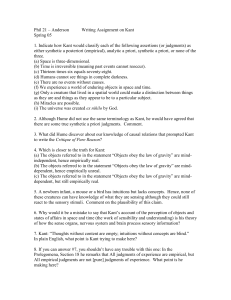

[2] `Kant`s Principle of Purposiveness, and the Missing Point of

advertisement

![[2] `Kant`s Principle of Purposiveness, and the Missing Point of](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007532087_2-40c1e5951c24e0b0354e126f1adaf45a-768x994.png)

Lines of Grammar. Auburn, March 2009. Lines of Grammar between Kant and Wittgenstein Avner Baz I am very happy for the opportunity this conference has given me to go back to Kant, and to beauty. Years ago in Tel-Aviv I was young enough to find not only exciting, but true, Kant’s proposal in the Critique of Judgment that, somehow, judgments of beauty bring out, or make explicit, capacities and sensitivities necessary for putting our world into words more generally, which means that, in seeking to share these judgments with other people, we put our wider attunement with them to the test. And I was further struck by the seeming affinity between Kant’s proposal, as I understood it, and Wittgenstein’s likening the understanding of a sentence to the understanding of a theme in music (PI 527), or a genre picture that does not purport to represent some particular worldly moment and is therefore not to be understood, or assessed, in terms of its faithfulness to some such moment (PI 522). By reminding us of the practice and experience of aesthetic evaluation, I was in those early days bold enough to argue in my masters thesis, Kant and Wittgenstein were both seeking to free us from the grip of a conception of human discourse that in philosophical moments makes us imagine a grounding for it in which we ourselves would not be implicated. I believe I read just a little too much of Wittgenstein into Kant back then. A few years later, in Chicago, I was working on an interpretation of Wittgenstein’s remarks on aspect perception, and it struck me that Kant’s notion of ‘subjective universality’ was helpful in capturing the tone, or force, of the expression of seeing an aspect; not so much in the case of the famous duck-rabbit and other schematic 1 Lines of Grammar. Auburn, March 2009. drawings encountered in artificial contexts, but when we truly are struck by a new aspect of something familiar and come to see it altogether differently. A Wittgensteinian aspect, like Kant’s beauty, I argued, is neither merely subjective nor fully objective—which is why it makes sense to call upon others to see it, just as we call upon them to see the beauty of something. Like Kant’s beauty, a Wittgensteinian aspect is not a property of the object; but neither is it merely in the eyes of the beholder.1 At that time I was already moving away from Kant. Largely under the continuing influence of Wittgenstein, I grew suspicious of the occasional exhilarating sense that everything fits together, or anyway ought to, and of grand philosophical systems— however much truth one may find in them—that promise to capture everything worth capturing philosophically, and to do so once and for all. I also read around that time Stanley Cavell’s ‘Aesthetic Problems of Modern Philosophy’ for the first time and found true, and liberating, his description of Kant as offering us, in his analysis of judgments of beauty, nothing more, nor less, than a piece of Wittgensteinian grammar. This pressed upon me the question of how much of Kant’s grand transcendental story one had to buy in order to entitle oneself to finding true and useful particular moments in that story. This question may be said to be my topic today. One persistent problem I have had with Kant, though no more with him than with much of the rest of the tradition of western philosophy, is that the question of the point of putting something into words—the point, if you will, of conceptualizing this or that bit of sensible manifold—is altogether missing from his account of what he calls experience. The connection between the content of judgments and human intelligibility as a function of what we care about, and why, and in what specific ways, is missing from that account. 2 Lines of Grammar. Auburn, March 2009. As a result, I argue in a more recent paper, Kant places our encounter with beauty within a picture of the human being in the world that is not true of my—or, I am suggesting, your—being in the world. Kant’s faculty of ‘reflective judgment’, which is repeatedly presented in the first two introductions that he wrote for the third Critique as facing the ‘enormous task’, or ‘project’, of unifying and systematizing ‘the whole of nature’— guided by its principle of purposiveness, but with no transcendental assurance that its task could ever successfully be accomplished—is neither your faculty nor mine, I argue in that paper; and this means that Kant’s ‘beauty’ can’t quite be your ‘beauty’ or mine either.2 Since I wrote that paper I have read a couple more recent interpretations of the third Critique—most recently Rachel Zuckert’s impressive book3—that, by way of the principle of purposiveness, find a grounding or metaphysical legitimization for judgments of beauty, not just in the conditions of the scientific or scientific-like work of systematically unifying the whole of nature, but rather in the conditions of our very ability ‘to formulate [or form] empirical concepts’,4 and therefore, presumably, in the very ‘possibility of experience’.5 Ashamed as I was in the face of those interpretations, for having failed to read Kant as charitably as his text makes possible, I found that I still couldn’t recognize myself in the picture of the ‘we’ that I was being offered. For one thing, and here I am coming out of a sort of philosophical closet, I do not think I ever formed a concept; and I do not think I am alone in this. Nor, for that matter, can I easily recall or imagine a situation that I would happily describe as my having ‘applied a concept’ to, or ‘conceptualized’, an ‘intuition’.6 Rather, I came to talk, in a world that my body had already begun to make sense of, by way of engagement, and in which language was already being spoken and things, for the most part, already had their 3 Lines of Grammar. Auburn, March 2009. names, and their place. Gradually, speech became an extension of my bodily engagement with a world of which the speech of others was gradually becoming a part. This is how I came to possess the concept of ‘tree’, for example—by which I mean: how I became a competent employer of the word ‘tree’. It is possible that, as part of my training, my elders pointed out, not subjective intuitions, to be sure, but trees to me, either in the world or in picture books, and encouraged me, not to apply the concept, but just to utter the word, showing their approval every time I did it right—that is, in a way that they were ready to count as ‘right’. Even if they happened to do this with ‘trees’, they surely never got to do it, nor could conceivably do it, with most of the words that I was coming to master in those early years. What is at any rate certain is that I heard the word ‘tree’ used in various contexts, woven significantly into increasingly better understood activities—father suggested that we sit by this or that tree, for example, mother remarked how lovely it was to sit in its shade, sister pointed out a bird hiding in its branches, brother was found hiding behind it or was told to get off of it, we planted a tree in our garden and waited for it to grow…—and gradually, though fairly quickly, I cottoned on. Initially I might have made a few funny mistakes or used the word creatively but non-standardly; but soon enough I came to master the word ‘tree’. I came to know its specific powers and riches—where that meant, in part, coming to know the place and significance of trees in our world. This quasi-Augustinian story explains nothing; and, like Augustine’s story, it becomes increasingly inadequate and potentially misleading as we move from words like ‘tree’, ‘table’, ‘Joe’, and ‘red’, to the sorts of words that have given philosophers trouble for millennia: ‘know’, ‘understand’, ‘mean’, ‘judgment’, ‘experience’... But it is, I 4 Lines of Grammar. Auburn, March 2009. suppose, a close enough description of how I came to what you might call possession of the concept of tree. I am quite sure that I did not come to possess that concept by seeing or calling to mind firs, willows, and lindens—or their Israeli relatives—comparing them with one another, reflecting on what they had in common and abstracting from impertinent differences.7 Though I might have done something like that at a later point, as Robert Pippin suggests, bethinking myself of things I already knew to be trees, in order to make clearer to myself a concept I already possessed.8 If I ever did do that, however, I did it in a world that already had trees in it, was otherwise already well familiar, and was not significantly less well understood, empirically, than it would ever become. There are other elements of Kant’s theory of experience that I find patently implausible. For example, it seems clear to me that our empirical concepts do not form a hierarchical unified system, but connect with each other in any number of ways and directions that are often quite unexpected, thus forming an endlessly complex network. This should become clear the moment we remind ourselves that concepts such as those of responsibility, shame, forgiveness, authority, membership, banishment, etc., etc., as well as, of course, concepts such as those of judgment, seeing, knowing, pleasure, etc., are no less important for the articulation of human experience than concepts such as those of fir and tree or whale and mammal. But it is not my aim today to mount a phenomenological attack on Kant’s theory of experience. Rather, I would like to articulate, and bring out the significance of, a methodological difference—a difference in philosophical approach—that seems to me to underlie many of the growing difficulties I have had with Kant. The approach that I want to contrast with Kant’s is, not surprisingly, Wittgenstein’s. It is encapsulated in the 5 Lines of Grammar. Auburn, March 2009. latter’s famous exhortation that we should replace explanation with description, if we wish to become clearer with respect to our concepts and thereby to find our way out of philosophical difficulties; not primarily because description is better than explanation as a way out of conceptual entanglements, I think, but because, all too often, it is precisely the philosophical demand for explanation that got us into difficulty in the first place. I do not think we can understand what Wittgenstein means by ‘description’ in this context unless we see it as an antidote to what he means by ‘explanation’; and neither notion is easy to understand. The best way of becoming clearer about a conceptual distinction, this or other, in philosophy and elsewhere, is to look at what it comes to in practice; so instead of explicating Wittgenstein’s distinction, as I understand it, I’ll try to put it to use. I begin with the following fact. In ‘Aesthetic Problems’ Cavell suggests that the ordinary language philosopher’s appeal to ‘what we should say when’ partakes of the grammar of judgments of beauty as characterized by Kant; I have found the same to be true of our giving voice to the seeing of an aspect.9 And yet, however interestingly connected with beauty, neither an aspect as Wittgenstein thinks of it, nor, certainly, ‘what we should say when’ insofar as it is pertinent to the resolution of philosophical difficulties, is beauty— not as Kant thinks of beauty, at any rate. In Kant’s system, however, subjective universality—this ‘speaking with a universal voice’ or offering our judgment as ‘exemplary’, calling upon others to see or acknowledge the presence of something whose presence we cannot prove or establish—is presented as a peculiarity of judgments of beauty. Between the full-fledged objectivity of empirical and moral judgments, and the 6 Lines of Grammar. Auburn, March 2009. mere subjectivity of ‘This sure feels good’ or ‘I like it’, there is in Kant’s system only room for aesthetic judgments of taste. This, it seems to me, is one reason for thinking that Kant’s system—however compelling—is to be suspected. I do not mean to deny that the philosophical imagination can and perhaps even should draw inspiration from the discovery of grammatical affinities such as the ones mentioned above. My point is just that the construction and maintenance of a philosophical system is only one way of pursuing such an inspiration, and might not be the best way of doing justice to the phenomena. Our philosophically interesting concepts, I have found, crisscross each other in complex and often unexpected ways that defy Kantian systematization and call rather for Wittgensteinian local elucidations in the face of particular difficulties. For example, it may well be true that the experience of being struck by an aspect is closer to the experience of being struck by beauty than it might initially appear. I am actually inclined to think this. In the Brown Book Wittgenstein likens the seeing of aspects to cases in which something—a piece of music, for example, or a bed of flowers—speaks to us, and we feel called upon to say what it says, but at the same time find that we cannot satisfyingly say it. A Wittgensteinian aspect, just like what a thing says when it speaks to us, and, we could add, just like Kant’s beauty, cannot be separated by means of description from the experience of the thing in the way that an objective property of it can be. If I tell you that the thing is red, or round, I may thereby be telling you all that there is to tell in this respect—all that I know and all that you need to know. If you trust my testimony, you may spare yourself the effort of looking at the object yourself, and even rightfully assure other people that the object is red or round on the 7 Lines of Grammar. Auburn, March 2009. strength of my word. But if I come to see, not a courageous face, but a face as courageous, then ‘courage’ alone, apart from the experience of seeing this face as courageous, will not adequately convey what I see. Likewise, according to Kant, the word ‘beauty’ will not adequately capture what we see when something strikes us as beautiful. The concept of beauty is not a ‘determinate’ concept, as Kant puts it (CJ 341). And in the same way, what we experience when something speaks to us cannot be separated, according to Wittgenstein, from the thing as experienced. To suppose otherwise, Wittgenstein proposes in the Brown Book, is to succumb to an illusion.10 One may go further and equate the beauty of something with its speaking to us in the way Wittgenstein describes. Heidegger sometimes seems to be doing this.11 There are arguably moments in which Wittgenstein does this,12 while yet, and not inconsistently I think, expressing impatience with the word ‘beautiful’ itself. 13 And Kant himself more or less does that when later in the third Critique he comes to equate the seeing of beauty with the seeing of what he calls ‘aesthetic idea’, which he defines as a ‘presentation of the imagination that prompts (veranlasst) much thinking, but to which no determinate thought whatsoever, i.e. no concept, can be adequate’ (CJ 314).14 The problem for Kant’s grand story, however, is that the connection he earlier insists upon between judgments of beauty and pleasure seems to have now been severed. To have something speak to you, to feel compelled to give voice to and thereby bring out something about it for no reason external to the thing itself—and hence, if you will, disinterestedly—is surely not the same as, nor even necessarily involves, finding pleasure in it. I know committed Kantians would insist that what Kant says about aesthetic ideas may be shown to fit with things that he says earlier about the place of pleasure in the 8 Lines of Grammar. Auburn, March 2009. experience of beauty; and if the history of Kant exegesis has taught us anything, any number of ways of showing this may be found. But what would be the point of insisting on this, given that the precise connection between a feeling of pleasure and the judgment of beauty is something that, so far as I know, no two interpreters of Kant have quite been able to agree upon? I do not deny that one could think of beauty as intimately connected with pleasure. All I am saying is that we needn’t think of beauty in this way, and that it is not clear that we should. In his later work Wittgenstein comes back again and again to the ways in which we distort our view of the mental phenomena we wish to understand. We try to answer the question of what some mental state or process or act consists in, by way of combining theoretical considerations and introspection of ‘what happens’ when we, for example, understand or read or mean or see something. When we reflect on presumed instances of such mental items in ourselves, we distort the intended object of our reflection not only by the mere act of turning our attention inwards, as it were, which is not part of what normally happens when we (say) understand or read or mean or see something, but also by looking at what happens ‘through the medium’ of the very concept we wish to understand (PI 177).15 Thus, if we have come to think on theoretical or proto-theoretical grounds of the encounter with beauty as essentially involving a feeling of pleasure, for example, we will invariably find that feeling present in such encounters, when we reflect on them. The phenomenon, to which our theory is supposed to be beholden, thus gets covered up by being seen under a theoretically engendered aspect. 9 Lines of Grammar. Auburn, March 2009. Wittgenstein’s antidote for such theoretically biased findings, as I said, is to describe language-games and resist the temptation to explain them by appeal to a hidden reality. Instead of trying to get at and capture the phenomena as they are in themselves, as it were, which really amounts to an attempt to see through the phenomena to their hidden essence, Wittgenstein urges that we start by reminding ourselves of the kinds of things we say about the phenomena, thereby revealing their ‘possibilities’ (PI, 90). There is a sense in which this is a deeply Kantian move, as Cavell has noted;16 but, as I understand the move, it ultimately throws Kant’s work itself into question, since the phenomena under investigation in Wittgenstein are not those investigated by the natural sciences, but rather are the ones under investigation in, for example, the Critique of Pure Reason: perception, judgment, knowledge… The Wittgensteinian lesson, at once Kantian and anti-Kantian, is that we get into philosophical trouble when we attempt to think of those as ‘things as they are in themselves’—i.e., apart from a consideration of the humble uses of ‘see’, ‘judge’, ‘know’, and other philosophically troublesome words, and the human conditions (needs, limitations, propensities, institutions…) that make these uses called for and (therefore) possible. The Wittgensteinian grammatical investigation is a way of becoming clearer with respect to our ‘concepts of experience', and hence the phenomena they delineate, without the postulation of Kantian or other mental machineries. To neutralize the distortions of introspection, the investigation typically involves a shift of focus from the first person to the third person. In the case of beauty, for example, Wittgenstein would have us ask when we would say of someone else that he was struck by the beauty of something (as opposed to merely finding it pleasing, say, or interesting), or that he was unable, or no longer able, 10 Lines of Grammar. Auburn, March 2009. or unwilling, to see or acknowledge the beauty of something, or that he tried to get another to see it, or that he confused the beauty of something with its utility or moral worth… And from there we may proceed to articulate the grammar of the concept of beauty, with an eye to the resolution of this or that philosophical difficulty. 17 This, Cavell has suggested, is what Kant does, and does rather well, in the Analytic of the Beautiful and later sections of the third Critique. I’m suggesting, however, that Kant’s thinking of beauty as essentially connected with pleasure is neither justified by the grammar of the concept of beauty nor useful for seeing it aright. And it gets us into difficulties rather than freeing us from them. Let’s us remind ourselves of the intra-systemic, architectonic, reasons Kant had for connecting judgments of beauty with a feeling of pleasure. For it’s not as if it is just obvious that judgments of beauty are based on, or express, pleasure. It was not obvious to Heidegger, for example;18 and it was not obvious to the rationalists to whom Kant was, in part, responding. And even Kant moves quite undecidedly between speaking of beauty simply as an object of liking (Wohlgefallen)—which may simply come to saying that we find beauty worthy in a particular way of our and others’ disinterested attention—and speaking of it as an object of pleasure (Lust). One can see how, at some point, everything fell together for Kant, in such a way that judgments of beauty just had to be intimately tied to a feeling of pleasure. The system demanded this.19 Start with the much-discussed problem of judgment from the first Critique:20 In empirical, objective, judgments we fit together concepts, which Kant thinks of as rules of unification, and (at the most basic level) sensible intuitions, to form cognitions of objects 11 Lines of Grammar. Auburn, March 2009. and so experience as Kant thinks of it; but evidently our doing so cannot itself be grounded in concepts or rules, on pain of infinite regress of judgments. It would appear, then, that if our judgments are not to be thought of as merely caused, and so as not being true judgments, they must be guided by feeling—by a sense of fit between intuition and concept, law and particular case. In seeking to communicate our judgments to others we tacitly rely on them to share this sense of ours; for if they did not, our judgments would presumably be ‘empty’ as far as they were concerned: mere formal moves in a formal system, with no connection to the world of sense—and so, presumably, with no ‘correspondence with their object’ (CJ 238). This is the presupposition of what Kant calls ‘Sensus Communis’. For the most part, our reliance on the sensus communis remains in the background: our communication with others runs smoothly and effectively enough, serves its purposes well enough, and so long as it does, our tacit assumption of a common sense receives all the validation it needs, by Kant’s lights. Given Kant’s way of thinking about empirical judgment, as a matter of unifying intuitions by means of concepts, and given the evident implausibility—unintelligibility, really—of seeking to ground judgments in concepts or rules, it is quite understandable why he came to think of empirical judgments as ultimately resting on nothing but a sense, and why he further thought that in communicating our judgments to others we must tacitly presuppose that our own sense is in fact common, shared. What is less clear is why Kant thought that, over and above the communication of empirical judgments, it must somehow also be possible for us to communicate directly to others our sense of fit itself—or, as he puts it, the felt ‘disposition of the cognitive powers for a cognition in general, and indeed that proportion which is suitable for making cognition out of a 12 Lines of Grammar. Auburn, March 2009. representation’ (CJ 238)—separated or abstracted from the production of any particular, ‘determinative’, empirical judgment (see CJ 290). I mean, it is one thing to say that if communication of empirical judgments, and hence perhaps the connection between our words and objects, is to be at all possible, it must be possible for us to communicate to others not just our judgments, but also our conviction in them, or lack thereof, and we must on the whole agree in our respective levels of conviction (cf. CJ 238). We should on the whole agree, for example, not only that this or that is a tree, say, but also that it is somewhat or quite uncertain—given its distance, or unusual shape, or the dim light, or the quality of the picture—whether it is or it isn’t. But why can’t our judgments and levels of conviction be all that there is for us to communicate and agree or disagree in? Why should there be in addition judgments directly expressive of the disposition of our cognitive powers toward each other upon encountering an object? It is one thing, when you’ve reached bedrock and your spade is turned, to call with a ‘universal voice’ upon the other, ‘Don’t you see?!’. It is quite another thing to call upon the other to share in the experience of the bedrock itself with you. The Deduction of judgments of beauty, Kant says, ‘asserts only that we are justified in presupposing universally in every human being the subjective conditions of the power of judgment that we find in ourselves…’ (CJ 290). But I confess not to have found the subjective conditions of the power of judgment in myself—not until I read the third Critique for the first time, at any rate, and had Kant suggest them to me. I am saying that it is not clear what justifies Kant’s claim that it must be possible for there to be judgments of beauty as he conceives of them. I suspect the best answer might be that there just are judgments of beauty, or claims to have perceived beauty; and 13 Lines of Grammar. Auburn, March 2009. these judgments struck Kant as having just the inter-subjective force and phenomenological character that one would expect of judgments whose object was the very sense of fit between any empirical concept and the intuition it unifies—a sense of fit that, by his lights, is implicit in every empirical judgment. The ‘subjective universality’ of judgments of beauty struck Kant as just what one would expect of judgments whose object was, in a way, our capacity to make objective judgments überhaupt. Once Kant thought he had found an explanation for judgments of beauty in the working of our cognitive faculties, their possibility turned for him into a necessary possibility. And then things got even better, systematically speaking, since judgments of beauty had traditionally been linked, by empiricists at any rate, and by Kant himself in earlier years, to a feeling of pleasure; and while in the division of the faculties of cognition through concepts understanding and reason relate their representations to objects, in order to acquire concepts of them, the power of judgment is related solely to the subject and does not produce any concepts for itself alone. Likewise, if in the general division of the powers of the mind overall the faculty of cognition as well as the faculty of desire contain an objective relation of representations, so by contrast the feeling of pleasure and displeasure is only the receptivity of a determination of the subject, so that if the power of judgment is to determine anything for itself alone, it could not be anything other than the feeling of pleasure… (FI, 208). And also: An aesthetic judgment in general can… be explicated as that judgment whose predicate can never be cognition (concept of an object) (although it may contain the subjective conditions of cognition in general). In such a judgment the determining ground is sensation. However, there is only one so-called sensation that can never become a concept of an object, and this is the feeling of pleasure and displeasure… Thus an 14 Lines of Grammar. Auburn, March 2009. aesthetic judgment is that whose determining ground lies in sensation that is immediately connected with the feeling of pleasure and displeasure (FI 224, see also Intro 189). And now all we need is to “discover” that judgments of beauty demand of others that they find pleasure in the object just as if it were a property of it, and everything would seem to fall into place—the system would be completed, once and for all. What would be left for us to do is just to patch it here and there, tighten a few loose screws, and otherwise just make good use of it, whenever that is called for. But hold on. A Wittgensteinian aspect, like Kant’s beauty, is also not an objective property—it organizes our visual impression of some perceived object without objectively applying to it. We see the face as courageous, precisely without judging that the face is courageous. We may well call upon others to see courage in the face, or feel that if they cannot see it then there is something in or about that face that they’re missing; but we’ve made no empirical, objective, judgment, or claim. If someone, or something someone has done, just is courageous, then whoever cannot see that is either literally blind or does not know what ‘courage’ means (unless he is missing some pertinent piece of information); but the person who cannot see the face as courageous is, and can conceptually be, neither; and he is not disagreeing with us either. The judgment that someone is courageous commits us to indefinitely many further thoughts and deeds. You cannot, conceptually, truly judge that someone is courageous and not expect him to be at least disposed to act in certain ways, and so without being yourself disposed to act in certain ways in relation to him. By contrast, when you see someone’s face as courageous there is nothing further that you are 15 Lines of Grammar. Auburn, March 2009. committed to do, think, or expect of him. This is yet another way of seeing why the aspect is not a property of the object. ‘Aspects’, Wittgenstein says, ‘do not “teach us about the external world”’.21 He also says that giving voice to an aspect is ‘a reaction in which people are in touch with each other’.22 This combination of ideas seems to me to echo almost precisely Kant’s saying about the judgment of beauty that ‘although it does not connect the predicate… with the concept of the object considered in its entire logical sphere, yet it extends it over the entire sphere of judging persons’ (CJ 215). In seeing an aspect, Wittgenstein says, we ‘bring a concept to what we see’,23 and find the two to fit each other (PI 537); but we do so freely and disinterestedly, in precisely the sense that we needn’t worry about how this experience fits with other experiences or with our goal oriented inquiries and activities. In this sense we can say, as Kant does about the experience of beauty, that here the understanding is in the service of the imagination, rather than vice versa (CJ 242), though I actually believe it would be better—more faithful to the phenomena and philosophically less misleading—to simply say that here our powers of expression are in the service of what we see. In seeing an aspect, I’m proposing, we seem to be doing what we are supposed to do in Kantian judgments of beauty, but far more straightforwardly, phenomenologically speaking: We seem to exercise our sense of fit between intuition and concept apart from the making of any empirical judgment, and therefore unencumbered, but also unguided, by the tie-ups that place any such judgment in relation to indefinitely many others and to the world of action; and we thereby create an opportunity for ourselves to find out, by inviting others to see what we see, whether our sense is indeed common. It turns out that one need not have a feeling of pleasure incorporated into the content of one’s judgment in 16 Lines of Grammar. Auburn, March 2009. order to ensure that the judgment is not objective. Virtually any concept may be applied to a sensibly given object non-objectively, as it were. To see this, we need not investigate our faculties of cognition and their workings. We only need to remind ourselves of a piece of Wittgensteinian grammar. Should we be satisfied with this expansion of Kant’s story? I think not. For I do not think that concept and thing fit together when we see something as something in anything like the ways that concepts and things may plausibly be thought to fit together in other moments of human experience and discourse. To take along Kantian lines the seeing of aspects, or the seeing of beauty, as bringing out in a straightforward manner an element which is basic to human experience as such, is to aestheticize—just as the tradition of western philosophy has tended to intellectualize—our ordinary and normal relation to the things of our world. This is especially true of the ambiguous figures and schematic drawings that Wittgenstein uses in his conceptual investigation of aspects: we encounter them, as Merleau-Ponty importantly notes, in contexts in which they do not ‘belong to a field’ of embodied, significant engagement,24 but rather are ‘artificially cut off’ from it.25 And for this reason Only the ambiguous perceptions emerge as explicit acts: perceptions, that is, to which we ourselves give a significance through the attitude which we take up, or which answer questions which we put to ourselves. They cannot be of any use in the analysis of the perceptual field, since they are extracted from it at the very outset, since they presuppose it, and since we come by them by making use of precisely those set groupings with which we have become familiar in dealing with the world. 26 17 Lines of Grammar. Auburn, March 2009. I think much of this is also true of Wittgensteinian aspects that do not attach to ambiguous figures and are not encountered in artificial contexts. Even when an aspect— the courageousness of a face, say—strikes us in the natural course of everyday experience, our experience is importantly insulated from the rest of our experience. The aspect does not connect with other parts of our experience, does not fit into a field of embodied engagement, in the way that objects and their properties do. Wittgenstein says that in seeing an aspect we bring a concept to what we see; but this is metaphorical, and potentially misleading. For, surely, it is not quite a concept that we bring to what we see. What could that possibly mean from a Wittgensteinian perspective in which a concept is not to be thought of as a mental representation or representational schema, nor as a rule for the unification of intuitions, but rather as something like the word’s fitness or potentiality for employment—its specific reaches and powers? It would be truer to say that what we bring to what we see are images, sensations, bodily attitudes, and moods, that have gotten associated for us with the concept, and really with the word that embodies it. This connects with what Wittgenstein describes as ‘the experience of the meaning of a word’; and again it is important to remember that we do not normally, in the course of everyday discourse, experience the meanings of our words. ‘We talk’, Wittgenstein says, ‘we utter words, and only later get a picture of their life’ (PI, p. 209). Elsewhere he says: ‘Look on the language-game as the primary thing, and on the feelings, etc., as a way of regarding the language-game, an interpretation’ (PI, 654). What we bring to what we see when we see aspects, I’m proposing, are those images, sensations, etc., that, far from underlying the language-game 18 Lines of Grammar. Auburn, March 2009. and being constitutive of the meaning of the words employed in it, have typically gotten associated with it later. In so far as it makes sense at all to speak of application of concepts in the course of ordinary and normal experience, it happens as we talk. In the beginning was the deed, not an act of aesthetic evaluation or contemplation. So say, if you will, that I apply the concept of courage to my son, for example, when I congratulate him for having done something courageous. But if that is what the application of concepts normally comes to, then it is not a matter of bringing images, sensations, embodied attitudes, etc. to sensibly given objects, or to intuitions for that matter. The seeing of aspects, I’m proposing, is parasitic on everyday experience and speech, and so if you will on the application of concepts; but it is importantly discontinuous with it and does not reveal in any straightforward way what’s involved in what may plausibly be thought of as the normal application of concepts. This is one reason why I have on previous occasions resisted the suggestion that there is a continuous version to the dawning of an aspect, and that it somehow characterizes our relation to the things of the world überhaupt—that everything we see is seen under one aspect or another.27 Another reason is that I have not been able to make intelligible to myself the idea that whenever we perceive some more or less familiar object we see it under an aspect; unless that just means that the object is more or less familiar to us, and that we know it for what it is, which is altogether different from what Wittgenstein means by ‘seeing an aspect’. With Wittgenstein, I just cannot make sense of the idea of seeing a knife and fork as a knife and fork (PI, p. 195); and to speak instead of 19 Lines of Grammar. Auburn, March 2009. seeing a proto-knife-and-fork-intuition as a knife and fork, would be to succumb to Sellars’s ‘myth of the given’.28 I come now to my final proposal. Others have already noted the structural analogy between Kant’s ‘Deduction’ of judgments of beauty and Wittgenstein’s saying in PI, 242, that if language is to be a means of communication then there must be agreement not only in definitions, but also in judgments.29 Cavell finds it important that the German word Anscombe translates by ‘agreement’ is ‘übereinstimmung’, which Cavell suggests is better translated by ‘attunement’, and that Wittgenstein speaks of attunement in judgments, not on judgments, which for Cavell means that the attunement in question is an attunement apart from which we would not be communicating at all in uttering our words, and so would be able neither to agree nor to disagree on this or that judgment.30 Cavell’s interpretive point is reinforced by PI 241, which speaks of agreement or attunement ‘not in opinions but in form of life’. Elsewhere Cavell famously characterizes the attunement Wittgenstein relies on in his procedures and at the same time seeks to recover in the face of philosophically induced distortions as ‘a matter of our sharing routes of interest and feeling, modes of response, senses of humor and of significance and of fulfillment, of what is outrageous, of what is similar to what else, what a rebuke, what forgiveness, of when an utterance is an assertion, when an appeal, when an explanation— all the whirl of organism Wittgenstein calls “forms of life”’.31 Both Kant and Cavell’s Wittgenstein, then, are concerned with a level of agreement or attunement between us apart from which it would not have been possible for us to either agree or disagree with each other on empirical judgments—for we would 20 Lines of Grammar. Auburn, March 2009. not have agreed in the meanings of our words, or, if you will, in our concepts. But if my discussion thus far has been on the right track, then there is a fundamental difference between what the agreement Kant has in mind comes to and what the agreement Wittgenstein has in mind comes to. In Kant, as we saw, speech is pictured as grounded in, and expressive of, acts of unifying intuitions by means of concepts, and vice versa; and the agreement he has in mind is agreement in what strikes us as good or satisfying or unforced fit between concept and intuition. Speech, for Kant, is thought of as parasitic on acts of judgment that are not essentially linguistic. In Wittgenstein, by contrast, and putting it extremely roughly, concepts and things come together through the medium of speech. To speak, for him, is to enter one’s words into a humanly significant situation, real or imagined, to make thereby some more or less definite and more or less significant difference, and to become responsible for having made that difference; and the meaning of a word—and in particular the meaning of a philosophically troublesome word—is best thought of as its suitability, or potentiality, given its history, for being used to make specific differences under suitable conditions. In what Wittgenstein likes to refer to as ‘doing philosophy’, we tend to get entangled because we rely on our words to mean something clear even apart from our using them to make some particular difference, or point. We wish, as Cavell puts it, ‘to speak without the commitments speech exacts’.32 The ordinary language philosopher’s appeal to the ordinary and normal use of our philosophically troublesome words is meant as a corrective for this particular form of philosophical flight or fantasy, and as pointing the way out of the conceptual entanglements it tends to lead us to. 21 Lines of Grammar. Auburn, March 2009. This means that the philosophical appeal to ‘what we should say when, and so what and why we should mean by it’ has just the place within Wittgenstein’s ‘vision of language’ that judgments of beauty are supposed to have within Kant’s system. Both are supposed to search for and bring out a level of attunement between us that tends to only be implicit in ordinary and normal discourse. According to Kant, the two grammatical features of judgments of beauty ‘abstracted from their content’ (CJ 281) are the claim for universal agreement (CJ §32), and the lack of any established procedure for proving or settling the correctness of our judgment (CJ §33). These two features, Cavell has proposed, also characterize the appeal to ordinary language; and their combination makes for the ‘air of dogmatism’ that he acknowledges as characteristic of that appeal. 33 But these are precisely the features one would expect of claims that had as their object, as it were, a level of agreement or attunement between us apart from which we would not have been able to prove or settle anything objectively, nor, indeed, to truly speak to and understand one another. Kant’s ‘subjective universality’ is the sound of one’s spade turning against one’s bedrock, however we picture that bedrock to ourselves when we do philosophy. Notes 1 ‘What’s the Point of Seeing Aspects?’, Philosophical Investigations, 23: 97-122, 2000. 22 Lines of Grammar. Auburn, March 2009. 2 ‘Kant’s Principle of Purposiveness, and the Missing Point of (Aesthetic) Judgments’, Kantian Review, 10: 1-32, 2005. 3 Kant on Beauty and Biology, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007. See also, Ido Geiger, "Is the Assumption of a Systematic Whole of Empirical Concepts a Necessary Condition of Knowledge?" Kant-Studien 94 (2003): 273-298. 4 Beauty and Biology, 1. 5 Ibid, 52. 6 Ibid, 14. 7 See Jäsche Logic, §6. 8 Kant’s Theory of Form, Yale University Press, 1982, 113. 9 I also think that certain moral judgments—namely, those expressive of what Cavell has called ‘Emersonian perfectionism’—may aptly be said to partake in the grammar of Kantian judgment of beauty. 10 I discuss these issues in ‘Seeing Aspects and Philosophical Difficulty’, forthcoming in Handbook on the Philosophy of Wittgenstein, Marie McGinn (ed.), Oxford University Press, 2009. 11 See, for example, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, in Basic Writings, Alfred Hofstadter (tr.), David Farell Krell (ed.), Harper Collins, 1993, p. 161. 12 See Lectures and Conversations on Aesthetics, psychology and Religious Belief, Cyril Barrett (ed.), Blackwell, 1989, 37. 13 See Lectures and Conversations, 3. 14 Guyer and Wood translate ‘veranlasst’ by ‘occasions’, and thereby cover up the phenomenological feature of being goaded, called upon, by the beautiful thing—letting it draw words from us—that Kant’s word invokes. 15 Another point Wittgenstein makes is that even if, implausibly, we did find something—an experience— that occurs every time we mean, or see, or understand… something, there would still be no reason for supposing that this something is what meaning, or seeing, or understanding… consisted in. I explore these themes in Wittgenstein in ‘Seeing Aspects and Philosophical Difficulty’. 16 ‘The Availability of Wittgenstein’s Later Philosophy’, in Must We Mean What We Say, 64-5. 23 Lines of Grammar. Auburn, March 2009. 17 One of the best illustrations of this procedure is Cavell’s discussion of the grammar of pain in The Claim of Reason (Oxford University Press, 1979), 78. 18 What is Called Thinking, 19. 19 Eye opening, with respect to Kant’s faith in, and craving for, philosophical system, is his well-known letter to Reinhold from December of 1787. 20 A132-4/B171-3 21 Remarks of the Philosophy of Psychology, Vol. I, 899. 22 Ibid, 874. 23 Ibid, 961. 24 Phenomenology of Perception, 216. 25 Ibid, 279. 26 Ibid, 281. 27 For two versions of the proposal that all seeing is seeing as, or the seeing of aspects, see Strawson, ‘Imagination and Perception’ (in Kant on Pure Reason, Ralph Walker (ed.), Oxford University Press, 1982); and Stephen Mulhall, On Being in the World: Wittgenstein and Heidegger on Seeing Aspects (Routledge, 1990). 28 Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind (Harvard, 1997). 29 See David Bell, ‘The Art of Judgment’, Mind 96, No. 382 (Apr., 1987), pp. 221-244; and Anthony Savile, Kantian Aesthetics Pursued (Edinburgh, 1993), pp. 35-7. 30 In ‘Knowing and Acknowledging Cavell makes essentially the same point: ‘[M]y interest in finding what I would say (in a way that is relevant to philosophizing) is not my interest in preserving my beliefs… My interest, it could be said, lies in finding out what my beliefs mean, and learning the particular ground they occupy’ (in Must We Mean What We Say, 241). 31 ‘The Availability of Wittgenstein’s Later Philosophy’, in Must We Mean What We Say?, 52. 32 Ibid, p. 215. 33 ‘Aesthetic Problems’, 96. 24