Week 5: Nephrolithiasis

advertisement

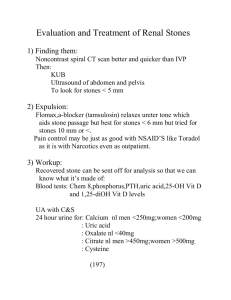

NEPHROLITHIASIS Jacqueline Satchell-Jones, M.D. WEEK 5: 01/31 – 02/04/05 Learning Objectives: 1. Describe the historical, radiographic, and laboratory features consistent with kidney stone 2. Describe how metabolic work-up differs in a patient with initial vs. recurrent stones Editor’s Note: A special thank you to Rebecca Brienza, MD, who was the original author of this chapter, which has been adapted here. CASE ONE: Mr. Stone is a 37-year-old Caucasian truck driver who presents to you with sudden onset of severe right flank pain that travels to his lower abdomen and right groin area. He states that it began two days ago and he has been experiencing waves of nausea, but no vomiting. He cannot recall any trauma. He denies any change in his bowel habit, but does note mild dysuria and occasional urinary frequency. The pain does not change with position or breathing. He took a few acetaminophen without pain relief. He is mildly obese and has GERD, hypertension and diabetes. His medications include hydrochlorothiazide, metformin, vitamin C, and antacids. He denies having any prior gastrointestinal problems, no surgery, and no urinary tract infections. He remembers having similar pain at age 20 but did not see a doctor for it. You believe this patient has kidney stones and send him to the lab for a urinalysis. Questions: 1. a. Explain what features of the patient’s history and presentation are consistent with nephrolithiasis? The cardinal manifestation of renal colic is excruciating unilateral flank pain or lower abdominal pain of sudden onset, not related to any precipitating event (such as muscle strain or trauma, malignancy), not relieved by postural changes or over the counter pain meds. With the exception of nausea and vomiting, GI symptoms should be absent. The pain sometimes radiates to the lower abdomen and ipsilateral groin. If the stone is distal, the patient may have GU symptoms such as dysuria, frequency, urgency, bloody urine, etc. b. What else should you consider in the differential diagnosis for this patient and would it be different if this patient were a woman? One needs to consider in the DDx for this patient the following: hepatitis, pancreatitis, appendicitis, gallstones, hernia, diverticulitis, and blockage in the intestine, AAA, testicular or prostate pathology. If this patient were a woman, you must do a pelvic exam (and a urine pregnancy test) to evaluate for, gynecologic pathology such as ectopic pregnancy, PID, ovarian torsion, and ovarian cyst. c. Explain what you will be looking for in the urinalysis, and why? Findings to look for on the urinalysis include: microhematuria (1/3 of patients with kidney stones do not have blood); urine pH suggests the type of stone that may be present (pH<7: uric acid or cystine stones; pH>7: infection, calcium phosphate/struvite stones). Infection should also be ruled out. Limited pyuria is common with stones but, in the absence of bacturia, is generally not indicative of a UTI. CASE ONE CONTINUED: The patient returns from the lab with the urine dipstick showing 2+ blood and a pH of 8.0. The micro showed >100 RBC, 10-15 WBC, and few bacteria. Urine culture is pending. 2. How would you confirm your diagnosis? Confirm kidney stone with an imaging modality, of which there are several, each with advantages and disadvantages: This patient’s urinalysis is alkaline which may suggest a calcium stone, which would appear radio-opaque on plain X-ray. The limiting factor with plain film is that the sensitivity is poor (about 50%) due to poor visibility from stool and bowel gas. Prior to non-contrast helical CT, IVP was considered the definitive study to confirm kidney stones. IVP has high sensitivity and specificity, provides information on anatomy and functioning of the kidneys; however, it requires use of IV contrast with risk of nephrotoxicity. IVP does not detect non-GU pathology and may not produce a filling defect if non-obstructing radiolucent stones are present. This patient has diabetes and is on metformin and a diuretic, and so IVP would not be a good choice for him due to the risk of fatal metabolic acidosis and an increased risk of nephrotoxicity. If one needs to do an IVP (i.e. CT not available), the patient should be well hydrated, metformin needs to be stopped 24 hours prior to the planned date and restarted 48 hours after this procedure. An ultrasound is useful to rule out obstruction or hydronephrosis and is usually readily available. It is sensitive in identifying renal calculi but not ureteral stones, which are more likely to be symptomatic. Non-contrast helical CT is the imaging study of choice for this patient. It is fast, accurate, readily identifies all stone types in various locations, and is safe. Its sensitivity and specificity is over 95%. Helical CT’s advantages come at a higher cost compared to an IVP. CASE ONE CONTINUED: After confirming that the patient has a stone (3.5mm in the distal portion of the right ureter, with no hydronephrosis) you send him home with NSAIDs, a strainer, and a recommendation to drink lots of fluids. 3. Describe your approach in working up the cause of kidney stones after the first presentation. Describe any additional evaluation you would do in a recurrent stone former. First, review the patient’s history for risk factors that might predispose him to stone formation: e.g. his race and occupation (e.g. truck driver); HTN on a diuretic (esp. furosemide, ethacrynic acid); and antacids to treat his reflux sxs, which can change the urine pH, and make it more alkaline. Some other risk factors to consider include: Intestinal disease—such as Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis, chronic diarrhea, leukemia/lymphoma, chemotherapy, thyroid meds, large doses of vitamin C, prior urinary or bladder infections, blood relatives with kidney stones (45% of calcium stone formers have a genetic basis), gout or family history of gout, sarcoidosis, or parathyroid problems. Patients with AIDS on a medication combination, which includes indinavir, zidovudine, or lamivudine have >35% risk for kidney stones. Patients with stones less than 4mm should pass their stone in 1-2 weeks and generally, require no intervention other than analgesia. The fact that this patient’s stone is in the distal ureter is a good sign. An imaging study should be performed within the first 2 weeks to confirm the stone has completely passed. If the stone has not passed or is large (>5mm) the patient needs referral to the urologist. The recurrence rate for patients who pass a calcium stone is about 50% by ten years. However, since the course of most stones is quite indolent, most recommend a limited work-up after the first calcium stone and dietary/lifestyle modifications that would be recommended independent of a stone (e.g. maintain good hydration, limit excessive red meat consumption). One approach to “first stones” is to check a serum calcium in patients with radio-opaque stones and a serum uric acid in those with radiolucent stones. Patients with recurrent stones require a more detailed metabolic work-up. This would include: serum electrolytes, BUN, creatinine, calcium to screen for hypercalcemia (hyperparathyroidism, most common in women with calcium stones, or malignancy), uric acid to screen for hyperuricemia , magnesium, phosphate, a cbc, lfts, pregnancy test if female. Obtain two 24-hour urine collections with Mr. Stone on a normal diet and fluid intake while stopping his thiazide diuretic. The urine should be checked for volume, calcium, uric acid, citrate, oxalate, creatinine, pH, and sodium. Measurement of 24-hour urinary sodium excretion is important. One can achieve low urinary calcium and uric acid levels, and fewer stones, either through volume depletion or a low sodium diet. Elevated urinary sodium suggests that the patient should ensure adequate volume and ensure a low sodium diet. Normal values for 24-hour urinary excretion Calcium Uric Acid Citrate Oxalate Creatinine Men <300 mg <800 mg 450-600 mg <45 mg 20-45 mg/Kg Women <250 mg <750 mg 650-800 mg <45 mg 5-20 mg/Kg Hypercalciuria is the most common cause of calcium stones and is felt to be due to an increased GI absorption in patients with recurrent stones. Can check a 1,25 OH vit D level. Hypocitriuria is another major contributor to calcium stones. Calcium phosphate stones are most likely due to renal tubular acidosis. Patients with non-calcium stones usually have identifiable metabolic disorder. 4. If the patient were 55 years old with a calcium stone and taking calcium supplements “for her bones” would you tell her to stop? Not necessarily. It has been fairly well established that dietary calcium is protective against calcium oxalate stones (dietary calcium binds oxalate). Therefore, we would like her to get more of her daily calcium from dietary sources (perhaps, a bowl of Total each morning). In one study, women who took calcium supplements had a 20% higher risk for stones. This may be because the supplements were taken without food, which resulted in less binding of oxalate and more oxalate in the urine. So, she can continue to take calcium supplements (up to 1200 mg/day) with food or simply make an effort to meet those requirements with more dietary calcium. References: 1. Parmar, M.S. Kidney stones. BMJ. 2004; 328:1420-1424. Additional References: 1. Portis, Andrew J, M.D., and Sundaram, Chandru P., M.D. Diagnosis and initial management of kidney stones. American Family Physician. 2001; Vol.63, Num.7:1329-1338. 2. Goldfarb, David, M.D. et al. Prevention of recurrent nephrolithiasis. American Family Physician. 1999. 60:2269-2276.