Girl Power: Patriarchy in Sheep's Clothing Analysis

advertisement

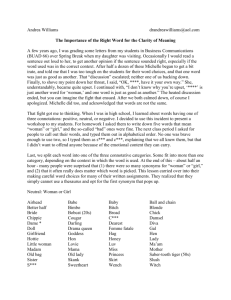

Girl Power: Patriarchy in Sheep’s Clothing Welcome to Harvard Law School Graduation: a pert, slender blonde wearing bright pink lipstick and a mortarboard is giving the graduation address; her classmates leap up to applaud her as the camera focuses on her darkly handsome boyfriend. Beautiful! Fabulous! What, you wonder, is this girl’s story? Her story lies in the plot of the 2001 movie Legally Blonde, a pink and fluffy spectacular starring Reese Witherspoon. Reese plays Elle Woods, who decides to follow her ex-boyfriend to Harvard Law after their breakup. A fashion design major, Elle hits the books pretty hard to get decent scores on her LSATS, even missing parties – and then hires a professional to film her in a soft-core porn admissions video, focusing on Elle floating in a cool blue pool wearing a tiny pink bikini. Lo and behold, it wows the white, middle-aged male admissions board, and Elle goes on to take campus by storm. And there’s good reason Elle makes such a splash: she turns out to be he only beautiful girl at Harvard. All the rest of the girls there spend their time studying and doing nothing else; they are dull, boring, and above all, unpretty. These smart women do anything but have fun. Most of them blur into one bespectacled, intellectual image, but there’s one young woman among them who is even worse than dull – our token Feminist. She has dreadlocks and a defensive attitude, talks about nothing but political rallies and is, of course, a lesbian. Elle hates her. Unrealistic? Sure, but what do we expect from the movies? The real problem begins when the ideas propagated by films that claim to be a “feel good, girl-power movie,” as People magazine called this particular brain-number, seep into our everyday existence. With the tagline “believing in yourself never goes out of style,” the kind of empty platitude that masquerades for self-esteem in America’s touchy-feely pop psychology landscape, Legally Blonde is just one in a chain of girl power movies, Tshirts, books, and philosophies falsely represented as empowering that have been stealthily creeping into our culture. While the producers of this film would have us believe that this movie’s message is that all blondes aren’t dumb (in an attempt to contradict one of Hollywood’s earlier stereotypes), and harp on how wonderful it is that a pretty girl could make it in law school, that’s not what really comes across. Sure, Elle was disappointed when she found out she got an internship on basis of her looks, but shouldn’t there be more then just disappointment? In order to avoid this objectification, perhaps girls shouldn’t send tantalizing, sexual videos to the admissions committee. What Legally Blonde really teaches its viewers is that most smart girls aren’t pretty; smartness is intolerable in a woman unless she is pretty; and that any politically aware or feminist women are radical lesbians on the lower strata of society. These negative images have definitely traveled farther than the silver screen – in a recent New York Times column, for example, Maureen Dowd presented a few interviews with female Harvard students who admitted they kept their college a secret from their male dates. “It’s the kiss of death,” one female student lamented. Apparently, young men are still threatened by women who are smarter than they are, or who might make more money. No, Legally Blonde is not an isolated cultural blunder, and we can buy into similar philosophies in any mall. Take a look at the shelves of Old Navy or Claire’s. Under the guise of raising girls’ self-esteem, these stores stock their shelves with shirts that say: Boys are great – every girl should own one; Boys Lie; I Love Boys; I Love Shopping; Perfect; 90% Angel; Princess; Porn Star; and Playboy. What do these T-shirts teach our girls? Manufacturers get away with these slogans by shoving them under the girl power umbrella, telling us they preach empowerment. If you open Delia’s, a mail order clothing and accessory catalogue sent to countless teen and preteen girls, models sort similar shirts at the top of a page that reads at the bottom, “Girls can rule the world,” “be anything you want,” or any number of other tired slogans. But if we look past the accompanying cheerful catchphrases to what the T-shirts really mean, we can find another story: they promote sexism (objectification of males), heterosexism (all hetero-themed opinions), egomania (narcissism instead of betterment), and the typical role of female as consumer (emphasis on shopping) and sex object (glorification of sex industry). The Playboy shirts alone show how young women have bought into the concept that this male-defined concept of beauty is true desirability. What is empowering about this? These slogans, inscribed on shirts, stickers, notebooks, and many other marketable objects, are widespread to say the least. But hasn’t anyone else noticed what they say? Unfortunately, there doesn’t seem to be a lot of feminist debate about them these days, most likely because popular culture has widely accepted girl power since the Spice Girls coined the term. Today’s “third wave” feminists who came of age in the 1980s, women such as Jennifer Baumgardner and Amy Richards, would have us believe the struggle for feminist ideals is no longer needed. In their 2000 book Manifesta: Young Women, Feminism and the Future, Baumgardner and Richards say, “For our generation, feminism is like fluoride,” meaning all modern girls are unconscious feminists. Or are they? I agree that certain concepts have found their way into our water supply, so to speak, but they are not truly feminist. Indeed, Baumgardner and Richards go on to disprove their own statements in Manifesta; Reason book reviewer Cathy Young points out that the authors’ “writing all too often confirms the very stereotypes of young feminists that they seek to disprove--namely, silliness and self-absorption.” The qualities Young mentions all appear in girl power clothes, movies, music, and magazines. I propose that although girl power supporters claim the trend is really about accepting and celebrating girls and all forms of sexuality, what it’s really doing is making over young women into exactly what men want. This isn’t new, either – the same thing happened in the 1960s with the advent of the Pill. The Pill left birth control completely up to women for a change, so men could have as many one-night stands as they wanted, no strings attached. So what if a woman could have them, too? What ended up happening was that women, in the name of equality, adopted the less responsible male behavior that had long been a societal double standard instead of bettering the behavior of both genders. So, we’re left with deciding what qualities are desirable. If we want equality, we should want equality on the best possible terms instead of just settling. Should feminists eager for a generation of “empowered” girls have to settle for girl power? Let’s say the definition of a third wave feminism is, as Baumgardner and Richards claim, wanting “[one] to be whoever [one is]--but with a political consciousness.” This definition implies a desire to step away from requiring an image to go along with an –ism, as well as for mindfulness in living. Yet, does girl power fulfill this definition? I don’t believe it does. Rather, girl power creates yet another narrow image girls and young women are expected to fit into. Not only is girl power just one more way of telling girls how to be girls, but the image it advocates is degrading. There is no political consciousness in a 12-year-old girl, or a 25-year-old, for that matter, who wears a shirt emblazoned with the Playboy bunny – the message she sends is that she is ready and willing to be used. Why should an independent young woman proclaim her value as an object? Feminism, a theory that backs choice balanced with political consciousness, should warn against this unconscious propagation of oppression. Feminism says you can; girl power says you have to. It even manages to be both homophobic and anti-male simultaneously. The same version of a young female model wearing a “Boys Lie” T-shirt would definitely turn up her nose at the mention of lesbianism except in the bi-curious, threesome male fantasy variety. Even the blatantly anti-male “boys lie” is juxtaposed with the fatuous “I Love Boys”. Boys may lie, but what the heck. It’s still ok to be their Porn Star. Feminists’ struggles against objectification are all invalidated with each mother who believes she is teaching her daughter the value of self-worth by renting Legally Blonde or buying her a “Princess” T-shirt. But what can we expect from our society? Is girl power the best we can get? Will it actually bring about a revolution of enlightened women on an equal level with men, as some desperate feminists hope? I doubt it. As Cathy Young reminds us, for an empowering dialogue about men and women in society to succeed, it must include both men and women. I would add that it also needs to harbor active consciousness – one needn’t speak only of politics, or attend all of the nation’s rallies, but should be aware of what his or her behavior and choices says. Dancing drunk in a dark club wearing revealing clothing does not say “I respect my body,” no matter what girl power advocates might want us to think. And, as we can see from the contradictory, anti-male and Hefner-supporting, overtly sexual philosophy behind girl power, neither of these stipulations is met. Men are both shut out of the dialogue and expected, even preferred, to be objectifiers. Feminism is about equality, human rights, and choices. It does not expect all feminists to eat whole grains and organic vegetables, or cut off their hair, but it does expect some kind of consciousness, some awareness of politics, gender, and a sense of self. On the contrary, girl power is about image, prettiness, and heterosexist sexual attractiveness. I think we shouldn’t have to settle for accepting girl power as the best version of feminism for this generation, but I’ll take a conscious and feminist stance – I’ll skip the aisle with Reese Witherspoon and Perfect shirts, but I’ll keep talking about them. To modify Legally Blonde’s catchphrase, we’ve got to be worth believing in before we can believe in ourselves.