How programming language shape interaction and culture

advertisement

“Language exerts hidden power, like a moon on the tides.”

Rita Mae Brown

How programming language influences interaction and culture

By Ivar Tormod Berg Ørstavik

Abstract:

This article illustrates how morphology in programming languages influences interaction

among programmers. To facilitate this illustration three theoretical approaches (Dialogic,

Cassirian and Phenomenological) are presented and contrasted against each other. Based

on this theoretical exploration and analytical tools from dialogic theory an experimental

study is performed. This study experiments with and then exhibit how different type

systems in object-oriented programming encourage and discourage different

programming practices and power structures.

1. Introduction

1.1 An applied linguistic approach to theories of language1

For an applied linguist theories of language are combined with empirical studies. These

syntheses often focus on solving/describing language problems/phenomena from the

‘real’ world and place the theoretical foundation in the background. Such an approach fits

well with the name ‘applied linguistics’. But, it is wrong to conclude that such syntheses

sum up applied linguistics. Applied linguistics just as often focus on and place theories in

the foreground and uses the empirical foundation as a background against which to

investigate and evaluate these theories. Hence, applied linguistics is not just about

empirical knowledge and solving problems: applied linguistics also strives to enhance our

theoretical understanding of language by constantly flipping empirical phenomena and

theory as foreground and background.

Direct comparison of different theories is one way to shed light on both similarities and

differences between theories and the theories in themselves. But, evaluating theories

through abstract or historical analysis alone is vulnerable to the personal, subjective taste

and beliefs of researchers. Therefore, different theories on language should not only be

described against each other, but also against some empirical background. By pulling in a

third party, such as empirical data, a less biased mediator is involved in discussions on

the ‘righteousness’, ‘truthfulness’, ‘usefulness’ or other value of different theories, values

that might elude abstract, historical analysis alone.

In this article I will try to use just this approach to better understand the nuances and

seemingly trivial differences between three related theoretical views on language:

Dialogism2, Cassirer and phenomenology.3 This theoretical analysis will then be

In this article, ’language’ refers to ‘language, language use and communication’.

In this article Dialogism refers to a current, applied Scandinavian school of thought (Evensen 2002,

Linnel 1998). This tradition takes much of its theoretical foundation from Bakhtin’s work.

1

2

1

juxtaposed with an extensive empirical analysis of morphology and power in

programming languages using a dialogic perspective. Based on this empirical analysis

and the preceding theoretical discussion, the article will raise some arguments and open a

discussion on the form and content of the different theoretical views on language.4

2. Theory

2.1 A hidden, historical legacy from Cassirer to Dialogism

‘Tragicomical’ is probably the best word one can use to describe the link between

Cassirer and Bakhtin’s theories. Their common focus on laughter, comedy and carnival

as philosophical subjects is a dominant, direct line between the two. In addition, the need

for contemporary studies to uncover (or rather recover/salvage) such things as ‘Bakhtin’s

verbatim translation of over half a page of Cassirer’s [writing]’(Poole 1998: 543) and

other references of Cassirer’s line of thought in Bakhtin’s works, is a tragic example of

the damning effect external and internal forces in men can have on research.

However, this tragicomic connection is not the only legacy left behind by Cassirer

through Bakhtin. For me as an applied linguist the method Bakhtin adopts from Cassirer

is the most pertinent: historical studies of texts and thought (ibid.:546-47: ‘historicism’).

With Cassirer’s method Bakhtin turns to textual data spanning longer historical periods in

order to understand the emergence of both language and thought and their symbiotic

relationship. “To understand the historical dynamics in [literary-linguistic] systems and to

overcome a simple (and in most cases shallow) mapping of existing styles and how they

replace each other, to historically explain these changes, a review of the speech genres

[…] history is necessary, that more directly, flexibly, and more sharply reflect all changes

that occur in society” (Bakhtin 1998: 7, translated from Norwegian to English by me).

Time is needed to understand languages evolving, and time is here understood in a

loooong, historical sense, i.e. years and centuries, not hours and minutes. It is through this

understanding of the emergent historical dimension of language, a.o., that one can

understand a) how language come to form b) how men form c) their perceptions of

‘reality’ – ecologically. “[The language of techniques] first begins to open up and let go

3

The article will begin with a description of a blurred connection between Cassirer and Bakhtin. This

connection highlights the similarities between the Scandinavian dialogic tradition (represented by Bakhtin)

and Cassirer, a philosopher linked to phenomenology. Second, this article will describe a sociolinguistic

influence on Bakhtin that differs from Cassirer’s approach. This will illustrate a distance on a social axis

between the two theoretical strands. Third, this article will try to place Cassirer and phenomenology along

this same axis. This discussion will help illustrate subtle differences between the three theoretical

viewpoints, a difference having more to do with research agenda and methodological starting point more

than theoretical conclusions.

4

This empirical study will end with an open discussion on whether or not a phenomenological approach

would come to the same conclusions as the dialogical approach illustrated. This would illustrate points of

connection between the two theories. But, of equal importance is the discussion on what points,

theoretically and methodologically, the two theoretical approaches would part and what aspects of the

empirical phenomena a phenomenological approach could capture that has eluded the dialogic approach

taken. Different theories of language and communication will highlight different aspects in empirical

studies, and understanding such differences is of great value to both applied linguistics and discussions on

the theories in themselves.

2

of its secrets when one, even here, goes from forma formata and back to forma formans,

from that which is created, back to the principle of creation.” (Cassirer 2006: 91).

Cassirer and Bakhtin’s historical method has a second, important characteristic: the

historical, textual data selected often exemplifies language revolutions and uses a broad

conception of language (cf. Cassirer 2006, Cassirer’s notion of symbolic forms, and

Bakhtin’s selection of literature). Language development, forms and functions are

investigated through illustrations of change and anomalies, not through descriptions of

systematic evolution of normality in ‘natural languages’. This focus on abnormality

differs from traditional linguistic studies of language development (cf. Chomsky 1965,

Hopper 1987) or classical, philological studies as Humboldt (sited by Chomsky 1965).

Their historical approach is revolutionary rather than stationary, focusing more on

sporadic examples of ‘abnormality’ than on continuous descriptions of ‘normality’ or

‘unity’ in language.

This historical, revolutionary method goes hand in hand with the theoretical stance

Bakhtin and Cassirer takes on intersubjectivity. Common in their understanding of

language is a view of intersubjectivity rather than subjectivity as the driving force behind

language evolution. However, their views on intersubjectivity differ: Cassirer takes a

more abstract, general view of intersubjectivity while Bakhtin takes a very concrete,

personified view; while Cassirer searches for a neokantian Basisphenomena, the

‘Objectivity of the symbolic form’ grounding intersubjective processes5, Bakhtin’s

descriptions seem more content with an open-ended, chaotic picture. But regardless of

their differences, they both present an interactional, historical, intersubjective process

driving language development, a process that is more erratic, incidental and

revolutionary, than ordered, logical and steady.6

5

Each of us speaks his own language, and it is unthinkable that the language of one of us is carried over

into the language of the other. And yet, we understand ourselves through the medium of language. Hence,

there is something like the language. And hence there is something like a unity which is higher than the

infinitude of the various ways of speaking. Therein lies what for me is the decisive point. And it is for that

reason that I start from the Objectivity of the symbolic form, because here the inconceivable has been done.

Language is the clearest example. […] And I believe here that there is no other way from Dasein to Dasein

than through this world of forms.” (Cassirer quoted in Heidegger 1997: 205).

6

In the Scandinavian dialogic tradition few studies use methods that enable a long historical perspective or

revolutionary text focus. While the theoretical dimension of this historical timeline and emergence in

language is well described in models such as ‘the double dialogue’ (Linnel 1998??) and ‘diatope’ (Evensen

2002), these methodological guidelines from Cassirer and Bakhtin are not as evident. When this theoretical

and methodological synthesis is broken in empirical studies, discrepancies between theory and method

might arise. First, macro-historical theoretical perspectives risk being set up against essentially microhistorical empirical data. Second, “only with the coming of ‘mnogoiazychie’, a pluri-lingual environment

(polyglossia), can ‘consciousness be completely freed from the power of its own language and linguistic

myths’” (Brandist 2004: 150 quoting Bakhtin dialogic imagination). Researchers need abnormality and

differences between symbolic forms to create meta-perspectives on language and how it shapes their own

language based perceptions. It can be argued that the contemporary Scandinavian dialogic tradition does

not fully address these aspects in their choice of methods.

3

2.2 Dialogism inspired by the Soviet Union

However, this development in dialogic theory was not only inspired by Cassirer’s view

on language development. “’Marxist understanding of the social-historical process’

[(Iakubinskii 1930-31)] constitute the main source of Bakhtin’s sociological and

historical account of language in his essays of the 1930s.” (Brandist 2004:146). Partially

isolated in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s Bakhtin was both inspired by and

forced to relate his theories to Marxism and strongly socially-oriented views. Cassirer on

the other hand, a neokantian German philosopher, discussed his theories with logically

oriented philosophers heavily preoccupied with individual consciousness and

subjectivity. Although both conclude that intersubjectivity drives language development,

Bakhtin and Cassirer reach this conclusion from two almost diametrical theoretical

arenas.

Common to Cassirer and Bakhtin’s theoretical and methodological approach on language

and its development can therefore be understood to include their historical and changeoriented method and their conclusion on intersubjectivity. But the strong social and

concrete starting point in Bakhtin’s theories seems political and different from Cassirer’s

philosophical and abstract starting point. Bakhtin combined a socialist agenda with

Cassirer’s historicism, “severed Iakubinskii’s argument from its historical moorings, and

incorporated it into an account of literary history with different origins and historical

coordinates” (ibid.: 150).

Another difference between the two approaches is Voloshinov, a contemporary Soviet

scholar to Bakhtin, who “translated intersubjectivity into discursive forms: dialogic

relations” (ibid.: 146). Giving an abstract concept of intersubjectivity concrete

counterparts in various descriptions of ‘dialogic relations’, the dialogic approach thus

enable researchers to more readily identify such phenomena in empirical data from text

and discourse. Building on both historicism and a dialogic twist Bakhtin illustrates in

several studies not only this directions value for theoretical understanding of language,

but, perhaps even more so, the applicable value these ‘nuances’ made for empirical

investigations.

Examples of terms and perspectives that modern dialogism cultivate from this socialist,

Soviet source of inspiration7 are variations on ‘dialogue’, ‘utterance’, ‘sentrifugale and

sentripetale forces of language’, ‘heteroglossia’ and ‘polyglossia’. These concepts and

perspectives have their cousins in other theoretical traditions, such as for example

Cassirer’s, but the socialist agenda underpinning these perspectives and the ‘dialogic’

twist they are given are historically and theoretically quite unique to Dialogism. In this

way the social, dialogic starting point in this theoretical perspective differs from that of

Cassirer.

Bridging empirical data such as text and complex theories of language is no small matter.

Seemingly insignificant ‘theoretical’ differences such as nuances in approach, methodic

7

Not excluding other sources of inspiration.

4

starting point, political agenda and choice of words can greatly impact how empirical

data and theories shed light on each other.

2.3 A subjective presentation of Phenomenology and its time

“In the Logical Investigations [Husserl] conceives of phenomenology as descriptive

psychology [and] analyzes the intentional structures of mental acts and how they are

directed at both real and ideal objects” (Wikipedia 2007). Logic, psychology and analysis

of intentions and mental actions constructed a platform for a philosophical tradition and a

forum in which Cassirer participated, but that Bakhtin only observed. This difference is

not only a historical, geo-political curiosity. Contrary to the socialist8 starting point of

Bakhtin, the phenomenological platform started with the individual: “phenomenology

studies conscious experience as experienced from the subjective or first person point of

view” (Stanford 2007).

Both Dialogism and phenomenology room both the subjective and the intersubjective.

This article does not argue otherwise. However, historically the two traditions’ start off

from opposite directions along this axis. This difference makes their approaches and

preferences to subjectivity and inter-subjectivity differ. This article investigates the

consequences of this diametrical methodological and theoretical starting point when

applied to empirical phenomena. How do a) their different approach to subjectivity and

inter-subjectivity shape b) how dialogism and phenomenology shape c) our perception of

empirical phenomena such as language and its use? To illustrate the difference between

different approaches illumination of empirical phenomena, we will begin by illustrating

how different starting points can color terms and perspectives.

‘Time’ is once more an appropriate example. For Cassirer and Bakhtin their looong

historical perspective was intrinsically part of their understanding of intersubjectivity. On

the other hand, Heidegger, a participant in the phenomenological discussion, “believes

that we […] can only understand the phenomenon of time from our mortal or finite

vantage point” (Alweiss 2002: 117). Taking a subjective, rather than inter-subjective

approach, “time ‘is’ only for a being that lives with an awareness of its own mortality”

(ibid.: 118). This perception of time was based on the necessity of using our death as

individuals, rather than eternity, as an understandable point of departure against which to

understand time (Heidegger 1924, translated by Alweiss 2002: 118).

‘Time’ in this particular phenomenological interpretation, is thus tightly linked with the

‘individual subjective’, both concepts informing the other. However, an individual,

subjective experience of death (and thus time) is no more within our human grasp than

eternity: “death comes from outside and transforms us into the outside” (Satre 1969,

quoted by Alweiss 2002). This critique of an individual concept of time refers to the

scope and boundaries of a subjective approach.

An inter-subjective approach to a similar timeline is however not open for the same

criticism. Even though we may never experience the phenomenon of our own death, we

8

cf. the rights of the collective vs. the rights of individuals

5

can perceive the death of others: we can know and feel quite tangibly what another’s

death means for me and for us. Individual death in general (as abstracted from that of

others) and our own death (as a reflection of others) become meaningful within this

approach. Having a reference for ‘death(s)’ thus gives a reference for a similar timeline the only difference being the starting point on the subjective/inter-subjective axis.

Viewing time from an intersubjective stance highlights the plurality of time. Using a

metaphor from computer science, our ‘environment’ can be understood as

‘multithreaded’, not only ‘single-threaded’. Several independent timelines and flow of

control run concurrently, parallel and cross each others’ paths.

A subjective, individual approach might also eventually in their argument support a

multithreaded view of time and a view that such timelines cross, overlap and interact with

each other. But, time’s multiplicity and heterogeneity would not be as glaringly apparent

from an individual, subjective stance as it is from an intersubjective approach. The

methodic starting point establishes a conceptual priority that consequently shapes our

theoretical perceptions.

Therefore, understanding the priorities of different theories is especially important in

empirical studies of for instance language. In such studies only the tip of the iceberg of

theoretical conclusions makes it to the surface in the sea of empirical data, the rest being

weighted down by the priority of other conclusions.9 But, crucially, this knowledge is not

only important in order to understand empirical phenomena. Flipping the coin, the reliefs

synthesized of theory and empirical data can also be read as a topographical map of

theories priorities. Hence, both empirical phenomena and theories illustrate each other.

2.4 The semantics in dialogism – dialogic semantics

Focusing explicitly on the social character of language, dialogism has developed several

analytical concepts to illuminate the intricate, reciprocate relationships between language,

our thinking, interaction and culture. A central concept within these theories is the social

dimension of utterances, texts and words (Bakhtin 1986). "[Language] is populated –

overpopulated – with the intentions of others "(Bakhtin 1981: 294), and when we

perceive and express reality with words in any language, we use the language of others in

order to compose our own perspective on reality. Thus, in dialogic studies (Evensen

2002, Bostad 2005), our thoughts, actions and ontologies are composed as ‘polyphonies’

(Bakhtin 1984) or ‘refractions’ (Bakhtin 1981: 300, cf.276) of other's voices.

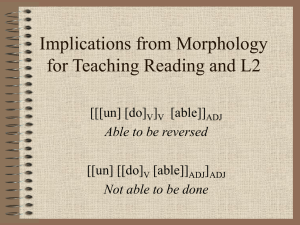

When viewing language and our perception of the world primarily as social references,

'semantics' is seen in a new light. Rather than categorizing semantic relationships

between say a word and a physical world or a universal logic (figure left), the meaningful

references or ‘semantic relationships’ in words become their relationships to other social

actors and their texts, i.e. their 'inter-textual' role (figure right). The meaning ascribed to

words are not viewed primarily in categories such as ‘information’ or ‘indices’ to

9

In dialogism this multithreaded timeline is very evident in say models of overlapping, interacting

utterances, dialogues, discourses, languages, cultures, etc. The inter-subjective timeline permeates the

dialogic perspective.

6

domain-specific logics or lexica; the meaning-potential of words are viewed rather as

social ques or voices of others.

a tree

a tree

a tree

a tree

a tree

a tree

a tree

a tree

2+2=4

2+2 = 4

2+2=4

2+2=4

e=

mc 2

2+2=4

2+2=4

2+2=4

2+2=4

Figures: The two simplistic models try to present the difference in focus and taxonomy of

the two research approaches; the models do not present the approaches in themselves.

Left side illustrates simplistic models of how a subjective, individual approach

exemplifies index and logic oriented semantics. Right side illustrates how an

instersubjective approach can exemplify social, inter-textual semantics. The arrows

indicate the meaningful relationships that the different semantics focus on.

Viewing language and words neither as individual property nor asocial realities, social

forces become a primary reality in language. Social structures are seen not only side by

side with language, but also as within language itself. Core aspects of language are

viewed as sedimented patterns of interaction. Several separate linguistic traditions pick

up on this point: Socio-constructionistic genre theory understands genres as ‘recurrent

rhetorical actions’ (Miller 1984, Berkenkotter 1993). Other research on

‘grammaticalization’ tries to describe how “yesterday’s pragmatics is today’s syntax”

(Givon 1979).

In order to understand the make-up of languages, it therefore becomes essential to

understand the social interaction and relationships that languages are built up alongside.

Interaction among language users, patterns of recurring rhetorical actions, practices, and

other social dynamics all become dimensions potentially reflected within language. And

since these languages are the ones we in turn use to form our individual utterances and

perspectives on the world, the spiral is completed: social patterns of interaction shape

language that shape individual actions and thoughts that in turn shape social interaction.

Turning to programming languages, a dialogic approach and social semantic taxonomy

can seem irrelevant if programming is deemed solely utilitarian and asocial. Social

dogma and stigma greatly encourages such a view on programming languages, and if a

subjective approach and a conventional semantic orientation is taken towards this

particular, empirical domain, it is more than likely that these views will only be enforced.

7

However, though quite common, an asocial perception of programming languages and

their use is not the only meaningful take on the subject. Programming can also be

understood as highly social as for instance the open source movement has demonstrated

to its fullest. Software is an inter-text, and the words of programmers reflect not only

logical functionality, but also echo the voices of other programmers. The more complex

and socially entangled these inter-textual programs become, the more important it

becomes to understand this social dimension of programming languages.10

3. Empirical analysis

3.1 Scope of analysis

Morphology in object-oriented programming is a complex phenomenon, and the

empirical scope of this study must therefore be specified and constrained.

The first constraint regards the kind of words to be studied. In object-oriented

programming there are several ways to compose and use words. First and at the core is a

set of ‘reserved words and operators’ defined and made significant by the compiler,

interpreter and/or platform. These words constitute a lexical skeleton in all objectoriented languages. Second and fleshing out a body around this skeleton is a set of words

that we will here describe as ‘types’. In this study we use a broad definition of types to

mean all kinds of words that can be defined and referenced by any user alike. Third and

within the reach of this body of words are other similar mechanisms to describe and refer

to functionality. Relevant examples of such mechanisms are remote objects/methods (as

in CORBA, RPC and RMI) and web services.

In this study we will only focus on the second category: ‘types’. The reason for excluding

the first category, the lexical core, is that these words are rarely, and if so very limitedly,

defined by ordinary users. The reason for excluding the third category, similar

mechanisms, is that these methods primarily use syntactical, not morphological forms to

express references to other programmers’ texts.

Secondly, there are several nuances in the way types can be defined and referred: In

Python types can be structured as both methods and classes, while in Java all types must

be defined as classes; import and package statements can shorten type-names; object

variables at different levels can function as ‘proforms’ or morphological placeholders;

inner classes are stored differently than normal classes; etc. etc. However, all these

nuances adhere to the same overall morphological form. We will therefore not address all

such details, but only the general, overall structure of type references.

Third, this study approaches type morphology with a dialogic perspective and a social

semantic taxonomy. Therefore, this study will primarily focus on the socially oriented

actions and practices that directly surround the morphological forms, and secondarily on

the symbolic morphological forms as such. This approach differs substantially from

10

So, in order to fully understand the reciprocate influence between programming languages and

programmers’ actions, thoughts and ontologies, it is crucial to at the same time understand the reciprocate

relationships between programming languages, programmer interaction, and culture.

8

traditional linguistic descriptions such as BNF and traditional linguistics that derive their

descriptions of morphology primarily from the symbolic forms.

With this scope, this article analyses two different morphological forms in object-oriented

programming: ‘pc-based morphology’ in Java and Python and ‘web-based morphology’

in an experimental programming language theJ (Ørstavik 2006).

3.2 The path to the words of others: describing pc-based morphology

When writing a program in Java or Python, a programmer uses words that other

programmers have defined as underlying resources in his own text. As mentioned earlier,

these words can be operators and ‘reserved words’ defined by the programmers who

made the compiler, interpreter and/or platform (figures: grey), or types defined by any

other programmer (figures: italic). These words are fundamental and indispensable for all

meaningful program texts.

A Java class called HelloJDOM.

import org.jdom.*;

public class HelloJDOM {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Element root = new Element("GREETING");

root.addChild("Hello JDOM!");

Document doc = new Document(root);

org.jdom.output.XMLOutputter output = new org.jdom.output.XMLOutputter();

try {

output.output(doc, System.out);

} catch (Exception e) {

System.err.println(e);

}

}

}

import xml.dom.minidom

A Python module called minidomPrinter.

def printDocument(text):

dom = xml.dom.minidom.parseString(text)

print "<html>"

for line in dom.getElementsByTagName("line"):

print "<p>%s</p>" % getText(line)

print "</html>"

def getText(node):

text = node.childNodes[0]

if text.nodeType == node.TEXT_NODE:

return text.data

return ""

document = "<text> <line>hello!</line> <line>and good bye..</line> </text>"

printDocument(document)

Type names (such as org.jdom.Element in HelloJDOM and xml.dom.minidom in minidomPrinter)

are always path-relative in Java and Python. Path-relative means that all type references

depend on the context of a path delineating a certain group of texts, and type names must

be interpreted within this inter-textual context. The act of wording type references is

therefore not only to a) explicitly formulate a type name consistent with a morphological

pattern. Implied in this act are also the acts of b) obtaining a resource (for instance

9

downloading a .class- or .py-file) in which another programmer has defined the type and

c) updating the path settings (i.e. CLASSPATH or PYTHONPATH) to associate words with

resources. PC-based morphology can thus be seen as a compound act: a) write a word, b)

obtain the word text, and c) update the path on your PC.

This individual, compound act of using other programmers’ words is not limited to a

single step. A programmer can use another programmers’ word that in turn uses yet other

programmers’ words, etc. etc. The morphological system thus creates relationships

between programmers that span several individual words and actions.

class

Cla

Clas ssA {

sC c

Clas =

sE.d

}

o();

}

class

Th

while ing {

(…)

...

class C

lass

ClassD B {

d=

ClassC

.work();

}

class

St

while range {

(…)

class

class

Some} ...

class

St wh

{ wh Strange

ile (…

{

while rangile

e (…

)

... { )

(… cla

...

... } ) ss Strang

}

while

e{

}

(…)

...

class

}

Ot

while herE {

(…)

...

}

}

}

class

C

while lassE {

(…)

...

class MyClass {

ClassA a =

ClassB.work();

}

}

class

C

if (…) lassC {

...

class

C

for (… lassD {

)

...

Figure: Words are interpreted in an inter-textual context.

In principle, and contrary to popular belief, words such as types in a program text are

therefore not specific to one particular interpretation: program words should not be

mistaken for fixed indices to predetermined, universal functionality. The meaning of a

word such as a type name must be determined within a path, and setting up different

paths around the same program text thus allow for different interpretation of the same

words.11 Program words rely on each other in order to function. Hence, program words

can be viewed as inter-reliant voices that need each other in order to make sense and that

echo across inter-textual webs of words. Only when situated in inter-textual environments

enabling concrete interpretation of words do the texts become programs and start (to

make sense).

?

?

?

class MyClass {

ClassA a =

ClassB.work();

}

?

Figures: Undetermined meaning potential in program words.

11

If this path is broken, problems occur, and broken paths are the source of much aggravation.

10

3.3 Social interaction and dynamics of pc-based morphology

The value and usefulness of using others’ words cannot be overstated. To be able to

quickly and simply instantiate objects and invoke methods that other programmers have

spent countless of hours developing is as enabling in programming as the concept of a

round leather ball is in soccer. Also, to be able to delineate a space in which these words

can be used with a specific path setting does as much for programmers as the concept of

an enclosed pitch with two goals does for soccer players.

The reason, as might be guessed from the soccer analogy, is that this morphological act

enables positive and competitive interaction among programmers. By rounding up

programmable thoughts in types easily referable as words, a programmer can build his

game with the input of other programmers working as his team mates. Switching to the

social semantic taxonomy of dialogism, a programmer can construct his perspective on

the world reusing ‘fractions’ of other programmers’ code. The previous examples

HelloJDOM and minidomPrinter can thus be seen as textual, programmed compositions or

‘polyphonies’, where meaning is not just an individually formed idea, but a product or

mosaic of social collaboration in a cultural sphere.

}

}

class

C

if (…) lassC {

...

class

Cla

Clas ssA {

sC c

Clas =

sD.d

}

o();

class

Th

while ing {

(…)

...

class

S

while trange {

(…)

class

clas

Som } ...

class

e { w s Strang

S whi

e{

hile (…

while trangle

e (…

)

{

)

...

(… cl

...

... } ) ass Strang

}e

while

}

{

(…)

...

class

}

Other

while

E{

(…)

...

}

}

class MyClass {

ClassA a =

ClassB.work();

}

class

C

for (… lassD {

)

...

}

class

C

while lassE {

(…)

...

class C

lass

ClassD B {

d=

ClassE

.work()

}

;

However, not all that glitters is gold. Several social, technical, ethical and practical

concerns are associated with pc-based type morphology.

First, a well known ethical concern relates to ‘licensing terms’. When a programmer

chooses to use another programmer’s word, he also presupposes that a text defining the

word must be added to the path. A programmer doing act a) also implies doing b) and c).

But, linked to these underlying texts are ethical, legal, commercial, political and cultural

terms and licenses. Using another programmer’s word therefore presupposes accepting or

breaking the terms of both the words directly used and all the words that these words

iteratively use. “[Words are] populated with the intentions of others” [1], and in

programming these intentions are long chains of both technical functionality and social,

commercial and cultural terms and agendas.

11

As in soccer, the social game in programming is played to win. Using the words of others

means in programming, as in for example academia, to accept the passes from certain

players and choose sides. The programmer behind HelloJDOM and minidomPrinter has in

effect chosen to side with the teams at ‘java.sun.com’, ‘jdom.org’ and ‘python.org’.

These teams have their own agenda and terms associated with their words, and using

these teams’ words involves to some extent accepting and pushing their agenda.

A second well known practical, technical and social concern relates to chained

dependencies between words. Building on the minidomPrinter example, a new program

text called printUser is set up to reference the minidomPrinter. This program text uses

words to directly refer to a printDocument function from minidomPrinter.

from minidomPrinter import printDocument

document2 = "<text> <line>hello again!</line> <line>ta ta..</line> </text>"

printDocument(document2)

A Python module called printUser.

In order to interpret the words in printUser, we need to see it in an inter-textual context. In

printUser printDocument is another programmed utterance. In order to interpret printUser,

an inter-textual context must be set up in which printDocument means some thing (i.e. text):

b) obtain a file matching this description (the above minidomPrinter is a possible, but not

compulsory alternative) and c) update the PYTHONPATH settings to include this file. If

minidomPrinter described above is used, it references xml.dom.minidom. Therefore, if this

interpretation of minidomPrinter is used, the inter-textual context of printUser will now also

imply xml.dom.minidom. Thus a path with both a working definition of minidomPrinter and

xml.dom.minidom must be set up. This contextual relationship from printUser, minidomPrinter

to xml.dom.minidom constitutes a dependency chain.

}

}

class

Th

while ing {

(…)

...

class

S

while trange {

(…)

class

clas

Som } ...

class

e { w s Strang

S whi

e{

hile (…

while trangle

e (…

)

)

... {

(… cl

...

... } ) ass Strang

}e

while

}

{

(…)

...

class

}

Other

while

E{

(…)

...

}

class

C

for (… lassD {

)

...

}

}

class

C

while lassE {

(…)

...

}

p a cka g

e

class E org.jdom;

lement

{

while(.

..)

...

class

C

for (… lassA {

)

...

}

class

C

while lassB {

(…)

...

}

p a cka g

e

class E java.lang;

xceptio

n{

while(.

..)

...

class HelloJDOM {

org.jdom.Element...

…{

Exception ...

}

Figure: Illustration of chain of dependencies around HelloJDOM.

As described in the above example a programmer using another programmer’s words will

have to weigh the benefits of using the word against the cost of obtaining files and setting

12

up a path needed to realize a certain interpretation of these words. If using a certain word

demands obtaining dozens of files from different locations in separate steps, odds are that

this word will not be used as often as other alternatives requiring less work. In addition to

these practical concerns, programmers place a certain amount of trust in each other when

they use each others’ words and types. Several technical and practical barriers stop

programmers from knowing exactly what happens when the flow of control passes into

an externally defined word in their programs. This lack of insight applies even more so

when flow of control iteratively are passed to words within words. If the programmer

does not trust other words with this control, he probably will not use them. Chains of

dependencies thus also entail trust issues.

PC-based morphology enable the programmer to only perform act a) for only the first

step, but in order to maintain control over the inter-textual context in which his program

should run, PC-based morphology specifies that a programmer must perform acts b) and

c) for all iterative steps in the dependency chain. A programmer may therefore get an

infinite, illegal or broken path thrown into the bargain when using a simple word. His

choice of words is therefore not only concerned with the words technical qualities, but

also their ensuing practical tasks, ‘licensing terms’, his trust in them, and other social

constraints.

3.4 Second and third party words in pc-based morphology

Because of these practical, social and ethical concerns, Java and Python platforms are

distributed with a standard library of words and standard path settings. Distributing the

language in this manner establishes in practice a ‘standard inter-textual context’. A

programmer can anticipate that words from these libraries such as xml.dom.minidom and

java.lang.Exception are always within the inter-textual contexts, while words such as

org.jdom.Element and minidomPrinter are not. This segregates words within and outside the

standard library into second and third party words respectively: when referring to second

party words (a2), a programmer can presume that actions (b_ and c_) will not be needed;

when referring to third party words (a3), a programmer can presume that actions to

establish an inter-textual setting (b3n and c3n) are needed, and in all contexts were his

programs/words are used.

These practical and social concerns play an important role in shaping program literature.

A programmer using another programmer’s words orients not only towards the current

program text and its relationship to prior program texts or types. The programmer of

n

n

HelloJDOM implicitly makes the choice to perform acts (b3 and c3 ) surrounding

org.jdom.Element not only for himself and his own program, but also for any other user or

programmer who wants to use HelloJDOM as an application or type. On the other side, the

programmer of minidomPrinter chooses words such as xml.dom.minidom that with reasonable

certainty can be assumed to be part of later users ‘standard inter-textual context’.

Therefore, minidomPrinter does not place the extended burden on future users of this word

that HelloJDOM does.

This future burden of using a program text is very important in programming. A current

program text will potentially establish links to other program texts. Thinking ahead and

13

‘addressing future utterances’ is sometimes as vivid in many program texts as

programmer’s awareness of already existing program texts.

Because of these social, practical and ethical concerns related to path-relativity of

program texts that 1) have been written, 2) are being written, and 3) might be written, a

‘centripetal force’(Bakhtin 1981: 270) in languages using pc-based morphology emerges.

Because the use of second party words (a2) has so many clear advantages over

technically similar third party alternative words (a3), both for present and future users,

programmers flock towards the use of second party words. The social, practical and

interactional structure of path-relativity combined with the distributors’ ability to set up a

default inter-textual context thus gives a clear home-court advantage for the social groups

uttering second party words over technically equal or perhaps even better alternatives

from third parties.

On Ubuntu (2006) there is a platform tool to ease the practical task of obtaining files and

updating path settings: apt. With tools such as aptitude, Ubuntu offers everyone the

ability to semi-automate the process of establishing new inter-textual environments for

both Java and Python programs via the Internet (b and c). However, these tools are also

shipped with a standard setting, mainly due to concerns of trust. Therefore, even though

apt makes several steps as to simplify the practical tasks of b) and c), the process is only

partially automated and still specifies a ‘standard inter-textual context’. Ubuntu does

therefore not alter the pc-based morphology in its programming languages, but mainly

complements it with a web-based platform.

3.5 TheJ experiment and URL-types: Actions shaping morphology

Our informal experiment started with the development of a platform for programming

multi agent systems in Java (Ørstavik 2005). One of the core issues we faced in this work

was the need for different agent programs to interact with each other using the Java

language as medium, while at the same time maintaining their ability to function

autonomously in individual inter-textual contexts.

Due to the make up of the Java language morphology a problem quickly arose in our

project. When one agent wants another agent to respond to a request, they need to involve

words/types that are part of one agent’s inter-textual context, but not the other’s. There

are many known mechanisms to work around this problem: type definitions can be

passed directly between agents, or one agent can tell another agent to alter its path

settings. However, such mechanisms provide alternatives to type morphology that make

program texts more difficult and heavy-handed to read and write. Further, the problem of

extra-contextual words/types in multi agent systems is in principle the same practical,

social and technical problem concerned with PC-based morphology described earlier.

To tackle this problem, we therefore started looking more closely and creatively at type

morphology. We found that the morphological forms quite easily could be changed so to

enable us to reference extra-contextual types and tackle chained dependencies between

such types. Based on the Java language we developed an experimental dialect called

‘theJ’ (Ørstavik 2006) that a.o. extended the PC-based morphology to also allow for

14

types to be referred to as URLs (URL-types), an extension of the existing morphological

forms.

A theJ class called thej.ExampleTwo.

package thej;

import ftp://213.221.2.15/consult/EAMKA_02_05/client/lib/jdom-1.0.jar/org.jdom.*;

import ftp://213.221.2.15/consult/EAMKA_02_05/client/lib/jdom1.0.jar/org.jdom.input.SAXBuilder;

public class ExampleTwo {

public static void main(String[] args) {

http://the.hist.no/thej.ExampleOne parserA =

new http://the.hist.no/thej.ExampleOne("<b>", "</b>");

SAXBuilder parserB = new SAXBuilder();

try {

parserB.build(args[0]);

} catch (JDOMException e) {

System.err.println(parserA.taggThis(e.getMessage()));

} catch (Exception e) {

System.out.println(e);

}

}

}

Figure: To run this theJ program,

1) download http://the.hist.no/CoreClasses/agentcore.jar,

2) run java -jar …/agentcore.jar http://the.hist.no/ thej.ExampleTwo

3) hope that the system is up and running.

http://ntnu.no,

and

The implementation of URL-types (Løkke 2005) extends both the front- and back-end of

the Java type system: front-end type names can be written echoing complete URLs, for

instance as http://www.jdom.org/jdom.jar/org.jdom.Element, and back-end the compiler and

platform is extended so as to locate, download and utilize program files found using the

URL-information in the URL-type name from the web.

The principal consequence of this change in morphology is primarily linked to the

perception of inter-textual context and actions to control path (b and c). The path is no

longer pc-oriented; the path is web-oriented echoing a protocol that describes how

programmed words can be exchange both within and across different computers. The

underlying compiler, interpreter and/or platform can thereby be told to relate to words on

the web, potentially using the web to automate the tasks b) and c) completely, even in

chained dependencies. Using a symbolic, morphological form to move actions into

morphology as described is making “today’s pragmatics tomorrow’s syntax” (Givon

1979).

However, this move leads to problems with security and a series of primarily social and

trust issues when the now quite centralized control over programmers’ inter-textual

context is lost. Possible solutions to these security problems exist, but have not been

implemented. These issues need to be explored before widespread use of web-based

morphology can be supported. But, this experiment is not about producing a new

programming language; the primary goal of this study is to learn more about the

dialectics between human minds and languages.

15

By setting up a contrasting example this experiment illustrates both 1) how existing

morphology tacitly may have guided our minds and perceptions and 2) how we can think

of program words in new ways.12 This contrasting image creates a ‘hindsight’ view of

current pc-based morphology, a perspective that is very difficult to achieve only having

experienced existing programming language morphology. By exploring new possibilities

limits in existing technical framework and mindsets highlight such phenomena as second

and third party status, and the centrifugal power they bring with them. Exploring

alternative, exotic linguistic forms made me aware that I was continuously checking the

standard library for words, even when I already knew better suited third party

alternatives.

4. Conclusion

4.1 How theory has informed our empirical understanding

Applying this dialogic perspective to programming language should not be read as an

attempt to capture a somehow ‘truer’ description of the world of programming. It is not.

Using a theoretical perspective is a strategic choice taken in order to shed light on certain

aspects or dimensions of phenomena that other theoretical approaches might miss. In this

study the ‘new’ phenomena captured are how certain morphological forms can cluster or

disperse certain patterns of interaction, and how this effect can be seen as crucial for how

languages are shaped and made to use.

The ‘new’ phenomena captured can be described as 1) a hindsight view of current

practices and 2) an insight into what might come. The first, our hindsight view has

already been extensively described in the analysis chapter and will not be pursued further.

However, a few words can still be said about the second.

The difference between pc-based morphology and web-based morphology is both

technically and conceptually similar to the difference between pc-based and web-based

file systems for ordinary text documents. The sentrifugal power unleashed with the

advent of the Internet in the last decade has yet to be fully unleashed in programming

languages. This study shows that incorporating URL into programming languages is

simple to implement technically. This study also shows that the concept of URLs in

program texts is simple to grasp for individuals. However, it remains to be seen if the

potential sentrifugal powers unleashed with such language use can be balanced properly

in social interaction, especially with regards to security and issues of trust.13

Having tested URL-types in action, what is most striking is the realization of the still

untapped potential of ‘third party programming’ (i.e. the strength of the sentrifugal

power). The new morphological way of wording and seeing types encourages us to focus

12

Since this experimental language has not yet accumulated a big body of interaction and practice,

empirical data about interaction with URL-type is fairly limited. The data is constricted mainly to

experiences of a couple of programmers related to the project and the subjective interpretations of our ‘old’

pc-based practices viewed in the light of a new morphological concept.

13

It can be argued that empirical experience with the Internet in general and for instance search-engines

and Internet banking in particular suggest it will. But I know of no full-scale programming language in use

based on web-based morphology.

16

on the use of third party words, to widen our vocabulary and to extend our repertoire of

voices. This has directed our research against creating tools and services to support this

form of interaction among programmers, directing our attention to wikis for writing

program text directly online, web-based compilers and search engines for programming

texts. Such resources are necessary to fully support web-based morphology, but since this

work has just begun, our perception of the world with web-based morphology is still

misty.

4.3 How empirical study has informed theoretical understanding

The Marxist social agenda and theoretical view underlying the dialogic tradition of the

1920-1930’s Soviet Union and Bakhtin’s theory of language can clearly be seen as

reappearing in this study. This was not the original intent of the author and not fully

understood until very late in this study, as can be seen in an earlier version of this study

(Ørstavik 2006 ECAP).

The social agenda finds a clear philosophical ally in the open source movement. Both the

dialogic perspective and the open source movement advocate freedom and openness of

language use, implicitly or explicitly invoking socialist slogans such as ‘power to the

people’ etc. However, an interesting finding in this study is that ‘open source languages’

such as the liberal Python on Ubuntu employ the same centripetal forces to almost the

same extent as commercially owned languages. This illustrates that power is not only

accumulated for monetary ends.

The social agenda in the dialogic tradition, an agenda that neither Cassirer nor

phenomenology theories use as their starting point, thus shapes my perception of

programming languages and their morphology in a way that I do not believe a more

subjective study would do. Assuming that a phenomenological or Casserian study would

stand out similarly against similar empirical backgrounds would be to underestimate the

consequences of the subtle, historical differences between these theories. Thus, both

theoretical differences and the findings of this particular empirical study suggest that

Dialogism should be understood as more than a subset of phenomenology.

References

Alweiss L. (2002). Heidegger and ‘the concept of time’. History of the human sciences, vol.15, no.3, 117132 (London: Sage Publications).

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). Discourse in the novel. (In Emerson C. and Holquist M. (trans.): The Dialogic

Imagination: Four Essays. Austin: Texas University Press.)

Bakhtin M. M. (1986). The problem of speech genres. (In McGee V. (trans.): Speech Genres and Other

Late Essays. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.)

Bakhtin M. M. (1984). Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics. Emerson C. (trans.). Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press.

Bakhtin M. M. (1998). Spørsmålet om talegenrane. Slaattelid R.T. (trans.). Norway: Ariadne Forlag.

Berkenkotter C., Huckin T. N. (1993). Rethinking Genre from a Sociocognitive Perspective. Written

Communication, 10, 475-509.

Bostad F. et. al. (Ed.) (2004). Bakhtinian Perspectives on Language and Culture: Meaning in Language,

Art and New Media. (New York: Palgrave MacMillan)

17

Brandist, C. (2004) Mikhail Bakhtin and early Soviet sociolinguistics. In: Proceedings of the Eleventh

International Bakhtin Conference. Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba (Brazil), pp. 145-153. ISBN

859043981X. http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/archive/00001115/

Cassirer E. (2006). Form og Teknikk. (In Folkvord I. (trans.), Hoel A.S.: Form og Teknikk: Utvalgte

tekster, 87-142 (Oslo: Cappelen Akademisk Forlag)

Chomsky N. (1965). Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-53007-4.

Crowley T. (1990). That obscure object of desire: a science of language. (In Joseph J. E. & Taylor T. J.

(eds.): Ideologies of Language, 27-50. London: Routledge.)

L. S. Evensen (2002). Convention from below: Negotiating interaction and culture in argumentative

writing. Written Communication 19(3), 382-413.

Givon (1979). On grammar. (Sited by Faarlund J. T. (2002). Grammatikalisering av ordstilling. (In Moen I.

et.al.(ed.) (2002). MONS 9 - Utvalgte artikler fra Det niende møtet om norsk språk i Oslo 2001. Oslo:

Universitetet i Oslo)).

Gosling J., Bracha G., Joy B., Steele G. L. (2000). The Java Language Specification: Second edition.

(Boston: Addison-Wesley)

Heidegger M. (1997). Appendix IV: Davos disputation between Ernst Cassirer and Martin Heidegger. (In

Heidegger M., Taft R. (trans.): Kant and the problem of metaphysics, 5.ed., Bloomington: Indiana

University Press)

Hopper P.J. (1987). Emergent Grammar. Berkeley Linguistics Society(13), 139-57.

Lindholm T., Yellin F. (1999). The Java(TM) Virtual Machine Specification (2nd Edition) (Paperback)

(Boston: Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co.)

Linell P. (1998). Approaching dialogue: Talk, interaction and contexts in dialogical perspectives. (John

Benjamins Pub Co.)

Løkke J. (2005). Implementing URL-types in Java. (Trondheim: HiST)

Miller C. (1984). Genre as Social Actions. (In Freedman A. and Medway P. (ed.) (1994). Genre and the

new rhetoric. London: Taylor & Francis.)

Poole B. (1998). Bakhtin and Cassirer: The Philosophical Oirigins of Bakhtin’s Carnival Massianism.

South Atlantic Quarterly 97:3/4 (Duke University Press).

Python (2006). The Python Programming Language. Retrieved June 20, 2006 from http://www.python.org/.

Saussure F. (1916). Cours de Linguistique Générale, Payout, France. (Eng. ed.: The Philosophical Library,

1959; McGraw-Hill, 1966.)

Ubuntu (2006). Ubuntu. Retrieved June 20, 2006 from http://www.ubuntu.com/.

Wikipedia (2007). Phenomenology. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved March 1, 2007 from

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phenomenology

Stanford (2007). Phenomenology. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved March 1, 2007 from

plato.stanford.edu/entries/phenomenology

Ørstavik I. T. B. (2005). Designing multi agent systems using Java as an Inter-Program language. (Paper

presented at JavaZone 2005:

http://www3.java.no/JavaZone/2005/presentasjoner/IvarOrstavik/html/Ivar_Orstavikjavazone2005.html)

Ørstavik I. T. B. (ed.) (2006). Site of theJ programming language. Retrieved June 1, 2006, from

http://the.hist.no.

18