Lecture: The Great Depression

advertisement

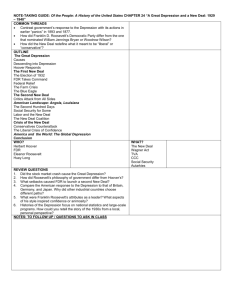

The Great Depression Americans in 1929 wanted to believe they were on what one analyst described as an, “. . . unlimited escalator of progress.” President Hoover announced at his inauguration that, “. . . the day [is near] when poverty will be banished from this nation.” Shortly thereafter the Stock Market Crash set in motion events that, combined with worldwide economic decline, created the Great Depression. America’s response to this crisis can be looked at in at least two ways through two potential thesis statements for this article. Try, “Drunk with nostalgia for the American Dream, the federal government took on the impossible task of making it come true for everyone.” Or, “Faced with unprecedented economic collapse and a resurgence of totalitarianism in Europe, the federal government rose to the occasion with innovative legislation and a commitment to defend freedom on a global scale.” I wrote both of those sentences and can never decide which is true. Maybe they both are—what do you think? Margin buying had contributed to the notion that our prosperity would never end. You could buy stocks with as little as 10% down in the 1920s. Inflated stock prices were going up so fast that after a short time you could make enough to pay back the 90% you borrowed from your broker with interest while still making a tidy profit. Then you went home and put the proceeds in savings, no? No. Most people could not resist borrowing more money to purchase even more stock at 10% down. Stock prices were wildly inflated as a result. Furthermore, large stockholders “pumped and dumped” stocks by purchasing large amounts of stock in companies like RCA and then paying journalists to pump up the reputation of the company. Three or four wealthy people would sell the stock among themselves to create the impression that there was a boom on a hot stock. When regular people (the suckers) began to buy the stock in earnest, the pool men would let the stock go a little higher, then sell all they had reaping huge profits on what quickly became nearly worthless stock. Both severe margin buying and “pump and dump” schemes are illegal now because they dramatically removed the Stock Market from the actual value of the American economy, hence the crash. The separation from actual national economic growth was understandable, however, with stories like that of a millionaire who turned his one million into thirty million in just eight months buying and selling stocks. Even a peddler was reported to have invested $4,000 at the same time and came out with $250,000. In 1927 there was a 40% rise in stock prices (not values). In 1928, prices went up another 35%. By September of 1929, stock prices were 400% above their level only five years earlier when Coolidge was president. In some inexplicable way, however, people began to collectively fear a collapse and began to “Sell! Sell! Sell!” on October 23rd, 1929. Few buyers came forward. Sensing a crash was imminent, Charles Mitchell saved the Market by organizing massive stock purchases by his bank and those of his associates. They staved off disaster for six days, largely because two of those days were on a weekend. On October 29th, however, another sell-off began which neither Mitchell nor anyone else could stop. By June of 1932, stock prices were at a level 50% below prices in Coolidge’s day. The Stock Market had crashed. The collapse of the inflated Stock Market is only the second domino that led to the Great Depression. Falling farm prices after World War I was the first, and by the end of 1929, the third was the fact that consumption dropped in a society with a consumer- based economy. Suddenly, “needs” went back to being luxuries or dreams. The US economy averaged a 50% slowdown in all indicators. As many as one third of the population was unemployed by 1933! Many fortunes were lost; those on the edge had nothing. Some remained prosperous like Joseph P. Kennedy, father of future President JFK, who had amazingly sold everything he had in the Stock Market just before the crash. He waited until prices bottomed out, and then put all his cash back in the market, ultimately reaping huge profits. Even the fortunate few who pulled that trick off had companies go bankrupt because of a lack of business, and laying workers off deepened the depression. Food lines formed! In America! President Hoover assured the nation that, “Prosperity is just around the corner.” He originally shunned involving the federal government in relief efforts saying, “If the government supports the people, then who will support the government?” Then Hoover gave in to pressure to begin relief programs including the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, an attempt to bolster the banking industry. While Hoover equivocated, the Bonus Army marched on Washington. These protestors were a group of veterans from World War I who had been promised bonuses (cash payments) upon retirement for their service in the war. They came with their families and camped around the lawns of the nation’s capital in July of 1932 and tried to directly lobby Congress to give them their bonuses early. In fear of a rebellion, Hoover sent Douglas MacArthur in with the Army to disperse the crowds. A baby died from exposure to tear gas, and it was hard for Hoover to make that sound like a good sacrifice to restore law and order. By the Election of 1932, it was also hard to make the fact that 20% of the banks in the US had closed sound like prosperity just around the corner. Hoover won the electoral votes of only six states. Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt, therefore, won in a landslide. Among other qualities, he possessed a dynamic grin which he flashed from behind a cigarette holder perched at a cocky angle above a raised chin. Such simple gestures spread hope to Americans desperate for any happy news. Stricken with polio as an adult, FDR had lost the use of his legs; however, he supported himself by his arms at his acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention. Such symbolic gestures of resolve continued. In his Inaugural Address he promised a New Deal to follow the Square Deal of TR, his cousin. After his speech he refused to attend the Inaugural Ball and went straight upstairs to his new office in the White House and got to work. Another cousin (fifth, once removed), Eleanor, was his wife and chief aide. Speaking of family, FDR was related to a total of eleven other presidents: George Washington, John Adams, James Madison, John Quincy Adams, Martin Van Buren, William Henry Harrison, Zachary Taylor, Ulysses S. Grant, Benjamin Harrison, Theodore Roosevelt, and William Howard Taft. But there is not really an aristocracy in America. FDR had followed the same path to power of his Oyster Bay Roosevelt cousin TR. He had been the Assistant Secretary of the Navy and Governor of New York. He was a Hyde Park Roosevelt and married TR’s brother Eliot’s daughter, Eleanor, who became his legs for him. She went so far as to tour factories and coal mines, exploits that she discussed in her “A Day in My Life” daily newspaper column. The Roosevelts were the first husband/wife presidential team, and some say the position has been a two-person job ever since. Eleanor sat beside her husband while he delivered “fireside chats” in his warm radio voice, or at least a machine made knitting-needle sounds to give that impression. In these speeches, the first delivered over the radio to the American people by their president, FDR used simple analogies to explain his policies. He never allowed himself to be photographed while sitting in his wheelchair. In fact, only one photograph exists in which he was shown incapacitated in the wheelchair, and it was taken while he was distracted by a child. What America did see was his grin with his chin up, and what they heard was the pleasing tones of a voice that was relaxed and confident. He said, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” Whatever that means, it sounded good and boosted morale. Privately, he said, “It’s time for the nation to be radicalized, at least for a while.” Therein lay FDR’s great plan. He attempted a revival of Progressivism and succeeded wildly. He used the Wisconsin Idea to collect a web of Cabinet personnel that lasted, incredibly, through all four terms he won as president. His Cabinet included the first woman to hold such rank in American history, Frances Perkins, a worker from Hull House who became the Secretary of Labor. His advisers, both official and unofficial, were known as his “Brains Trust,” and FDR made it clear to them that they were free to brainstorm and try just about anything to turn the Depression around. When he coined the phrase, “New Deal,” he had no idea what he intended to do, but through trial and error a response to the crisis was organized roughly along three headings, “Relief, Recovery, and Reform,” so yes, there were three R’s to go along with the three C’s (and the three T’s). Relief was intended to provide basic necessities to people without food, clothing, or shelter. Recovery measures attempted to restore the economy, and Reform measures were designed to prevent a depression of this magnitude in the future. The Roosevelt Administration worked with Congress to pass dozens of new laws to address the Depression, a feat still remembered as the First Hundred Days. Every president since FDR has tried to do something significant in that time frame, but not all succeeded. Banking seemed to be the place to start the New Deal. Even banks in New York City and Chicago were closing in the bitter winter of 1932-33. Upon entering office, FDR declared a “bank holiday” that closed all American banks for two weeks to prevent further “runs” on banks with no cash to give their depositors. A common attribute of people who suffered the loss of their life savings was to never trust banks again the rest of their lives. If you wondered why your great-grandmother kept her cash in a Mason jar stuffed under her mattress, this was why. FDR continued and expanded Hoover’s Reconstruction Finance Corp. (RFC) which loaned over one billion dollars to restart the banking system. When the bank holiday was over, 90% of US banks reopened. Maybe that’s what FDR meant by, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” His good morale was supposed to help the morale of Americans to have faith in the system, and then the system would work. Blows kept coming to America, though, literally. By 1934 the New Deal was floundering due to the Dust Bowl, a drought coupled with massive windstorms that stripped much of the Midwest and West of its topsoil. The classic American novel The Grapes of Wrath portrays the results of the Dust Bowl and was written by John Steinbeck while he was on relief (receiving special payments from the government for artists to relate the Great Depression in their works). Several critics of FDR’s policies emerged. Many of the most famous believed that FDR had not gone far enough! Governor Huey P. Long of Louisiana used the slogan, “Every Man a King!” to rally people to support the confiscation of the wealth of the rich for redistribution to the poor. He wanted to give homesteads worth $5,000 to people and pay a “salary” of $2,500 per year to all poor folks. His popularity was only checked by his being assassinated. Father Charles Coughlin’s radio show was so popular it is said you could walk all the way through town on a summer night and hear the whole show as it filtered out of one screened window after another. Coughlin was, of course, a Catholic priest who blamed the Depression on Wall Street and called for the nationalization of all banks, a frightening prospect indeed. He could not quite contain his anti-Semitism, however, and was never a serious political contender. Dr. Francis E. Townsend proposed that the federal government give $200 per month to unemployed people as long as they agreed to spend it all that month, an attempt at forcing Americans to be consumers again. Remember, radicals like these allowed FDR to try ever more radical measures without being checked. Still Roosevelt became so controversial in his use of presidential power that Americans either loved or hated him. Poor people embraced his message that they had constitutional rights, too. The wealthy referred to him as, “That man in the White House” and said he was a traitor to his class. They said he was going to produce chaos by robbing the wealthy to give to the lower classes. The American Liberty League was formed and spent millions to discredit both FDR and the New Deal. They realized something was gone in America, and you should know what it was—laissez faire. The Roosevelt Administration shamed all pretenders who sought to match his record in the first hundred days of a presidency. FDR was, however, the only one to ever accomplish such sweeping change in such a short time because he was the first to indulge in deficit spending on purpose. Convinced by Alfred Maynard Keynes that the government had a duty to “prime the pump,” Roosevelt initiated huge spending programs to flesh out his three R’s and quickly spent more money than even a raised income tax could bring in. From then on he borrowed the money to spend and created huge deficits. America has relied on deficit spending to one degree or another ever since. Our next installment will be dedicated to seeing if he spent the money wisely.