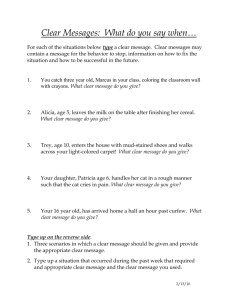

Community Asset Transfer as it is currently practiced and widely

advertisement

DRAFT VALUE THEORY OF DISCOUNTED COMMUNITY ASSET TRANSFER FROM STRUCTURED DIALOGUE, BIRMINGHAM 24 FEB 2010 This theory was derived from structured dialogue held at The Bond Warehouse, Fazeley Street, Birmingham on 24 February 2010. The structured dialogue was based around two stories focusing on the theme of ‘measuring worth’ related to the use of publicly owned buildings. It was commissioned as part of the Community Asset Transfer Development Programme, to evaluate and learn from the experience of Community Asset Transfer (CAT) in the city. Participants in the session were from various parts of Birmingham City Council and community organisations that had been involved in CAT, the Development Trust Association and Chamberlain Forum. Paul Slatter of Chamberlain Forum facilitated the session. The theory has been written up on the basis of the insights of members of this group recorded on the day. We have suggested calling the theory a value theory because it represents a set of ideas on values and valuation. We have suggested discounted community asset transfer because the discount is at the heart of what makes CAT different from an ordinary ‘market price’ transaction. OVERVIEW What emerged from the structured dialogue was a theory based on a distinctive picture of Community Asset Transfer informed by experience: The ownership of assets is less significant than the way they are managed and the uses to which they are put. The valuation of the social benefit of future uses should be the key question in discounted CAT. (It is, for example, more important than abstract ideas about the ‘worthiness’ of groups taking on ownership of assets). The boundary between ‘the Council’ and ‘the community’ is not so fixed or definite as it may be portrayed (and may not be so strongly divisive as the gaps that can exist between communities in the same neighbourhood). Real ‘community assets’ are, most significantly, people - their ideas and skills (‘human capital’) – rather than land and buildings. We found that: Page 1 The transfer of physical assets is not necessarily the best way to increase the capacity of community organisations. CAT does not take away the need for technical aid, grants and subsidies etc. Just because a community group has an asset transferred to it, does not mean it can do without access to other sources of support and the need for support may go on beyond the transfer of a physical asset. DRAFT To present freehold ownership of assets as the paramount issue in CAT is unhelpful: a range of options around ownership and management is possible, and desirable. Some buildings and land are net liabilities regardless of who owns them. FIXED ASSETS Land and buildings have value beyond their physical extent. They have ‘meaning’ to their neighbours - a social value beyond that accounted for as fixed assets on the balance sheet. Land and buildings may feel as if they ‘belong’ to a wider community of people who live and work in and around them. They may play a part in forging community sense of belonging to an area. Users of public assets, in particular, may feel a particularly strong sense of ownership over ‘their’ library or park etc. This effect can extend to privately owned neighbourhood assets. In most neighbourhoods, significant land and buildings are in private ownership. Private assets have social value too. Shops, pubs and post offices etc support all kinds of social, as well as private, uses. Both privately and publicly owned land and buildings can be net social liabilities. For example, empty and underused buildings may have a negative financial effect on neighbouring property. Neglected assets, whoever owns them, tend to demoralise, and devalue, neighbourhoods. Finding new uses for old buildings can change the way people feel about and an area. It may be socially desirable to have such buildings used to serve beneficial purposes – even if ownership is not transferred and the uses to which they are put are informal and not guaranteed in the longterm. The transfer of ownership of an asset can play a critical part in unlocking sustainable beneficial uses. To focus exclusively on ownership, however, risks missing some important points: How a building is used and managed often matter more than how it is owned. The physical process of renovation can lead to change and re-valuation of assets, but the fundamental changes come through changed relationships. Land and buildings that feel owned in some sense by the community, for example, can act as catalysts for cohesion: bringing people together through the way they are run. VALUATION The value of an asset depends on the way it is used and the ways it could be used in future. The value of land and buildings depends, therefore, on the neighbourhood that surrounds them; the wealth and ingenuity of the communities that share it; and on how that neighbourhood and those communities might be expected to develop. Page 2 DRAFT Under-used or derelict land and buildings generally have a negative effect on the neighbourhood in which they are located. The owner of such assets may, even so, place a high value on them on the basis of their potential. Speculation, like this, feels like ‘free-riding’ on the back of a neighbourhood. There is often widespread support for action against landlords – including public bodies - who leave properties empty or under-used. The defining feature of Community Asset Transfer (CAT) is that the ownership of land and buildings is transferred at less than market value. The discount is justified on the basis that the transfer in ownership facilitates greater social value by enabling new uses for old assets. Working out the value of the discount is a central challenge in enabling and managing the process. If the discount is too small then public assets will remain under-used when they could have been profitably transferred to a community group. If the discount over-estimates the social value of transfer then assets will be transferred which it would have been more socially beneficial to retain in public ownership. The discount needs to reflect accurately the social value added through transfer. There is sometimes an assumption that transfer to community ownership will automatically add value to all sorts of council assets and/or leave community groups more like ‘social enterprises’; able to compete effectively in the market for commissioned public services. In the real world, authorities and community groups need to challenge this assumption. Will CAT actually lead to increased social value? Will the process actually leave the principles and identity of the group intact? ‘BOTTLING THE GENIE’ To succeed in transferring assets through a community discount process typically requires ‘grassroots’ campaigning, negotiating and community organising skills and energy. These are not necessarily the same skills needed to create, enable and sustain uses. There is a tension: groups that are good at supplying the energy needed to shift ownership from State to direct community ownership are not necessarily capable of storing that energy in the form of structural and organisational arrangements needed to manage assets. The opposite is almost certainly true: some groups that might be excellent managers and exploiters of community assets are unable or unwilling to expend the considerable energy required to go through a discounted transfer process. Does the acceptance and adoption of the community assets agenda by local authorities support or undermine civil activism? There is a risk that all that comes with owning property stifles the creativity of groups. Risk is a key factor. Community groups are more or less able to manage risk effectively but are, in general, less able than public or larger voluntary organisations. At the same time, they are often more willing to take on risk than statutory Page 3 DRAFT organisations. Some approaches to community asset transfer encourage community activists and groups to take on too much risk in both senses, ie: risk that is ‘uneconomic’ – assets that are worth less than they are supposed to; risk that is unsuitable – assets that are potentially worth a lot but which would take up more time and energy than is available’. The challenge is to enable ‘the system’ to include community groups without having them become just another part of the system. It is worth looking at: the idea of ‘sustainability’ - which doesn’t necessarily mean a project has to last indefinitely; ways local authorities have found of recognising the value innovation and enterprise in communities; ways for the authorities to access and use the frontline knowledge and wisdom of neighbourhood and local staff; the timescales for change – the changes groups need to make in the way they govern and account for themselves are likely to take longer than the time taken to sign legal transfer documents. GOVERNANCE Community organisations need to be extremely robust to be successfully involved in CAT. They may need considerable support especially if they rely on volunteers as staff and trustees. Authorities may need to probe further into how an organisation looking to go through CAT actually works’ in practice (ie who actually makes decisions and how) rather than relying on explanations on paper. Key issues include: accountability, structure and transparency/open-ness. Both sides need to be clear about why organisations want to take on an asset. The perils of ‘chasing the money’ are real but CAT may also be a force to galvanise necessary changes within groups and communities: change in ownership can ‘shock’ a community out of ‘apathy’. ‘Positive thinking is a blessing and a curse’: dreams and ambition are not enough – the valuation of asset discounts needs to be on the basis of a coherent business plan. LEARNING AND CHANGE Whilst most elected members may support the idea of community asset transfer, there is not necessarily a shared and strategic picture of what it might achieve; why it might be done; and how they could play a useful role in it as community champions and place-shapers. Authorities’ commitment to the process may still be quite superficial. Making a success of community asset transfer appears to rely on the resourcefulness and initiative of committed middle-ranking officers. There may not be much evidence that their commitment to making CAT work is much valued or Page 4 DRAFT supported within the local authority. If these officers ‘move on’; or if there is no further money incentive for transferring assets, then CAT may lose its ‘buzz’. THE PROCESS The process of asset transfer (as well as its end result) can be beneficial to the partners involved. It can be the catalyst for wider change in community organisations that take on the ownership and management of fixed assets: confronting them, for example, with the need to invest in their ability to act as social enterprises. For local authorities and others transferring assets, the CAT process can provide a focus for improving the way they deal with – and value the work of – community groups. This includes, for example, changing the language authorities use to describe community partners and their relationships with them. The CAT process can also, however, be stressful and even damaging. In particular, imposing tight deadlines on agreements (eg, to fit in with external funding arrangements) adds to the stress of the process. The CAT process needs to be managed flexibly and be made responsive to local opportunities and conditions: there need to be different approaches in different places. No approach to asset transfer is likely to be value neutral: different approaches to asset transfer make potential projects more or less feasible. In particular, practitioners should understand that the approach taken to valuation will favour, prejudice or exclude the cases to be made for the transfer of different assets. Policy-makers should highlight flexibility and subjective factors in any method of valuation they put forward. Page 5