lis 512: introduction to knowledge organization

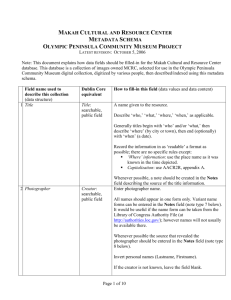

advertisement

SUBJECT ANALYSIS AND SUBJECT CATALOGING WHAT IS SUBJECT CATALOGING? Once a cataloger completes the description of an information package and determines the appropriate nonsubject or "name" access points, her/his task now becomes one of how to relate the materials intellectually to one another in a particular retrieval tool and, [possibly] at the same time, relate the materials physically by way of some type of shelf arrangement. S/he must assign subject access points—subject headings and call numbers—by completing the subject cataloging step or what Bohdan Wynar refers to as determining the "aboutness" of a work. Subject headings and call numbers provide different but complementary modes of access and the activities providing for their assignment go hand in hand. For those information packages for which the surrogate/metadata record will ultimately be part of a [library] catalogue/database the activities are (1) subject heading work and (2) classification. Subject analysis goes somewhat beyond subject cataloguing to include determining the "aboutness" of documents for which the surrogate record may appear elsewhere than in a library catalogue/database—in an abstracting and indexing tool, for example. Abstracting may be defined as the process of preparing an abbreviated, accurate representation (or synopsis) of the work, usually without added interpretation or criticism. Indexing is the process of providing a systematic guide to the contents of a document by way of an ordered arrangement of terms, symbols, etc. representing the contents. WHAT ARE THE COMPONENT ACTIVITIES OF SUBJECT CATALOGUING? (1) Subject Heading Work (a) assigning subject headings (b) making cross-references (creating a syndetic structure) alphabetical, verbal approach words or phrases one, or many, or none ... what about fiction or other works of literature? (2) Classification (a) assigning class numbers (b) completing call numbers (or what LC calls shelflisting) systematic approach code, notation, symbol (e.g., 398.2 CLE, 025.3'16 H145, Z699.35 M28H34, ...) only one ... WHAT ARE THE STEPS IN THE SUBJECT CATALOGUING PROCESS? Taylor refers to this sequence of steps more generally as the subject analysis process; she is focussing on the broader context, but she and I are talking about the same thing. We are talking about what Chan has characterized as one of the most difficult challenges a librarian faces— figuring out what something (an information package or a request from a client) is all "about". 1. Determine the general subject Taylor refers to this step and the one following as "conceptual analysis," i.e., the determination of what the intellectual content of an item is "about" and/or the determination of what the item "is". In other words, you want to determine the general subject content of the information package unless its form or genre takes precedence as is the case with, for example, literature, music, and general works such as encyclopedias, dictionaries, and the like. For bibliographies and biographies, either topical content or form may take precedence depending on your local policies [which, in turn, may be based on personal preference and/or whatever is most practical in a given context]. (This is my rule of the "3 Ps".) Even in cases where form or genre does not take precedence, it is very useful to note [in your subject analysis] if an information package is presented in a particular form or format. Taylor offers some excellent advice (pp. 317-320) on what some cataloguers and indexers refer to as "reading the work technically". She tells you what to look for and what pitfalls to avoid when examining information packages that contain text as well as those that contain nontextual information. This initial conceptual analysis enables you to compose a general subject statement such as, "This book is about sociology," for an information package titled An Introduction to Sociology or History of Sociology, for example. 2. Identify the emphasis/focus—aspect(s) of subject stressed In this step you will [if necessary and appropriate] expand your general subject statement using clear, unambiguous subject terms—terms that name concept(s) as concisely, specifically, and directly as possible. For example: "This book is about sociology from a historical perspective. It covers the development of the discipline from its origins to the mid-twentieth century. It is written by an expert in the field—a professor at a prestigious American university—and it is intended for an academic audience at the graduate student level at least." Taylor states on p. 306: "Determining what an information package is about can be difficult." 3. Fit these terms into a standard list/source Taylor refers to this step as "translating" the conceptual analysis into the conceptual framework of the classification or controlled vocabulary system being used by the cataloguer, indexer, or classifier". Such systems/sources are, of course, examples of authority files available in a variety of formats—print, microform, "online", and CD-ROM, to name a few. The major controlled vocabulary with which a cataloguer must be familiar is that in a standard list of subject headings such as LCSH—the "big red books." There is excellent detail in Taylor chapter 10 on systems for vocabulary control. 4. Verify term(s), notations in a standard list/source Following these conceptual steps, Taylor advises you that the framework must be translated into the specific classificatory symbols or specific terminology used in the classification or controlled vocabulary system, i.e., pick your number or pick your subject term(s). 5. Verify usage of term(s), notations in own catalogue/database This step ensures that the subject heading(s) or notation assigned in completing the process of subject analysis are not only correct for the content of the item and in the correct context, as complete as they can/need to be, but also consistent with past usage in your catalogue. (This is my rule of the "4 Cs".) Yeah, so …? To put all of this into perspective, recall that one of the secondary goals of this class was to make you more efficient reference and information librarians. It is not likely that many of you will actually go through the steps in the subject analysis process as a cataloger, i.e., dealing with the item in hand and analyzing it for its subject content, because few of you will do "original" cataloging. What is much more likely is that you will be attempting to match that subject content to a patron's request—determining which subject terms the cataloger has used. You will frequently ask yourself: How can I "translate" the natural language of the patron into the controlled vocabulary of a standard list of subject headings and the notations from a classification scheme [used for shelf arrangement]? To do this well you need to know how controlled vocabularies are structured and developed, and applied … or not applied as the case may be, and therefore when it is wise to conduct a keyword search or a keyword search in combination with controlled vocabulary. What types of subject headings are there? Taylor takes a slightly different perspective here answering the question by stating that different types of concepts—topics, names (including persons, corporate bodies, geographic areas, etc.), time periods, and forms—can be used as subjects of information packages. 1. Names persons (600) places (651) corporate bodies (610, 611) uniform titles (630) formatted via AACR2R—chapters 22, 23, 24 NOT in LCSH except as examples and/or in "pattern" headings in own name authority files also name.[uniform] title (600 [or 610] with title portion in subfield $t) Taylor addresses "Names Used As Subject Concepts" on pages 321-322. 2. Single Nouns topical subject headings (650) for things/objects, actions, concepts simplest, fewest problems but problems may arise with ... - singular vs. plural (concepts vs. objects) - homographs sometimes a single noun won't always do ... 3. Modified (expanded or qualified) Nouns noun + qualifier in parentheses, e.g., .... adjective(s) + noun(s), e.g., ... noun, adjective, e.g., ... where to look? (inverted headings are disappearing in LCSH—they have disappeared completely in Sears—except for those modified by ethnic group, nationality, language, broad time period) - so, Foreign investments but Art, Medieval 4. Phrases (a) Conjunctive Phrases compounds, opposites, interactions; e.g., ... (b) Prepositional Phrases use as, for, in, of, etc.; e.g., ... 5. Subjects with Subdivisions means of subject specification limit scope of main subject provide means of subarrangement main heading can be any of above not always there even when expected ...? "dashed on" subdivisions of various types, for example ... (a) Topical Subdivisions ($x in MARC 6XX) contrary to specific, direct principle? bring out aspects, facets of subjects not genus-species, whole-parts relationships often subject headings in their own right find in Free-Floating Subdivisions apply "judiciously" to or to specified groups of headings (b) Form Subdivisions ($x in older records but $v now [as of February 1999]) Encyclopedias, Dictionaries, etc. (c) Geographic Subdivisions ($z in MARC 6XX) only when instructed but note where instruction falls [in older records]—after main heading (as above) or after subdivision, e.g., Libraries—Censorship—Canada current move to put last, or at least be consistent indirect vs. direct direct for provinces in Canada, states in the US, constituent countries in the UK, and constituent republics in the "old" USSR, e.g., Flags--New York all others indirect including locales "below" provincial, state, etc. level in Canada, the US, the UK, and the USSR, e.g., Flags--New York (State)--New York; Flags--Brazil; Flags--France-Paris where to start? topic or place? - topic for scientific, technological, economic, educational, artistic; e.g., ... - place for history, description, administration, social subjects; e.g., ... (d) Chronological Subdivisions ($y in MARC 6XX) mostly for history, literature, art; e.g., ... Taylor addresses "Chronological Elements As Subject Concepts" on pages 322. Note that she does not restrict time elements to subdivision status only—named periods and styles, for example, may be treated as topical subject headings in their own right.