Subtopic 2: Critical Thinking

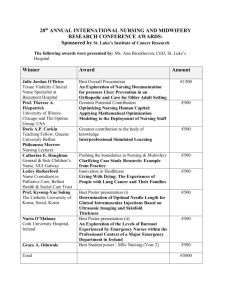

advertisement

Subtopic 2: Critical Thinking Introduction Critical thinking is vital to nursing practice. Nursing has evolved from an occupation to a profession, with skills based on well-developed knowledge. Nurses today have greater autonomy and a growing demand for expanded critical thinking abilities and decision making. Martin (2002) emphasizes: One important role of nurses is decision-maker regarding client care. Decisions made by nurses often involve complex problems concerning the physical and psychosocial well-being of clients and interaction with other disciplines. As a client’s status changes, the nurse must recognize, interpret, and integrate new information and make decisions about the course of action to follow. For satisfactory client outcomes, complex decision-making goes hand in hand with critical thinking (p. 2). Nurse educators must continually revise curriculum and classroom strategies to meet the challenge of preparing students for dynamic healthcare changes. Emphasis is placed enhancing critical thinking skills. Reference Martin, C. (2002). The theory of critical thinking of nursing. Nursing Education Perspectives, 23(5), 243-247. Examples of Critical Thinking Strategies Case Studies Concept Mapping Subtopic 2: Critical Thinking Case Studies In contemporary higher education, case studies are in some ways similar to storytelling. Most cases are, in fact, stories centered on persons or organizations that must make or have made choices involving dilemmas portrayed in the cases. Often, cases are open-ended or decision forcing and students are expected to identify with the cases and formulate their own responses to the dilemmas while providing analysis and rationale to support their actions. A strength in case education is the way that cases can help students look at dilemmas from the inside-out, and not merely act as external critics (Simmons, n.d.). Cases are traditionally taught using discussion and interactive formats. Instructors accustomed to lecturing often find cases to be a very different approach to teaching. Some have described the role of a case teacher as similar to that of an orchestra conductor with the students representing the musicians. A conductor does not actually play the instruments but rather guides and directs the musicians to contribute to the overall effort. Similarly, a case teacher guides students through the maze of a case discussion by questioning, redirecting questions, clarifying, probing and highlighting points or issues--but not by dictating a predetermined solution or bias. In addition to discussion of a case by an entire class, cases can be approached using small group collaborative learning strategies or integrated writing assignments. Nevertheless, it is customary to conclude with a structured discussion of a case involving the entire class in order to summarize key points and to obtain a sense of closure to the case. If there is a case epilogue, it can also be disclosed to the entire group as part of the discussion (Simmons, n.d.). Case studies can be developed with varying levels of difficulty; ranging from the simple application of principles of vital signs to the application of multiple concepts in the care of the client with diabetes and end stage renal disease. Types of Case Studies Vignettes Before Class Case Studies Unfolding Case Studies Vignette or Window (Quickie)- These brief cases provide real-world application without taking up much time (Herrman, 2002). Below are the steps to follow in the development of a vignette: (Mahimeister, 2000) 1. Create to describe a critical incident, which requires immediate nursing response or intervention. Life-threatening event Need for immediate protection Removal of significant safety hazard Clarification of unsafe order 2. Provide major cues: Describe essential aspects of problem Describe “Classic Signs” of problem Possible Faculty Question: “What is the immediate threat?” 3. Describe situation requires unequivocal priority of first action What lead you to identify the problem? 4. Explore methods for implementing plan. 5. Allow student to make incorrect diagnosis and planned intervention. Possible Faculty Questions “How can you help this client?” “How fast do you have to act?” “What could happen if the problem is not resolved?” “How will you correct this problem?” “What do you need?” 6. Determine if outcome goals have been achieved. 7. Discuss the consequences of error as function of evaluation. You are giving the first dose of IV Ampicillin to the client for a postoperative infection. It is 11:30 PM. The client is sleeping when you enter the room. You are running late because of several new admissions. You decide not to wake the client. You quickly hang the drug and move on to other tasks. Fifteen minutes after you started the medication, the client puts on the call light. When you enter the room the client is sitting in a high Fowler’s position and states, “My ears are popping and itching. The right one is completely closed up.” The client looks extremely anxious. As you approach the bed, the client adds, “my tongue feels weird, swollen… The client appears to struggle for breath. As you move the client, you note that the client is wearing an Allergy Alert bracelet for Penicillin. Possible Faculty Questions: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. After calling for help, the priority action is: What do you think is the physiologic cause of the client’s complaint? What is the most appropriate nursing diagnosis for this problem? What equipment will you need? Can you anticipate any special drugs, supplies, or equipment that may be needed? Is there anything that could have been done to prevent this problem? References Mahimeister, L. (2000). Supplemental Materials of Creative Teaching for Nursing Educators. Try it yourself: Develop a quickie or vignette case study related to content you are teaching. Before Class Case Study Assigning case studies that students must read and research in order to answer the questions before class adds to the value of time spent in class clarifying concepts and identifying potential test areas. Students become actively involved in reading, writing, and hearing the concepts (Hermann, 2002). You are working in the office of a family practitioner. MM comes to the office because over the weekend she had her blood sugar checked at a health fair and was told she needed to see her physician. The form from the health fair indicates that the random blood sugar done revealed a result of 310 mg/Dl. MM is a 42 year old Mexican American woman. Assessment reveals the following findings: Ht. 5’ 6”, Wt. 210 lbs. Vital signs are: B/P 192/146, P-88, R- 18, and T- 98.6. MM’s mother and two maternal aunts have type 2 diabetes mellitus. MM has smoked 1-½ packs of cigarettes daily for over 25 years; she admits she should get more exercise. Her only complaint is increasing fatigue over the past month and mild nocturia. 1. List the major risk factors for type 2 DM. Place a check next to the risk factors that MM has. 2. What manifestations of type 2 DM are present in the assessment? What are some others to be alert for? 3. The physician suspects type 2 diabetes. What diagnostic test/tests would confirm this diagnosis. 4. The physician discusses his diagnosis with the client. In talking with the client after the physician leaves, the client tells the nurse, “ I know that if I would stop eating “sweet things” I would not have diabetes.” How would you correct her understanding of the disease using understandable terminology? 5. Why would it be appropriate to ask the client if there is history of previous cardiac or heart trouble? 6. Identify three content areas of diabetes education that are important for clients with newly diagnosed diabetes. Identify three learning objectives for each content area. Try it yourself: Develop a case study that students would receive prior to class in a content area of your choice. Include: Scenario Questions to explore with students Unfolding Case Studies In today’s health care environment, the nurse must be able to obtain, analyze, and synthesize available data about the client and plan nursing care accordingly. This requires an experienced level of critical thinking and communication. The unfolding case study actively involves students and allows them practice time to individually, as well as collectively, solve problems they may encounter in clinical situations (Ulrich & Glendon, 1999). An unfolding case study usually contains three paragraphs; however, the instructor could design as many as they need to meet their learning goals. The first paragraph sets the stage for the scenario. It includes: Pertinent background information related to the characters in the case The initial situation Focused questions. Seven 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. areas to address when structuring the case: Purpose Biographical data Context Content Focused questions Cooperative-learning strategies Reflective writing Students can be given the case before class to help them pick out important concepts from the required readings. The instructor may occasionally want to intermittently collect the partially completed case studies to ensure proper class preparation by the students. In class, the instructor may want to begin with a 10-15 minute lecture on the topic of the case or just divide students into groups of 4-6 students. Then direct the student groups to process the case, one paragraph at a time, using the cooperative strategy of your choice: . "roundtable"; "think, pair, and share"; and "pass the problem." Paragraph #1 Example: Day 1, 1000. The client, a 62-year-old female of Native American decent is admitted to the hospital with increased fatigue, lethargy, and occasional confusion from chronic uremia secondary to End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD). The client has a long history of diabetes mellitus resulting in permanent damage to the kidneys. Diagnostic test ordered include: Renal scan and ultrasound, Hgb & Hct, BUN, serum creatinine, creatinine clearance, serum electrolytes, urinalysis, urine for C&S, fasting blood sugars, and fingerstick blood sugars AC&HS Focused Questions: 1.Discuss the cultural/ethnic considerations of clients with ESRD. Which cultures have a higher incidence of ESRD? 2. Identify the purpose of each diagnostic test ordered and why these tests would be needed with a diagnosis of ESRD. 3. Develop and prioritize five nursing diagnosis for the client and three interventions for each diagnosis.. After all three groups have finished, each group must pass the problem to another group. Each group processes their list of nursing diagnoses and interventions, refining and adding more to the list; groups present their findings. (Ulrich & Glendon, 1999) The second paragraph is revealed. This paragraph could reflect a change in time, build on the last paragraph, or include a new focus. Students again process the questions and share the findings through cooperative-learning exercises. Paragraph #2 Example Day 3, 1100. The client’s renal status has continued to deteriorate. Creatinine clearance is 6 ml per minutes and the client is showing evidence of fluid intoxication despite conservative measure to restrict fluid. PB 160/96, weight has increased by 5 lbs. Since admission, 2+ pitting edema noted in ankles and feet, fine crackles are present bilaterally in bases of lungs, jugular vein distention is evident. The doctor has prepared the client for the possibility of hemodialysis. Students again process the questions of this paragraph and share the findings through cooperative learning exercises. Focused Questions Example: 1. What are included in conservative nursing measure to prevent fluid volume excess in clients with renal disease? 2. Explain why the client’s symptoms may develop in a client with ESRD. 3. Compare and contrast peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis. What are the advantages and disadvantages of each? Groups are called upon to report At this point any further paragraphs are sequentially revealed, building on the case or changing its focus. Paragraph #3 Example: Discharge day. The client had an internal arteriovenous fistula surgically created two days ago. She will receive hemodialysis through a temporary access percutaneous cannula in her right subclavian until the fistula is ready for use. The nurse schedules the client for dialysis at the outpatient dialysis center three times per week. She is scheduled for a doctor’s appointment in one week at which time she will have serum electrolytes and a CBC drawn. The dietitian has met with the client and instructed her on fluid, sodium, and potassium restriction and a low protein, 2000 calorie diabetic diet. Mary lives alone on a fixed income. She expresses concern regarding her ability to get to the dialysis center three times per week and her financial ability to afford the dialysis. Focused Questions Example: 1. Considering discharge planning, what other areas would the nurse investigate with the client? 2. What are some of the options the nurse might explore with the client regarding transportation and financial resources? 3. How has the ESRD Medicare Program assisted individuals with renal disease? How can the nurse help the client access this resource? Report each group's findings. The final step is an individual reflective writing exercise that could encourage students to plan for their future learning needs, to think about and share individual reactions, and to reflect on and thus reinforce the learning experience. Reflecting Writing Prompt: If the client does not do well on dialysis, renal transplantation may be the only other option. Considering the scarcity of donor organs, the client will be placed on a waiting list with many others. Recently, there has been public debate about donor organs being given to someone who may have damaged their organs through drug abuse or chronic alcoholism. How do you feel about this matters? What are some of the ethical issues that must be considered in such a debate? Try it yourself: Develop an unfolding case study for a topic of your choice using the attached worksheet. Unfolding Case: Paragraph1:_______________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Focus Question 1. 2. 3. Paragraph 2: _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Focus Question 1. 2. 3. Paragraph 3: _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Focus Question 1. 2. 3. Reflective Writing _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Subtopic 2: Critical Thinking Concept Mapping Concept mapping is a technique that allows students to understand the relationships between ideas by creating a visual map of the connections. Concept maps allows the student to (1) see the connections between ideas they already have, (2) connect new ideas to knowledge that they already have, and (3) organize ideas in a logical but not rigid structure that allows future information or viewpoints to be included. Nursing students face a great need to understand the larger questions and problems of their chosen field. Without understanding, students may only commit unassimilated data to short-term memory and no meaningful learning will occur. Meaningful learning is most likely to occur when information is presented in a potentially meaningful way and the learner is encouraged to anchor new ideas with the establishment of links between old and new material (All & Havens, 1997). Concept mapping is an effective teaching method for promoting critical thinking and is an excellent way to evaluate students’ critical thinking because it is a visual representation of a student’s thinking. The concept map is an effective teaching tool that is fun, interactive, and effective. It can be used in a variety of settings. The concept map mirrors more closely real clinical situations by being dynamic as priorities shift. It is an innovative teaching tool that engages the student and prepares the student for future clinical decision-making in a complex and diverse healthcare environment Description: A concept map consists of nodes or cells (often a circle) that contain a concept, item or question and links (lines). The links are labeled and denote direction with an arrow symbol. The labeled links indicate the relationship between the nodes. Words are used to label the links in order to more explicitly depict relationships. Critical Questions: What is the central word, concept, research question or problem around which to build the map? What are the concepts, items, descriptive words or telling questions that can be associated with the concept, topic, research question or problem? Suggestions: Use a top down approach, working from general to specific or use a free association approach by brainstorming nodes and then develop links and relationships. Use different colors and shapes for nodes and links to identify different types of information. Use different colored nodes to identify prior and new information. Use a cloud node to identify a question. Gather information to a question in the question node. Constructing a preliminary concept map is helpful. This can be done by writing all of the concepts on Post-its, or by using a computer software program. Post-its allow a group to work on a whiteboard or butcher paper and to move concepts around easily This is necessary as one begins to struggle with the process of building a good hierarchical organization. Computer software programs are even better in that they allow moving of concepts together with linking statements and also the moving of groups of concepts and links to restructure the map. They also permit a computer printout, producing a nice product that can be e-mailed or in other ways easily shared with collaborators or other interested parties (Novak, n.d.). MindMapper (http://www.mindmapper.com/homepage.htm) SmartDraw (http://www.smartdraw.com/specials/flowchart.asp) Concept Draw (http://www.conceptdraw.com/en/products/mindmap/main.php) SMART Ideas (http://www.smarttech.com/products/smartideas/index.asp) Inspiration (http://www.inspiration.com/productinfo/Inspiration/index.cfm) Knowledge Manager (http://www.knowledgemanager.us/KM-KnowledgeManagereng.htm) Teaching and Evaluating with Concept Maps Concept mapping is very useful in student preparation for clinical experiences. When used for the assessment and care of a patient with multiple health problems, data gathered allows the student to create a concept from the concepts or data collected. A common way to begin a concept map is to center the “reason for seeking care” or medical diagnosis on a large blank paper. Assessment data are arranged and linked to the center concept according to how the student thinks they fit bets. As concepts or data are added, links and relationships become evident and may change. Grouping and categorizing concepts give a holistic aspect to clinical decisions (King & Shell, 2002). The concept map enables students to synthesize relevant data such as diagnoses, signs and symptoms, health needs, learning needs, nursing interventions, and assessments. Analysis of the data begins with the recognition of the interrelatedness of the concepts and a holistic vie of the client’s health status as well as those concepts that affect the individual such as culture, ethnicity, and psychosocial state. Once the preliminary concept map is complete, answering additional questions enable the student and instructor to make connections between concepts and begin formulating judgments and decisions. Once complete, the student and the instructor see all components simultaneously, providing a deeper and more complete understanding of the client’s total needs. Development of the concept map forces the student to act upon previous knowledge, connect it with new knowledge, and apply it. It requires the student to have a mental grasp of the situation, rather than relying on rote memory. Review of the map with the student gives the instructor an opportunity to evaluate the student’s thinking and an opportunity for immediate feedback on discrepancies and “missing links” (King & Shell, 2002). Typical data from a patient record. These data are typical of what students nurses find in medical records when gathering information for care plans or other assignments (King & Shell, 2002). Sample Concept Map with fictitious client data (King & Shell, 2002). Concept Mapping for Clinical Care Planning Castellino and Schuster (2002) describe the use of concept care plans instead of the column format care plans. Both students and faculty found that the concept care plans were specific to the client, concise, and organized care. The concept maps enabled a holistic view of the client and covered all client problems, and students learned to integrate and understand relationships between client problems. Faculty found that students learned to think critically and did not copy care plans from books as they did when using the column format. Schuster (2000) describes in detail the use of concept maps to replace traditional column care plans. Step 1: Based on clinical data collected, students develop a basic skeleton diagram of the health problems. The client’s major medical diagnosis is written in the middle and then associated nursing diagnoses are added flowing outward. The nursing diagnoses written on the map are the actual problems, not potential problems. At this stage of the care planning process, it is more important that students recognize and focus on major problem areas. Step 2: Data to support diagnosis. In this step, students analyze and categorize data gathered. Students identify and group priority assessments related to the reason for admission and identify and group clinical assessment data, treatments, medications, and medical history data related to nursing diagnoses. Step 3: Relationships between diagnoses. Students can use different colored pen, dotted lines, etc to indicate relationships. This is illustrated by dotted lines in the Figure below. Faculty can verbally ask students to explain why they linked diagnoses if not obvious. A student soon recognizes that most of the problems the patient has are interrelated. Students and faculty can see the whole picture of what is happening with the client by looking at the map. Step 4: Nursing interventions and evaluation. Students number each medical and nursing diagnoses on their map. Either on the back of the map or a separate page, corresponding nursing interventions are listed for each of the numbered nursing diagnoses on the map. The interventions include key areas of assessment and monitoring as well as procedures or other therapeutic interventions. Faculty can have students write or verbally discuss rationale for nursing interventions. Step 5: Using the Map During clinical, students update the map in order to evaluate effectiveness of nursing care. Group Activity Concept mapping can also be used as a group activity. Initially, it may be more effective if the instructor demonstrates the development of a concept map from raw data and asks students as a group to make links, associations, and conclusions while emphasizing the dynamic nature of the concept map as new or changing data is added. King and Shell (2002) the use of concept mapping as a teaching tool in clinical conferences. Using actual client data, the students are instructed to analyze and synthesize diagnoses, sign, symptoms, health needs, ethical/legal concerns, leadership/management issues, as well as nursing interventions that included assessment, planning, client teaching needs, and evaluation. Discussions allowed students to make connections not previously appreciated. This exercise offers the opportunity for increasing knowledge of client situations and practicing clinical decision making. Try it yourself: 1. Select a topic of choice, perhaps a medical diagnosis and relevant client data. Write the concepts on post-it notes (perhaps using different colors to represent concepts and examples). 2. Arrange the pieces of paper, on a poster board, so that the ideas go directly under the ideas they are related to (often this is not possible because ideas relate to several concepts). At this point, add concepts that help explain, connect, or expand the ideas. 3. Draw lines from the main concepts to the concepts they are related to. It may be necessary to rearrange the notes of paper. 4. Label the lines with “linking words” to indicate how the concepts are related. 5. Copy the results onto a single sheet of paper. 6. Use of computer software will enable you to manipulate nodes and links. References: All, A., & Havens, R. (1997). Cognitive/concept mapping: A teaching strategy in nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 25(6), 1210-1219. Castellino, A., & Schuster, P. (2002). Evaluation of outcomes in nursing students using clinical concept map care plan. Nurse Educator, 27(4), 149-150. Glendon, K., & Ulrich, D. (1997). Unfolding case studies: An experiential learning model. Nurse Educator, 22(4), 15-18. Glendon, K., & Ulrich, D. (2001). Unfolding case studies: Experiencing the realities of clinical nursing practice. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Herrman, J. (2002). The 60-second nurse educator: Creative strategies to Inspire Learning. Nursing Education Perspective, 23(5), 222-237. King, M., & Shell, R. (2002). Teaching and evaluating critical thinking with concept maps. Nurse Educator, 27(5), 214-216. Mahlmeister, L. (2000, March). Critical thinking through case studies. Workshop presented at Creative Teaching for Nursing Educators, Memphis, Tennessee. Novak, J. (n.d.). The theory underlying concept maps and how to construct them. Retrieved from http://cmap.coginst.uwf.edu/info/ Schuster, P. (2000). Concept mapping: Reducing clinical care plan paperwork and increasing learning. Nurse Educator, 25(2), 76-81. Simmons, S. (n.d.). An introduction to case education. Retrieved March 30, 2003, from http://www.decisioncase.edu/intro.htm Ulrich, D., & Glendon, K. (1999). Interactive group learning. NY: Springer Publishing. Additional Sources: Castillo, S. (1999). Strategies, techniques, and approaches to thinking: Case studies in clinical nursing. Philadelphia: Saunders. END of Subtopic 2: Critical Thinking Strategies For Continuing Education Credit complete the Subtopic 2: Quiz and submit the Subtopic 2 Evaluation form.