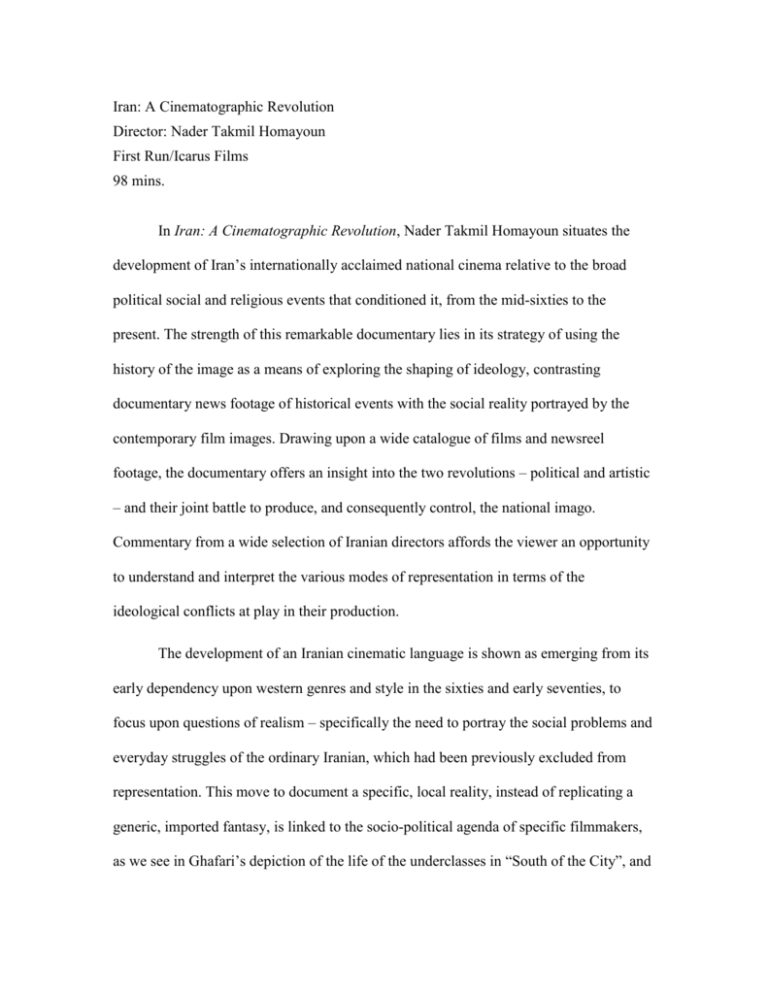

Iran: A Cinematographic Revolution

advertisement

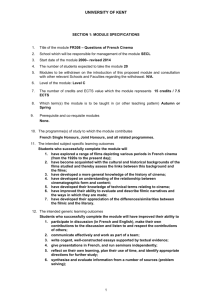

Iran: A Cinematographic Revolution Director: Nader Takmil Homayoun First Run/Icarus Films 98 mins. In Iran: A Cinematographic Revolution, Nader Takmil Homayoun situates the development of Iran’s internationally acclaimed national cinema relative to the broad political social and religious events that conditioned it, from the mid-sixties to the present. The strength of this remarkable documentary lies in its strategy of using the history of the image as a means of exploring the shaping of ideology, contrasting documentary news footage of historical events with the social reality portrayed by the contemporary film images. Drawing upon a wide catalogue of films and newsreel footage, the documentary offers an insight into the two revolutions – political and artistic – and their joint battle to produce, and consequently control, the national imago. Commentary from a wide selection of Iranian directors affords the viewer an opportunity to understand and interpret the various modes of representation in terms of the ideological conflicts at play in their production. The development of an Iranian cinematic language is shown as emerging from its early dependency upon western genres and style in the sixties and early seventies, to focus upon questions of realism – specifically the need to portray the social problems and everyday struggles of the ordinary Iranian, which had been previously excluded from representation. This move to document a specific, local reality, instead of replicating a generic, imported fantasy, is linked to the socio-political agenda of specific filmmakers, as we see in Ghafari’s depiction of the life of the underclasses in “South of the City”, and Shirdel’s (1965) documentary sequence shot on the streets of Tehran, neither of which made it to the screen. The gap between officially sanctioned filmic representations, depicting (westernised) lifestyles of power and affluence, and the everyday reality of the majority of Iranians, is proposed as a key factor in shaping the ‘poetic-realist’ trend that came to characterise the New Wave directors such as Mehrjui, Ghaffari, Kimiai, Golestan, and Kiarostami. The prescient films of Kimiai (‘The Journey of the Stone’) and Beyazi (‘Downpour’) captured the growing mood of political dissent and the increasing emphasis on religion, foreshadowing the imminent 1979 revolution. Homayoun captures the moral backlash against cinema that followed, documenting the burning of cinema houses, while making clear that it was the overtly sensationalist nature of the majority of mainstream films that occasioned this attack. The importance of cinema as an ideological tool, recognised early on by Khomeni (‘we are not against cinema, we are against what is ungodly’) set the stage for the cultivation of a properly Islamic cinema, guided by the Ministry for Cultural Affairs and the Farabi Foundation, giving rise to ‘greenhouse’ or ‘pasteurised’ cinema – with Mehrjui’s ‘The Cow’ serving as the model. The intricate balance between the sanctioned image and its subversion is skilfully brought out by the filmmaker, as he situates the cinematic output relative to the shifts in political and religious boundaries, using newsreel and photographs to document the context within which the directors were working. The 1980-88 war with Iraq is presented as a particularly fraught site of contestation. Homayoun sets news footage of the conflict against official filmic representations that offered a blend of mysticism and heroism designed to rouse citizens to becomes willing martyrs to the cause, balanced by the attempts of film makers such as Naderi to present alternative, unvarnished depictions of the conflict. The final section of the documentary takes on questions of censorship, allowing the post-revolutionary directors such as Makhmalbaf, Naderi, Panahi, Ghobadhi and Bani-Etemad to discuss their own ways of working within the constraints of the new republic. The initial struggle to construct an authentic national imago is reframed as a need to go beyond what has come to define Iranian cinema aesthetics, namely, its use of child actors, the emphasis on traditional values, the depiction of nature, and its strong connections with Persian poetry. Contemporary Iranian films characteristically draw upon the conventions of neo-realism and documentary in order to question the politics of representation, playing with the historical use of the image for ideological ends - both imperialist and revolutionary - as well as its capacity to reflect reality and work as a catalyst for social change. However, this dichotomy becomes the reflexive root of Iranian cinematic practice, as scenes from Makhmalbaf’s ‘Salaam Cinema’ emphasize. The success of the domestic film industry, at home and abroad, is shown to have kindled an infatuation with the film imago, evidenced by the thousands of hopeful starlets that turn up to Makhmalbaf’s open casting session – the same hoards that decades earlier were burning down cinemas now audition as facsimiles of the same Hollywood icons Iranian cinema set out to displace. On the one hand, this speaks to the successful resolution of the struggle to construct a national cinematic identity, as Makhmalbaf claims: “Ideology blinded us – when you take off the blindfold you say “Ah – that’s who I am!” On the other hand, the documentary adroitly shows that although the development of Iranian cinema is closely conditioned by its historical circumstances, the power of the image still remains under the sway of a global politics of representation. Lindsey Hair SUNY Buffalo