ClimateBasics

advertisement

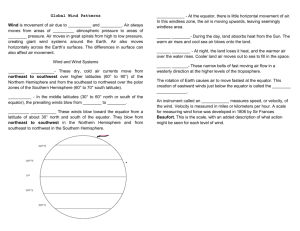

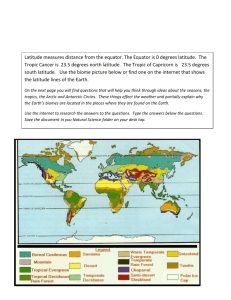

CLIMATE BASICS Climate is average weather that takes into account seasonal variations. The two major characteristics of climate are temperature and precipitation. Climate affects arability (whether or not soil can be productively farmed) and accessibility. Farming is difficult in areas that are too wet, too dry, or too cold. Transportation can also be difficult in areas that are too wet, too dry, too hot, or too cold. Temperature The earth is heated by the sun. Areas that have more hours of sunlight and more intense exposure are warmer than areas with less sunlight and weaker exposure. Look at the Surface Temperature Map on Plate 57 of the Geography Coloring Book. Notice that areas around the Equator are always hot. Most of the polar areas are not shown on this map, but you can see that the center of Antarctica is always cold. (The island northeast of Canada, whose interior is always cold, is Greenland.) The difference is because much more solar energy is directed at Equatorial areas than polar areas. Therefore, we can see that latitude is the chief determinant of an area’s temperature. Notice that outside of polar and Equatorial areas, the temperature changes depending on the seasons. Latitude and Longitude Geographers use latitude and longitude to determine the absolute location of a place. Lines of latitude run east west and lines of longitude run north to south. Both latitude and longitude are measured in degrees, which is a measure of their angular distance from a reference line. With latitude, the reference line is the Equator; with longitude, the reference line is the Prime Meridian. There are 180 degrees of latitude in all, 90 in the Northern Hemisphere and 90 in the Southern Hemisphere. There are 360 degrees of longitude in all, 180 in the Eastern Hemisphere and 180 in the Western Hemisphere. Read page vi of Goode’s World Atlas for more information about “Important Characteristics of the Global Grid.” The Seasons What accounts for the seasonal changes in temperature found in the middle latitudes? The most basic answer is that the farther a place is from the Equator, the more the amount of incoming solar radiation varies from season to season. This variation occurs because the earth tilts on its axis. The angle of the tilt is 23.5° away from a line perpendicular to the axis of rotation. As the earth rotates around the sun, the northern and southern hemispheres change their orientation to it. The figure at right shows the seasons with respect to the northern hemisphere. On the Summer Solstice (June 20/21), the northern hemisphere is tilted most fully toward the sun. This is the day when the northern hemisphere receives the most incoming solar radiation. At noon, the sun’s rays are ever directly over the Tropic of Cancer (23.5°N). This is the farthest north that the sun’s rays are directly overhead. When the sun’s rays are directly overhead, they are more intense. This is the “longest day” of the Northern Hemisphere – that is, the hours of daylight are longest and nights are shorter. (Conversely, this is the shortest day of the southern hemisphere.) The difference in the amount of daylight varies by distance from the Equator. At the Equator, the length of daylight varies by less than 3 seconds from summer to winter. At the Poles, however, the length of daylight varies by six months! (The North Pole’s day starts on March 20/21 and ends on September 22/23, when its night begins.) Three months after the Summer Solstice, as the earth continues its path about the sun, the noon-day sun is over the Equator. This is the Autumnal/Fall Equinox (September 22/23). Everywhere on Earth experiences 12 hours of sunlight and 12 hours of darkness – even the Poles. Three months later, on the Winter Solstice (December 22/23) the noon-day sun is over the Tropic of Capricorn (23.5°S). This is the farthest south that the sun’s rays are ever directly overhead. The northern hemisphere is tilted away from the sun. This is the shortest day of the northern hemisphere and the sun’s rays are weakest. This is the day in the northern hemisphere with the least incoming solar radiation. The opposite is true for the southern hemisphere. Three months later, the noon-day sun is once again over the Equator. This is the Vernal/Spring Equinox (March 20/21) and both hemispheres experience 12 hours of light and 12 hours of darkness. You might wonder why the hottest day of the year of the northern hemisphere isn’t the Summer Solstice and the coldest day of the year the Winter Solstice. This is because the sun’s rays do not directly heat the earth’s atmosphere. Instead, incoming solar radiation passes through the atmosphere and warms the metal-rich crust of the earth and, more slowly, the oceans. As the earth itself warms, it radiates energy back into the atmosphere, warming it. So, typically, July and August are hotter than June and January and February are colder than December. Latitude Zones Geographers divide the earth into three general latitudinal belts: low, middle and high. Their names come from the size of their latitude numbers. The low latitudes are those with the lowest degrees. The Equator is zero degrees, so it is the lowest latitude. This latitude belt extends from the Tropic of Cancer (23.5°N) to the Tropic of Capricorn (23.5°S). The low latitudes receive the most incoming solar radiation year round and therefore have warm year-round temperatures. The high latitudes are those with the highest numbers. The Poles are ninety degrees, so they have the highest latitudes. There are two high latitude belts. In the north, the high latitude belt lies above the Arctic Circle (66.5°N); in the south, the high latitude belt lies below the Antarctic Circle (66.5°S). The high latitudes receive the least incoming solar radiation year round and therefore have cold year-round temperatures. The Circles, both located at 66.5°. (It might help you remember that this is equal to 90° minus 23.5°.) Areas above the circles experience at least 24 hours of darkness and 24 hours of light one day per year. Between the low and the high latitudes lie the middle latitudes. They extend from the Tropic of Cancer to the Arctic Circle in the north and from the Tropic of Capricorn to the Antarctic Circle in the south. The middle latitudes have seasonal changes in temperature, with hotter summers and cooler winters. Other Factors Affecting Temperature While latitude has the biggest effect on temperature, other factors such as altitude and proximity to major water bodies and prevailing wind conditions, can also have significant effects. Read more about these in the text accompanying Plate 57 in the Coloring Book. Global Circulation of Air. Before we can consider precipitation, we need to discuss the global circulation of air. Do you know why wind blows? There are two basic reasons. The first is that the earth rotates on its axis – one revolution every 24 hours. The earth turns under the atmosphere. Even though we are moving with the earth, it seems like the air is moving. This is much like when we’re sitting in a car and it seems like trees and other stationary objects are moving instead of the car. Air Pressure The second reason that wind blows is because of temperature differences on earth. These temperature differences cause differences in air pressure. Air pressure refers to the pressure that a column of air exerts against the surface of the earth. As warm air expands, it becomes lighter and rises. This is the principle that allows hot air balloons to float up and away. A column of warm air is light and rising so it exerts low pressure against the surface of the earth. When cold air condenses, it becomes heavier and sinks. Cold air is heavy and exerts higher pressure against the earth’s surface. Wind always moves from high pressure to low pressure across the surface of the earth . Logically, areas that are the warmest should have the lowest air pressure and areas that are the coldest should have the highest pressure. Therefore, we should expect there to be a strong low pressure cell along the Equator and high pressure cells at the poles. Look at the Zones of Precipitation figure at the lower right-hand corner of page 21 in Goode’s World Atlas. In the Zones of Precipitation figure, arrows pointing up toward the atmosphere represent low-pressure areas while arrows pointing toward the earth represent high-pressure areas. Near the Equator are the doldrums or the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). The air along the Equator is rapidly heated causing it to rise quickly into the atmosphere. The doldrums receive lots of convectional precipitation. Notice that the low-pressure cell shifts slightly with the seasons. In the Northern Hemisphere summer, it is slightly north of the Equator; in the winter it is slightly south. As expected, polar areas are characterized by high pressure. The earth is too large to allow air to move directly from the poles to the Equator, so there are intermediate high and low pressure cells. Look back at the low-pressure cell along the Equator. When the air rises into the upper atmosphere it chills and becomes heavier. It tries to sink, but cannot sink directly down because of the strong flow of the convectional current. Instead, like a fountain of water, it falls to the sides. It sinks down in an area around the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn. Notice that in the Northern Hemisphere summer, the high pressure cells are north of Tropics – about 40°N and 20°S. The high-pressure cells follow the sun to the south. In the Northern Hemisphere winter, the high-pressure cells are south of the Tropics – about 20°N and 40°S. Cold heavy air sinks down at the poles and then sweeps across the earth’s surface. As the air moves away from the poles, it warms. Between 50° and 60° there is another low pressure belt. This is considerably weaker than the low pressure belt found at the Equator, but it still influences global wind patterns. Like the other pressure belts, these low-pressure belts shift north in the summer and south in the summer. You can get another view of this in Plate 58 of The Geography Coloring Book. Low pressure and high pressure are not directly indicated on this map, but you can infer them from the arrows because wind moves from high to low pressure. The arrows on Plate 58 represent prevailing wind direction. They point toward low pressure and away from high pressure. Prevailing Winds Remember that wind always blows from high pressure to low pressure. However, because of the rotation of the Earth, wind rotates in a clockwise direction in the Northern Hemisphere and a counter-clockwise direction in the Southern Hemisphere. In the low latitudes, wind bends from east to west. By convention, winds are named for the direction of their origin so the prevailing winds in the low latitudes are easterlies. In the middle latitudes, wind bends from west to east. The prevailing winds in the middle latitudes are westerlies. In the high latitudes, wind bends from east to west. Precipitation Precipitation is water that falls from the sky whether it is in the form of rain, snow, sleet or hail. ? (See Plate 56 of The Geography Coloring Book for more information about annual rainfall.) Precipitation occurs when a waterbearing air mass lifts, chills in the higher atmosphere, and condenses. When the air mass condenses, it is like squeezing the moisture out of a sponge. There are three general types of precipitation – convectional, orographic, and frontal, named for the mechanism that causes the air to rise. Convectional Precipitation The first is convectional precipitation, where air rises because it is rapidly heated. When it rises, it chills, squeezing the moisture out. Convectional precipitation occurs as brief afternoon showers where and when it is hot. It occurs in the low latitudes year round and in the lower middle latitudes in the summer. There is an excerpt from the BBC Archive on YouTube at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RkgThul2El8. Orographic Precipitation Orographic precipitation occurs when an air mass hits a sizable topographic barrier. It can’t go around the barrier because it is too large, so it has to go up and over. When the air mass rises, it chills and squeezes out moisture. Orographic precipitation occurs where there are mountains. Mountains close to oceans often get lots of precipitation. The side of the mountain that the wind first hits is called the windward side. As the air rises on the windward side, it chills and clouds form. If there is enough moisture, precipitation will occur. The other side of the mountain is the lee side. On this side, the heavy cold air sinks back down again. As it sinks, it warms. As it warms it expands. It is like releasing the sponge we talked about earlier. The lee side is drier. Beyond the topographic feature is the rain shadow. This is a dry area because the air mass has lost its moisture and there isn’t anything to force it back up again. There is a nice video of orographic precipitation on YouTube at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GJR893xiTr0. Question: In the low latitude belt, on which side of the topographic barrier is the rain shadow? Why? Frontal Precipitation Frontal precipitation occurs when warm and cold air masses collide. The cold air mass will be heavier than the warm air mass. Regardless of whether one or both of the air masses is moving, the warm air mass will be pushed upward. When it rises, it will chill and squeeze out moisture. Frontal precipitation occurs in areas where and when temperatures vary – the middle latitudes, particularly in the spring and fall. Precipitation Patterns Worldwide, the average precipitation is about 35 inches. That doesn’t mean much because some places receive over 100 inches of rainfall every year and other places receive no rain at all. Look at the Annual Precipitation and Ocean Currents map on pages 20 and 21 of the Goode’s World Atlas. The areas that are dark blue receive over 80 inches of rainfall annually. Notice that most these areas of highest precipitation lie on or near the Equator, where low pressure prevails and convectional precipitation occurs year round. Mountainous coastal areas where orographic precipitation is active also receive high levels of precipitation. Arid areas receive less than ten inches of rainfall annually. They are represented in tan on the map. Can you perceive any pattern in the distribution of these arid areas? Arid areas tend to exhibit one or more of the following characteristics: location in high-pressure areas; extremely cold temperatures, locations far from water, locations in a rain shadow, coastal locations where cold water currents are adjacent to warm landmasses. High-pressure areas and cold temperatures are linked. Polar areas are cold, leading to high pressures. There are also high-pressure bands that are not linked to surface cold temperatures. These shift between 20°and 40° north and south of the Equator. Here, air masses tend to be dry and they cannot rise. Notice the low precipitation levels in polar areas and near the Tropics. As you move away from the Equator, interior areas are drier than coastal areas because the air masses that move through them tend to be drier. Even if uplift occurs, there will be little moisture to squeeze out. Air masses in rain shadows are also dry, having lost their moisture on the windward side of the mountain. Warm coastal areas off cold currents are also related to dry air masses. In this case, air traveling over cold currents chills and squeezes, losing its moisture over the water. When the air hits the land, it begins to warm and to expand, so the land is dry. Coastal deserts due to cold water are always found on the west coasts of warm land masses. This is because ocean currents, like air currents, circulate clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and counter-clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere. Look back at the map. The blue arrows represent cold water currents and red arrows represent warm currents. Blue currents start in the high latitudes and circulate toward the Equator – always on the west side.