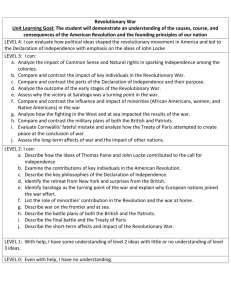

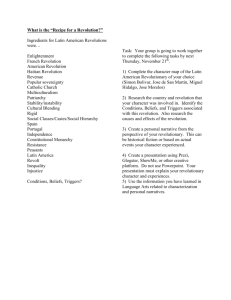

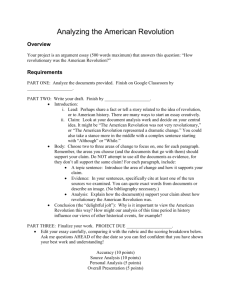

Revolutions, Passions, and Modern Politics

advertisement