Immunity to Change in Progressive Faith

advertisement

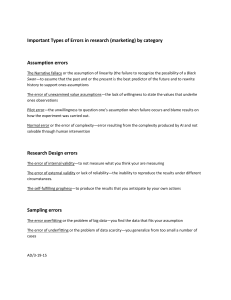

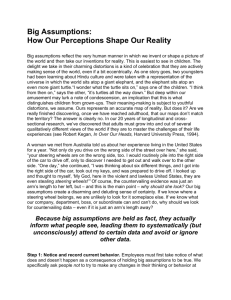

Immunity to Change in Progressive Faith Communities By Rev. Tom Thresher, Ph.D. In their 2009 masterpiece, Immunity to Change: How to Overcome it and Unlock the Potential in Yourself and Your Organization, Robert Kegan and Lisa Lahey bring a decade of experience to a powerful process laid out in How the Way We Talk Can Change the Way We Work. We are adapting this process to church settings entitling it Transformational Inquiry. In this paper I will suggest some essential differences between how Kegan and Lahey have used the Immunity to Change process in business, educational, and government settings and the requirements for adaptation to progressive faith communities. Brief Overview of Immunity to Change Immunity to Change takes four powerful steps (using a four column worksheet) into an individual or a group’s invisible immunity to change. It does this by revealing the protective commitments and assumptions that are generally hidden from our awareness. The process begins with a visible commitment, one that is generally quite noble and includes behavioral aspirations. The second step is to identify what the individual (or group) is doing or not doing to prevent that commitment from being realized in the world. In other words, what are the behaviors that prevent the noble aspirations from happening? If, for example, my goal is to delegate better (1st column: noble commitment), I may discover that I thwart this goal by micromanaging (2nd column: doing/not doing). This is fairly standard fare for self-improvement work. The genius of the process begins with the next step. Rather than resolving to change the behaviors that undermine our noble aspirations, Kegan and Lahey invite us to consider the nature of competing commitments that may drive our counterproductive behavior. This 3rd step asks us first to consider the imagined consequences of doing things differently; i.e., what if I didn’t micromanage? What kind of fear or anxiety arises for me? I may notice that I'm anxious about shoddy work being done under my authority. So, my competing commitment may be that I'm committed to not looking bad to my superiors. (I may also be committed to delivering quality work— a noble commitment — here, however, we are interested in the fear or anxiety that underlies the behaviors that thwart our first column commitment). The fourth step (4th column) flips things once more by making an “if…then” statement: “I assume that if …….then…..” In this example, “I assume that if I look bad to my superiors, then they will think less of me.” We did deeper by asking, “If you look bad to your superiors, what do you believe will happen? In our example, the answer might be, “I assume that, if I don’t always look good to my superiors, they will fire me.” And what will happen then? “If they fire me my life will crumble, my family will deteriorate, and I’ll be alone and destitute.” By its nature the Big Assumption describes a catastrophe. The rational mind looks at this sequence of deepening assumptions and says “that’s ridiculous, get over it.” But we have unearthed something very important here: a series of assumptions that may be grounded in childhood experiences and are unexamined. As Kegan and Lahey articulate so beautifully, these are not assumptions we have, they are invisible, powerful assumptions that have us. Now we have something to work with. We have a glimpse into the invisible meaning-making structure of our lives. Most people want to immediately ignore their Big Assumptions and move on. But that is just the mind doing its job of protecting us by reburying painful revelations. The goal is to make small, incremental adjustments to our foundational assumptions that impact the entire superstructure of our identity. In Kegan and Lahey’s process, the incremental work of shifting Big Assumptions happens through iterative tests that are safe, manageable, and practical in the short term. These “safe tests” challenge the veracity of the Big Assumptions. The tests may neutralize the Assumptions or, more often, shape them into a more nuanced and mature form. This barebones description of a transformative process will, I hope, suffice for distinguishing our work in churches from that of the typical venues encountered by Kegan and Lahey. Our reasons for adapting their process are important. First, my church has nearly a ten year record of success using the Immunity to Change process. We have watched a variety of individuals make important, substantive changes in their lives. It has also helped strengthen our culture of trust, mutual support and personal adventure. We want to share this. Second, we consider Transformational Inquiry (the Immunity to Change process) to be a spiritual practice, a modern day equivalent of the ancient art of Inquiry. We say more about this in the final section. The Church Context The church provides a substantially different context than the business, government and educational settings where Immunity to Change has been so successfully applied by Kegan and Lahey. Their research emphasizes how essential a really strong first column commitment is to the success of the change process. In business, government and education settings there is typically have a group of individuals working together 40+ hours per week on a common goal. Individuals have significant personal investment in the success of the institution and in doing their job well, if for no more noble reason than retaining employment. This personal engagement is ideal for motivating change. The church is quite different. It is (primarily) a volunteer organization with diffuse (often abstract) goals and intermittent involvement — the opposite of the grounded motivation in other institutions. This makes it difficult to find the kind of powerful, noble commitment so essential in Kegan and Lahey’s work. This difficulty rebounds on the safe testing of Big Assumptions. We find that in the church setting, folks are generally deeply motivated to unearth their Big Assumptions, their motivation evaporates when it comes to iterative safe tests. This dramatically different context leads us to some very different strategies, with a good deal of success (and on-going experimentation). First, we return to a technique presented in How the Way We Talk Can Change the Way We Work. We begin with complaints. Almost everyone likes to complain. (We invite those who find it difficult to complain to check what internal processes block them from seeing their personal judgments and corresponding complaints). Complaints create an instant aura of playfulness and vulnerability that supports the entire process. From a spiritual orientation, it also encourages an important shift in self perception and humility. We have used different approaches to Transformational Inquiry (Inquiry for short). We may go through the four columns in one evening and focus our attention on safe tests and other means of challenging the Big Assumption. Other times we take advantage of the time frame offered by the church setting and spread the four column process out over four weeks, spending a week elucidating each column. (This also shifts the process in the direction of spiritual practice). For example, we may form pairs of participants for part of our first session to elicit complaints and elaborate on them in the group as a whole. We then point out that we wouldn’t complain if we didn’t stand for something important. Underlying every complaint is a noble commitment. So the first week’s homework is simply to notice judgments and complaints whenever possible and briefly investigate the noble commitment that motivates it. We often use a simple guided meditation at the end of the session to reinforce our work together. By simply inviting folks to close their eyes, breathe and feel what it’s like to experience the noble commitments beneath their complaints helps folks connect during the week. The second meeting explores what we are doing or not doing that thwarts our noble commitment. The homework is to observe the actions we take or don’t take that undermine our noble commitment. The tricky part is to not fix it, in any way. Rather, the practice is to observe and acknowledge the various actions and inactions that counter our desired behavior. If folks actually practice during the week (its hard work), they return both annoyed and attentive. We dive into competing commitments the third week. Greater bonding in the group is grounded in the laughter of mutual recognition. Insights may be deepened using imagery and inviting folks to take on the physical poses of the noble and competing assumptions. During the week they are invited to have internal conversations between the noble commitment and the competing commitments. Again, this is not about denying or fixing the competing commitments, but about observing our individual immunities to change in action. By this point folks are beginning to understand what it means to stay in the tension of unresolved issues long enough to be changed by them. Our fourth week moves into Big Assumptions. We often invite a few individuals to follow their Big Assumptions to a depth that becomes inarticulate, just a feeling. It is a powerful recognition of how foundational these assumptions are. This recognition is sometimes reinforced with bodily movement (taking the physical pose of the Big Assumption) and imagery (getting a feel or image of the Big Assumption). During the week folks are asked to notice their Big Assumption in action, and also to record counter examples; that is, when their Big Assumption was not correct. We also ask folks to begin writing a history of the Big Assumption in terms of events that helped establish — or “proved” — the Big Assumption to be true. These will be used later. Working with Big Assumptions As mentioned, church folks don’t work with each other every day and don’t have the deeply grounded motivations provided by business, government and educational institutions. We find we need a menu of tools to engage folks in the on-going process of questioning their Big Assumptions. Tweaking the Big Assumption requires some way of challenging the Big Assumption, raising doubts about its validity, then absorbing that doubt. It may also involve creating a more nuanced articulation of the Big Assumption. Here is our menu (so far): Safe Tests The strategy of Safe Tests follows Kegan and Lahey’s recommendations with some modifications. A safe test is just what it suggests, an action that challenges the veracity of a Big Assumption, and is modest, doable and can cause minimal or no damage. As indicated, in the church we often get strong push back or lack of action when we ask individuals to create rigorous safe tests of their Big Assumptions. A less demanding, though still very effective, approach is to observe the ongoing tests that life presents on a daily basis. If, for example, my Big Assumption is “I’m not good enough,” I am likely confronted with evidence throughout the day that either confirms or counters that Big Assumption. Since I am already looking through this Big Assumption, I quite naturally take in the evidence that confirms the Big Assumption and filter out evidence that disaffirms it. It takes conscious attention to notice evidence that counters our Big Assumption, and it tends to slip from our memory very quickly. Writing down counter-evidence is essential. Bringing this information to the group is vital. The affirmation of the group reinforces the plausibility of the counter-evidence; others in the group will often cite additional evidence that counters the Big Assumption. In this example, my community will readily recognize instances when I have truly been good enough and can remind me of these events. Additionally, group pressure can keep me from denying or discounting this contrary evidence. The Work of Byron Katie Given the lack of daily interaction among a church community, personal practices to turn to throughout the day is essential for change. The Work of Byron Katie provides a deceptively simple practice with the power to challenge Big Assumptions. Using the history of the Big Assumption constructed in terms of evidence for a Big Assumption we ask four questions: 1. Is it true? 2. Can you be absolutely certain it is true? 3. How do you react? How do you feel when you believe that assumption? 4. Who would you be without that Big Assumption? Then turn it around. To return to our example of the Big Assumption “I am not good enough.” One piece of evidence from childhood might be that, when I went to play football, I chickened out when I saw the other kids playing. My father was very disappointed. As a child, I concluded that “I'm not good enough.” String a few of these together and it is quite easy for a youngster to form the assumption that “My father doesn’t love me because I'm not good enough.” (Rationality and consistency are unimportant in Big Assumptions). Then run through the four questions: 1. It is true that “My father doesn’t love me because I'm not good enough?” Look inside yourself and answer honestly. The answer may be a resounding “Yes!” 2. Can I be absolutely certain that “My father doesn’t love me because I'm not good enough?” Well, perhaps he withdrew his love for a moment, but quickly loved me again. Perhaps I misperceived his look: He didn’t actually say anything. Perhaps. Perhaps. Often, after a bit of reflection, our certainty wavers and we may answer “no.” If the answer “yes,” persists, proceed. 3. How do you react when you believe “My father doesn’t love me because I'm not good enough?” Allow yourself to settle inward and experience how that feels. 4. Who would you be without the thought “My father doesn’t love me because I'm not good enough?” Again, turn inward and do your best to imagine not having that thought. Allow yourself to experience that. Now turn it around. A turn-around means to look at some opposite versions of the thought then, give some examples to support the turn around. One turn around: “My father does love me even though I didn’t play football.” Evidence: We continued to do cool stuff together; he never said he didn’t love me; shortly afterward he didn’t seem upset. A second turn around: “My father thinks I'm good enough to play football.” Evidence: he took me to try out in the first place; he commends my ability; he continues to practice with me. Our use of Katie’s four questions does not challenge the Big Assumption directly. Rather, it challenges the validity of the evidence supporting it. By bringing the four questions to the various pieces of evidence outlined in the history of the Big Assumption the Big Assumption is weakened. Our focus in a faith setting is to loosen the grip of the Big Assumption, hold it in the light of awareness and notice as it begins to change of its own accord. The Work can be practiced very effectively in pairs in the group setting. It requires no expertise to invite your partner to answer each of the questions and try some turnarounds. With very little practice folks are able help one another experience profound insights and release. Role Playing Role playing is another tool we use in the ongoing effort to keep folks engaged in challenging their Big Assumptions. This takes a variety of forms. We have conversations between the noble and competing commitments or between the noble commitment and a Big Assumption. Or we can role-play our evidence for the Big Assumption. In our example, this might take the form of someone playing my father and telling me that he was disappointed about my not playing football, but that not once did he stop loving me. Transformational Inquiry and Spirituality In the conclusion to Immunity to Change, Kegan and Lahey make a remarkable statement: [O]ur deepest human hunger [is] to experience the continuing unfolding of our capacities to see more deeply (inwardly and outwardly) and to act more effectively and with greater range. From the Christian perspective, this is a profound statement of incarnational spirituality. Christianity is often oriented to the next world, what will happen after we die. A more incarnationally grounded Christianity focuses on living life abundantly. (“I have come that they may have life, and that they may have it more abundantly”, John 10:10). Abundance does not mean more stuff, it means an “expanding capacity to see more deeply and act more effectively.” Collectively, in Christian terms, it means to bring forth the Kingdom of God. From an Eastern perspective, the classic statement of Inquiry comes from the great Indian sage Ramana Maharshi. He said “ask yourself ‘Who am I’ until you know.” In other words, investigate the “I” that claims to see, feel and think. “Who is having this thought?” “What knows that I am thinking this thought?” Ramana claimed that consistent Inquiry was the direct path to enlightenment. We Westerners are not particularly good at sitting still for hours in meditation or focusing our attention on such a question. We prefer action. I contend that Ramana’s process and Immunity to Change share a common purpose that goes to the heart of spiritual practice: Making that which is subject into object. That is, to take the perspective through which we see —our Big Assumption — and make it an object upon which we can reflect. Just as the question “Who am I?” makes the assumption of my separate existence into a question to be explored, Immunity to Change brings the unexamined architecture of my meaning-making and personal identity out for examination. And, just as the investigation of “Who am I?” leads to the realization of no-self, The Work of Byron Katie deconstructs the pillars of my identity (my Big Assumptions) and opens me to Mystery. An additional motivation for using Transformational Inquiry derives from the lack of spiritual practice among progressive Christian churches. Our natural constituents, the “spiritual but not religious” have deserted churches, in part, because we have no serious practice. We hope that, by introducing a contemporary spiritual practice in churches, they will become more relevant and simultaneously ground their social justice work in inner wisdom. Conclusion Churches bring three unique gifts to our contemporary society. First, the great mythic stories that contextualize our personal meaning-making stories emanate from Christianity. Because churches “own” these cultural stories they have the legitimacy and the obligation to adapt them to contemporary needs. Second, churches are allowed into peoples’ hearts and minds and invited to change them. Third, churches have a different time frame: enough time to allow individuals the time it takes to make personal changes. Because of these gifts, churches can (must?) lead the evolution of human consciousness essential in these increasingly complex times. The Immunity to Change process developed by Kegan and Lahey is an important tool, particularly for progressive churches. Progressive churches are poised to lead and sustain an unfolding of awareness and caring essential to the challenges we confront as a species. Transformational Inquiry gives churches a tool to deepen their spiritual practice while enriching their efforts for social justice.