RTI - Home/Introduction

advertisement

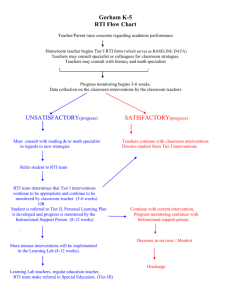

RTI Literature Review By: Jennifer Deering EDU 744: Meeting Student Literacy Challenges University of New England July 14, 2010 Response to Intervention, or RTI for short, is a direct result of changes made to the Individuals With Disabilities Act (IDEA) in 2004. The piece of legislation concerning RTI allows schools to use up to 15% of their special education budget for regular education interventions (Johnston, 602). The purpose of RTI is two-fold: to provide early intervention for those students at risk for failure, and to provide valid procedures to identify students with reading disabilities (Gersten & Dimino, 2006). According to an article found on the site www.recognitionandresponse.org, a partner of the National Center For Learning Disabilities, Inc., some data is beginning to emerge touting the effectiveness of RTI: A research synthesis conducted on 14 studies concluded that there is an emerging body of empirical evidence to support claims of the effectiveness of RTI. The findings suggested that RTI is effective for identifying children at risk for learning disabilities and for providing specialized interventions, either to ameliorate or to prevent the occurrence of learning disabilities (“Supporting Evidence,” 2010). While it may be too early for large, longitudinal studies, the early research is promising; RTI appears to be an effective means of intervening with children at risk for failure and of reducing the number of overall students labeled as learning disabled. Prior to RTI, schools used the IQ-discrepancy model to identify students with learning disabilities. With this model, popular since the late 1970's, schools administered IQ testing to those students who appeared to be struggling. The test scores were then compared with student achievement; if a significant gap existed, the child was considered learning disabled (Mesmer & Mesmer, 2008). The problems with this model were plenty. First, it was very common to wait until a child was at the end of second grade or beginning of third grade before deciding that there was cause for concern regarding a student's reading development; teachers felt it was more humane to wait that long before saddling a child with a special education label (Gersten & Dimino, 2006). This was referred to as the “waiting to fail” problem. Ironically, studies have shown that children who are not reading on grade level by the end of first grade will continue to struggle with reading throughout their schooling, so this method was not doing those children any favors. Another problem was that interventions given to the teacher were done so with only anecdotal information from the teacher; there was no hard data considered prior to special education testing. The interventions were also made for the individual student; they were not something that was going to elevate a teacher's skill in teaching reading or writing to the next level (Gersten & Dimino, 2006). Furthermore, the IQ discrepancy model did not take into consideration other factors that could be hindering a child's learning, such as home life or exposure to quality education. With this model, the percentage of children identified with special needs rose at astronomical rates (Mesmer & Mesmer, 2008). The model presumed that the slow achievement of “socalled children labeled as learning disabled” was a true reflection of disability when, many times, it actually simply reflected poor teaching (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2006). Obviously, a change needed to occur. The IDEA law of 2004 allows schools to choose whether or not to use the IQ discrepancy model or the RTI model. When using the RTI model, the law states that a learning disability may be present if a student is not performing up to grade level standards, despite intensive, research-based interventions (Mesmer & Mesmer, 2008). RTI is primarily for the purpose of providing those intensive, researchbased early interventions in order to prevent later reading failure (Gersten & Dimino, 2006). It calls for “the evaluation of a performance relative to a defined academic standard” (Mesmer & Mesmer, 2008). Interventions, based on those evaluations, are then put into place. The point is, as mentioned earlier, to get children reading and writing on grade level by the end of first grade. In their paper, Gersten and Dimino (2006) cite a study by Stanovich (2006) that notes proficient readers will continue to build vocabulary and fluency through reading, where the struggling readers will avoid reading at all costs, thus lengthening the gap between the two. How can RTI help? RTI works by identifying students who are failing to meet grade level benchmarks through frequent assessments at least 3 times a year. It is, essentially, progress monitoring. It is also, usually, a three-tiered model, with each tier being more intense than the last. Fuchs and Fuchs (2006) state that increasing intensity is achieved with the following: “using more teacher-centered, systematic and explicit instruction; conducting it more frequently; adding to its duration; creating smaller and more homogenous student groupings; or relying on instructors with greater expertise.” They go on to explain two manners of providing the above instruction. One is through problem-solving, which requires a teacher to use an assessment of their choice to monitor growth. When there is an absence of growth, they will then try research-based interventions that are individualized for the children they are working with. At each tier, the process is the same: you determine the size of the problem, look for causes, design goal-oriented interventions, adjust the interventions as needed, evaluate once again, and plan what to do next. An effort is made to personalize the assessments and interventions, making this the preferred method for RTI among schools. The second manner of providing RTI is one which researchers most prefer. It is the standard treatment protocol method. The problem-solving approach varies from child to child, but the standard treatment protocol does not. There are both standardized testing and interventions. If a child shows progress at tier 1, they are assumed to have no disability and are sent back for regular classroom instruction. The same occurs if progress is made in tier 2. If there is no progress, than a disability is assumed (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2006). Mesmer and Mesmer (2008), in their article entitled “Response to Intervention (RTI): What Teachers of Reading Need to Know,” explained RTI using five steps, instead of the three tiers. In step one, all children are assessed on the basic literacy skills at least three times a year. Each child's score is then compared to the expected benchmark for that grade level. Those children falling below the benchmark are set to receive researched-based interventions, which is step two. Step three is the progress monitoring piece, where the child is being watched carefully for signs of progress. In step four, those children not making progress with small group interventions are then moved to individualized, intense, and targeted interventions. The final step (5) is the process of deciding whether or not a child might qualify for special education services. Though Mesmer and Mesmer have five steps instead of the three tiers mentioned in other studies, the process is essentially the same. There are still some problems to be ironed out with the RTI protocol. The first problem is the training of teachers or specialists who will be delivering the interventions. When RTI was researched for effectiveness, the people delivering the interventions were highly trained research personnel or teachers who received support and guidance from the researchers. In reality, teachers come with various degrees of knowledge of how best to instruct students in reading and writing and districts can only provide as much training as budgets allow. Whether or not teachers are able to effectively deliver the intense, research-based instruction is a concern. Another potential issue is the viewing of benchmarks on standardized tests as the final say. In actuality, they are merely guidelines for students, so schools need to be careful to use them accordingly (Gersten & Dimino, 2006). Because RTI is considered most important for early intervention, it is possible to over-identify students who might require special interventions. The younger the children, the less valid an assessment is, according to Gersten and Dimino (2006). By waiting longer, the evaluations are more accurate, but you miss the window for early intervention by the end of first grade. Yet another possible problem with RTI is the fact that some children, though they may make progress with the RTI interventions, are not able to work in a mainstream classroom; they may, in fact, have a disability, but it is not picked up because they show adequate progress with the interventions. As a result, they end of falling back behind their peers once the interventions are removed (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2006). Finally, there are concerns surrounding assessments used. First, most of the assessments used for RTI measure phonological awareness, letter/sound knowledge, and decoding. However, these are just pieces of the puzzle that make up a proficient reader. They also need to have good vocabulary skills, comprehension, and fluency, but there are yet to be developed powerful screenings and assessments that measure those skills for the purpose of RTI (Mesmer & Mesmer, 2008). Second, there is a concern about the fact that practitioners rely on an assortment of assessments and procedures (instead of a set list of both), which could lead to unreliability of the diagnosis of reading disability, which is one of the concerns surrounding the use of the IQ discrepancy model (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2006). RTI often leads to intensive work with struggling learners as early as kindergarten, in an effort to help them read on grade level by the end of first grade. It is designed to work without all the hurdles one must cross in order to make a special education referral, while at the same time reducing the number of children who ultimately wind up in special education. What has been found through RTI is that children were inappropriately placed in special education with the IQ discrepancy model; they were not learning disabled, but more often than not had simply received inappropriate instruction (Gersten & Dimino, 2006). The effectiveness of special education has been “variable at best” (Mesmer & Mesmer, 2008), and RTI has started to show that students benefit immediately from the progress monitoring and intense research-based interventions that are the cornerstone of that model. References: Anonymous. (2010). Recognition and Response in Action. Retrieved July 12, 2010, www.recognitionandresponse.org/content/view/84/95/. Fuchs, D., & Fuchs, L. S. (2006). Introduction to Response to Intervention: What, Why, and How is it Valid?. Reading Research Quarterly, 41(1), 93-99. Gersten, R., & Dimino, J. (2006). RTI (Response to Intervention): Rethinking Special Education For Students with Reading Difficulties (yet again). Reading Research Quarterly, 41(1), 99-108. Johnston, P. (2010). An Instructional Framework for RTI. The Reading Teacher 63(7), 602-604. Mesmer, E. M., & Mesmer, H. A. (2008). Response to Intervention (RTI): What Teachers of Reading Need to Know. The Reading Teacher 62(4), 280-290.