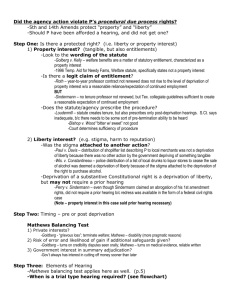

Administrative Law – Pierce – Fall 2008

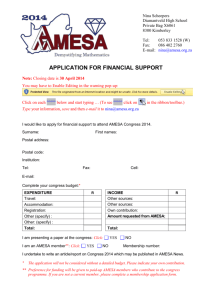

advertisement