Seizures in Dogs and Cats: What are the treatment options

advertisement

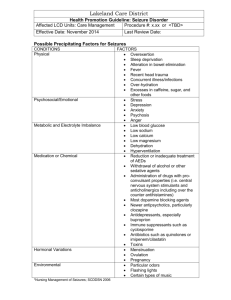

Seizures in Dogs and Cats: What are the treatment options? Which Anti-Epileptic Drug is best for this patient? Ashley Bensfield, DVM Small Animal Track 2012 ISVMA Annual Conference Proceedings Numerous drugs are available for use in veterinary medicine because the perfect antiseizure drug has not yet been found. Therefore, the Anti-epileptic Drugs (AEDs) available must be critically evaluated for each patient to best optimize treatment. The most common AEDs in veterinary medicine include: phenobarbital, bromide, levetiracetam, benzodiazepines, zonisamide, and anesthetics. Less commonly used AEDs include Rufinamide, phenytoin/Fosphenytoin, Topiramate, Felbamate, Pregabalin/Gabapentin, and Valproic Acid. Phenobarbital: Phenobarbital is one of the most commonly used AEDs in veterinary medicine. It is available in tablets as fractions of a grain or in traditional milligram sizes as well as a liquid formulation. Phenobarbital is inexpensive and readily available. Phenobarbital is most effective for treating grand mal seizures. Higher doses are required to treat cluster seizures and partial seizures. Phenobarbital is metabolized by the liver, and it is contraindicated in patients with liver disease. Concurrent CYP450-metabolized drugs should be avoided or used with caution to avoid toxic build up of phenobarbital levels. Because cumulative liver damage can occur, phenobarbital is relatively contraindicated as the sole maintenance drug for lifelong therapy in a young patient. The common side effects of phenobarbital include significant polyphagia, polyuria and polydypsia. Sedation regularly occurs and is expected to last for about 2 weeks during the initial phase of treatment. Occasionally, serious side effects can occur during the first few months of treatment including bone marrow dyscrasias or liver failure. Starting doses range from 2-2.5mg/kg BID to TID. The rule of thumb is that 6mg/pound/day will achieve a blood level of about 35. Cats may require less phenobarbital to reach an acceptable blood level when compared to dogs. Steady state blood levels are first achieved after about 2 weeks of therapy. However, shortly thereafter, hepatic enzyme induction begins, which often causes the blood levels to drop. For an average patient, the first phenobarbital blood level should be measured after 1 month of consistent dosing. There is no significant difference between peak and trough measurements for animals receiving between 2-10mg/kg/day. Peak and trough measurements can be used, however, to calculate serum half life to determine if three times daily dosing is needed. A discrepancy exists between reported laboratory therapeutic ranges and what clinically is acceptable. Laboratories may report a range from 15-45. However, studies have shown that seizure control is best achieved between 20-30, and a level of greater than 35 is strongly correlated with an increased risk for liver disease. To monitor systemic tolerance of the drug, a CBC and chemistry profile should be performed at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, and then every 6 months during phenobarbital therapy. Paired bile acids testing should ideally be performed prior to the start of phenobarbital therapy and then at least yearly thereafter. Phenobarbital is relatively well tolerated with a well established safety profile. The accessibility and cost of this medication makes phenobarbital a good choice for may patients with seizures. Bromide Bromide has been used to treat seizures since the late 1800’s. It is commonly supplied as a salt with either potassium or sodium. Traditionally, bromide has been compounded into liquid or capsule formulations. However, a potassium bromide veterinary product is now available which comes in flavored chew tablets as well as a butterscotch flavored liquid. Bromide is relatively inexpensive, and it has a broad range of seizure control for dogs. A recent paper reported slightly lower efficacy than phenobarbital at treating all types of seizures. However, potassium bromide may be better than phenobarbital at preventing cluster-type seizures. Bromide is an ion which is freely filtered by the kidneys. It does not undergo any metabolism. However, in patients with a decreased glomerular filtration rate, bromide excretion can be reduced leading to a toxic blood level. The side effects of bromide are similar to phenobarbital. Polyuria, polydypsia, and polyphagia are commonly reported. Sedation, and in particular, pelvic limb ataxia, are common, transient effects of potassium bromide. Because of the extremely long half life of bromide, the sedation effects usually start about 1 month after onset of therapy, and sedation will last for an additional 4 weeks from that point. Bromide can occasionally cause a mild chronic cough in dogs. In cats, a potentially fatal pulmonary disease can occur, so bromide is not recommended in this species. Potassium bromide is a pure salt, so vomiting immediately after ingestion can occur due to direct irritative effects on the gastric lining. Concurrent food administration can lessen this. There are scattered reports of pancreatitis associated with bromide, phenobarbital, and also combined therapy of the two drugs. An excessive bromide blood level can lead to a condition called bromism. Starting doses from bromide can be around 10-30mg/kg/day as a single dose or divided into twice daily dosing. The dose is then gradually adjusted upwards to reach the target blood level. With phenobarbital and bromide, the dose to blood level ratio is approximately linear. Also, a dose of 10mg/pound/day is expected to reach a blood level of 1.0. Monitoring bromide therapy and assessing therapeutic success is challenging because of the degree of patience required. The serum half life of bromide is about 2 weeks with considerable interpatient variability. Because of this property, steady state levels are not achieved until 2-5 months of steady therapy. The earliest that a blood level should be measured in the average patient is at 2 months. The exception would be an extremely sedated patient, where it would be helpful to check if the blood level is excessively high. As sedation is compounded by concurrent phenobarbital therapy, therapeutic levels are reported as 2-3 when used as a monotherapy and 1-2 when bromide is given concurrently with phenobarbital. In patients that vomit excessively from potassium bromide, sodium bromide should be considered. The efficacy is essentially the same, however a 12-15% dose reduction is needed when switching from KBr to NaBr. Bromide is a good maintenance drug for many patients with seizures. The long serum half life limits the usefulness in an emergency setting. Levetiracetam: One of the newer AEDs available in veterinary medicine is levetiracetam (trade name Keppra). This medication is available as tablets, an oral solution, and an injectable solution. It is moderately to very expensive depending on the size of the patient. Levetiracetam is useful in the treatment of any type of seizures, and it is compatible with all other seizure medications. Levetiracetam can be used as the sole anticonvulsant in some patients, but a honeymoon affect with tolerance development has been occasionally reported. Levetiracetam clearance is enhanced when given with phenobarbital, so higher doses of levetiracetam may be needed if giving both drugs together. Levetiracetam is 70-90% renally excreted, so care is needed when using this medication in renal insufficiency patients. The starting dose is 20mg/kg every 8 hours. Because of the short half life, timing of doses is very important. If seizure control is insufficient, increase the dose by 20mg/kg increments every 1-2 weeks until either the seizures are controlled or sedation occurs. Doses up to 70mg/kg are tolerated by most dogs. The literature is limited regarding cats, but it appears to be safe and well tolerated. An extended release formula is available, and preliminary pharmacological research suggests that once daily dosing may be effective. The injectable formulation can be given IV, IM, and subcutaneously. Drug levels can be monitored through Auburn University, but therapeutic range has not been established for dogs. The serum half life is 1.7-4 hours, so steady state is reached after 24 hours of oral dosing. Although extremely safe, CBC and chemistry profile monitoring as for phenobarbital is recommended as we may not know of all possible idiosyncratic reactions to this medication. Zonisamide: Another new AED in the veterinary arsenal is Zonisamide, trade name Zonegran. This is available as capsules and is of intermediate expense. Zonisamide is most commonly used as an add-on treatment with bromide and/or phenobarbital to improve seizure control. Zonisamide can be used to treat any type of seizure, but it has improved ability to control clusters and partial seizures. Occasionally, Zonisamide can be used as a sole anticonvulsant when used in patients with structural brain disease. Zonisamide is 70% metabolized by the liver through an unknown enzyme system, and it is relatively contraindicated in patients with liver disease. As zonisamide is a sulfonamide derivative, it should not be used in patients with known sulfonamide sensitivity. Sedation and transient inappetance are common side effects. Rare, but potentially life threatening idiosyncratic hepatic necrosis has been reported. Starting dose ranges from 5-12 mg/kg BID-TID. Timing is important, and most dogs do well with dosing every 12 hours. In cats, 5-10mg once daily is usually adequate. The halflife is somewhat variable but averages 15 hours in dogs. Steady state is achieved after 3-4 days. Serum levels can be measured through Auburn University, and the half life can be determined using peak and trough levels. The therapeutic range has not yet been established for veterinary patients. CBC and chemistry profile monitoring should be performed as described for phenobarbital. Improving Compliance Once a seizure disorder has been identified, and clinical observation has determined which therapies should offer the best control, the next step is to get the client to follow your recommendations. The first step in improving compliance is to explain the options available and include the client in the decision making process. Topics to include are: expected side effects and duration, cost of drug and monitoring, dosing schedule, and time to reach therapeutic levels. Mentioning the rare complications is important as well. Finally, explain that even with excellent drug therapy, seizure will probably still occur from time to time. How do we tell if the medication is working? First, prior to starting the drug, we should try to determine the seizure frequency and character of the seizures. Having the clients keep a detailed seizure log is extremely helpful to aid in answering these questions. The second factor in evaluating drug efficacy is whether or not we are using it correctly. Each drug has a different half life, dosing schedule, and therapeutic level. Incorrect use will lead to decreased seizure control or excessive sedation. The third consideration is disease progression. If seizure control worsens, it is important to ask ourselves how confident we are in our diagnosis of Idiopathic Epilepsy. What about the side effects? Some AEDs have annoying side effects that can decrease the perceived quality of life at home. Understanding the individual drug sedation protocol is key to helping client’s know what to expect. If sedation persists past the expected time frame, or is so severe that the patient cannot walk or feed itself, then measuring a blood level to see if the target blood level was overshot is indicated. Bromide and phenobarbital notoriously cause ravenous hunger, and this can be a source of extreme stress for owners as well as leading to unhealthy weight gain in some patients. Feeding small meals, more frequently throughout the day can be helpful as can switching gradually to a low calorie or even prescription weight loss diet. It is important that owners avoid using high fat foods to hide the pills and instead try foods like low fat cheese sticks or turkey or soy hot dogs to help prevent weight gain. Polyuria can be managed by limiting water at bedtime and letting the pet outside more frequently during the day.