How to Use Existing Literature: A Guide to Literature Searches

advertisement

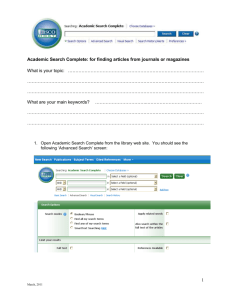

How To Use Existing Literature This chapter addresses the following topics: Conducting a Comprehensive Literature Search Reviewing Literature Literature Search The term “literature search” is pretty self-explanatory, as it refers to the process of searching for previously written literature that relates to a topic. As a general rule, it is best to begin with an exhaustive literature search. Even if it takes a lot more time, this provides you the benefits of a complete understanding and broad knowledge base of the research field, as well as the option to eliminate references as you narrow your research topic. It is better to eliminate irrelevant sources than to attempt to stretch just a few into an entire structure of support and explanation for the research you have or will conduct. There are several ways to search for literature related to a specific topic. Here are three of the most common: Citation Searching is looking for any and all literature that references a particular author or publication. Searching for literature that cites a source you are using lets you know where that particular research led others. This is one way of finding out about current research in a particular area. Forward Citation Searching is the tracking down of references cited by relevant sources. This means you get to find, and be familiar with, the literature that led to the sources you’re basing your own hypothesis and methodology on. This type of search is sometimes referred to as the “ancestry approach” or footnote chasing. Keyword Searching is probably the most common search type, and often is the easiest to feel comfortable doing. This involves specifying words that an electronic database will search for to generate a list of sources that utilize them. Most topics are referenced in several different ways, and a professional Search thesaurus is a great way to find alternate search terms. The Thesaurus of Psychological Index Terms is an example of a professional search thesaurus. There a lot of resources available for performing lit searches, some of which are easily accessible from ETSU. This university provides us with free access to many journals and other professional publications through online indexes and the main campus library. There are also a few Internet sites (http://www.findarticles.com, for instance) that allow access to a limited number of journals free of charge. A Step-by-Step Strategy Step 1: Key Search Terms Key search terms (sometimes called keywords) are the words or phrases used to identify all articles that might be relevant to our project. These are different words that mean the same thing, and words/phrases that come out of a professional thesaurus. Sometimes, as we search, we will find that several articles list a common keyword that we have not been searching for. We should add these keywords to our search lists. Most of the time, I will provide the initial list of key search terms. Step 2: Searching Online Databases Within each appropriate online database, a search should be performed for each of the keywords on the search list. For some broader terms, it will be necessary to pair it with a couple different terms to generate more concise source lists. Here is a list of online databases provided by ETSU EMBASE Psychiatry ERIC Mental Measurements Yearbook PsycINFO PsychCrawler Criminal Justice Abstracts JSTOR InfoTrac Expanded Academic Sociological Abstracts PsychWeb Step 3: Compiling Lists of Possible Sources Each time you search for a keyword in a database, it will list all the articles in the database that relate to that keyword. Some databases have the option to convert these lists into bibliographic/reference style citations. Copy and paste the citation information into a word document or excel file to help stay organized. Each time you perform another search, you can add to your list, sort alphabetically, get rid of any duplicates, and make notes about the ones that you have already figured out you don’t need. This takes some time, but is completely worth it. This will help you stay organized and wards off danger of searching out the same article twice. Step 4: Collection of Abstracts As you compile your list of sources, seek out electronic copies of the abstracts. If the only way to read the abstract is by viewing the first page of the article, go ahead and download it. That way you won’t have to search for it again. If you decide not to use it, only a couple keystrokes are required to delete the file. Step 5: Elimination of Irrelevant Literature As you gather abstracts, sort through them to eliminate the articles that you definitely will not need. The articles remaining on the list will be the ones we need to track down. Step 6: Collection of Articles This step is both simple and time-consuming. Use the list produced by step 5 to gather sources. Some of these you can get online, and some you will have to go to the library to retrieve. When you print articles, tell the printer to print two pages per sheet. This is almost always large enough to read, and it keeps expenses down. Whenever you are able to access an article or other reference via the computer, save it on your computer. Then you have the option of reading it whenever you want, and only print it off if you think it is relevant to your project. When you save a web page, specify “Web Page, HTML only” in the “Save As Type” field of the “Save As” dialog box. Saving copies will also ensure that you never have to track down a source more than once. Step 7: Citation Search for Authors Refer to the section on types of literature searches to find out what a citation search is. At this time, ETSU does not provide access to a database that will perform specifically this function. However, if you visit UT’s library to copy articles, check out this search option. Step 8: Compile List of Cited Sources For each article you collect that you decide is relevant, compile a list of their references. Often, previous researchers have already found the best sources out there. If you decide an article isn’t quite right, but a few references in its intro section do seem to fit your topic, add just those few articles to your list of articles to find, and at least browse their abstracts. Step 9: Repeat Steps 4-8 Unfortunately, this step is exactly what it sounds like. This process is a great big circle, and sometimes you must travel it many times for a single project. Literature Review Although inconvenient, there is no way around the fact that not every article you collect will be relevant to your study. If every article you find is directly related to your hypothesis, you probably should seriously consider revising it. As you review articles, there are a few key sections you should check out. First, read the abstract because this often helps eliminate unrelated research. If you think an abstract relates to an element of your hypothesis, go ahead and read the author’s hypothesis and method. The hypotheses are usually included in one of the last paragraphs of the introduction, and are sometimes referred to as objectives. Scan the results section for specific statistics you are interested in, and look over the limitations and implications sections of the discussion. For most articles, this will provide you with a solid base knowledge of the experiment. If you don’t understand part of what took place in a study described in an article, read more of it until you do. If you read the entire article and still can’t figure out what the author was attempting to do, ask for help. The more familiar with journal literature a person becomes, the easier it is for them to understand the language and terms used in articles. Active reading is also an important part of evaluating articles. This step is not solely for making a decision about the relevance of an article to your research. This is also the appropriate time to identify questions about why parts of an experiment were conducted a particular way, or why certain variables were not included. This is a task of critical thinking. As many experienced researchers will tell you, one of the easiest things you can do to save yourself time is to only read an article once. The only way to do this, however, is to take notes as you read. Anything you read that might be relevant to your research should be written down, along with any citations that go with it, and an abbreviated citation of the source you are getting the information from. This information can be organized in several ways. For some researchers, it is easier to just list this information, phrasing it in their own words for later use. Personally, I use index cards for this step. On the back of each index card, I include a shortened reference, usually just the last name of the first author, the year it was published, and a word or two of the title. On the front of the cards, I include excerpts from the paper that I think will be relevant to my research project. I write these down exactly as they appear, and put them in quotation marks on my index cards. The reason I do not paraphrase is that, sometimes, if you paraphrase something now, it may have less meaning later. Researchers usually choose their words very carefully; a particular phrasing might not be as relevant to you at first as it will be when you are more familiar with the literature. Another good reason to write down article excerpts verbatim is for greater cohesion when you write the paper. The more articles you read through, the better understanding you will have of the purpose and style used in scientific writing. This is what you want to emulate in your own writing. Not only does saving the “re-phrasing” for later mean that you will be better prepared to write in this professional, scientific style, but it also will help to ensure that your paper flows and the topic unfolds seamlessly.