wants to change his image at this organization? 82 Social Perceptions and Attributions SUPPLEMENTAL EXERCISE 2: ROBERTA CHALLENGES HER STAFF1 APPLICATION This is the second installment of the continuing Roberta case. Students should preferably read “Introduction to Roberta” from Chapter 1 to provide background information. Other installments may be used in conjunction with each other or independently. In this installment, Roberta’s staff has become trapped in a self-fulfilling prophecy. Roberta works to break through their self-set perceptual barriers. This installment may also be used to demonstrate motivational issues. Students may discuss the case questions after reading the case, or you may prefer to use it as a written assignment. Discussion questions are provided at relevant points throughout the case. *** Roberta was pleased with the changes her department had made in the past three months. Complaints about the old "Complaint Department," now renamed the Customer Service Department, were down to a trickle. Although there was still some "holdout" behavior from a few members of the group, overall they were working well together. The department was starting to develop a team attitude. As Roberta walked down the hall to her boss's office, she reviewed the successes of the past months. Her positive thoughts were echoed by Sam Moore as she entered his office. "Roberta, I am very pleased with the progress your department has made. Complaints from our customers have stopped almost entirely, and I hear good comments about the customer service department from our internal people on a regular basis." "Thanks Sam," responded Roberta. "I have to give a lot of the credit to my team. They really have begun to pull together." "The main reason I called you in today, Roberta, is to discuss the effect our purchase of Medium Conglomerate, Inc. will have on your department. Since M.C. Inc. has no customer service department, you won't have to worry about integration like some of the other departments. However, we expect this merger to increase sales by 30 percent over last year. What I need is an estimate of the personnel and cost increases required to keep your department operating at its current level of performance. We have plenty of time on this. I'll need the information by late next month, when the merger is completed." "I will be able to get you that information easily by then," Roberta stated. "I may need to speak with the manager of sales at M.C. Inc. to get more information on the type of product packages they work with and their customer base." "That will be no problem. I will get you his name and phone number. By the way, I found an article in this month's copy of Industry News that I think might be helpful to you. It looks at customer service departments of five companies in our industry who are rated tops in customer satisfaction. There are some productivity measures listed. It might be interesting to compare their figures with ours." "Thanks Sam," said Roberta, "I'll take a look at this." 1 Originally developed and written by Maria Muto, Arizona State University. Cooperatively revised by Maria Muto, Arizona State University, and Edwin C. Leonard, Jr., Indiana-Purdue University at Fort Wayne. 83 Chapter 7 When Roberta got back to her office, she pulled last month's progress report and compared their productivity figures to the published data. She was surprised to discover that her department, even with all the improvements, had a productivity level that averaged 60 percent of the ones listed. With Sam Moore's request for the cost and personnel increases needed to absorb a higher work load, this article was particularly timely. Maybe her department could increase efficiencies instead of costs. She decided to bring this up at Monday's staff meeting. Monday morning, Roberta walked into the meeting armed with copies of the monthly productivity totals set next to the averages provided in the article. After explaining the situation, she asked for input. "I don't understand," Jenny exclaimed, "You said you wanted the customer to get lots of attention, and now you're telling us we spend too much time with them. You can't have both." "I agree," said Bill, the veteran of the office. "It's impossible to complete any billing exchange in less than two hours. No one can go any faster than we do and do a truly good job." Dolores, one of the best performers in the department responded, "You know, Roberta, we're pleased with the changes in the department since you came. I'm willing to try whatever you suggest to improve productivity, but I really don't see what else we can do to go faster." "I'm going to do some research on the techniques these other departments are using," answered Roberta. "All I want is your guarantee to try out new ideas and see how they work." "We'll try them," said Jenny, "But I still don't believe that we can save any more time." 1. What common perceptual problem did Roberta uncover in her staff meeting? Explain. 2. What steps could Roberta take to begin to turn around her group's self-perception? Roberta knew that her first job was to convince her department that they were capable of improving their performance. To break through their static perceptions of how much they could accomplish, Roberta decided to use a variation on a Total Quality Management technique, benchmarking. Through contacts with a local professional association, and from her old school friends, she knew people at three of the five companies mentioned in the article. Since their product lines were non-competitive, Roberta was able to arrange for one of her employees to spend a day at each of the three departments. For the visits, she choose three staff members who were receptive to new ideas, and who had some influence over the team. Their instructions were to look for new, more efficient ways of doing things. In addition, on the days when they were gone, Roberta filled in, discovering several short-cuts and demonstrating them to the staff at their next meeting. Each staff member who visited one of the other three companies came back and made a presentation of the ideas and techniques that could work in their department. Each possibility was discussed, and some were implemented. As a result, the weekly performance reports began showing a steady rise in productivity. Roberta knew she had broken through a barrier when Bill remarked one day, "I guess you were right Roberta, there's always room for improvement." Roberta had some ideas for continuing to improve the productivity of her department, but she needed Sam Moore's support. She walked into his office one day prepared to lay out a detailed plan for absorbing the workload created by the merger with Medium Conglomerate, Inc. 84 Social Perceptions and Attributions "Sam, as you know, we will have to absorb a 35 percent sales increase over the next 8 months due to the gradual consolidation with M.C. Inc. Under my department's past productivity levels, I would need seven more customer service representatives in order to maintain comparable performance with the sales increases. This is based on an estimate that each of our customer service representatives currently manages 5 percent of our sales concerns. However, I believe that there is an alternative. I would like to improve productivity in my department to absorb the increase without increasing staff. This would move our department productivity levels to within 10%of the norm in our industry for firms with higher performance and customer satisfaction standards." "Sounds good," said Sam. "That would be a significant cost savings for the company. But I am concerned. A 35% increase in productivity is ambitious for any department." "I know the goal will be a stiff challenge," Roberta replied. "But based on my research and the information provided through some benchmarking we've done, I think it's achievable. Over the past month, we have already reached a 10% productivity increase, and my people are using the extra time to explore other time-saving options. I have set a schedule for improvement, and every staff member will get a copy of their own and the department's productivity levels on a weekly basis. With tangible, measurable goals and the ideas for improving productivity, I think this will work. The main concern I have is keeping my group motivated to reach that goal, and that's where I need your help." "What do you want me to do?" Sam asked. "Well, because of the problems with this department in the past, merit raises were rare and turnover high. Consequently, most of my staff are close to the bottom of their pay scales. I want the company to invest some of the money saved from the productivity improvements back into my staff. With your support, I would like to offer them the opportunity to get some of that cost savings in their paychecks. The amount should be significant for them, so I was thinking of $500 a year or more per person for every 5% increase in productivity. This pay raise would be in addition to their standard raises at the end of the year. It would be something special. Doing this will still cost HRI less than half the salary cost of adding the new staff, not considering the facilities and benefits expenses. I also believe that this vote of confidence and support will make a big difference on every aspect of my staff's selfperceptions and performance. "I like the idea," said Sam after a few minutes of thought. "It is daring but I think you may be able to make it work. I'll OK it on one condition: that you keep detailed notes on this project so we can use it as a pilot study for productivity improvement in other departments." "I will be happy to do that," Roberta replied. "I am glad you accepted the idea. Before I go, I do have one other request. I do not expect to be included in the $500 raise aspect of this, but if I succeed in absorbing the entire 35% sales increase.... "Shall we say a $10,000 raise for you, as additional motivation?" replied Sam, smiling. "That sounds fair," answered Roberta. 3. Provide some practical suggestions for tactics that could help Roberta challenge her staff to improve their productivity. Feel free to draw upon the motivational and goal-setting concepts presented in Chapters 7 and 8. 85 Chapter 7 SUPPLEMENTAL LECTURETTE 1: WEINER’S MODEL OF ATTRIBUTION APPLIED TO GENDER DIFFERENCES IN MANAGERIAL EXPECTATIONS 1 APPLICATION This lecturette introduces another popular attribution model – of Weiner’s model of attribution. Gender differences in causal attributions for success and failure are discussed. *** Bernard Weiner, a noted motivation theorist, developed an attribution model to explain achievement behavior and to predict subsequent changes in motivation and performance. Weiner believes that the attribution process begins after an individual performs as task. A person’s performance leads him or her to judge whether it was successful or unsuccessful. This evaluation then produces a causal analysis to determine if the performance was due to internal or external factors. Weiner proposes that attributions vary along two dimensions: locus (the extent to which a cause is internal to the individual or something in the environment) and stability (the extent to which the cause remains stable over time across similar tasks). (Weiner also discusses a third dimension – controllability – but the other two factors have received the majority of the research attention.) Ability and effort are the primary internal causes of performance and task difficulty, luck, and help from others the key external causes. The two primary dimensions yield four causes of performance. Ability is internal and more stable, effort is internal but less stable, luck is external and less stable, and task difficulty is external and stable. These attributions for success and failure then influence how individuals feel about themselves. For example, a metaanalysis of 104 studies involving almost 15,000 individuals found that people who attributed failure to their lack of ability (as opposed to bad luck) experienced psychological depression. The exact opposite attributions (to good luck rather than to high ability) tended to trigger depression in people experiencing positive events.2 In short, perceived bad luck took the sting out of a negative outcome, but perceived good luck reduced the joy associated with success. Note that the psychological consequences can either increase or decrease depending on the causes of performance. For example, student self-esteem is likely to increase after receiving an “A” on an exam if he or she believes that performance was due to ability or effort. In contrast, the same grade can either increase or decrease self-esteem if the student believes that the test was easy. Finally, the feelings that people have about their past performance influences future performance. Future performance is higher when individuals attribute success to internal causes and lower when failure is attributed to external factors. Future performance is more uncertain when individuals attribute either their success or failure to external causes. In further support of Weiner’s model, a study of 130 male salespeople in the United Kingdom revealed that positive, internal attributions for success were associated with higher sales and performance ratings. 3 A second study examined the attributional process of 126 employees who were permanently displaced by a plant closing. Consistent with the model, as the explanation for job loss was attributed to internal and 1 Adapted from P. Rosenthal, D. Guest, and R. Peccei, “Gender Differences in Managers’ Causal Explanations for Their Work Performance: A Study in Two Organizations” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 1996, Vol. 69 No. 2, pp. 145-151; L. Larwood and M. Wood, “Training Women for Management: Changing Priorities” Journal of Management Development, Vol. 14 No. 2, pp. 54-64. 2 See P. Sweeney, K. Anderson, and S. Bailey, “Attributional Style in Depression: A Meta-Analytic Review” in Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, May 1986, pp. 974-991. 3 See “P. Corr & J. Gray, “Attributional Style as a Personality Factor in Insurance Sales Performance in the UK” in Journal of Occupational Psychology, March 1996, pp. 83-87. 86 Social Perceptions and Attributions stable causes, life satisfaction, self-esteem, and expectations for reemployment diminished.1 Furthermore, research also shows that when individuals attribute their success to internal rather than external factors, they have higher expectations for future success, report a greater desire for achievement, and set higher performance goals.2 Women still face unequal career progression in management compared to men. Weiner’s attribution model provides one potential explanation for this state of affairs. Laboratory studies have found differences when men and women provide explanations for identical levels of their own performance. Women tend to attribute the cause of their success less to ability than do men, and be more likely to believe that their failures result from a lack of ability. If this finding generalizes to an organizational setting, it could help explain the unequal career progression of men and women. Women may be less likely to perform the types of self-promoting career development necessary to advance. Rosenthal, Guest, and Peccei tested this idea in an organizational setting. They surveyed junior- and middle-level managers in two organizations: a hospital and the head office of a financial services firm. Managers were asked to discuss two examples of their behavior – one representing successful and the other unsuccessful performance. Then they were asked to make attributions for each outcome. Attributions were assessed by asking managers to rate the extent to which four key factors had contributed to the performance outcome. For successful performance, the factors were (1) your personal skills and abilities, (2) the hard work and effort you invested in the task, (3) the positive circumstances in which you found yourself, and (4) the relative ease of the task at hand. In the case of unsuccessful performance, the factors were (1) deficiencies in your personal skills and abilities, (2) the lack of effort you invested in the task, (3) the negative circumstances in which you found yourself, and (4) the relative difficulty of the task at hand. Results indicated no gender differences in managers’ explanations for unsuccessful performance. However, female managers attributed their successful performance significantly less to ability than did male managers. Further anecdotal evidence is also disturbing. A survey of men and women executives found that women do not expect to be as financially successful as men. Men expected to be rewarded for their work, and are indignant and vocal when they are overlooked. Women hope to be recognized, but they don’t demand or feel entitled. Finally, women want to be chosen for key training and assignments, but men tend to be more assertive and initiate requests for special development. If women managers are more hesitant to attribute their successes to high ability, they may be setting a self-fulfilling prophecy in motion. Their attributions may constrain expectancies for future success and in turn affect motivation to succeed, leading to less successful behaviors. 1 See G. Prussia, A. Kinicki & J. Bracker, “Psychological and Behavioral Consequences of Job Loss: A Covariance Structure Analysis Using Weiner’s (1985) Attribution Model” in Journal of Applied Psychology, June 1993, pp. 38294. 2 See B. Weiner, An Attributional Theory of Motivation and Emotion (New York: Springer-Verlag, 1985). 87 Chapter 7 SUPPLEMENTAL LECTURETTE 2: SHIFTING STANDARDS AND STEREOTYPE ACCURACY 1 APPLICATION This lecturette may be used to expand on the chapter’s coverage of stereotype formation and maintenance. *** One rationale used to explain the use of stereotypes in social cognition is the shifting standards model. Briefly, this model suggests that when stereotype holders make judgments about others on stereotyperelevant issues, they do so by calling to mind a within-group standard of comparison. For example, male targets are judged relative to a male standard while female targets are judged according to a female standard. This model assumes that the use of stereotypes involves perceived between-group differences, and that the perceiver shifts or alters his or her standards of judgment depending on the target’s social category. The use of different standards of comparison may mean that the labels applied to targets from different social groups are not directly comparable. A commonly held sex-role stereotype might include greater aggressiveness on the part of men than women. When making judgments regarding how aggressive an individual man or women is, the perceivers’ standards are likely to shift according to this expectation. A woman’s aggressive behavior is more inclined to be perceived as such because this behavior is more likely to surpass the perceiver’s expectations for the typical aggressiveness of women than of men. This may be the case even if the aggressive woman’s behavior is less objectively aggressive than the aggressive man’s. Thus, the label “very aggressive” when applied to a woman communicates a different meaning than when it is applied to a man. Is there a way to avoid the inconsistency caused by the use of shifting standards and come to a common conclusion? Yes, by using a more objective, externally anchored rule of judgment (e.g.. 5’9” rather than ‘average height’). The disadvantage, of course, is that objective standards are not readily available in many instances in which we make judgments. The use of (shifting) subjective standards may serve to hide the operation of stereotypes, while objective scales (which don’t shift) may reveal the existence of stereotypes. That is, subjective standards may mask the extent to which we are guided by our stereotypes. Indeed, a number of studies support this conclusion. As an example, one study asked participants to read a short article attributed to either a female (Joan) or male (John) author. The article focused on either a masculine (e.g., bass fishing), feminine (e.g., cooking) or gender-neutral topic. Readers judged the monetary worth of the article in either objective (e.g., if you were the editor, how many dollars would you pay the author?) or subjective (e.g., ‘very little money’ to ‘lots of money’) terms. As expected, in the objective judgment condition, feminine articles were viewed more positively when written by Joan than by John (i.e., Joan was paid significantly more money than John). Masculine articles were judged more positively when written by John than by Joan. Readers in the subjective judgment condition did not differentially judge male and female authors by topic. How might the shifting standards phenomenon appear in real-world judgments? Take the case of an employer who ascribes to traditional gender stereotypes (e.g., males are more capable than females) 1 Adapted from M. Biernat “The Shifting Standards Model: Implications of Stereotype Accuracy for Social Judgment” in Stereotype Accuracy: Toward Appreciating Group Differences, 1995 Lee, Jussim & McCauley eds., American Psychological Association: Washington DC, pp. 87-114; M. Biernat and M. Manis “Shifting Standards and Stereotype-Based Judgments” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1994, Vol. 66 No. 1, pp. 5-20. 88 Social Perceptions and Attributions faced with a hiring decision involving two objectively equal job applicants, one male and one female. Will the employer be affected by his pro-male bias and thus hire the male? Or will he evoke shifting standards and be impressed that this individual woman has surpassed his (relatively low) expectations for female competence and hire her? As often is the case in organizational behavior, the answer must be “it depends.” One factor which may influence the outcome is the attribution made for the women’s competence. An ability attribution might sway the decision in the woman’s favor. Research along this line is continuing to explore factors such as credibility of the perceiver and knowledge of the perceiver’s standards. 89