Sophocles is considered one of the great ancient Greek tragedians

advertisement

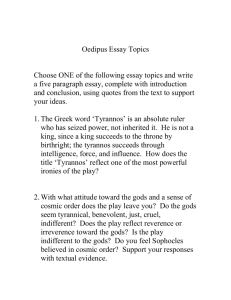

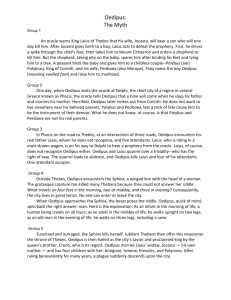

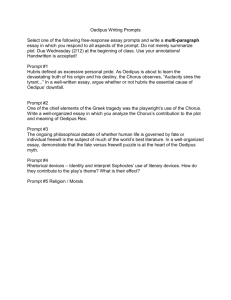

The Oedipus Cycle Sophocles is considered one of the great ancient Greek tragedians. Among Sophocles' most famous plays are Oedipus the King, Oedipus at Colonus, and Antigone. These plays follow the fall of the great king, Oedipus, and later the tragedies that his children suffer. The Oedipus plays have had a wide-reaching influence and are particularly notable for inspiring Sigmund Freud’s theory of the "Oedipus Complex," which describes a stage of psychological development in which a child sees their father as an adversarial competitor for his or her mother’s attention and affection. The three plays are often called a trilogy, but this is technically incorrect. They weren't written to be performed together. In fact they weren't even written in order. Antigone, which comes last chronologically, was the play Sophocles wrote first, around 440 B.C. It wasn't until about 430 B.C that Sophocles produced his masterpiece Oedipus the King. He finally wrote Oedipus at Colonus in 401 B.C., near the end of his life. Also note that the plays were rarely if ever revived during the playwright's life time, so it's not like it would have been easy for Sophocles' audiences to compare them. What’s the BIG DEAL? Well….. Stop us if you've heard this one before: guy walks into a bar, meets Han Solo, hits on a girl who turns out to be his sister, steps up to save a galaxy, and finds out by the end of the second movie that his greatest enemy is *gasp* his father! Well, it's a familiar tale, not just for all moviegoers post1977 – but also for all theatergoers after, say, 429 B.C. Take out that bit about Han Solo (and also, maybe the bar), and change sister to mother and you've got the bare bones of Sophocles's Oedipus the King: guy gets chosen as the One to battle evil (sadly, not a host of stormtroopers; Sophocles goes with a plague caused by the evil presence of a murderer in Thebes), hits on and eventually marries his mother, and finds out that he himself was his father's killer without even knowing it. Our point is: it seems kind of bizarre to us now to believe absolutely in fate. But all of Sophocles's characters believe in it, to the point where the father of this truly dysfunctional family (King Laius) is willing to order his infant son (Oedipus) killed when a prophecy tells him that his son will be his murderer. And all of the father's efforts to prevent his own death don't work. Why? Because it's fate: these characters have no real control over their own lives. Just like it's fate that Luke meets Leia and then Darth Vader. The neat thing about fate in both Oedipus the King and Star Wars works is that, really, these guys don't have any control over their own lives – because they're fictional. After all, what kind of character development would there be if Darth Vader was defeated without knowing he was Luke's father? Would Darth Vader ever have **spoiler alert** been redeemed at the end? The relationship has to come out, or else there'd be no narrative after the first movie. Oedipus marries his mother by accident, and if they were allowed to just hang around staying married and living in blissful ignorance, what would Sophocles be telling his audience? Nothing anyone would want to hear outside of Jerry Springer. So fate comes in to make sure we learn a lesson: marrying your mother and killing your father is so wrong that it will bring plague to your city and make you tear your own eyes out in horror. And in a way, maybe all fiction is about fate, even today: after all, fictional characters can’t avoid what their authors lay out for them. How It All Goes Down Oedipus Rex (or Oedipus the King) King Oedipus, aware that a terrible curse has befallen Thebes, sends his brother-in-law, Creon, to seek the advice of the Greek god Apollo. Creon informs Oedipus that the curse will be lifted if the murderer of Laius, the former king, is found and prosecuted. Laius was murdered many years ago at a crossroads. Oedipus dedicates himself to the discovery and prosecution of Laius’s murderer. Oedipus subjects a series of unwilling citizens to questioning, including a blind prophet. Teiresias, the blind prophet, informs Oedipus that Oedipus himself killed Laius. This news really bothers Oedipus, but his wife Jocasta tells him not to believe in prophets—they've been wrong before. As an example, she tells Oedipus about how she and King Laius had a son who was prophesied to kill Laius and marry her. Well, she and Laius had the child killed, so obviously that prophecy didn't come true, right? Jocasta's story doesn't comfort Oedipus. As a child, an old man told Oedipus that he was adopted, and that he would eventually kill his biological father and sleep with his biological mother. Not to mention, Oedipus once killed a man at a crossroads, which sounds a lot like the way Laius died. Jocasta urges Oedipus not to look into the past any further, but he stubbornly ignores her. Oedipus goes on to question a messenger and a shepherd, both of whom have information about how Oedipus was abandoned as an infant and adopted by a new family. In a moment of insight, Jocasta realizes that she is Oedipus’s mother and that Laius was his father. Horrified at what has happened, she kills herself. Shortly thereafter, Oedipus, too, realizes that he was Laius’s murder and that he’s been married to (and having children with) his mother. In horror and despair, he gouges his eyes out and is exiled from Thebes. Oedipus at Colonus After years of wandering in exile from Thebes, Oedipus arrives in a grove outside Athens. Blind and frail, he walks with the help of his daughter Antigone. Neither she nor Oedipus knows the place where they have come to rest, but they have heard they are on the outskirts of Athens, and the grove in which they sit bears the marks of holy ground. A citizen of Colonus approaches and insists that the ground is forbidden to mortals and that Oedipus and Antigone must leave. Oedipus inquires which gods preside over the grove and learns that the reigning gods are the Eumenides, or the goddesses of fate. In response to this news, Oedipus claims that he must not move, and he sends the citizen to fetch Theseus, the king of Athens and its environs. Oedipus then tells Antigone that, earlier in his life, when Apollo’s oracle prophesied his doom, the god declared that Oedipus would die on this ground. The Chorus enters, cursing the strangers who would dare set foot on the holy ground of Colonus. The Chorus convinces Antigone and Oedipus to move to an outcropping of rock at the side of the grove, and then interrogates Oedipus about his origins. When Oedipus reluctantly identifies himself, the Chorus cries out in horror, begging Oedipus to leave Colonus at once. Oedipus argues that he was not responsible for his horrible acts, and says that the city may benefit greatly if it does not drive him away. Oedipus expresses his arguments with such force that the Chorus fills with awe and agrees to await Theseus’s pronouncement on the matter. The next person to enter the grove is not Theseus but Ismene, Oedipus’s second daughter. Oedipus and the two girls embrace. Oedipus thanks Ismene for having journeyed to gather news from the oracles, while her sister has stayed with him as his guide. Ismene bears terrible news: back in their home of Thebes, Eteocles, the younger son of Oedipus, has overthrown Polynices, his elder son. Polynices now amasses troops in Argos for an attack upon his brother and Creon, who is ruling along with Eteocles. The oracle has predicted that Oedipus’s burial place will bring good fortune to the city in which it is located. Both sons, as well as Creon, know of this prophecy, and Creon is currently en route to Colonus to try to take Oedipus into custody and thus claim the right to bury him in his kingdom. Oedipus swears he will never give his support to either of his sons, for they did nothing to prevent his exile years ago. The Chorus tells Oedipus that he must appease the spirits whom he offended when he trespassed on the sacred ground, and Ismene says that she will go and perform the requisite libation and prayer. Please define the following terms in the context of ancient Greek Drama: CHORUS: CHORAGOS: PROLOGUE: PARADOS: ODE: SCENE: PEAN: EXODOS: