Review - GraceMessenger.com

advertisement

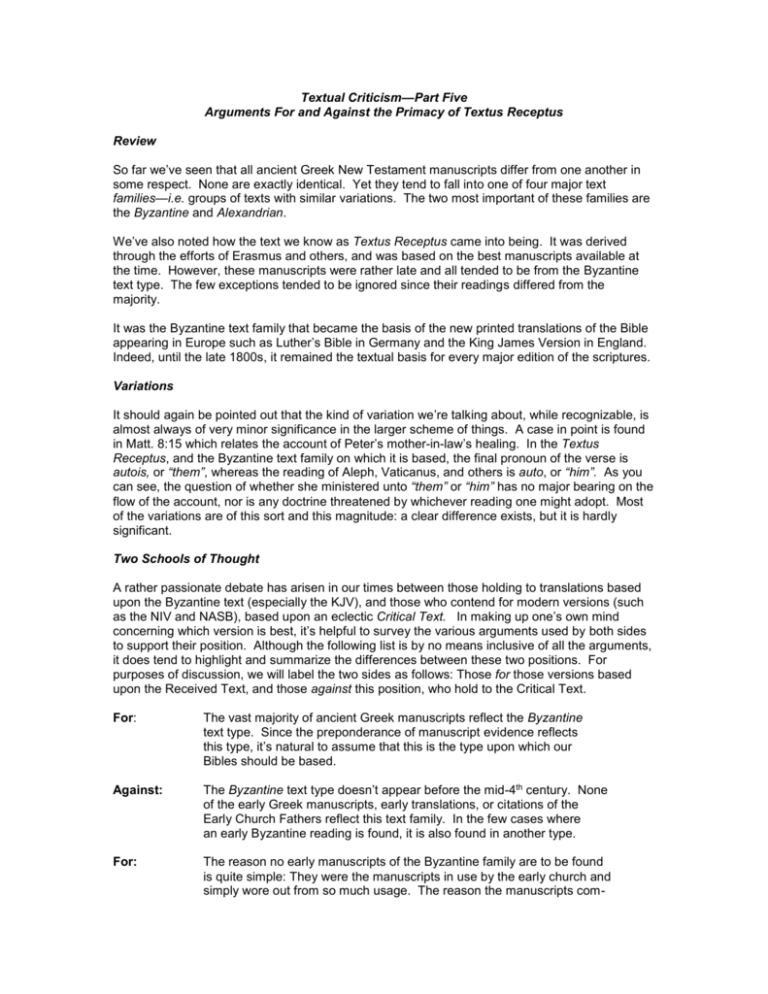

Textual Criticism—Part Five Arguments For and Against the Primacy of Textus Receptus Review So far we’ve seen that all ancient Greek New Testament manuscripts differ from one another in some respect. None are exactly identical. Yet they tend to fall into one of four major text families—i.e. groups of texts with similar variations. The two most important of these families are the Byzantine and Alexandrian. We’ve also noted how the text we know as Textus Receptus came into being. It was derived through the efforts of Erasmus and others, and was based on the best manuscripts available at the time. However, these manuscripts were rather late and all tended to be from the Byzantine text type. The few exceptions tended to be ignored since their readings differed from the majority. It was the Byzantine text family that became the basis of the new printed translations of the Bible appearing in Europe such as Luther’s Bible in Germany and the King James Version in England. Indeed, until the late 1800s, it remained the textual basis for every major edition of the scriptures. Variations It should again be pointed out that the kind of variation we’re talking about, while recognizable, is almost always of very minor significance in the larger scheme of things. A case in point is found in Matt. 8:15 which relates the account of Peter’s mother-in-law’s healing. In the Textus Receptus, and the Byzantine text family on which it is based, the final pronoun of the verse is autois, or “them”, whereas the reading of Aleph, Vaticanus, and others is auto, or “him”. As you can see, the question of whether she ministered unto “them” or “him” has no major bearing on the flow of the account, nor is any doctrine threatened by whichever reading one might adopt. Most of the variations are of this sort and this magnitude: a clear difference exists, but it is hardly significant. Two Schools of Thought A rather passionate debate has arisen in our times between those holding to translations based upon the Byzantine text (especially the KJV), and those who contend for modern versions (such as the NIV and NASB), based upon an eclectic Critical Text. In making up one’s own mind concerning which version is best, it’s helpful to survey the various arguments used by both sides to support their position. Although the following list is by no means inclusive of all the arguments, it does tend to highlight and summarize the differences between these two positions. For purposes of discussion, we will label the two sides as follows: Those for those versions based upon the Received Text, and those against this position, who hold to the Critical Text. For: The vast majority of ancient Greek manuscripts reflect the Byzantine text type. Since the preponderance of manuscript evidence reflects this type, it’s natural to assume that this is the type upon which our Bibles should be based. Against: The Byzantine text type doesn’t appear before the mid-4th century. None of the early Greek manuscripts, early translations, or citations of the Early Church Fathers reflect this text family. In the few cases where an early Byzantine reading is found, it is also found in another type. For: The reason no early manuscripts of the Byzantine family are to be found is quite simple: They were the manuscripts in use by the early church and simply wore out from so much usage. The reason the manuscripts com- prising the other text types are to be found at all and are of such an early date is because the early church recognized them as defective. They were, therefore, set aside and relegated to the “closet”, so to speak, before being discovered in these modern times. Against: If this was the case we should expect that there would be many generations of early copies made—but where are they? Further, in the writings of the Early Church Fathers, their quotes reflect every text family except the Byzantine. Who was wearing them out? This is but an argument from silence standing against the hard evidence that does exist. For: The vast majority of manuscripts were preserved in the Byzantine empire where Greek was spoken. The more ancient copies, from which the other text families are derived, were preserved only because of a geographical accident—i.e. the hot, dry climate of Egypt. Had such a climate been present in Constantinople we might well have early copies of the Byzantine family as well. Against: The fact that most Greek manuscripts reflect the Byzantine text type could also be relegated to a geographical accident. For, from about the 4th century onward, it was only in the Byzantine empire—a small pocket compared to the rest of the world—that Greek was a living language. Obviously, more Greek copies would be produced in that environment. Further, many of the Early Church Fathers, living in other places besides Egypt, cite the other text types. For: The Alexandrian text type rests almost exclusively upon the Vaticanus and Sinaiticus manuscripts, dating to the 4th century. So, there is no logical reason to suppose that this text type predated the Byzantine type. Against: The Alexandrian type is found in the citations of the Early Church Fathers and in several early translations. The earliest manuscripts are the papyri, dating from the 2nd and 3rd centuries. None reflect Byzantine readings. Most reflect a mixture of Alexandrian and Western readings. P75, for example, dated at about 200 AD, reads almost exactly like Vaticanus. For: The Byzantine text family is the family that has been used by a majority of believers and churches. It is, therefore, clearly the text type favored by God’s Providence. To embrace a version of the Bible based upon another text type is to ignore the clear fact that God intends His people to have this text rather than another. Against: If what the majority does is our standard of truth, we would have to embrace infant baptism, Arminianism, etc. Providence can be interpreted different ways: The same God Who preserved the Byzantine text type also preserved the others as well. Doesn’t it follow that we should use all the texts that Providence has preserved for us? For most of church history, the Byzantine text was preserved in but one, small corner of the world while the vast majority of Christians used the Latin Vulgate. For: The changes introduced in the other texts appear to introduce and support heresy. This is especially true concerning the doctrine of Christ’s Deity. This fact supports the view that these texts were recognized by the early church as having been altered by Arian copyists intent upon hiding this doctrine. So, the church recognizing the heretics hand, discarded these manuscripts, deeming them unworthy of being copied. Against: If this was the intent of the copyist, they were particularly inept at it! If their purpose was to eradicate or alter a key doctrine, why wouldn’t they systematically change other passages where the same doctrine is taught? Although such a program is easily detected in certain translations—such as the Jehovah Witness’s NWT—no such thing can be found in the underlying text. Further, if a passage such as I Jn. 5:7 had been in the Bibles of the early church, surely it would have been cited in the Arian controversy and the debates than ensued over it. For: The Byzantine text type, particularly as propagated in the KJV, is the text type blessed by God. It was the text of the Reformers and the Puritans, as well as the text type in use during the great revivals of the past. To embrace modern versions based upon another text family is to ignore the clear history of God’s dealings with His people. Against: This assumes they had a choice! In the case of the Reformers and the KJV translators, the Byzantine text was the only one available. This argument ignores the fact that there were calls from many quarters for revisions once better manuscripts were available. No one, including the KJV translation committee itself, claimed the position held by the KJV-only crowd today. For instance, in 1660, a number of Presbyterian and Puritan ministers presented to the bishops an “Exception Against the Book of Common Prayer”, the eight point of which reads, “A new Royal translation of the scriptures is to be uniformly introduced.”