Punctuation Update

advertisement

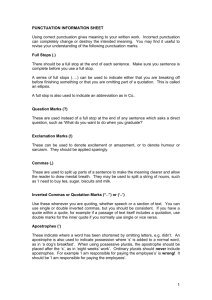

Johnson, English 101-021 Fall 2007 Punctuation: A Guide to Making Good Choices The purpose of punctuation is to make writing accessible and clear. A skilled writer uses punctuation to create emphasis, connections, analysis, contrast, definition, explanation, summary, and many other techniques. Punctuation should not draw attention to itself; so, improper punctuation does just that—distracts the reader from the content and, otherwise, stylistic craft of your writing. This conference and handout is by no means exhaustive or prescriptive: revise it and break away from it as you become more comfortable and able to justify your punctuation decisions. Let’s talk about the denotative meaning (one that you’d find in a dictionary or grammar book) of punctuation marks: Periods The period signals a full stop. Use periods at the end of a sentence. (Put periods at the end of a complete sentence enclosed by parentheses.) Put a period outside parentheses if what is enclosed by parentheses is not a complete sentence (like this). Also, “A period also goes inside quotation marks.” However, a question mark or exclamation point goes outside the quotation marks unless the mark is part of the quotation. Semicolons The semicolon is perhaps the most feared punctuation mark; however, the rules for semicolons are simple. Use a semicolon to link two independent clauses, meaning complete syntactical expressions. The two clauses are complete sentences by themselves, but they are connected by a thought. You can also use semicolons like a comma, in order to separate items on a list, especially if the listed items contain commas; replace prepositions, like yet, however, therefore, and many others; and to take risks and use a different type of punctuation. Colons A colon usually means as follows. Colons can sometimes act like a dictator. Colons can perform many tasks: create emphasis, list items, and illustrate important ideas. Pay attention to the items following a colon. (And try to sit up straight as you do this.) Dashes Dashes are sort of like a fancy comma or parentheses. Dashes separate an aside from the rest of the sentence—similar to this example—and add a dramatic flair or an element of sophistication to your writing (most of the time). The clause inside the dashes can be thought of as being whispered to you. Commas The comma helps readers understand the rhythm of the sentence, separating and emphasizing complex sentences with combined clauses and statements. The comma slows the reader down, inserts a natural pause, and adds clarity. The copious uses for commas show the complexity and versatility of this little curvaceous mark: Use commas to separate two independent clauses connected by and, but, or, nor, and for. Use commas to separate items in a list. Use commas to separate dependent clauses, like this one, from the rest of the sentence. As your writing progresses, use commas to offset introductory phrases. Don’t offset a defining clause—one that can’t be left out of sentence—with a comma. For example: Bananas that are green, taste tart is incorrect, since “taste tart” cannot be eliminated from the sentence, which contrasts with this independent clause that could be eliminated without changing the entire meaning of the sentence. This independent clause that could be eliminated without changing the entire meaning of the sentence could simply be a new sentence. Interruptions, however rude or unnecessary, should be offset by commas. Use commas to set off an appositive, a noun or pronoun that explains or introduces the noun that precedes it. But what does this all mean? Punctuation rules can seem rigid and structural; however, I encourage you to try using punctuation marks in different ways adds variety and spice to your writing. For example, John Dawkins constructed the Ideas for this conference and handout borrowed/taken from Devan Cook, Barry Lane, Andrea Lunsford, Harry Noden, and the Staff of The Princeton Review. Johnson, English 101-021 Fall 2007 Punctuation Hierarchy, which demonstrates the different ways to punctuate. His Hierarchy offers different options for punctuating the same sentence: Dawkin’s Punctuation Hierarchy (1987) Maximum Separation (the period, the question mark, and the exclamation mark) Example: I looked up. And there she stood. Medium Separation, Emphatic (the dash) Example: I looked up—and there she stood. Medium Separation, Anticipatory (the colon) Example: I looked up: And there she stood. Medium Separation (the semicolon) Example: I looked up; and there she stood. Minimum Separation (the comma) Example: I looked up, and there she stood. Zero Separation Example: I looked up and there she stood. Note how the various marks slightly alter the meaning of the sentence. The period illustrates a dramatic stop, whereas no punctuation creates a rushed, hurried, and more fluid version. Experimenting and trying out different ways to use punctuation is a great way to decipher which methods you prefer and fit your style of writing. Published authors try new variations and combinations all the time; that’s what makes writing such an interesting process, as our perceptions and decisions about grammar change and flow with the language. Let’s try a short exercise in punctuation. Read this passage from Moby-Dick (1851) by Herman Melville, add punctuation (including a few capitalizations of words at the beginning of sentence, as I conveniently left those out), and think about how your choice of punctuation marks adds to the comprehension and readability of the writing: Call me Ishmael some years ago never mind how long precisely having little or no money in my purse and nothing in particular to interest me on shore I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world it is a way I have of driving off the spleen and regulating the circulation whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth whenever it is a damp drizzly November in my soul whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street and methodically knocking people’s hats off then I account it high time to get to the sea as soon as I can Ideas for this conference and handout borrowed/taken from Devan Cook, Barry Lane, Andrea Lunsford, Harry Noden, and the Staff of The Princeton Review.