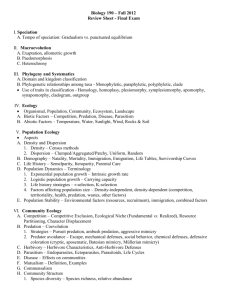

Nonconscious Mimicry - Center for Behavioral Decision Research

advertisement