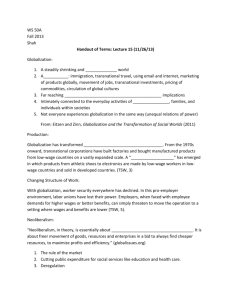

IPSA.Parker Brenda.Geog Gender and Globalization

advertisement

Updated 2/8/2004 GEOGRAPHY 302: GLOBALIZATION AND GENDER COURSE SYLLABUS TIME AND LOCATION Spring Semester 2004 Tuesdays, 6:30 – 9:00 p.m. 1651 Humanities Building INSTRUCTOR Brenda Parker Office Hours: Monday 1:30 – 3:00 417 Science Hall Tuesday 4:30 – 6:00 bkparker@wisc.edu By Appointment (608) 239-4517 OVERVIEW In this course we will discuss geographical and feminist analyses of globalization processes. This means looking not only at transnational corporations and global trade policies, but also at households and identities. In particular, we will focus on gender roles in the global political economy. For example, we will analyze growing feminized economies of maids, nannies, and other service workers. In these economies, race and ethnicity figure prominently. We will also examine feminist transnational activism, and changing political and family roles for women and men. In this way, we will consider how women and men's experiences with globalization involve both exploitation and empowerment, and how various spatial and social inequalities intersect with gender relations. Through case studies, students will be encouraged to critically examine unique and changing geographies of gender and globalization. COURSE OBJECTIVES: By the end of this course, students should: Be familiar with geographical approaches to analyzing globalization, including privileged sites and subjects of analysis; Be able to articulate feminist analyses of global political economy; Understand ways in which globalization and gender relations are mutually constituted Be aware of the multiple scales involved in globalization, including the body, household, and nation-state; and Be able to identify ways that globalization produces opportunities for exploitation and empowerment for men and women. COURSE DESIGN We will meet once a week for 2.5 hours. Each class will consist of a lecture period (70 minutes), a short break (10 minutes), and a discussion period (70 minutes). Periodically the discussion period will be substituted by a movie or other group activity. 1 Updated 2/8/2004 In order to facilitate discussion, the class will be broken into small groups of six to eight students at the beginning of the semester. Discussions will take place in these small groups, which will remain constant throughout the semester. Each student will have the opportunity to lead a small group discussion during the semester. Discussions will revolve around case study readings and key themes from lectures. Your full participation as both a discussion leader and a discussion participant will be expected during the semester, and will help make this an interesting and provocative class for all students. I encourage lively, honest, but respectful debate and discussion, as it contributes to the learning environment in the classroom. GRADING AND ATTENDANCE POLICY Participation (and therefore attendance) will be an important part of this class. If you have more than one unexcused absence, your grade will drop by .5. If you miss a day when you are supposed to act as facilitator or recorder, this will also affect your overall grade. Small group discussions and weekly assignments 50% Final Paper 50% ASSIGNMENTS Each week there will be a short assignment. Most commonly, you will be asked to come up with 5 critical questions for discussion based on the readings. All assignments must be typed and turned in on the due date. I will not accept late or hand-written assignments. Other weeks, I will ask you to write a short essay, locate a current article or media clip for discussion, or write a book review. These activities are designed to help you keep up with the readings, to extend your learning, to facilitate interesting class discussions, and to let me know how you are engaging with the course materials. These weekly assignments, along with your participation and facilitation in your small groups, will comprise 50% of your grade. The other 50% of your grade will be based on a final term paper (15-20 pages), due on May 11th. For your final research project, you may choose between one of the following options. 1.) Research a ‘feminized’ economy in one region or country in the world. 2.) Research a complex non-profit organization or activist movement that is challenging negative outcomes and inequalities associated with globalization. 3.) Research a paper topic of your own selection related to themes of gender and globalization. To pursue this option, prepare a 200-400 word typed description of the paper topic for my approval Further details about the paper requirements and grading criteria are attached. There is no final exam for this course. 2 Updated 2/8/2004 TEXT BOOKS AND READINGS There are books and reserved readings for this course. Books can be purchased at A Room of One’s Own Feminist Bookstore, 307 W. Johnson Street. There are three books available for purchase: Ehrenreich, B and A.R. Hochschild, eds. 2003. Global Woman: Nannies, Maids and Sex Workers in the New Economy. New York: Metropolitan Books. Naples, N. and M. Desai, eds. 2002. Women’s Activism and Globalization: Linking Local Struggles and Transnational Politics. London: Routledge. Seagar, J. 2003. The Penguin Atlas of Women in the World. Penguin Press (Recommended) One copy of each of these books will also be placed on reserve in College Library Reserve collection, located on the 1st floor of College Library in the Helen C. White Building. All other course readings will be placed on E-reserve with College Library, and two hard copies of the readings will be placed on reserve in the Geography Library. The Geography Library is on the second floor of Science Hall. 3 Updated 2/8/2004 COURSE SCHEDULE AND READINGS January 26th Globalization: Fact, Fiction, and Fantasy This class will focus on the dominant approaches to globalization within economic geography. We will explore some of the dynamics of contemporary political-economic globalization, and try to sift through some of the facts and fantasies of this phenomenon. We will consider primary measures of globalization, the media ‘hype’ around globalization, and the differences between internationalization and globalization. Dicken, P. 1997. Global Shift, 19-70. Dicken, P., Peck, J. and Tickell, A. 1997. Unpacking the Global. In Lee, R. and Wills, ed. Geographies of Economies. London: Arnold Press Brah, A. 2002. Global mobilities, local predicaments: Globalization and the Critical Imagination. Feminist Review 70: 33-45. Assignment: Find a media article, editorial, or advertisement that relates to economic globalization. Write a two or three paragraph commentary on the portrayal of globalization offered in the piece you have selected, and how it corresponds to or contradicts the ideas about globalization provided in the readings for this week. Be prepared to discuss your commentary in a small group. February 3rd Gender Relations: Setting the Context In this class we will first discuss basic theories of gender relations, including the relationship between gender and sex and constructions of masculinity and femininity. We will examine how gender binaries that privilege the masculine over the feminine (and therefore men over women) permeate global society, although in unique ways. I will discuss the importance of gender roles, and review dominant conceptions of what is ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine.’ In this lecture, we will emphasize gender as a crucial axis of power, but one that is intersected by other social dynamics such as ethnicity, a point that will arise in the case studies we explore this semester. Connell, R.W. 2002. Gender, 1-11, 29-52, and 96-114. ‘Gendered Divisions of Power.’ In Global Gender Issues, ed. V. Spike Peterson and Anne Sisson Runyan, 69-111. February 10th Reconsidering Globalization: Feminist Perspectives In this class we will attempt to weave together concepts from the previous two lectures. In doing so, we will emphasize feminist analyses of globalization. These feminist interpretations of globalization broaden the scope offered by traditional economic geography. For example, feminists have argued that informal economic activity, feminized economies such as the maid trade and sex trade, and unpaid work in the home comprise a major part of the globalization story, but are too rarely discussed in globalization texts. Feminists have also emphasized the uneven and gendered impact of 4 Updated 2/8/2004 economic globalization, and called attention to the various scales at which globalization operates—including the body, household, and nation-state. These feminist interpretations of globalization offer a general framework for this class, and will allow us to take a more comprehensive view of globalization that does not necessarily separate ‘work’ from ‘life,’ or ‘reproduction’ from ‘production’ but considers them together. Waring, M. 2002. Counting for Something! Recognizing Women’s Contributions to the Global Economy through Alternative Accounting Systems. Gender and Development, 35-43. Nagar, R., et al. 2002. Locating globalization: Feminist (re)readings of the subjects and spaces of globalization. Economic Geography 78.3, 257-284. Moghadam, V. 1998. ‘Gender and the Global Economy’ In Revisioning Gender, ed. M. Marx Ferree, J. Lorber, and B. Hess. Hooper, C. 2002. Masculinities in Transition. In Gender and Global Restructuring, 59-73 Assignment: Prepare 5 typed questions that demonstrate you have completed all of the readings for this week. These questions should draw out opinions and ideas of classmates, and relate to the academic content of the readings and the course. February 17th Global Movement: Trade Politics and Problems Increases in global trade are often used to affirm the extent of economic globalization in mainstream economic analysis. In this class we will look at the historical trajectory of global trade and the governance structures that regulate them, beginning with GATT and moving on to the World Trade Organization. We will look at the inequalities that are exacerbated under free trade. We will also discuss the notion of ‘open trade’ as a foundational aspect of development policies, and structural adjustment measures that have been required of developing countries. In particular, we will consider the impact of these structural adjustment policies upon the lives of women and resistance by feminist and other activists.. Hoekman, B and M. Kostecki. 2002. Trading System in Perspective. In The Political Economy of the World Trading System, 10-46. Bussumtwi-Sam, J. 2000. International Financial Institutions, International Capital Flows, and Financial Liberalization in Developing Countries. In Globalization and its Discontents, ed. McBride and Wiseman, Pearson, R. 2003. Feminist Responses to Economic Globalization. Gender and Development 11: 25-34. Desai, M. 2002. Transnational Solidarity: Women’s Agency, Structural Adjustment, and Globalization, in Women’s Activism and Globalization, 15-33. 5 Updated 2/8/2004 Navarro, S.A. 2002. Las Mujeres Invisibles, In Women’s Activism and Globalization, 83-98. (These final two readings are from required course book. The book is available on reserve in College Library, 1st Floor) Assignment: Prepare 5 typed questions that demonstrate you have completed all of the readings for this week. These questions should draw out opinions and ideas of classmates, and relate to the academic content of the readings and the course. February 24th Global Movement: New lives, New Inequalities, and New families? Building upon last week’s lecture on the movement of traded goods, this week we will discuss the movement of people and labor, which involves a number of complicated motivations and inequalities. In this lecture we will discuss some general patterns of migration under globalization. We will consider reasons given by men and women for migrating to different countries, and how these reasons are intimately tied not just to inequality and economics, but also to families. We will look generally at the kind of work opportunities available to migrants, and to the impact of migration on gender relations, families, and family structures. This week will feature a guest lecture by Dr. Madeleine Wong, Professor of Geography and African Studies. There may be one additional reading for this week, to be selected by Dr. Wong. Sassen, S. 1998. ‘America’s Immigration Problem’ in Globalization and its Discontents, 31-53. Parreňas, R.S. 2001. Servants of Globalization, selected pages. Espiritu, A.W. 2002. Filipino Navy stewards and Filipina Health Care Professionals: Immigration, Work, and Family Relations. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 11, 47-66. Assignment: Prepare 5 typed questions that demonstrate you have completed all of the readings for this week. These questions should draw out opinions and ideas of classmates, and relate to the academic content of the readings and the course. March 2nd Global Cities: Sites of Global Activity Global cities are centers of global economic activity, and often the most polarized cities in the world. In these cities, the movement of goods, services and people discussed in the past two lectures converge into radically polarized lifestyles. In global cities, the extremely rich and the extremely poor co-exist together and may occupy the same spaces. For example, illegal, temporary immigrants clean the office buildings of international lawyers in the middle of the night, and ‘indentured’ domestic workers care for the 6 Updated 2/8/2004 children of transnational corporate executives. In this class we will discuss the economic role of global cities, including the massive service economies filled by low-wage workers who are often immigrant women. Yeoh B, 1999, Global/globalizing cities, Progress in Human Geography, 23, pp. 607-616 Sasken, S. 2001. Global Cities and Survival Circuits. In Global Woman. Sassen, S. 2001. The Global City: New York, Tokyo, and London, 3-15 and 201250. Peck, J. and N. Theodor. 2001. Contingent Chicago: Restructuring the Spaces of Temporary Labor. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 25: 471-496. Assignment: Prepare 5 typed questions that demonstrate you have completed all of the readings for this week. These questions should draw out opinions and ideas of classmates, and relate to the academic content of the readings and the course. March 9th Work, Life, and Activism in Global Cities: Bread and Roses This movie provides a good example of several contemporary trends in global economics, including immigrant participation in work, the casualization and exploitation of part-time labor, specifically in janitorial services, and the changing nature of union organizing. Ethnicity, migration and gender are salient themes in this movie. Assignment: Book Review Due March 16th SPRING BREAK March 23rd Work and Life: Caring in a Global Context In this lecture, we will focus on non-waged and under-waged labor that is an essential part of globalized economies and global cities. I will highlight efforts by feminist economists to monetarily account for this work, and introduce historical and contemporary patterns in the conduct of non-waged work. This work includes, for example, care for children and relatives, domestic chores, and volunteer work. We will examine the gendered division of labor for these tasks, and how they tend to be differently valued than other types of paid work. In a growing industry of paid domestic work, inequalities such as race and ethnicity play an important role. Crittenden, A. 2002. The Price of Motherhood: Why the Most Important Job in the World is Still the Least Valued. New York: Henry Holt, 1-37. 7 Updated 2/8/2004 Ehrenreich, B and A.R. Hochschild, eds. 2003. Global Woman: Nannies, Maids and Sex Workers in the New Economy. New York: Metropolitan Books, 1-13. Cameron, J. and J. Gibson-Graham. 2003. Feminizing the Economy: Metaphors, Strategies, Politics. Parreňas, R. The Care Crisis in the Phillipines: Children and Transnational Families in the New Global Economy. In Global Woman, 39-54. Recommended Brush, L. 1997. ‘Gender, Work, Who Cares?’ Production, Reproduction, Deindustrialization and Business as Usual. In Revisioning Gender March 30th ‘Managing’ Motherhood in Global Economies: Josephine Movie Building upon the previous lectures, in this class we will look at paid domestic service, a growing part of the current global economy. This industry is largely dominated by lowincome, minority women, many who are immigrants, and emphasizes the devaluation of ‘domestic’ and feminine work discussed in last week’s lecture. This movie portrays the work of one global nanny working in Athens Greece, including her tensions in mothering her own family left behind in Sri Lanka. Pratt, G in collaboration with the Philippine Women Centre. 1999. Is this Canada? Domestic Workers’ Experiences in Vancouver, B.C. In Gender, Migration, and Domestic Service, ed. J.H. Momsen. London: Routledge, 23-39 Hondagneu-Sotelo, P. 2001. Cleaning up a Dirty Business. In Domestica: Immigrant Workers Cleaning and Caring in the Shadows of Affluence, 210-243. Karides, M. 2002. ‘Linking local Efforts with Global Struggle: Trinidad’s National Union of Domestic Employees’ In Women’s Activism and Globalization, 156-171. April 6th Transnational Corporations Transnational corporations are often seen as the drivers of economic globalization. In this class we will discuss the roles, operations, and networks of transnational corporations as analyzed by economic geographers. We will also analyze transnational corporations from a feminist lens, considering the gendered power structures built into corporations, the use of gendered divisions of labor, opportunities available for women, and feminist resistance to abuses of transnational corporations. Dicken, P. 1997. Transnational Corporations. In Global Shift, 177-199. Jackson, K.T., 1997, Globalizing corporate ethics programs: perils and prospects, Journal of Business Ethics, 16, 1227-1235. 8 Updated 2/8/2004 April 13th Feminized Global Economies: The Garment Industry In this class we will explore the growth in global economies that are reliant upon women and gendered divisions of labor. Focusing on the garment industry, we will discuss tactics of global corporations, patterns of labor and underlying gender relations, working conditions, and consequences for women participating in these economies. Collins, J. 2003. Threads (selected pages). Dicken, P. 1997. ‘Fabric-ating Fashion’: The Textiles and Clothing Industries. In Global Shift, 283-315. Louie, M.C.Y. 2001. Sweatshop Warriors (Selected case studies) April 20th ‘Feminized’ Global Economies: Selling Sex & Trading Bodies In this class we will analyze the global sex industry, which generated over $10 billion in income in Thailand alone in 1997. This industry, which involves pornography, prostitution, sex tourism, and mail-order brides, has a tremendous impact upon women, girls, and young boys. We will discuss various sex economies, the role of the governments in sanctioning sex industries, and a growing activist movement to challenge abuses associated with sex economies. Kempadoo, K. and J. Doezema. Global Sex Workers: Rights, Resistance, and Redefinition (Selected case studies) Landesman, P. 2004. ‘Sex Slaves on Main Street’ New York Times 24 January 2004 Bales, K. 2001. Because she Looks Like a Child. In Global Woman, 207-229. Brennan, D. 2002. Selling Sex for Visas: Sex Tourism as a Stepping-stone to International Migration. In Global Woman. April 27th Homework in A Global Context In this class we will examine paid work in the household, an activity that does not always appear in general accounts of globalization. Paying workers to labor at home is a strategy increasingly adopted by global and national companies, and entrepreneurs often work in their own homes. Sometimes this is a strategy chosen by women or men to help them balance family and work duties. While such paid work ranges from weaving carpets to white collar telecommuting, much of the homework is low wage and undertaken by women. In the lecture and through the case studies, we will discuss multiple types of homework and their geographic variation. We will also consider the opportunities that working at home entails for economic independence and/or more egalitarian gender relationships in the home. 9 Updated 2/8/2004 10 Boris, E. and E. Prugl. 1996. Homeworkers in Global Perspective: Invisible no More, pages 1-52 and 259-271. (Also selected cases) Phizacklea, A. and C. Wolkowitz. 1995. Homeworking Women: Gender, Racism, and Class at Work, 1-17, 100-122. May 4th Transnational Activism Globalization has helped facilitate opportunities for activists to collaborate and impact policies beyond their city or nation-state. Labor activists, environmentalists, and feminists have been particularly adept at building transnational coalitions and lobbying or challenging transnational institutions such as the World Trade Organization. In this class we will discuss the opportunities, challenges, and accomplishments of transnational activists, using a variety of case studies from around the world. Rosas, A.M. and S. Wilson. 2002. The Women’s Movement in the Era of Globalization: Does it Face Extinction? Louie, M.C.Y. 2001. Sweatshop Warriors, 19-58. Naples, N. and M. Desai, eds. 2001. Women’s Activism and Globalization (Selected cases) May 11th Final Paper Due, 5:00 p.m.