Are contemporary societies becoming more secular?

advertisement

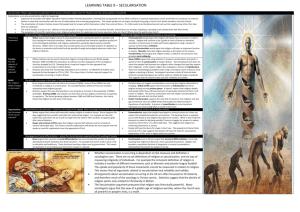

AKC 2 General – Spring Term 2007 – Religion in the contemporary world: social scientific perspectives 22/01/07 AKC 2 – 22 JANUARY 2007 ARE CONTEMPORARY SOCIETIES BECOMING MORE SECULAR? DR MARAT SHTERIN, DEPARTMENT OF THEOLOGY AND RELIGIOUS STUDIES The question of whether religion, religious thinking and institutions are diminishing in significance in contemporary society is among the most hotly debated issues within the contemporary sociology of religion and in society in general. It is known as the secularisation debate. I. Secularisation theory I.1. What is secularisation and secularisation theory? The term secularisation can have a variety of meanings: state policy of expropriating church property state policy of forcibly exluding religion from public life (such as in former communist countries – the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Albania, or, in a softer form, in Turkey). These policies are usually informed by the ideological position that society benefits from being less religious and being less influenced by religious institutions. In this sense, a more appropriate word is secularism For our purproses we refer to secularisation in a neutral way, denoting “a social process whereby religious institutions, thinking, and consciousness are losing their social signifance” (Bryan Wilson) Secularisation theory seeks to establish a causal relationship between modernisation of society and the role of religion in it; arguing that modernisation of society (associated with industrialisation, urbanisation, and mass political participation) leads to diminishing role and authority of religion. This theory has its proponents and opponents. I.2. What are the indicators of and evidence for secularisation? Proponents of the secularisation theory point to some observable trends indicating that secularisation is actually taking place (see also tables attached): Previously accepted religious symbols, doctrines, and institutions lose their prestige and importance We live in greater conformity with the material world and no longer have much interest in the supernatural Religion has become a private matter and no longer has much influence on other spheres of life We are increasingly less committed to religious values and practices Religion has become a ‘leisure pursuit’ rather than a significant public endeavor I.3. Why is secularisation taking place? According to the proponents of the secularisation theory (e.g. Bryan Wilson, Steve Bruce), religion loses its social significance as a direct and inevitable result of three processes involved in modernisation: rationalisation: a process whereby society is increasingly organised according to rational, ‘means-toends’, principles and procedures, in which religious concepts and values simply have no place differentiation (social fragmentation): we live in societies with increasingly specialized institutions (the economy, education, health, politics, family, etc). Religion is no longer directly relevant to the operation of any of them and social system as a whole decline of community (societalisation): modern life is increasingly organised and regulated not within close-knit local communities, but on the societal level governed by state bureaucracies. Religion used to be at the heart of local community life, and it is irrelevant for society regulated by bureaucratic rules II. Criticisms of the secularisation theory. II.1. Opponents usually cite the following evidence against secularisation Even though ‘orthodox’ religious beliefs have lost their appeal, the available evidence indicates that most people still hold religious beliefs Religion remains highly socially significant in lives of many social groups, most notably many ethnic minority and migrant groups (e.g. Muslims) Some religious movements have experienced considerable resurgence, in particular fundamentalist, Pentecostal groups, and New Religious Movements In many parts of the world religion is still prominent, e.g. in many sections of the Muslim world, Latin America, Africa, and some post-communist countries If modernisation inevitably leads to secularisation, then why is religion such a big thing in the most modernised country in the world, i.e. the U.S.A? II.2. Some alternative theories and explanations. Rational Choice Theory (Rodney Stark, Roger Finke) of religious participation is based on the philosophical premise that religion is inherent in the human condition and therefore will never disappear from the social domain. The level of religious participation, however, can fluctuate depending on the degree to which a particular ‘religious economy’ is regulated by the state: the more the state regulates religion and supports a dominant religion (religious monopoly) in a particular country, the lower the level of religious participation is likely to be in that country. Religious de-institutionalisation (Danièle Hervieu-Léger, Grace Davie) argues that religion is changing its forms and manifestations, but not disappearing; it is only institutional religion that is losing its social significance, while numerous new forms of religion (‘patchwork’, ‘bricolage’) are constantly put together by individuals and groups both within and outside institutional churches. European exceptionalism (Grace Davie, Peter Berger) refers to the view that rather than being an example par excellence of inevitability of secularisation, Europe is an atypical case of marginalized religion, owing perhaps to its peculiar history and church-state relations. Further Reading Berger, Peter (2000), The Sacred Canopy: Elements of the Sociological Theory of Religion, MA: Blackwell Bruce, Steve (ed., 1992), Religion and Modernisation, Oxford: Oxford University Press Bruce, Steve (2002), God is Dead: Secularisation in the West, Oxford: Blackwell Casanova, Jose (1994), Public Religions in the Modern World, Chicago: Chicago University Press. Davie, Grace (2000), Religion in Modern Britain: A Memory Mutates, Oxford: Oxford University Press Stark, Rodney and William Sims Bainbridge (1985), The Future of Religion: Secularization, Revival and Cult Formation, Berkeley: University of California Press. Stark, Rodney and Finke Roger (2000), Acts of Faith: Explaining the Human Side of Religion, Berkeley, CA, University of California Press Wilson, Bryan,(1985), “Secularisation: the Inherited Model”, in Hammond, Philip (ed.), The Sacred in the Secular Age, Berkeley, Ca: University of California Press, pp. 9-20 Wilson, Bryan (1992), “Reflections on a Many Sided Controversy”, in Bruce, Steve (ed), Religion and Modernisation, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 195-210. Table 1: Church membership in the United Kingdom 1975 1980 1985 1990 2000 Anglican Baptist R. Catholic 2,298,000 236,000 2,519,000 2,180,000 240,000 2,238,000 2,016,500 243,500 2,204,000 1870,500 232,000 2,168,000 1,450,000 230,500 1,890,000 Independent Methodist Orthodox 252,000 596,500 197,000 253,000 540,000 203,000 308,500 500,500 223,500 342,500 475,500 266,000 335,000 373,000 288,000 Presbyterian Pentecostal 1,641,500 104,500 1,505,000 127,000 1,385,000 138,500 1,288,500 158,500 1,060,000 186,000 Source: Peter Brierley, The Tide Is Running Out, 2000 Table 2. Church membership in West Germany, 1950 - 1990 year 1950 1970 attendance (RC + Lutherans); 84 56 % of population Source: Jeff Haynes, Religion in Global Politics, 1998 1990 46 Full details about the AKC course, including copies of the handouts, can be found on the AKC website at: http://www.kcl.ac.uk/akc. Please join in the Discussion Board and leave your comments. If you have any queries please contact the AKC Course Administrator on ext 2333 or via email at dean@kcl.ac.uk. You must register for the course, using the form on the website, before registering for the exam. Please note the AKC Exam is on Friday 23 March 2007 between 14.30 and 16.30. EXAM REGISTRATION opens on Friday 26 January 2007. Please reply to the email you will receive giving your full name and student ID number.