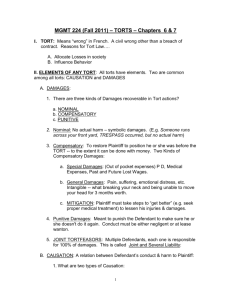

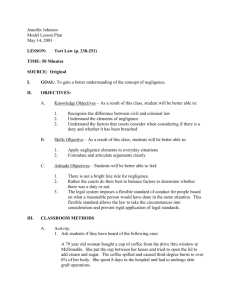

Torts Outline - NYU School of Law

advertisement