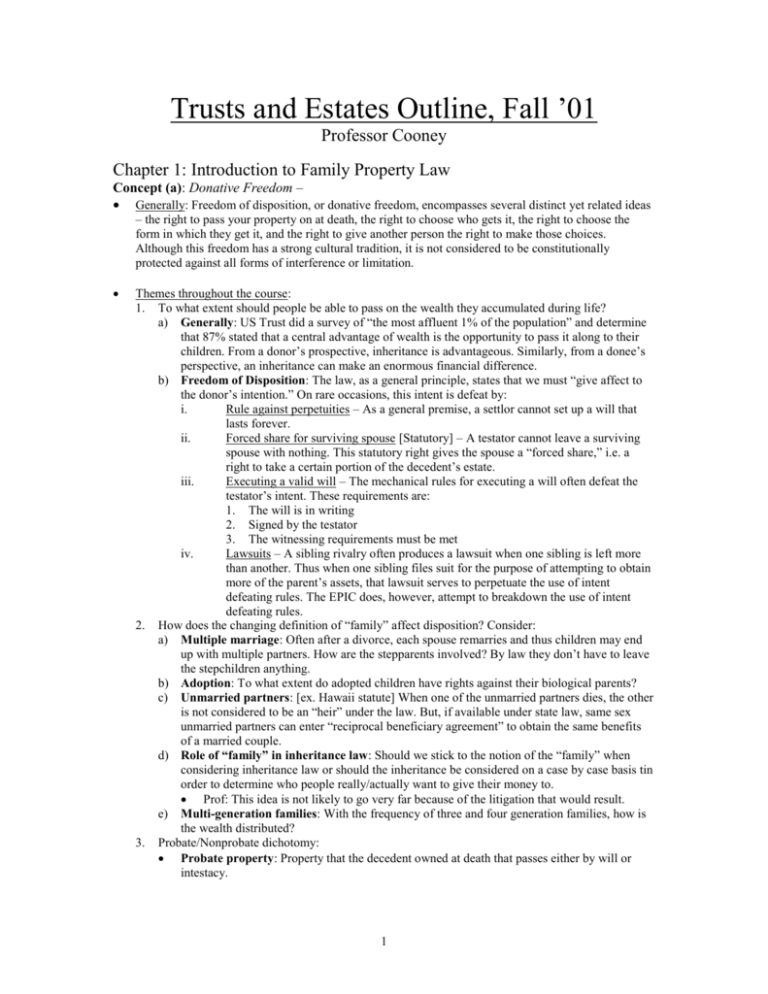

Trusts and Estates Outline, Fall `00

advertisement